Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) is a rare disease in adolescents, in whom the incidence is 0.5%. In adults, it has a multifactorial aetiology with no determining factor, primarily affects women (ratio, 2–3:1) aged 20–40 years, and in some cases its onset is associated with an infectious cause (usually viral). In adulthood, CFS is diagnosed based on clinical manifestations and is a diagnosis of exclusion (Table 1),1 and while the literature includes descriptions of differences in the paediatric population, few series present data on its particular features in this age group. The management is symptomatic with the goal of improving quality of life. Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), melatonin, methylphenidate, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and graded exercise has been proven to be effective in these patients.

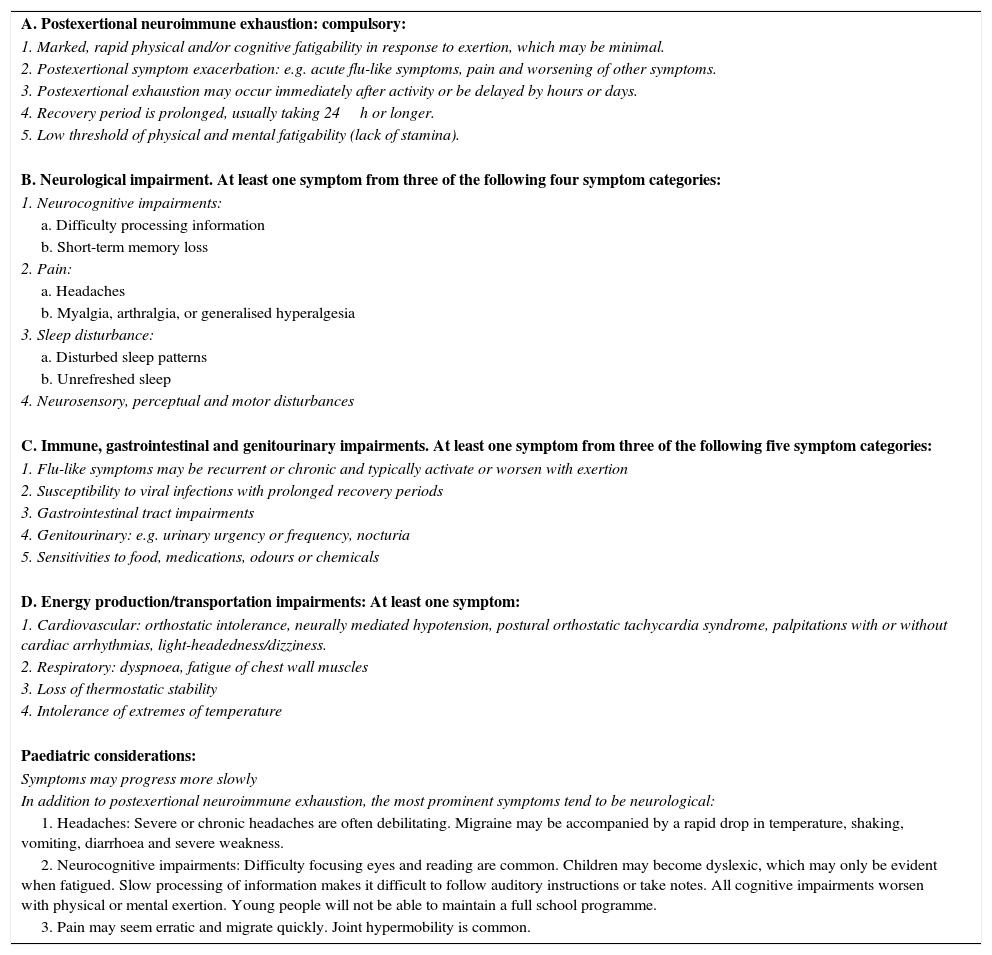

2011 International Consensus Criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis in adults, and paediatric considerations.1

| A. Postexertional neuroimmune exhaustion: compulsory: |

| 1. Marked, rapid physical and/or cognitive fatigability in response to exertion, which may be minimal. |

| 2. Postexertional symptom exacerbation: e.g. acute flu-like symptoms, pain and worsening of other symptoms. |

| 3. Postexertional exhaustion may occur immediately after activity or be delayed by hours or days. |

| 4. Recovery period is prolonged, usually taking 24h or longer. |

| 5. Low threshold of physical and mental fatigability (lack of stamina). |

| B. Neurological impairment. At least one symptom from three of the following four symptom categories: |

| 1. Neurocognitive impairments: |

| a. Difficulty processing information |

| b. Short-term memory loss |

| 2. Pain: |

| a. Headaches |

| b. Myalgia, arthralgia, or generalised hyperalgesia |

| 3. Sleep disturbance: |

| a. Disturbed sleep patterns |

| b. Unrefreshed sleep |

| 4. Neurosensory, perceptual and motor disturbances |

| C. Immune, gastrointestinal and genitourinary impairments. At least one symptom from three of the following five symptom categories: |

| 1. Flu-like symptoms may be recurrent or chronic and typically activate or worsen with exertion |

| 2. Susceptibility to viral infections with prolonged recovery periods |

| 3. Gastrointestinal tract impairments |

| 4. Genitourinary: e.g. urinary urgency or frequency, nocturia |

| 5. Sensitivities to food, medications, odours or chemicals |

| D. Energy production/transportation impairments: At least one symptom: |

| 1. Cardiovascular: orthostatic intolerance, neurally mediated hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, palpitations with or without cardiac arrhythmias, light-headedness/dizziness. |

| 2. Respiratory: dyspnoea, fatigue of chest wall muscles |

| 3. Loss of thermostatic stability |

| 4. Intolerance of extremes of temperature |

| Paediatric considerations: |

| Symptoms may progress more slowly |

| In addition to postexertional neuroimmune exhaustion, the most prominent symptoms tend to be neurological: |

| 1. Headaches: Severe or chronic headaches are often debilitating. Migraine may be accompanied by a rapid drop in temperature, shaking, vomiting, diarrhoea and severe weakness. |

| 2. Neurocognitive impairments: Difficulty focusing eyes and reading are common. Children may become dyslexic, which may only be evident when fatigued. Slow processing of information makes it difficult to follow auditory instructions or take notes. All cognitive impairments worsen with physical or mental exertion. Young people will not be able to maintain a full school programme. |

| 3. Pain may seem erratic and migrate quickly. Joint hypermobility is common. |

We present a series of 12 consecutive cases of CFS diagnosed in patients aged less than 21 years in the adolescent medicine unit of a tertiary care hospital between January 2007 and December 2012. We collected data for demographic variables, symptoms, personal and family history, diagnostic tests performed, treatment given, and response to treatment. We performed the statistical analysis with the Stata® v.12.0 software.

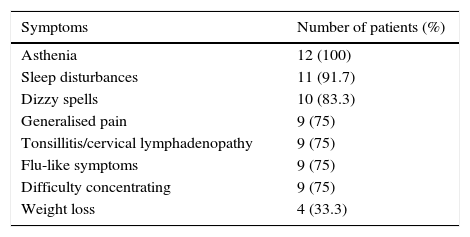

We recruited twelve patients, seven male and five female (ratio, 1.4:1). Their median age was 15 years (range, 12–17 years). The median time to diagnosis was 12 months (range, 3–34 months). The duration of school absenteeism ranged between zero and twenty-four months (median, 3 months). Table 2 presents the frequency of symptoms.

The most salient finding in relation to the personal histories of the patients consisted of viral infections prior to the onset of CFS: four cases of infection by EBV and one by parvovirus. Two patients had psychosomatic disorders that predated the onset of CFS. When it came to a positive history in first-degree relatives, two patients had a family history of psychiatric disorders, three of fibromyalgia and two of poliomyelitis. A complete blood count, electrolyte panel, kidney and liver function panel, thyroid panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serology testing were performed in all patients. Additional tests were required in 71.4% of patients to rule out other diagnoses. All patients were managed with CBT and a graded exercise programme. The prescribed symptomatic treatment consisted of melatonin for sleep-onset insomnia in eight patients, SSRIs for chronic pain in two, and methylphenidate for inattention in five. The median duration of followup was 12 months (range, 2–90 months). When it came to the outcomes, more than half of the patients (58%) experienced a complete resolution, with a median time elapsed to discharge of seven months (range, 2–14 months). The rest experienced partial improvement.

In the paediatric age group, CFS is a disease that greatly impacts quality of life, as the onset of symptoms is abrupt and it leads to prolonged absences from school, so it has been proposed that three months of asthenia be considered a diagnostic criterion.2 In adult series there is a predominance of the female sex that is maintained in some paediatric series, and that becomes more pronounced with increasing age.2 However, the ratio described for the paediatric age group approximates one,3 which is consistent with our series. As for the cause, no evidence has been found so far of an infectious aetiology,2 but it seems that a heterogeneous group of pathogens may be capable of triggering the disease, as a history of infection preceding the onset of symptoms has been found in 22–88% of patients.3 In our series, too, 42% of patients had positive serology tests for different viruses. Bould et al. observed that the prevalence of depression was 10 times higher in adolescents with CFS compared to the general population.4 In our series, depression was not diagnosed in any of the patients during the followup. There is evidence that CBT is effective in two thirds of adolescents with CFS.5 The multimodal approach applied in our study included pharmacological treatment, CBT and graded exercise. This achieved complete resolution of the disease in 58% of the patients and considerable improvement in the rest, which is consistent with other series.6

In our setting, chronic fatigue syndrome is underdiagnosed in children and adolescents; this impacts quality of life, and it is important that it be diagnosed and treated early. The diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations. The approaches used most frequently in its management are graded exercise, CBT and symptomatic treatment.

Please cite this article as: Calle Gómez Á, Delgado Díez B, Campillo i López F, Salmerón Ruiz MA, Casas Rivero J. Síndrome de fatiga crónica en adolescentes. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;85:318–320.