Accurate identification of paediatric patients with severe asthma is essential for an adequate management of the disease. However, criteria for defining severe asthma and recommendations for control vary among different guidelines.

Material and methodsAn online survey was conducted to explore expert opinions about the definition and management of severe paediatric asthma. To reach a consensus agreement, a modified Delphi technique was used, and practice guidelines were prepared after the analysis of the results.

ResultsEleven paediatric pulmonologists and allergists with wide expertise in severe asthma responded to the survey. Consensus was reached in 50 out of 65 questions (76.92%). It was considered that a patient has severe asthma if during the previous year they had required 2 or more cycles of oral steroids, required daily treatment with medium doses of inhaled corticosteroids (with other controller medication) or high doses (with or without other controller medication), did not respond to optimised conventional treatment, or if the disease threatened the life of the patient or seriously impaired their quality of life. The definition of severe asthma may also include patients who justifiably use health resources on a regular basis, or have psychosocial or environmental factors impeding control. For monitoring, the use of questionnaires designed specifically for paediatric population, such as CAN or ACT, is recommended. As regards treatment, the use of omalizumab should be considered prior to the use of oral corticosteroids.

ConclusionsThis paper provides consensus recommendations that may be useful in the management of severe paediatric asthma.

La identificación adecuada del paciente pediátrico con asma grave es esencial para su correcto manejo. Sin embargo, los criterios para definir el asma grave y las recomendaciones para su control varían mucho entre las distintas guías.

Material y métodosSe elaboró una encuesta telemática para analizar las opiniones relativas a la definición y control del asma grave pediátrica. Para lograr un consenso se siguió una metodología Delphi modificada. Con los resultados se elaboraron recomendaciones prácticas.

ResultadosEl cuestionario fue respondido por 11 neumólogos y alergólogos pediátricos expertos en asma grave. Hubo consenso en 50 de los 65 ítems planteados (76,92%). Se consideró que un paciente tiene asma grave si en el último año ha requerido 2 o más ciclos de corticoides orales, si requiere tratamiento diario con corticoides inhalados a dosis medias (con otra medicación controladora) o dosis altas (con o sin otra medicación controladora), si no responde a un tratamiento convencional optimizado, o si la enfermedad pone en riesgo su vida o deteriora gravemente su calidad de vida. La definición de asma grave también podría incluir a los pacientes que consumen recursos sanitarios de manera regular y justificada, o tienen factores psicosociales o ambientales que impiden su control. Para la monitorización, se recomienda usar cuestionarios específicos de población pediátrica (CAN o ACT). Respecto al tratamiento, se debería considerar el uso de omalizumab en un escalón anterior al de los corticoides orales.

ConclusionesEl presente trabajo ofrece recomendaciones consensuadas que pueden ser de utilidad en el manejo del asma grave pediátrica.

Asthma is one of the most frequent chronic diseases.1–3 In Spain, its prevalence ranges between 7.1% and 12.9% in children aged 6–7 years, and between 7.1% and 15.3% in those aged 13–14 years.3 Studies conducted outside of Spain have estimated a prevalence of paediatric asthma of 2.5%.4,5 Despite advances in treatment, severe asthma continues to be associated to high rates of morbidity6 and to a mortality rate that, despite a decrease in recent years, continues to be significant.7 Furthermore, asthma generates high direct and indirect costs,8 with severe asthmatic patients consuming most of the resources allocated to this disease.1,8

Severity is an intrinsic characteristic of asthma that reflects the intensity of the pathophysiological abnormalities, encompassing both the intensity of the disease process and the response to treatment.9 We ought to differentiate between the concepts of severity and control. Control is the degree to which therapeutic interventions minimise or lead to the absence of asthma symptoms and the goals of therapy are met while reducing the risk of exacerbations and medication side effects.1,9,10 The correct identification of patients with severe asthma is essential to the appropriate management of the disease, mainly because the treatment and followup of patients depend on it.9,11 Similarly, a correct assessment of control is needed to adjust the treatment.9 However, the recommendations for the definition of severe asthma and for assessing control are inconsistent across guidelines.1,9–12

In response to the disparate criteria that affect the assessment of asthma severity and control, we developed a project in order to learn the perspective on these aspects from paediatric pulmonologists and paediatric allergists with expertise in the management of severe asthma. Our goal was not to create new definitions of severity and control, but to unify the criteria used in the diagnosis of severe asthma in clinical practice and specify the measures required for the correct followup of these patients. Furthermore, we developed consensus recommendations for the appropriate referral of children with severe asthma to specialised or tertiary care, and for the management of patients according to disease severity, including the use of novel therapies, particularly of recently introduced biological agents.13

Materials and methodsStudy designTo reach an expert consensus, we used a modified Delphi method following the recommendations of the RAND/UCLA.14,15 We carried out the following steps:

- 1.

Literature review, face-to-face discussion, and development of a questionnaire consisting of a series of statements, all performed by a scientific committee.

- 2.

Selection of a panel of experts by the scientific committee.

- 3.

Distribution to the panel of experts of an online questionnaire in two rounds.

- 4.

Analysis of results and preparing the document.

The scientific committee performed a literature review by searching for clinical practice guidelines and literature reviews on the subject of severe asthma in the following databases: Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library, U.S. National Guidelines Clearinghouse, Tripdatabase and GuíaSalud. The search was conducted in April 2014 and restricted to studies published in Spanish and English in the past five years.

Development and evaluation of the questionnaireFollowing the literature review, the scientific committee developed a questionnaire with items addressing controversial aspects related to severe asthma. The items were evaluated online on a nine-point Likert scale (1=completely disagree; 9=completely agree). The responses were grouped into three regions (1–3=disagreement; 4–6=neither agreement nor disagreement; 7–9=agreement). All items for which the panel did not reach a consensus during the first round were reevaluated in a second round. Between rounds, panellists were informed in detail of the distribution of responses in the first round.

Analysis of resultsWe considered that consensus had been reached on an item if the median score was in the 7–9 region (consensus in agreement) or in the 1–3 region (consensus in disagreement). Furthermore, our definition of consensus required that the number of panellists voting outside the 1–3 or 7–9 region be less than one third of the total, and that the interquartile range (IQR) be four or less. We present the results in tables reporting the median score, IQR, level of agreement between panellists and final result of the consensus for each item (consensus in agreement or disagreement in the first or second round, or no consensus). The level of agreement denotes the percentage of panellists that scored the item in the range containing the median score (1–3, 4–6 or 7–9). In order to simplify the results, we developed a list of ten main recommendations based on the most relevant items on which a consensus had been reached, and the list was reviewed and approved by the entire panel of experts.

ResultsEleven paediatric pulmonologists and allergists with expertise in paediatric asthma from seven autonomous communities in Spain responded to the survey. The questionnaire consisted of 65 items divided into four sections (Tables 1–4).

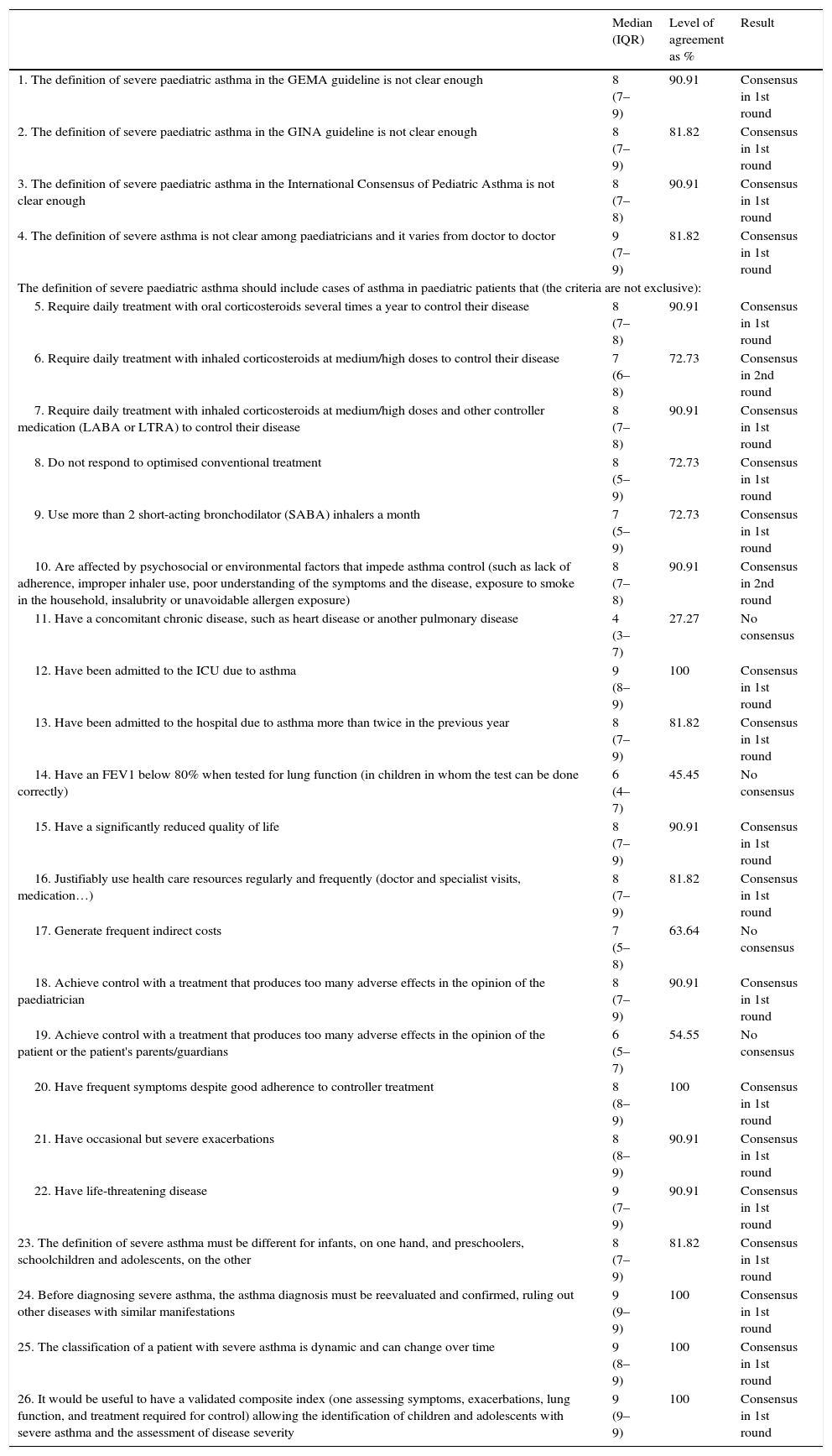

Results of Section I: definition of severe paediatric asthma.

| Median (IQR) | Level of agreement as % | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The definition of severe paediatric asthma in the GEMA guideline is not clear enough | 8 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 2. The definition of severe paediatric asthma in the GINA guideline is not clear enough | 8 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 3. The definition of severe paediatric asthma in the International Consensus of Pediatric Asthma is not clear enough | 8 (7–8) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 4. The definition of severe asthma is not clear among paediatricians and it varies from doctor to doctor | 9 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| The definition of severe paediatric asthma should include cases of asthma in paediatric patients that (the criteria are not exclusive): | |||

| 5. Require daily treatment with oral corticosteroids several times a year to control their disease | 8 (7–8) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 6. Require daily treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at medium/high doses to control their disease | 7 (6–8) | 72.73 | Consensus in 2nd round |

| 7. Require daily treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at medium/high doses and other controller medication (LABA or LTRA) to control their disease | 8 (7–8) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 8. Do not respond to optimised conventional treatment | 8 (5–9) | 72.73 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 9. Use more than 2 short-acting bronchodilator (SABA) inhalers a month | 7 (5–9) | 72.73 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 10. Are affected by psychosocial or environmental factors that impede asthma control (such as lack of adherence, improper inhaler use, poor understanding of the symptoms and the disease, exposure to smoke in the household, insalubrity or unavoidable allergen exposure) | 8 (7–8) | 90.91 | Consensus in 2nd round |

| 11. Have a concomitant chronic disease, such as heart disease or another pulmonary disease | 4 (3–7) | 27.27 | No consensus |

| 12. Have been admitted to the ICU due to asthma | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 13. Have been admitted to the hospital due to asthma more than twice in the previous year | 8 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 14. Have an FEV1 below 80% when tested for lung function (in children in whom the test can be done correctly) | 6 (4–7) | 45.45 | No consensus |

| 15. Have a significantly reduced quality of life | 8 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 16. Justifiably use health care resources regularly and frequently (doctor and specialist visits, medication…) | 8 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 17. Generate frequent indirect costs | 7 (5–8) | 63.64 | No consensus |

| 18. Achieve control with a treatment that produces too many adverse effects in the opinion of the paediatrician | 8 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 19. Achieve control with a treatment that produces too many adverse effects in the opinion of the patient or the patient's parents/guardians | 6 (5–7) | 54.55 | No consensus |

| 20. Have frequent symptoms despite good adherence to controller treatment | 8 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 21. Have occasional but severe exacerbations | 8 (8–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 22. Have life-threatening disease | 9 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 23. The definition of severe asthma must be different for infants, on one hand, and preschoolers, schoolchildren and adolescents, on the other | 8 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 24. Before diagnosing severe asthma, the asthma diagnosis must be reevaluated and confirmed, ruling out other diseases with similar manifestations | 9 (9–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 25. The classification of a patient with severe asthma is dynamic and can change over time | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 26. It would be useful to have a validated composite index (one assessing symptoms, exacerbations, lung function, and treatment required for control) allowing the identification of children and adolescents with severe asthma and the assessment of disease severity | 9 (9–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

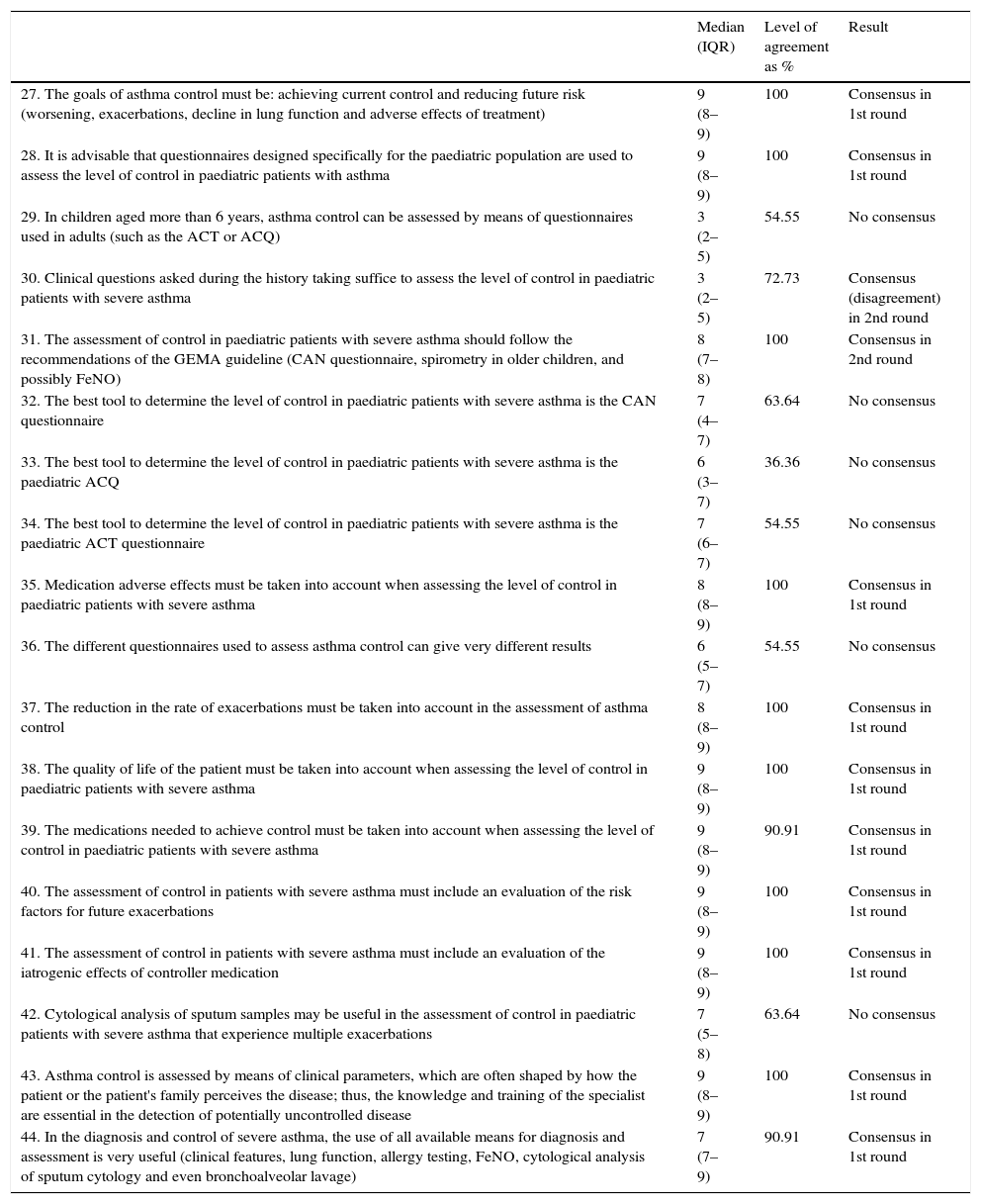

Results of Section II: monitoring control in severe paediatric asthma.

| Median (IQR) | Level of agreement as % | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27. The goals of asthma control must be: achieving current control and reducing future risk (worsening, exacerbations, decline in lung function and adverse effects of treatment) | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 28. It is advisable that questionnaires designed specifically for the paediatric population are used to assess the level of control in paediatric patients with asthma | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 29. In children aged more than 6 years, asthma control can be assessed by means of questionnaires used in adults (such as the ACT or ACQ) | 3 (2–5) | 54.55 | No consensus |

| 30. Clinical questions asked during the history taking suffice to assess the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma | 3 (2–5) | 72.73 | Consensus (disagreement) in 2nd round |

| 31. The assessment of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma should follow the recommendations of the GEMA guideline (CAN questionnaire, spirometry in older children, and possibly FeNO) | 8 (7–8) | 100 | Consensus in 2nd round |

| 32. The best tool to determine the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma is the CAN questionnaire | 7 (4–7) | 63.64 | No consensus |

| 33. The best tool to determine the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma is the paediatric ACQ | 6 (3–7) | 36.36 | No consensus |

| 34. The best tool to determine the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma is the paediatric ACT questionnaire | 7 (6–7) | 54.55 | No consensus |

| 35. Medication adverse effects must be taken into account when assessing the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma | 8 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 36. The different questionnaires used to assess asthma control can give very different results | 6 (5–7) | 54.55 | No consensus |

| 37. The reduction in the rate of exacerbations must be taken into account in the assessment of asthma control | 8 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 38. The quality of life of the patient must be taken into account when assessing the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 39. The medications needed to achieve control must be taken into account when assessing the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma | 9 (8–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 40. The assessment of control in patients with severe asthma must include an evaluation of the risk factors for future exacerbations | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 41. The assessment of control in patients with severe asthma must include an evaluation of the iatrogenic effects of controller medication | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 42. Cytological analysis of sputum samples may be useful in the assessment of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma that experience multiple exacerbations | 7 (5–8) | 63.64 | No consensus |

| 43. Asthma control is assessed by means of clinical parameters, which are often shaped by how the patient or the patient's family perceives the disease; thus, the knowledge and training of the specialist are essential in the detection of potentially uncontrolled disease | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 44. In the diagnosis and control of severe asthma, the use of all available means for diagnosis and assessment is very useful (clinical features, lung function, allergy testing, FeNO, cytological analysis of sputum cytology and even bronchoalveolar lavage) | 7 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

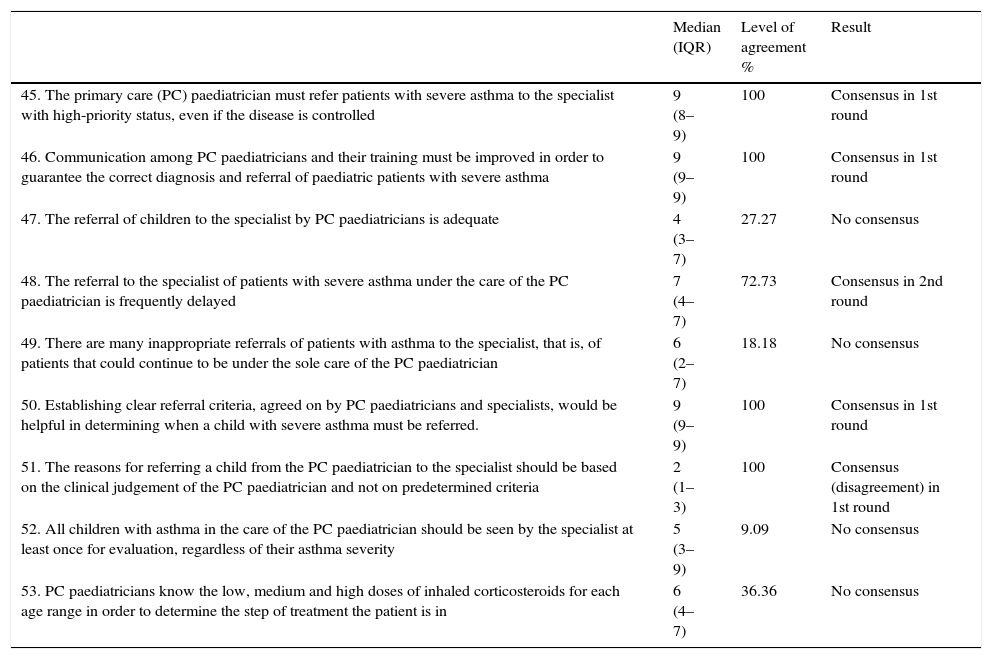

Results of Section III: referral of patients with severe asthma.

| Median (IQR) | Level of agreement % | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45. The primary care (PC) paediatrician must refer patients with severe asthma to the specialist with high-priority status, even if the disease is controlled | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 46. Communication among PC paediatricians and their training must be improved in order to guarantee the correct diagnosis and referral of paediatric patients with severe asthma | 9 (9–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 47. The referral of children to the specialist by PC paediatricians is adequate | 4 (3–7) | 27.27 | No consensus |

| 48. The referral to the specialist of patients with severe asthma under the care of the PC paediatrician is frequently delayed | 7 (4–7) | 72.73 | Consensus in 2nd round |

| 49. There are many inappropriate referrals of patients with asthma to the specialist, that is, of patients that could continue to be under the sole care of the PC paediatrician | 6 (2–7) | 18.18 | No consensus |

| 50. Establishing clear referral criteria, agreed on by PC paediatricians and specialists, would be helpful in determining when a child with severe asthma must be referred. | 9 (9–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 51. The reasons for referring a child from the PC paediatrician to the specialist should be based on the clinical judgement of the PC paediatrician and not on predetermined criteria | 2 (1–3) | 100 | Consensus (disagreement) in 1st round |

| 52. All children with asthma in the care of the PC paediatrician should be seen by the specialist at least once for evaluation, regardless of their asthma severity | 5 (3–9) | 9.09 | No consensus |

| 53. PC paediatricians know the low, medium and high doses of inhaled corticosteroids for each age range in order to determine the step of treatment the patient is in | 6 (4–7) | 36.36 | No consensus |

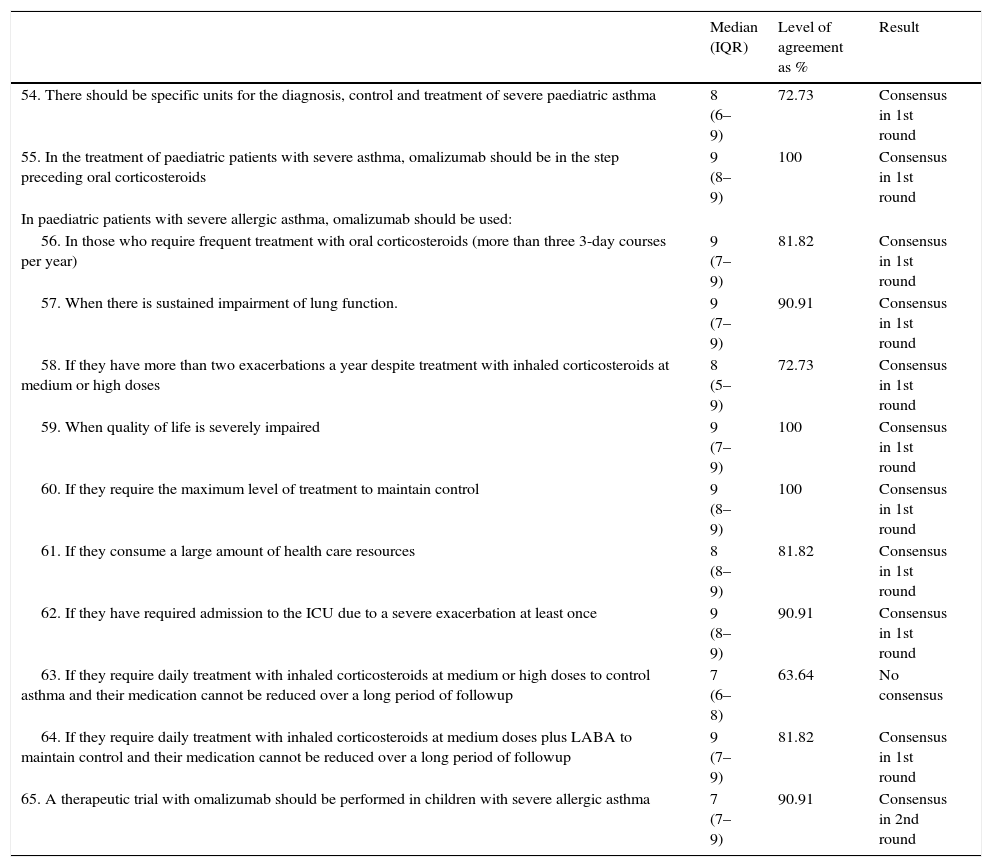

Results of Section IV: Therapeutic approach for severe paediatric asthma.

| Median (IQR) | Level of agreement as % | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 54. There should be specific units for the diagnosis, control and treatment of severe paediatric asthma | 8 (6–9) | 72.73 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 55. In the treatment of paediatric patients with severe asthma, omalizumab should be in the step preceding oral corticosteroids | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| In paediatric patients with severe allergic asthma, omalizumab should be used: | |||

| 56. In those who require frequent treatment with oral corticosteroids (more than three 3-day courses per year) | 9 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 57. When there is sustained impairment of lung function. | 9 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 58. If they have more than two exacerbations a year despite treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at medium or high doses | 8 (5–9) | 72.73 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 59. When quality of life is severely impaired | 9 (7–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 60. If they require the maximum level of treatment to maintain control | 9 (8–9) | 100 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 61. If they consume a large amount of health care resources | 8 (8–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 62. If they have required admission to the ICU due to a severe exacerbation at least once | 9 (8–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 63. If they require daily treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at medium or high doses to control asthma and their medication cannot be reduced over a long period of followup | 7 (6–8) | 63.64 | No consensus |

| 64. If they require daily treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at medium doses plus LABA to maintain control and their medication cannot be reduced over a long period of followup | 9 (7–9) | 81.82 | Consensus in 1st round |

| 65. A therapeutic trial with omalizumab should be performed in children with severe allergic asthma | 7 (7–9) | 90.91 | Consensus in 2nd round |

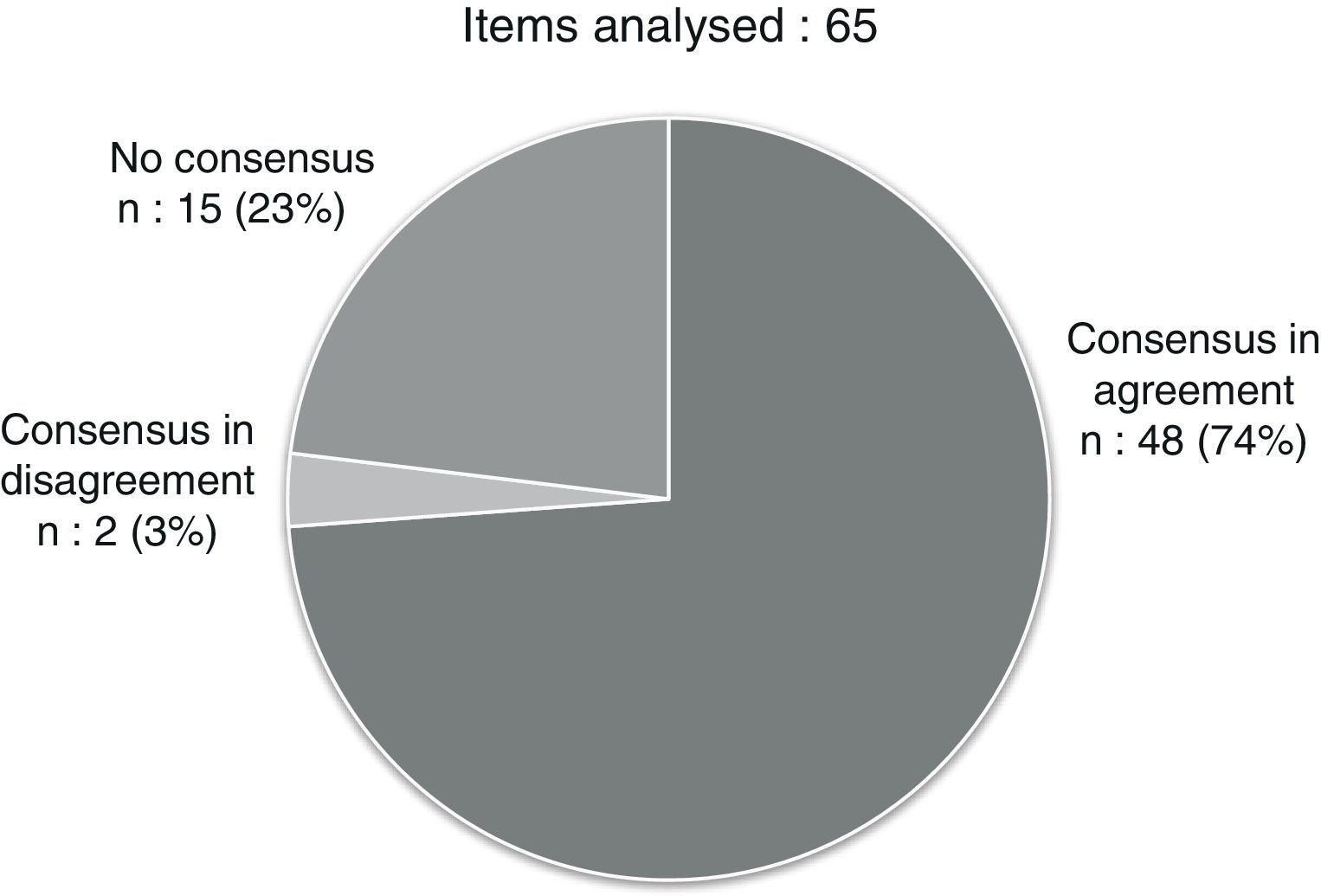

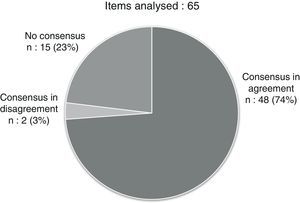

The first section addressed the definition of severe paediatric asthma. Consensus in agreement was reached for 22 out of the 26 proposed items (84.6%). The second section addressed the monitoring of control in severe paediatric asthma, with consensus reached for 12 of the 18 items (66.6%): 11 in agreement and one in disagreement. Sections III and IV dealt with the referral of and therapeutic approach to children with severe asthma. A consensus was reached for 5 of the 9 items in section III (55.5%, 4 in agreement and 1 in disagreement), and for 11 of the 12 items in section IV (91.6%).

After the two evaluation rounds, a consensus had been reached for 50 out of the 60 items in the questionnaire (76.92%): 48 in agreement and 2 in disagreement (Fig. 1 and Tables 1–4). We summarised the most relevant items for which a consensus was reached into 10 recommendations (Table 5).

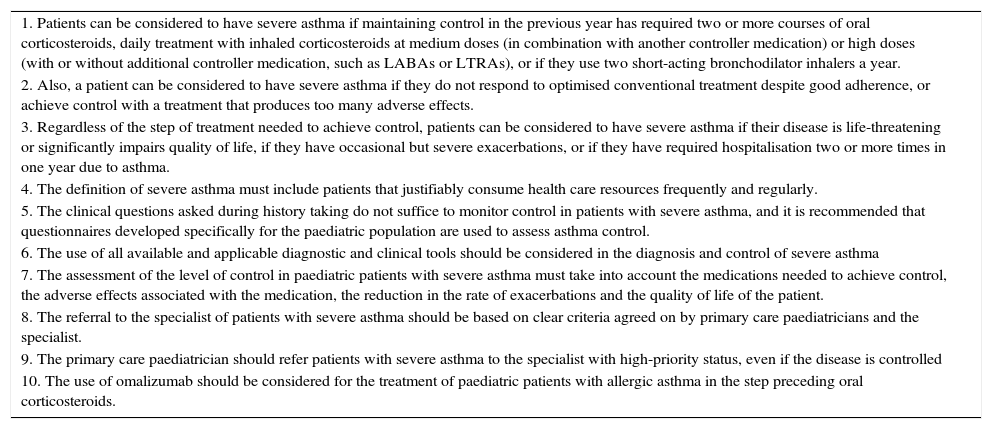

The 10 recommendations for the management of children with severe asthma.

| 1. Patients can be considered to have severe asthma if maintaining control in the previous year has required two or more courses of oral corticosteroids, daily treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at medium doses (in combination with another controller medication) or high doses (with or without additional controller medication, such as LABAs or LTRAs), or if they use two short-acting bronchodilator inhalers a year. |

| 2. Also, a patient can be considered to have severe asthma if they do not respond to optimised conventional treatment despite good adherence, or achieve control with a treatment that produces too many adverse effects. |

| 3. Regardless of the step of treatment needed to achieve control, patients can be considered to have severe asthma if their disease is life-threatening or significantly impairs quality of life, if they have occasional but severe exacerbations, or if they have required hospitalisation two or more times in one year due to asthma. |

| 4. The definition of severe asthma must include patients that justifiably consume health care resources frequently and regularly. |

| 5. The clinical questions asked during history taking do not suffice to monitor control in patients with severe asthma, and it is recommended that questionnaires developed specifically for the paediatric population are used to assess asthma control. |

| 6. The use of all available and applicable diagnostic and clinical tools should be considered in the diagnosis and control of severe asthma |

| 7. The assessment of the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma must take into account the medications needed to achieve control, the adverse effects associated with the medication, the reduction in the rate of exacerbations and the quality of life of the patient. |

| 8. The referral to the specialist of patients with severe asthma should be based on clear criteria agreed on by primary care paediatricians and the specialist. |

| 9. The primary care paediatrician should refer patients with severe asthma to the specialist with high-priority status, even if the disease is controlled |

| 10. The use of omalizumab should be considered for the treatment of paediatric patients with allergic asthma in the step preceding oral corticosteroids. |

This document attempts to provide a practical and consensus-based perspective on severe paediatric asthma with emphasis on its definition and level of control, as well as patient referral and optimal management. The first three items of the questionnaire showed that the definition of severe paediatric asthma is not sufficiently clear in various guidelines, such as the Guía Española de Manejo del Asma (Spanish Guideline for the Management of Asthma [GEMA]),9 the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) guidelines,1 or the International Consensus on Pediatric Asthma (ICON) guidelines for the paediatric population.10 Indeed, the definitions for asthma and for severity and control are not only inconsistent across these three guidelines, but also in relation to the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society (ERS/ATS)12 and the World Health Organization guidelines.11 Most guidelines agree that severity of disease ought to be determined mainly on the basis of the step of treatment the patient requires to maintain control. However, their definitions of severity and control and the steps of treatment are not uniform. This inconsistency is probably the reason why the panel of experts agreed on considering that there is no clear definition of severe asthma and that the term is applied according to the judgement of each individual physician, as indicated by item 4 in the questionnaire.

In this regard, we must take into account that the assessment of severe asthma is different in infants, on one hand, and preschoolers, schoolchildren and adolescents, on the other. Thus, the asthma diagnosis must be reevaluated and confirmed before diagnosing severe asthma, ruling out other diseases with similar manifestations and keeping in mind that the classification of a patient with asthma is dynamic and can change over time.

The items that followed (5–22) sought a consensus on the elements that must be included in the definition of severe paediatric asthma. The agreement reached on this subject was that asthma should be considered severe in patients in whom one of the following occurs in the context of asthma control: having required two or more courses of oral corticosteroids in the previous year; requiring daily treatment with medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids combined with other controller medication, or requiring daily treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids with or without additional controller medication, such as long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) or leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs); or using one short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) inhaler per month. In their comments regarding the questionnaire, some panellists stated that the use of as few as two SABA inhalers per year should be considered severe asthma, in adherence with current guidelines,16,17 as SABA use could be indicative of uncontrolled disease. The inclusion of inhaled corticosteroids at medium doses as monotherapy (consensus reached in the second round) and the consideration of SABA use are not criteria applied to the definition of severe asthma in the ICON, GINA or GEMA guidelines. However, the panellists expressed that in everyday clinical practice, these patients are usually considered to have severe disease.

In addition to determining severity by means of the step of treatment required for control, the panel reached a consensus on other clinical situations that may be considered severe in everyday clinical practice and that mainly pertain to the intrinsic severity of the disease. In this sense, a patient is considered to have severe asthma in the following cases: if the disease is life-threatening or significantly impairs quality of life; if exacerbations are occasional but severe, leading to hospitalisation and threatening the life of the patient; or if the patient has been hospitalised twice or more due to asthma in the previous year. A recently published document12 even considered a single admission to the ICU or to the hospital sufficient to categorise asthma as severe. Along the same lines, the panel also defined severe asthma as the patient not responding to optimised conventional treatment despite its correct implementation; the patient achieving adequate asthma control, but with a treatment that causes too many adverse effects in the opinion of the paediatrician; or the patient experiencing frequent symptoms despite good adherence to maintenance treatment. Furthermore, to complete the spectrum of clinical situations indicative of severe asthma, the panel reached a consensus in the second round regarding factors extrinsic to the disease, including factors pertaining to the patient or to the patient's social environment. Thus, the panel considered that the definition of severe asthma may also include patients that justifiably use health care resources frequently and regularly, or whose asthma worsens due to psychosocial or environmental factors that impede its control (for instance, non-adherence to treatment, improper inhaler use, poor understanding of the symptoms or the disease, exposure to smoke in the household, insalubrity, or unavoidable exposure to allergens), that is, with severe asthma that is difficult to control. All these clinical scenarios may guide the paediatrician in identifying patients with severe asthma in order to adjust their management accordingly. The panel also considered that it would be useful to have a validated composite index (one assessing symptoms, exacerbations, lung function and treatment needed for control) allowing the identification of children and adolescents with severe asthma and the assessment of disease severity. This recommendation is consistent with the high number of clinical situations that have been considered definitions of severe asthma in this section.

When it comes to the items in Section I for which a consensus was not reached, we want to highlight the exclusion from the definition of severe asthma of cases in which the isolated finding, in the absence of any other objective evidence of severity, is a decline in lung function with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of less than 80%, despite it being a parameter included in many guidelines. Furthermore, we consider that a FEV1 of more than 80% does not rule out the presence of severe asthma.

Section II dealt with the monitoring of severe paediatric asthma. We ought to note that, consistent with the recommendations of the GEMA and GINA guidelines, the panel agreed that in addition to pursuing current control, monitoring should include the assessment and reduction of future asthma-related risk (worsening, exacerbations, decline in pulmonary function and adverse effects of treatment). To monitor these aspects, we recommend the use of questionnaires specifically designed for the paediatric population, and believe that clinical questions asked during the history taking do not suffice to assess control in paediatric patients with severe asthma. However, no consensus was reached as to which questionnaire ought to be used. When panellists were asked specifically which tool is best for assessing the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma, there was no consensus in choosing between the paediatric Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ACQ), the paediatric Asthma Control Test (ACT) or the Control del Asma en Niños (Asthma Control in Children [CAN]), although a consensus was almost reached in favour of the latter.

Since there was no specific answer, in the second round the panellists agreed to accept that the level of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma should be assessed following the recommendations of the GEMA guidelines (CAN questionnaire, spirometry in older children, and possibly FeNO in other patients).9 The panel also considered that it would be best to exhaust all diagnostic and evaluation possibilities for the diagnosis and control of severe asthma (clinical assessment, lung function testing, allergy testing, FeNO, cytological analysis of sputum or even bronchoalveolar lavage). However, no consensus was reached when the survey asked specifically about the use of cytological analysis of sputum samples in the assessment of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma that have multiple exacerbations, which would be consistent with other guidelines, such as the ERS/ATS,12 that also do not recommend its generalised use. For the purposes of clinical practise and in summary, the panellists considered that the assessment of control in paediatric patients with severe asthma should take into account the medication needed to achieve control, the adverse effects associated with the medication, the reduction in the rate of exacerbations and the quality of life of the patient. Finally, it is worth noting that the panel considered that the training of the specialist is key in the detection of uncontrolled disease, as monitoring is essentially conducted on the basis of clinical parameters that are often influenced by how the patient or the family perceive the disease.

The referral of patients with severe asthma was addressed in Section III of the questionnaires. There are recommendations for the referral of asthma patients from primary care (PC) to emergency services7 and to specialised care in various guidelines.1,18,19 In response to items that explored whether patients with severe asthma are referred correctly, the panellists considered that it is not infrequent for patients with severe asthma followed up by the PC paediatrician to be referred late to the specialist. Consistent with this, it was agreed that the referral of patients with severe asthma to specialised care should be based on clear criteria agreed upon by PC paediatricians and paediatric asthma specialists, as opposed to the judgement of individual paediatricians. Furthermore, the panel agreed that PC paediatricians ought to refer patients with severe asthma to specialised care with high-priority status, even if the disease is controlled at the moment. On the other hand, no consensus was reached on whether all children with asthma receiving care from a PC paediatrician should be seen by the specialist at least once for evaluation.

The last section in the questionnaire attempted to clarify some concepts regarding the therapeutic approach to children with severe asthma. Most of the items in this section focused on the use of omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks circulating free immunoglobulin E, which plays a role in the clinical manifestations of allergic asthma.20 Clinical trials on patients aged more than 6 years have demonstrated the efficacy of omalizumab for the treatment of severe asthma.20–25 In the paediatric population in particular, there is evidence of statistically significant improvement in diurnal and nocturnal symptoms, a reduction in the use of medication,26 number of days with asthma symptoms,24 inflammatory markers, exacerbations, emergency room visits, hospital admissions and doctor's visits, an improvement in the quality of life, and the elimination of seasonal spikes in exacerbations associated with viral infections.20–25 The authors agree that the outcomes in everyday clinical practice are probably better than the outcomes achieved in clinical trials.27 The most recent guidelines1,10 place omalizumab in the step prior to treatment with oral corticosteroids. This recommendation is supported by level-A evidence.1

Finally, the panel also agreed that specific units for the diagnosis, control and treatment of children with severe asthma should be set up, as has already been done for adults.28

This study has the limitations inherent in the Delphi method. Chief among them are the difficulty in obtaining nuanced opinions from experts, and the potential for biases due to the influence of the sponsor. However, we tried to minimise the effects of these limitations, as the sponsors did not participate in the analysis and interpretations of the results or in the drafting and editing of the document.

In short, severe asthma is a relevant health problem in the paediatric associated with a high use of health care resources.1,8 While our knowledge of asthma has grown in recent years, there are still many uncertainties and controversial aspects when it comes to severe paediatric asthma.29,30 These uncertainties may be due, in part, to the heterogeneity of the disease and the lack of detailed knowledge of the mechanisms underlying its various phenotypes.31 There is also a wide variability in the definitions of severe asthma and in the followup, referral, and treatment recommendations. This document offers a few practical guidelines that may clarify some concepts and help the paediatrician optimise the management of this disease.

FundingThis project was funded and sponsored without restrictions by Novartis Farmacéutica S.A.

Conflicts of interestC.S.-S. and A.N. have participated in presentations and workshops for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

We want to thank the Nature Publishing Group Iberoamérica and Dr. Pablo Rivas for their help in editing this article.

Please cite this article as: Plaza AM, Ibáñez MDP, Sánchez-Solís M, Bosque-García M, Cabero MJ, Corzo JL, et al. Consenso para el abordaje del asma grave pediátrica en la práctica clínica habitual. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;84:122.