The process of care and assistance from birth to the starting of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) is crucial in order to improve its effectiveness and prevent the worsening of hypoxic-ischaemic injury.

MethodsA national cross-sectional study carried out in 2015 by use of a questionnaire sent to all level III units on the care of the newborn≥35 weeks gestation within the first hours of life after a perinatal asphyxia event. According to clinical practice guidelines, the quality of care was compared between the hospitals that carried out or did not carry out TH, and according to the level of care.

ResultsA total of 89/90 hospitals participated, of which 57/90 performed TH. They all used resuscitation protocols and turned off the radiant warmer after stabilisation. All of them performed glucose and blood gas analysis, monitored the central temperature, put the newborn on a diet, and performed at least two examinations for the diagnosis of hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Greater than one-third (35%) of hospitals did not have amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram, and 6/57 were TH-hospitals. The quality of care among hospitals with and without TH was similar, childbirth being better in those that performed TH, and those with a higher level of care. Level IIIc hospitals had higher scores than the others. The TH-hospitals mentioned not always having neonatologists with experience in neurological assessment and interpretation of amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram (25%), or in brain ultrasound (62%).

ConclusionsIn response to the recommendations of the asphyxiated newborn, there is a proper national health care standard with differences according to the level of care and whether TH is offered. More amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram devices are necessary, as well as more neonatologists trained in the evaluations that will be required by the newborn with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy.

El proceso asistencial hasta el inicio de la hipotermia terapéutica (HT) es crucial para mejorar su efectividad y prevenir el agravamiento del daño hipóxico-isquémico.

MétodoEstudio transversal nacional realizado en 2015 mediante cuestionario a todas las unidades nivel iii sobre la asistencia al recién nacido (RN) con asfixia perinatal en las primeras horas de vida. Se comparó la calidad asistencial entre los hospitales que realizaban o no HT y según el nivel asistencial, de acuerdo a las guías de práctica clínica.

ResultadosParticiparon 89/90 hospitales, 57/90 realizaban HT. Todos utilizaban protocolos de reanimación y apagaban la cuna tras estabilización. Fue universal realizar medición de glucemia y gasometría, monitorizar la temperatura, dejar al RN a dieta y realizar al menos 2 exploraciones para el diagnóstico de encefalopatía hipóxico-isquémica. El 35% no disponía de electroencefalograma integrado por amplitud; 6/57 eran hospitales que realizaban HT. La calidad asistencial entre los hospitales con/sin HT fue similar, siendo mejor la del parto en los que hacían HT, y la de aquellos con mayor nivel asistencial. El 25% de aquellos que realizaban HT no tenían neonatólogos con experiencia en la exploración neurológica o en la interpretación del electroencefalograma integrado por amplitud; ni en la realización de ecografía cerebral en el 62%.

ConclusionesAtendiendo a las recomendaciones del RN asfíctico, existe un adecuado estándar asistencial nacional, con diferencias según el nivel asistencial y si realizan o no hipotermia. Son necesarios más equipos de electroencefalograma integrado por amplitud y formación de los neonatólogos en las evaluaciones que requerirá el RN con encefalopatía hipóxico-isquémica.

The considerable medical, familial, social and legal ramifications of perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) in term or late preterm newborns (NBs) make it a significant public health and social problem.1

In Spain, the Sociedad Española de Neonatología (Spanish Society of Neonatology) published standard guidelines for the use of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) in clinical practice in 2011,2 and a group of experts developed an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the integrated care of newborns with HIE in 2014.3 The evidence on the effectiveness of TH in everyday clinical practice has shown outcomes that are better compared to those obtained in early clinical trials.4 In all likelihood, of all the factors that contribute to this gap between efficacy and effectiveness, the most relevant are those at play in the first hours of life: adequate resuscitation in the delivery room, early initiation of TH, and control of factors that may aggravate the hypoxic-ischaemic insult before and during TH. However, there are hardly any published recommendations on the care delivered from birth to initiation of TH, a crucial window in which it is possible to act on these factors, enhancing the neuroprotective effects of hypothermia.5–8

The objectives of our nationwide study were: (1) to establish how level III neonatal units manage NBs with perinatal asphyxia in the first 6h post birth, and (2) to determine whether there are differences between units that offer TH and units that transfer NBs with asphyxia to referral hospitals to receive this treatment, and between different care levels within tertiary care.

MethodsWe conducted a multicentre cross-sectional study to analyse the management in the first 6h of life of NBs delivered at or after 35 weeks’ gestation with perinatal asphyxia by means of an online questionnaire. We conducted the survey in 2015 and included every tertiary care hospital (public or private) that had a Level III neonatal unit in Spain.9 We requested that the clinician most experienced in the management of HIE in each centre should be the one to complete the questionnaire.

Tables 1 and 2 present the 23 items of questionnaire that addressed the care of NBs that met the criteria for asphyxia in the first hours of life. We defined asphyxia as the presence of at least 1 of the following: (1) umbilical artery pH or blood pH at 1h of life ≤7 or base deficit ≥16; (2) 5-min Apgar score ≤5; (3) need for advanced resuscitation (intubation and/or chest compressions and/or administration of drugs). Table 3 presents the 8 items concerning the availability of health care professionals with experience in the management of NBs with HIE in each of the hospitals that practiced TH at the time data collection ended (June 2015).

Items concerning the care of newborns with perinatal asphyxia in the delivery room.

| Hospitals that do not use TH | Hospitals that used TH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearly always | Frequently | Rarely or never | Nearly always | Frequently | Rarely or never | |

| In complicated deliveries, the staff present in the delivery room include: | ||||||

| 1. A paediatrician | 32 (100) | 0 | 0 | 55 (96) | 0 | 2 (4) |

| 2. A paediatrician specialised in neonatology | 22 (69) | 10 (31) | 0 | 43 (75) | 12 (21) | 2 (4) |

| 3. A nurse-midwife | 31 (97) | 0 | 1 (3) | 52 (91) | 3 (5) | 2 (4) |

| 4. A nurse from the neonatal unit | 8 (25) | 9 (28) | 15 (47) | 14 (25) | 10 (18) | 33 (58) |

| If the NB exhibits signs of perinatal asphyxia at birth: | ||||||

| 5. There is a specific management protocol for the delivery room | 30 (94) | 2 (6) | 0 | 53 (93) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| 6. Use of bicarbonate is avoided even if pH<7.00 | 26 (81) | 2 (6) | 4 (13) | 51 (89) | 2 (4) | 4 (7) |

| 7. Administration of calcium is avoided even if NB requires advanced resuscitationa | 26 (81) | 4 (13) | 2 (6) | 55 (96) | 0 | 2 (4) |

| 8. Heat sources are turned off once NB recovers a normal heart rate | 26 (81) | 4 (13) | 2 (6) | 55 (96) | 2 (4) | 0 |

| 9. Heat in the transport incubator is off during NB transport | 29 (91) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 56 (98) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| 10. NB is admitted to NICU for observation | 31 (97) | 1 (3) | 0 | 54 (95) | 3 (5) | 0 |

| 11. If NB recovers quickly, NB stays with the mother | 2 (6) | 7 (22) | 23 (72) | 2 (4) | 12 (21) | 43 (75) |

NB, newborn; TH, therapeutic hypothermia.

Items concerning the care of newborns with perinatal asphyxia in the first 6h of life.

| Hospitals that did not use TH | Hospitals that used TH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearly always | Frequently | Rarely or never | Nearly always | Frequently | Rarely or never | |

| In the first 6hours port birth in NBs with perinatal asphyxia | ||||||

| 12. Implementation of a specific care protocol | 26 (81) | 5 (16) | 1 (3) | 52 (91) | 5 (9) | 0 |

| 13. Measurement of blood gases | 32 (100) | 0 | 0 | 57 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| 14. Measurement of blood glucose | 32 (100) | 0 | 0 | 57 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| 15. Absolute fasting | 32 (100) | 0 | 0 | 56 (98) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| 16. Absolute fasting with fluid therapy | 32 (100) | 0 | 0 | 48 (84) | 8 (14) | 1 (2) |

| 17. Monitoring of core body temperature, continuous or intermittent/30min | 22 (69) | 10 (31) | 0 | 42 (74) | 12 (21) | 3 (5) |

| 18. Maintenance of core temperature <36°C | 27 (84) | 3 (9) | 2 (6) | 40 (70) | 12 (21) | 5 (9) |

| 19. If aEEG available, cerebral function monitoringa | 5 (16) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 38 (67) | 8 (14) | 5 (9) |

| 20. Number of aEEG devices | ||||||

| ≥2 | 0 | 12 (21) | ||||

| 1 | 7 (22) | 39 (68) | ||||

| None | 25 (78) | 6 (11) | ||||

| 21. How many assessments do you perform to grade the severity of HIE? | ||||||

| ≥2 | 29 (91) | 53 (93) | ||||

| 1 | 3 (9) | 4 (7) | ||||

| None | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 22. What scale do you use to grade the severity of HIE? | ||||||

| García-Alix | 20 (63) | 39 (68) | ||||

| Sarnat | 12 (38) | 13 (23) | ||||

| Other | 0 | 5 (9) | ||||

| None | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 23. In the scale that you use, which item do you consider most important | ||||||

| Remaining awake and alert | 30 (94) | 50 (88) | ||||

| Muscle tone | 1 (3) | 6 (10) | ||||

| Movement | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | ||||

| Other | 0 | 0 | ||||

aEEG, amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram; HIE, hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy; NB, newborn; TH, therapeutic hyperthermia.

Items addressed to hospitals that performed therapeutic hypothermia concerning the availability of health care professionals experienced in the management of newborns with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy.

| Nearly always | Frequently | Rarely or never | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24. Professionals trained in neonatal neurologic assessment | |||

| a. Neonatologist | 40 (75) | 12 (23) | 1 (2) |

| b. Neurologist | 28 (53) | 14 (26) | 11 (21) |

| 25. Neonatologists trained in aEEG interpretation | 40 (75) | 8 (15) | 5 (10) |

| 26. Professionals trained in brain neuroimaging | |||

| a. Neonatologist trained in MRI interpretation | 7 (13) | 20 (38) | 26 (49) |

| b. Neonatologist trained in ultrasound and Doppler ultrasound | 20 (38) | 15 (28) | 18 (34) |

| c. Radiologist trained in ultrasound and Doppler ultrasound | 34 (64) | 11 (21) | 8 (15) |

| d. Radiologist trained in MRI interpretation | 39 (74) | 12 (23) | 2 (3) |

| 27. Neonatologist trained in echocardiography/Paediatric cardiologist | 30 (57) | 16 (30) | 7 (13) |

| 28. Nursing staff with specific training on HIE | 42 (79) | 8 (15) | 3 (6) |

| 29. Specific care plan developed by nursing staff | 38 (72) | 6 (11) | 9 (17) |

| 30. Nurse–patient ratio equal to the ratio for critically ill patients | 43 (81) | 9 (17) | 1 (2) |

| 31. Psychologist to support parents in this situation | 15 (28) | 11 (21) | 27 (51) |

Fifty-three of the 57 hospitals that used hypothermia answered the questions.

aEEG, amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram; HIE, hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

To rate the quality of the care offered by each hospital, we assigned a score to each item: 4 points if the practice “nearly always” adhered to the care standard recommended in clinical practice guidelines, 3 points if the practice was implemented “frequently” or 1 point when the answer was “rarely or never”. We categorised hospitals as delivering “optimal care” if they scored 4 points in all items, “acceptable care” if any of the items had a score of 3 and none had a score of 1, and “care that could improve” if any of the items had a score of 1. We excluded the most controversial items from the calculation of the ratings (items 11, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 23 and 31). We combined the scores of the items that referred to the same aspect of care: 1–2, 3–4, 24a–24b, 26a–26d, 26b–26c. For the 3 items that had multiple-choice answers (20, 21 and 22), we gave a score of 1 point if the answer was “none” and a score of 4 points otherwise (Tables 1–3). The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the coordinating hospital.

Statistical analysisWe have expressed descriptive data as absolute frequencies and percentages. To make comparisons, we used the chi square test and Fisher exact test for qualitative variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test for quantitative variables. We defined statistical significance as a p-value of less than 0.05.

ResultsOf the total of 90 level III neonatal units in Spain, 89 submitted the information we had requested.

When it came to the management at birth (Table 1), most hospitals (98%) reported that complicated deliveries were managed by a neonatologist and a midwife, in some cases further assisted by a neonatal nurse. In addition, practically every hospital reported having resuscitation protocols, turning off exogenous heat sources once the NB had stabilised, and rarely using calcium or sodium bicarbonate during resuscitation. Furthermore, it was common practice to transfer the NB to the neonatal unit even if they recovered quickly, although in the latter case some hospitals (25%) let NBs remain with their mothers.

Table 2 shows the results concerning the interventions in the first 6h of life. Most hospitals had specific care protocols for this window, with periodic measurement of blood glucose levels and gases, monitoring of body temperature to maintain it under 36°C, and fasting of the NB with administration of intravenous fluids. When it came to assessment of HIE, most units (92%) performed at least 2 assessments in the first 6h of life, with 94% using the severity scales proposed by García-Alix10 and Sarnat11 for this purpose, and 90% considering the ability to be awake and alert the most relevant item of the scale. As for the use of amplitude-integrated electroencephalography (aEEG) in the first 6h of life, 58 of the 89 hospitals (65%) reported this method being available: 51 (89%) of the 57 units that offered TH, and 7 (22%) of the 32 units that did not offer HT (p<.05). Of the hospitals where aEEG was available, 90% reported using it nearly always or frequently.

We received data on the availability of health care professionals with experience in the management of NBs with HIE from 53 of the 57 hospitals that used TH (Table 3). Most hospitals always had on site personnel trained to perform neurologic assessments (89%), cranial ultrasound examinations (87%) interpretation of magnetic resonance scans (75%) and echocardiography assessments (57%). However, 25% of hospitals did not always have on site a neonatologist with experience in the neurologic assessment of newborns or the interpretation of aEEG, and 62% did not always have on site someone that could do a cranial ultrasound. Most hospitals reported an adequate nurse-to-patient ratio, although there were no specific nursing protocols in 28% of hospitals, or nurses experienced in the care of these newborns in 21%. Lastly, more than 50% of hospitals did not have resources to offer specialised psychological support to the parents and families of this children.

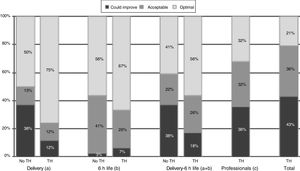

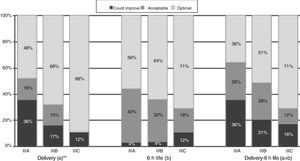

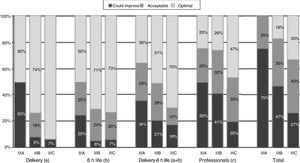

When it came to the score of the care offered in the delivery room and the first 6h of life, 25% of the 89 hospitals were in the category of “care that could improve,” although they had high scores, with a median of 54.5 points (range, 46–56) in hospitals that did not offer TH compared to 56 (range, 49–56) in the rest of hospitals (p=.052) (Table 4). A greater proportion of hospitals that offered TH achieved the classification of “optimal care” compared to those that did not practice TH, especially during resuscitation (p=.015) (Fig. 1). The analysis by level of care showed that the quality of care improved with the level of care of the unit, both overall and in the subset of hospitals that used TH (Figs. 2 and 3).

Comparison of scores received by the 89 hospitals that offered TH versus those that did not, and those that offered TH versus those that did not.

| Offered TH yes/no | Level of care | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items concerning | No (n=32) | Yes (n=57) | P | IIIA (n=25) | IIIB (n=47) | IIIC (n=17) | p |

| Care during deliverya | 31.5 (25–32) | 32 (26–32) | .007 | 31 (25–32) | 32 (25–32) | 32 (26–32) | .034 |

| Care in the first 6h of lifeb | 24 (20–24) | 24 (20–24) | .426 | 24 (21–24) | 24 (20–24) | 24 (20–24) | .827 |

| Care during delivery and the first 6h of lifea,b | 54.5 (46–56) | 56 (49–56) | .052 | 55 (48–56) | 56 (47–56) | 56 (46–56) | .105 |

| Availability of experienced health care professionalsc,d | – | 34 (21–36) | – | 31.5 (27–36) | 33 (24–36) | 35 (21–36) | .129 |

| All of the abovea,b,c,d | – | 89 (72–92) | – | 84 (81–90) | 88.5 (77–92) | 91 (72–92) | .027 |

TH, therapeutic hypothermia.

Data expressed as median (range).

Quality of care in hospitals that offered therapeutic hypothermia versus those that did not. No TH, hospital not offering therapeutic hypothermia; TH, hospital offering therapeutic hypothermia. (a) Includes items 5–10, and combined items 1–2 and 3–4. (b) Includes items 12–14, 17, 21, 22. (c) Includes items 20, 25, 27–30, and combined items 24a–24b, 26a–26d and 26b–26c. Total=(a)+(b)+(c). *P=.015 (chi square test comparing “optimal care” versus “acceptable care/care that could improve”).

Quality of care in tertiary care hospitals that offered therapeutic hypothermia by unit level of care. (a) Includes items 5–10, and combined items 1–2 and 3–4. (b) Includes items 12–14, 17, 21, 22. (c) Includes items 20, 25, 27–30, and combined items 24a–24b, 26a–26d and 26b–26c. Total=(a)+(b)+(c). The data for the items regarding “Delivery”, “6h life” and “Delivery-6h life” include the answers of all 89 hospitals. The data for items regarding “Professionals” and for the “Total” questionnaire include the responses of the 53 hospitals that offered TH that participated in the survey (4 level IIIA, 34 level IIIB and 15 level IIIC).

In NBs with perinatal asphyxia, the first 6h of life constitute a crucial window in which care involves different stages from birth to the moment TH is initiated: (1) resuscitation and stabilisation of the patient, (2) control of comorbid factors, (3) accurate assessment of HIE severity, and (4) urgent transport to referral hospitals offering integral care for these newborns, including TH.2,6–8,12–14 The data obtained in our study indicate that the care of NBs with perinatal asphyxia, broken down into each of the stages of care comprised in the first 6h of life, is satisfactory overall, although we found differences in quality based on the level of care or whether the hospital provided TH.

Resuscitation and stabilisation in the delivery roomIn Spain, all neonatal units in tertiary care hospitals have specific protocols for the resuscitation and stabilisation in the delivery room of NBs that exhibit signs of perinatal asphyxia. In adherence with current recommendations, these hospitals have staff specifically trained on neonatal resuscitation and avoid the administration of calcium and sodium bicarbonate.15,16 They also report turning off the radiant heat of the incubator once the NB has stabilised after resuscitation. While current guidelines call for preventing hyperthermia and initiating TH in NBs with moderate to severe HIE, they do not specify the measures that should be initiated during resuscitation.16,17 In any case, given the usual decline in body temperature in NBs with asphyxia, monitoring the core temperature is a must in the delivery room, especially if external heat sources are withdrawn.18,19

After the initial stabilisation, monitoring of various physiological parameters, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory function and body temperature, is standard practice in the management of these patients. A point that remains controversial is whether NBs that recover quickly in the delivery room should be allowed to stay with their mothers to promote skin-to-skin contact and initiation of breastfeeding or, on the contrary, should be transferred to the neonatal unit for a period of monitoring, and enteral feeding delayed due to the potential risk of intestinal hypoperfusion. In our study, most hospitals reported admitting NBs with asphyxia to the neonatal unit, although 25% contemplated the possibility of having the NB remain with the mother if they recovered quickly and well.

Control of body temperatureA key aspect in the care of NBs with perinatal asphyxia is the control of body temperature from minutes after birth until the decision is made whether to use TH or not. For each 1°C increase in body temperature, there is an up to 4-fold increase in the odds ratio for death or moderate-to-severe neurologic impairment.20 Consistently with this knowledge, 98% of hospitals reported transferring the NB to the neonatal unit with the heat of the transport incubator off and monitoring the rectal temperature in the first hours of life to avoid excessive cooling and, more importantly, hyperthermia.21 In addition, most hospitals reported that they generally maintained body temperature below 36°C. At present, there is no evidence on the benefits or risks of lowering the body temperature below the normal range or even to the range of TH (33–34°C) in NBs with perinatal asphyxia before establishing the presence of moderate-to-severe HIE.

Control of comorbid factorsFollowing a hypoxic-ischaemic insult, the brain is particularly vulnerable to comorbid factors with the potential to damage the CNS, shorten the therapeutic window and increase the severity of the injury. These factors include hypoglycaemia, hypocarbia and hyperoxia or hypoxia.

Perinatal asphyxia is an important cause of hypoglycaemia due to the anaerobic metabolism of glucose. Furthermore, the concomitant presence of hypoxaemia and ischaemia may increase the vulnerability of the neonatal brain to hypoglycaemia. A blood glucose level of less than 40–46.8mg/dL in the early hours of life increases the risk of developing moderate-to-severe HIE22–25 and of subsequent death or neurologic impairment.24,25 All hospitals reported measuring blood glucose levels at least once and initiated fluid therapy at admission. There is no scientific evidence supporting the routine initiation of an intravenous dextrose infusion16 as opposed to monitoring blood glucose levels and initiating enteral feeding. In this regard, it is important to assess for the presence of acidosis or hyperlactatemia, which could be signs of poor intestinal perfusion.

Another universal practice across hospitals was measurement of blood gases in the first 6h of life with the purpose of detecting abnormalities such as severe hypocarbia (pCO2<20mmHg) or sustained moderate hypocarbia (pCO2, 20–25mmHg), which appear to carry an increased risk of death or moderate-to-severe neurologic impairment in NBs with HIE.26–28

Identification of newborns with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathyBesides monitoring vital signs and potential comorbid factors through laboratory tests, the most important task in the management of NBs with perinatal asphyxia is to determine whether the patient does or not have acute encephalopathy. Since this is a dynamic condition that may change with time and its diagnosis and severity are established based on clinical manifestations, it is recommended that several neurologic assessments be performed in the first 6h of life.2,3,7,13 Consistent with this, 90% of the hospitals reported that they usually performed 2 or more assessments. As an orientation for practice, 3h post birth could be a good time to determine the need for active hypothermia in a NB with perinatal asphyxia that exhibits moderate-to-severe HIE at this time point.5 If the decision were made to prescribe TH immediately after birth to pursue the maximum possible benefits, numerous NBs that would have recovered with a good outcome without treatment would be subjected to the latter. On the other hand, if initiation of TH were delayed past 6h post birth, the optimal benefit of treatment would not be achieved, as treatment is more effective the sooner it starts after the hypoxic-ischaemic insult.29,30

All hospitals reported using scales to assess the severity of encephalopathy, most frequently the scale proposed by García-Alix,10 followed by the scale proposed by Sarnat.11 These scales offer a standardised, systematic and organised approach to the assessment of severity, allowing homogeneous assessment by professionals with varying degrees of training in neurology as well as the comparison of patients classified into homogeneous groups. It would be beneficial for every hospital to become confident and experienced in the use of the same scale. While awaiting data from clinical trials in NBs with mild HIE, we ought to remember that at present TH is only indicated for treatment of NBs with moderate-to-severe HIE, although there are studies in the literature that have reported including 15–30% of NBs with mild HIE in the group treated with hypothermia.31–33

Abnormalities in electrocortical activity detected by aEEG have been used to determine the indication of TH in NBs with perinatal asphyxia34,35 and, more commonly, to monitor brain function during the acute phase of encephalopathy36 and detect silent seizures. Furthermore, the simplicity of its interpretation combined with its high predictive value makes aEEG extremely valuable in NBs with neurologic involvement, and particularly in NBs with HIE.35,36 We ought to highlight that 35% of the neonatal units reported not having access to aEEG, even though all of were Level III units and some were in hospitals that offered TH. This finding suggests an opportunity for improvement, as it does not seem possible to offer optimal care with TH to NBs without the information that can be obtained through aEEG monitoring.

While the data from the survey demonstrate an adequate quality of care, with similar scores in hospitals that offer TH versus those that do not, there is room for improvement, as only 50% of the 89 tertiary care hospitals delivered “optimal care.” We also found differences based on the level of care of the neonatal units and on whether they did or did not offer TH, with the quality of care in the delivery room and the 6h of life being higher in level IIIC and IIIB units that offered TH compared to level IIIA units, and the availability of experienced professionals being greater in level IIIC units compared to all others.

One key element in the improvement of the response within this narrow time frame is adequate training of paediatricians that manage deliveries such that they would be able to quickly identify newborns eligible for TH and activate the “hypothermia code” very early on.37 In Spain, the incidence of perinatal asphyxia is of approximately 7 cases per 1000 births,7 and while most newborns will not require transport, the activation of this code and the implementation of a sequence of actions that we call “brain neuroprotection chain” serve to put the transport team and referral hospital on alert, closely monitor the neurologic condition of the NB, control potential comorbid factors and identify the presence of HIE, all within the 6-hour “golden window” (Fig. 4). Our study has identified areas for improvement, such as technological resources and staff training; at minimum, all hospitals that offer TH should have aEEG equipment and neonatologists trained in the use of the various tools employed for neurologic assessment and with experience in the management of the complications associated with HIE.12,38

Protocol for care in the first 6h of life and the “brain neuroprotection chain.” aEEG, amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram; BD, base deficit; BP, arterial blood pressure; BS, burst suppression pattern; LV, low voltage pattern; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; FT, flat trace; GA, gestational age; HIE, hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy; HR, heart rate; hypoCa++, hypocalcaemia; hypoMg++, hypomagnesemia; RS, resuscitation; NB, newborn; RR, respiratory rate; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; rScO2: regional cerebral oxygen saturation; SatO2: arterial oxygen saturation; T, body temperature.

The main strength of this study is that practically every tertiary care hospital provided information, thanks to which we have unique data previously unknown that provide a global perspective of the management in Spain of NBs with perinatal asphyxia eligible for TH in the first hours of life. On the other hand, there are also limitations. The survey methodology carries risks of bias, as the dataset may have incomplete or inaccurate information. Since there are no validated criteria for the assessment of health care quality in the first 6h of life in the context of perinatal asphyxia, we rated clinical practices by comparing them to the recommendations of current clinical practice guidelines.2,3,12–14 Furthermore, we excluded the items that are most controversial from the rating, and chose to apply an asymmetrical rating scale to emphasise the value of acting in adherence to recommended standards in contrast to “rarely or never” doing so. Last of all, we ought to note that our survey assessed the general protocols established in each hospital, and thus could not provide information on the quality of the actual care delivered to patients.

The information contributed by our study is particularly relevant to shape care practices in Spain during the golden window in NBs with asphyxia at risk of HIE and has identified potential areas for improvement so that efforts can be targeted to deliver adequate care in this time frame.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank Sonia Arnáez for her collaboration in designing the icons of the Brain Neuroprotection Chain.

ESP-EHI Working Group. Neonatal units of tertiary hospitals in Spain.

J. Diez-Delgado (Torrecárdenas, Almería), I. Benavente (Puerta del Mar, Cádiz), I. Tofé (Reina Sofía, Córdoba), A.E. Jerez (S. Cecilio, Granada), J.A. Hurtado (Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), J.M. Ceballos (J.R. Jiménez, Huelva), M.L. Millán (C. Hospitalario, Jaén), M.D. Esquivel (Materno-Infantil, Jerez), C. Ruiz (Costa del Sol, Marbella), M. Baca (Quirón, Málaga), E. Tapia (G. Universitario, Málaga), M. Losada (Quirón S. Corazón, Sevilla), E. Torres (Valme, Sevilla), A. Pavón (Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla), P.J. Jiménez (Virgen Macarena, Sevilla), F. Jiménez (S. Ángela de la Cruz, Sevilla), M.P. Ventura (Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza), S. Rite (Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), T. González (Cabueñes, Gijón), R.P. Arias (Central Asturias, Oviedo), P.R. Balliu (Son Espases, Mallorca), J.M. Lloreda-García (S. Lucía, Cartagena), J.L. Alcaráz (Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia), C. Tapia (General, Alicante), A. de la Morena (S. Juan, Alicante), I. Centelles (General, Castellón), I. Güemes (Casa de Salud, Valencia), J. Estañ (Clinico, Valencia), A. Alberola (La Fé, Valencia), S. Aparici (Quirón, Valencia), R. López (Nisa_9 de Octubre, Valencia), J. Beceiro (Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares), B. García (General, Fuenlabrada), L. Martínez (General, Getafe), E. González (Severo Ochoa, Leganés), L. Arruza (Clínico S. Carlos, Madrid), M.D. Blanco (Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), M.T. Moral (12 de Octubre, Madrid), B. Arias (La Zarzuela, Madrid), F. Mar (Ruber I., Madrid), J. Jiménez (Sanitas_La Moraleja, Madrid), G. Romera (Montepríncipe, Madrid), A. Cuñarro (Alcorcón), C. Muñóz (Puerta de Hierro_Majadahonda, Madrid), F. Cabañas (H. U. Quirón Madrid), E. Valverde (La Paz, Madrid), R. Montero (Nisa_Pardo de Aravaca, Madrid), J.C. Tejedor (General, Móstoles), C. Santana (Materno Insular, Las Palmas), B. Reyes (Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife), S. Romero (N. S. de Candelaria, Tenerife), A. Orizaola (Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander), M. Baquero (General, Albacete), D. Hernández (General, Ciudad Real), A. Pantoja (Virgen de la Salud, Toledo), C. Vega (HUBU, Burgos), L. Castañón (CAULE, León), E.P. Gutiérrez (Universitario, Salamanca), M. Benito (Clínico, Valladolid), S. Caserío (Rio Hortega, Valladolid), G. Arca (Clínic, Barcelona), M.J. García (S. Creu i S. Pau, Barcelona), M.A. López-Vílchez (H. del Mar, Barcelona), L. Castells (General de Catalunya, Barcelona), M. Domingo (Parc Taulí, Sabadell), W. Coroleu (Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona), H. Boix (Vall d¿Hebrón, Barcelona), R. Porta (I. Dexeus_Quirón, Barcelona), A. García-Alix (S. Joan de Déu, Barcelona), S. Martínez-Nadal (SCIAS, Barcelona), E. Jiménez (Dr. J. Trueta, Girona), E. Sole (Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida), M. Albújar (Joan XXIII, Tarragona), E.M. Fernández (Infanta Cristina, Badajoz), A.R. Barrio (S. Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres), E. Piñán (Mérida), A. Avila-Alvarez (CHU A Coruña), M.E. Vázquez (Lucus Augusti, Lugo), N. Balado (CHU, Orense), P.A. Crespo (CHU, Pontevedra), M.L. Couce (Clínico, Santiago de Compostela), A. Concheiro-Guisán (Xeral, Vigo), I. Esteban (S. Pedro, Logroño), A. Lavilla (CH, Navarra), V. Alzina (C. Universidad de Navarra), A. Aguirre (Basurto, Bilbao), B. Loureiro (Cruces, Bilbao), I. Echániz (Quirón, Bilbao), M.D. Elorza (HU. Donostia, San Sebastián), A. Euba (HUA Txagorritxu, Vitoria).

The members of the ESP-EHI Working Group are presented in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Arnaez J, Garcia-Alix A, Calvo S, Lubián-López S, Grupo de Trabajo ESP-EHI. Care of the newborn with perinatal asphyxia candidate for therapeutic hypothermia during the first six hours of life in Spain. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89:211–221.