Mild head trauma is a frequent complaint in paediatric emergency departments. Several guidelines have been published in the last few years. However, significant variability can be appreciated in terms of the demand for image tests. The aim of this study is to determine the level of compliance with PECARN and AEP guidelines in the management of patients younger than 24 months old in four different hospitals.

Patients and methodsA multicenter retrospective study was conducted on patients presenting with mild head trauma between October 1st, 2011 and March 31st, 2013 in the emergency departments of four hospitals.

ResultsIn the analysis of the results obtained, only 1 of the 4 hospitals complied with the AEP guidelines in more than 50% of the patients. The other three hospitals had a level of compliance lower than 50%. Management was more suitable according to PECARN guidelines, with 3 of the 4 hospitals having a level of compliance greater than 50%. However, the best compliance achieved by a hospital was only of 70%.

ConclusionsThe study shows that the level of compliance with guidelines for management of mild head trauma in patients younger than 24 months old is low.

El traumatismo craneoencefálico leve es una causa común de atención en Urgencias Pediátricas. En los últimos años se han publicado diversos protocolos y guías de manejo de estos pacientes, pero aún existe una amplia variabilidad, especialmente en lo que a la realización de pruebas de imagen se refiere. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar el grado de concordancia del manejo de los pacientes menores de 24 meses a la guía clínica de la PECARN y al protocolo de la AEP en 4 centros diferentes.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo multicéntrico en el que se analiza a pacientes atendidos por traumatismo craneoencefálico leve entre el 1 de octubre del 2011 y el 31 de marzo del 2013 en los Servicios de Urgencias de 4 hospitales.

ResultadosAl analizar la concordancia del manejo de los pacientes con el protocolo de la AEP vemos que tan solo uno de los centros supera el 50% de los pacientes con un manejo acorde con el mismo. Los otros 3 centros mostraron un grado de concordancia inferior a esta cifra. El manejo sí es más adecuado para los estándares de las guías clínicas de PECARN, superando 3 de los centros el 50%, aunque el hospital con mejores cifras presentó un 70% solamente.

ConclusionesNuestro estudio muestra que la concordancia con las recomendaciones de las guías clínicas en el manejo del traumatismo craneoencefálico leve en los menores de 2 años es, en general, baja.

Minor head trauma (MHT) is a common complaint in paediatric emergency departments. In the United States it accounts for more than 60,000 hospital admissions in patients younger than 18 years and over 600,000 emergency room visits per year.1,2

Of all children with MHT, only 4–7% have a brain injury detectable by computed tomography (CT) and 0.5% an intracranial injury requiring urgent neurosurgery.3–5 Nevertheless, it is crucial that children with a clinically important traumatic brain injury requiring acute care are quickly identified, especially if they need surgery.

Cranial CT is the reference standard for emergently diagnosing traumatic brain injury. However, some brain lesions cannot be detected by CT.1,6,7 This method also has disadvantages, such as exposure to ionising radiation,8–12 the frequent need for sedation in young children, the removal of the patient from the direct supervision of the emergency doctor, the increased cost of medical care, and an increase in the time it takes to complete the patient's evaluation in the emergency department.

For those reasons several research groups have developed clinical guidelines in recent years to help address the issues that commonly arise in the evaluation of patients with MHT and to standardise the management of these patients.1,5,13 These guidelines are useful for assessing the different levels of risk in children with MHT, leading to a reduction in the rate of CT use.14

Of these guidelines, the one developed based on the largest cohort of patients was that of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN), which is considered the most valid for infants as well as older children.1,15

While none of the international clinical guidelines recommends the use of skull radiography to assess patients with MHT, this test is often used in emergency departments and several authors support its use for the detection of skull fractures, as the presence of a skull fracture in an infant is a risk factor for traumatic brain injury, and possibly the most relevant following changes in the level of consciousness.1,16–20 The protocols of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Pediatrics [AEP]) recommend its use in children younger than 2 years with MHT under specific circumstances (higher force mechanisms, high-speed motor vehicle collisions, falls from heights of more than 50cm, falls on hard surfaces, trauma from hard and blunt objects, presence of a significant cephalhaematoma, unwitnessed trauma with the possibility of a significant mechanism, or a history reported by parents that is vague or suggestive of abuse).16,21

Even in populations on which other guidelines have been developed, such as the Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH) and Children's Head Injury Algorithm for the Prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) Prediction Rules, skull radiography was used as a diagnostic tool in the detection of skull fractures in 4.7–23.4% of the patients, evincing that skull radiography is still being used in a large number of patients with MHT, even if its use has decreased compared to the past (64.9%).5,13,22 This is yet another proof of the significant variability that exists in the management of these patients, despite the availability of clinical practice guidelines and protocols.

Previous studies in the United States and Canada have shown great variability in the use of imaging studies in paediatric head trauma cases, with some evidence showing a lower number of imaging test requests in paediatric emergency departments than in general emergency departments.3,23–26

We do not know of any studies conducted in Europe that assessed the variability in the management of these patients.

The main aim of our study was to analyse the degree of compliance with the PECARN and AEP guidelines in the management of patients with MHT less than 24 months of age in 4 hospitals offering different levels of care. Our secondary aim was to assess the rate of skull radiography and cranial CT use in each facility, and the destination of patients on discharge from the emergency department.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a retrospective multicentric study on patients that received care for MHT in the emergency departments of four hospitals between October 1, 2011 and March 31, 2013. The hospitals were the Hospital Universitario Cruces (Barakaldo), a quaternary care level hospital where paediatric emergencies are managed by paediatricians dedicated exclusively to emergency care; the Hospital Universitario Río Hortega (Valladolid), a tertiary care hospital where paediatric emergencies are also managed by exclusively dedicated paediatricians; the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, a tertiary care hospital in which paediatric emergencies are managed by paediatricians that are not solely dedicated to emergency care, and the Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles (Ávila), a secondary level hospital where paediatric emergencies are managed by family physicians.

We reviewed the medical records and collected data on demographic characteristics, medical history, physical examination and diagnostic tests performed on the patients, as well as the subsequent outcomes. The study was approved by the ethics committee for clinical research of the Valladolid Oeste health area.

We defined MHT as a history or physical signs of trauma to the skull, brain, or scalp in a conscious infant or child that responds to verbal stimuli or to touch with a Glasgow Coma score equal or greater than 14.

We analysed the compliance with the AEP protocol for the management of head trauma and with the PECARN guidelines. The indications for imaging tests and/or in-hospital observation of both guidelines are shown in Table 1. We considered that the clinical management of a patient was in compliance with the AEP protocol if the decision to do a plain skull radiograph and/or cranial CT scan adhered to the indications in this protocol. If the indications for both were not met, the management was not considered compliant. Likewise, we considered the management of a patient to be in compliance with the PECARN guidelines when the indications for performing a cranial CT scan and for observation were both followed. When it came to clinical variables for which the PECARN guideline recommended either CT or observation, leaving the choice to the clinician, we considered either choice to be in compliance.

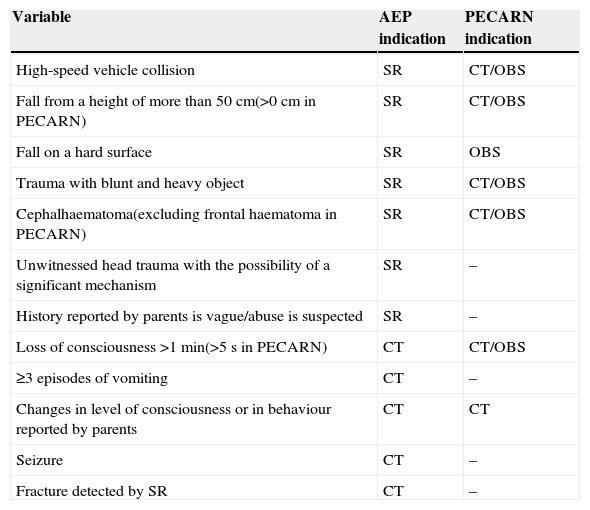

Indications for imaging tests and/or in-hospital observation according to the AEP protocol and the PECARN clinical guidelines.

| Variable | AEP indication | PECARN indication |

|---|---|---|

| High-speed vehicle collision | SR | CT/OBS |

| Fall from a height of more than 50cm(>0cm in PECARN) | SR | CT/OBS |

| Fall on a hard surface | SR | OBS |

| Trauma with blunt and heavy object | SR | CT/OBS |

| Cephalhaematoma(excluding frontal haematoma in PECARN) | SR | CT/OBS |

| Unwitnessed head trauma with the possibility of a significant mechanism | SR | – |

| History reported by parents is vague/abuse is suspected | SR | – |

| Loss of consciousness >1min(>5s in PECARN) | CT | CT/OBS |

| ≥3 episodes of vomiting | CT | – |

| Changes in level of consciousness or in behaviour reported by parents | CT | CT |

| Seizure | CT | – |

| Fracture detected by SR | CT | – |

AEP, Asociación Española de Pediatría; CT, cranial computed tomography; OBS, observation; PECARN: Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network; SR: plain skull radiograph.

We performed the statistical analysis with the Stata 12® software. We have expressed continuous variables as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range, depending on their distribution. We used the Shapiro–Wilk test to analyse the normality of the distribution of continuous variables. We have expressed categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages. Differences in central tendency were analysed by means of the chi square test for categorical variables and Student's t test in continuous variables.

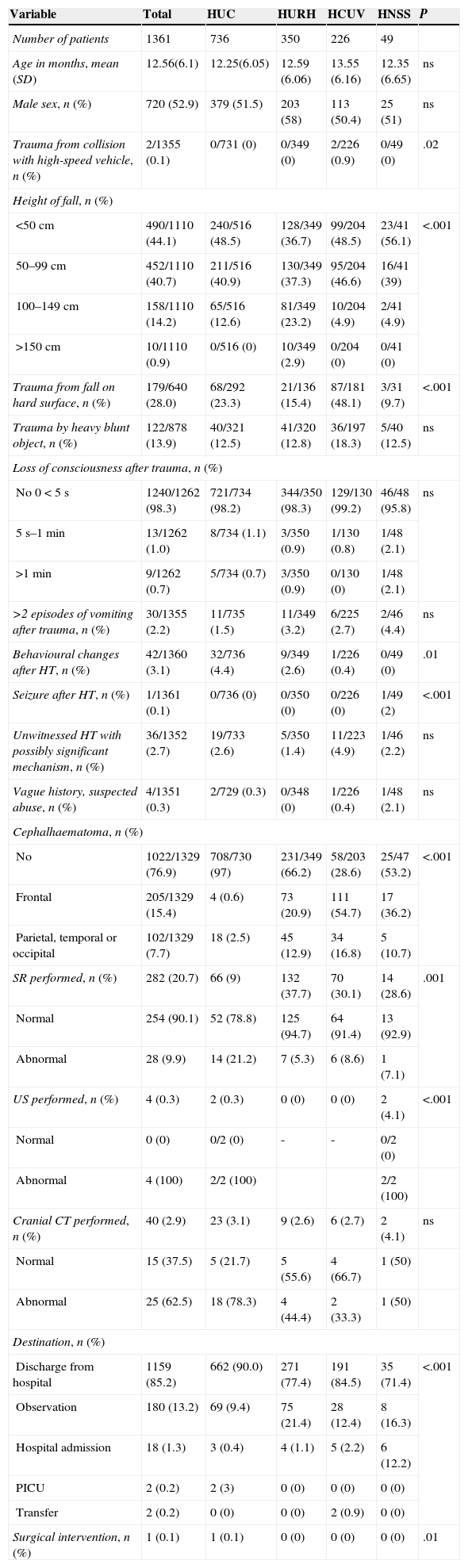

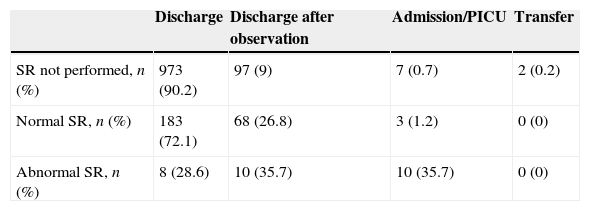

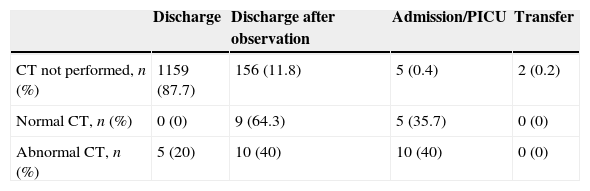

ResultsDuring the period under study, 1361 patients received care in the four hospitals. Table 2 shows the distribution of patients by centre and by clinical characteristics, diagnostic tests and patient destination. Tables 3 and 4 show patient destinations in relation to the results of the diagnostic tests performed.

Data for history, physical examination, diagnostic tests and destination of the patients in each hospital.

| Variable | Total | HUC | HURH | HCUV | HNSS | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1361 | 736 | 350 | 226 | 49 | |

| Age in months, mean (SD) | 12.56(6.1) | 12.25(6.05) | 12.59 (6.06) | 13.55 (6.16) | 12.35 (6.65) | ns |

| Male sex, n (%) | 720 (52.9) | 379 (51.5) | 203 (58) | 113 (50.4) | 25 (51) | ns |

| Trauma from collision with high-speed vehicle, n (%) | 2/1355 (0.1) | 0/731 (0) | 0/349 (0) | 2/226 (0.9) | 0/49 (0) | .02 |

| Height of fall, n (%) | ||||||

| <50cm | 490/1110 (44.1) | 240/516 (48.5) | 128/349 (36.7) | 99/204 (48.5) | 23/41 (56.1) | <.001 |

| 50–99cm | 452/1110 (40.7) | 211/516 (40.9) | 130/349 (37.3) | 95/204 (46.6) | 16/41 (39) | |

| 100–149cm | 158/1110 (14.2) | 65/516 (12.6) | 81/349 (23.2) | 10/204 (4.9) | 2/41 (4.9) | |

| >150cm | 10/1110 (0.9) | 0/516 (0) | 10/349 (2.9) | 0/204 (0) | 0/41 (0) | |

| Trauma from fall on hard surface, n (%) | 179/640 (28.0) | 68/292 (23.3) | 21/136 (15.4) | 87/181 (48.1) | 3/31 (9.7) | <.001 |

| Trauma by heavy blunt object, n (%) | 122/878 (13.9) | 40/321 (12.5) | 41/320 (12.8) | 36/197 (18.3) | 5/40 (12.5) | ns |

| Loss of consciousness after trauma, n (%) | ||||||

| No 0<5s | 1240/1262 (98.3) | 721/734 (98.2) | 344/350 (98.3) | 129/130 (99.2) | 46/48 (95.8) | ns |

| 5s–1min | 13/1262 (1.0) | 8/734 (1.1) | 3/350 (0.9) | 1/130 (0.8) | 1/48 (2.1) | |

| >1min | 9/1262 (0.7) | 5/734 (0.7) | 3/350 (0.9) | 0/130 (0) | 1/48 (2.1) | |

| >2 episodes of vomiting after trauma, n (%) | 30/1355 (2.2) | 11/735 (1.5) | 11/349 (3.2) | 6/225 (2.7) | 2/46 (4.4) | ns |

| Behavioural changes after HT, n (%) | 42/1360 (3.1) | 32/736 (4.4) | 9/349 (2.6) | 1/226 (0.4) | 0/49 (0) | .01 |

| Seizure after HT, n (%) | 1/1361 (0.1) | 0/736 (0) | 0/350 (0) | 0/226 (0) | 1/49 (2) | <.001 |

| Unwitnessed HT with possibly significant mechanism, n (%) | 36/1352 (2.7) | 19/733 (2.6) | 5/350 (1.4) | 11/223 (4.9) | 1/46 (2.2) | ns |

| Vague history, suspected abuse, n (%) | 4/1351 (0.3) | 2/729 (0.3) | 0/348 (0) | 1/226 (0.4) | 1/48 (2.1) | ns |

| Cephalhaematoma, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 1022/1329 (76.9) | 708/730 (97) | 231/349 (66.2) | 58/203 (28.6) | 25/47 (53.2) | <.001 |

| Frontal | 205/1329 (15.4) | 4 (0.6) | 73 (20.9) | 111 (54.7) | 17 (36.2) | |

| Parietal, temporal or occipital | 102/1329 (7.7) | 18 (2.5) | 45 (12.9) | 34 (16.8) | 5 (10.7) | |

| SR performed, n (%) | 282 (20.7) | 66 (9) | 132 (37.7) | 70 (30.1) | 14 (28.6) | .001 |

| Normal | 254 (90.1) | 52 (78.8) | 125 (94.7) | 64 (91.4) | 13 (92.9) | |

| Abnormal | 28 (9.9) | 14 (21.2) | 7 (5.3) | 6 (8.6) | 1 (7.1) | |

| US performed, n (%) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.1) | <.001 |

| Normal | 0 (0) | 0/2 (0) | - | - | 0/2 (0) | |

| Abnormal | 4 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 2/2 (100) | |||

| Cranial CT performed, n (%) | 40 (2.9) | 23 (3.1) | 9 (2.6) | 6 (2.7) | 2 (4.1) | ns |

| Normal | 15 (37.5) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (50) | |

| Abnormal | 25 (62.5) | 18 (78.3) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (50) | |

| Destination, n (%) | ||||||

| Discharge from hospital | 1159 (85.2) | 662 (90.0) | 271 (77.4) | 191 (84.5) | 35 (71.4) | <.001 |

| Observation | 180 (13.2) | 69 (9.4) | 75 (21.4) | 28 (12.4) | 8 (16.3) | |

| Hospital admission | 18 (1.3) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (1.1) | 5 (2.2) | 6 (12.2) | |

| PICU | 2 (0.2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Transfer | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Surgical intervention, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .01 |

The denominators represent the number of medical records in which the variable had been documented.

CT, computed tomography; HCUV, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid; HNSS, Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles; HT, head trauma; HUC, Hospital Universitario Cruces; HURH, Hospital Universitario del Río Hortega; ns: not significant; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; SD, standard deviation; SR, skull radiography; US, ultrasound.

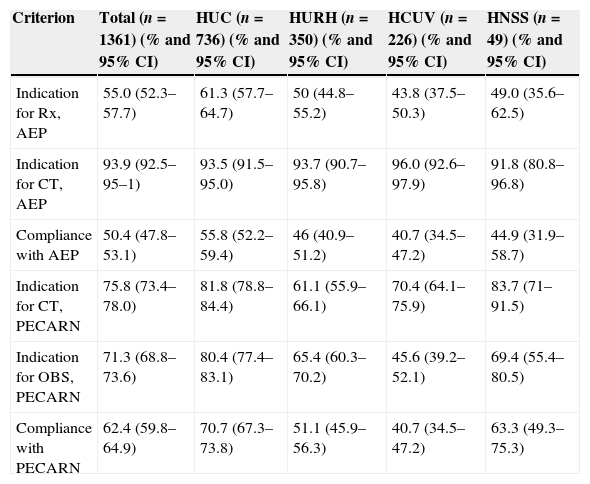

Lastly, Table 5 shows the percentage of patients in each centre that were managed in compliance with the indications in the AEP protocol and the percentage of patients managed in compliance with the indications in the PECARN guidelines.

Proportion of patients in each centre managed in compliance with the AEP and/or PECARN guidelines.

| Criterion | Total (n=1361) (% and 95% CI) | HUC (n=736) (% and 95% CI) | HURH (n=350) (% and 95% CI) | HCUV (n=226) (% and 95% CI) | HNSS (n=49) (% and 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication for Rx, AEP | 55.0 (52.3–57.7) | 61.3 (57.7–64.7) | 50 (44.8–55.2) | 43.8 (37.5–50.3) | 49.0 (35.6–62.5) |

| Indication for CT, AEP | 93.9 (92.5–95–1) | 93.5 (91.5–95.0) | 93.7 (90.7–95.8) | 96.0 (92.6–97.9) | 91.8 (80.8–96.8) |

| Compliance with AEP | 50.4 (47.8–53.1) | 55.8 (52.2–59.4) | 46 (40.9–51.2) | 40.7 (34.5–47.2) | 44.9 (31.9–58.7) |

| Indication for CT, PECARN | 75.8 (73.4–78.0) | 81.8 (78.8–84.4) | 61.1 (55.9–66.1) | 70.4 (64.1–75.9) | 83.7 (71–91.5) |

| Indication for OBS, PECARN | 71.3 (68.8–73.6) | 80.4 (77.4–83.1) | 65.4 (60.3–70.2) | 45.6 (39.2–52.1) | 69.4 (55.4–80.5) |

| Compliance with PECARN | 62.4 (59.8–64.9) | 70.7 (67.3–73.8) | 51.1 (45.9–56.3) | 40.7 (34.5–47.2) | 63.3 (49.3–75.3) |

AEP, Asociación Española de Pediatría; CT, computer tomography; HCUV, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid; HNSS, Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles; HUC, Hospital Universitario Cruces; HURH, Hospital Universitario del Río Hortega; OBS, observation; PECARN: Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network; Rx, radiography.

In this study, we did a retrospective analysis of the management of children with MHT younger than 2 years in four hospitals offering different levels of care. We found no significant differences in the characteristics of head trauma between the four hospitals. It is worth noting that variables such as trauma from falling on a hard surface or by a heavy blunt object are only documented in 47% and 65% of the medical records, respectively, even though they are indications for performing a skull radiograph according to the AEP protocol.

However, we did find considerable differences in the proportion of patients that presented with cephalhaematoma at the time of evaluation in one of the hospitals compared to the other three. A possible explanation is that there is no consensus as to what should be considered a cephalhaematoma, with hospitals with a lesser degree of specialisation in paediatric emergencies being more likely to consider a lesion to be a cephalhaematoma.

There was a striking intercentre variability in the proportion of patients in which a skull radiograph was performed, as well as in the percentage of the skull radiographs with abnormal findings. These results are consistent with those reported in British studies previous to the publication of the CHALICE clinical guidelines.13,22 The use of CT, on the other hand, was similar across the four centres.

Our results show that the percentage of patients admitted to the hospital or that remained under observation for longer than 2h was greater in patients that underwent imaging tests. This is particularly remarkable in those patients in whom the test performed was a plain skull radiograph that yielded no abnormal findings, of whom 1 out of 4 remained under observation or was admitted to the hospital, with the test results seemingly having no effect on the approach of the paediatrician.

On the other hand, we observed that while 28 patients had an abnormal radiograph, only one of them required surgical intervention. This patient was a 4-month-old girl with a cephalhaematoma at a location other than the frontal bone, which indicates a cranial CT scan in the PECARN guidelines, a test that also yielded abnormal findings.

As for the AEP protocol, we observed that the percentage of patients managed in compliance to it only exceeded 50% in one of the hospitals. The other three centres had lower levels of compliance. However, the management of these patients was more appropriate in relation to the PECARN clinical guidelines, with three hospitals exceeding 50%, although the hospital with the highest compliance only reached a 70% rate. It seems paradoxical that there was a higher compliance with international guidelines, as in principle they should be less well-known than domestic protocols. This can probably be explained by a low adherence of paediatricians to the current protocol of the AEP rather than a greater knowledge of the international guidelines, as compliance with the latter is also not very high.

There are several limitations to our study. On one hand, the sample was not very large, which makes the confidence intervals very large for some of the centres. Furthermore, we ought to mention that one of the hospitals, the Hospital Clínico Universitario, lacks an observation room in its emergency department, so there may be a bias in the rate of compliance with the PECARN indications for observation. On the other hand, our study collected data on only four centres, so its results should be interpreted with caution. However, we believe that the variability found in our results accurately reflects how MHT is currently managed in Spain. Last of all, as we previously noted, not all variables were documented in each discharge summary. This is a common limitation in retrospective studies, which represent the only method of data gathering allowing the analysis of the real-world management of patients without producing an observer bias.

ConclusionsThe management of MHT was in low compliance with the clinical guidelines under study, and compliance with the PECARN guidelines was higher. We found a high intercentre variability in the request for plain skull radiographs in these patients.

A study on a larger scale is needed to analyse how MHT is managed in paediatric emergency departments in all of Spain as a first step towards standardising the management of these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Velasco R, Arribas M, Valencia C, Zamora N, Fernández SM, Lobeiras A, et al. Adecuación del manejo diagnóstico del traumatismo craneoencefálico leve en menores de 24 meses a las guías de práctica clínica de PECARN y AEP. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:166–172.