Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and its comorbidities have an impact on the social anxiety of children and adolescents, but there are practically no studies addressing this topic in adolescence. Our objective was to assess the degree of social anxiety and to analyse the presence of psychiatric comorbidities (PSCs) in adolescents with ADHD.

MethodologyWe conducted a cross-sectional observational study in patients aged 12–18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of ADHD (DSM-5). We collected data on the presence and type of PSCs and assessed social anxiety by means of the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A).

ResultsForty-six child and adolescent psychiatrists and paediatric neurologists participated in the study and recruited 234 patients. Of the total patients, 68.8% (159) were male and 31.2% (72) female, with a mean age in the sample of 14.9 years (95% CI, 14.6–15.1). The type of ADHD was combined type (C) in 51.7% (121), predominantly inattentive (PI) in 37.2% (87), and predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (PH) in 9% (21). Of all patients, 97.9% (229) received pharmacological therapy: 78.6% (184) methylphenidate, 15% (35) lisdexamfetamine and 4.3% (10) atomoxetine.We found PSCs in 50.4% of the patients (118), of which the most frequent were learning and communication disorders (20.1%, n=47) and anxiety disorders (19.2%, n=45). The patients scored significantly higher in the SAS-A compared to reference values in the healthy population. The scores in the SAS-A were less favourable in adolescents with the PI type compared to those with the PH type (P=.015). The presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder was associated with worst scores in SAS-A (P<.001) showing an increased social anxiety.

ConclusionAdolescents with ADHD classified as PI and those with comorbid anxiety had a higher degree of social anxiety as measured by the SAS-A. This psychological aspect must be identified and controlled in adolescents with ADHD to promote their social adaptation.

El trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH) y su comorbilidad repercuten en la ansiedad social de niños y adolescentes, no obstante, apenas hay estudios que aborden este tema en la adolescencia. El objetivo era evaluar el grado de ansiedad social y analizar la presencia de comorbilidades psiquiátricas (CPS).

MetodologíaEstudio observacional transversal en el que se incluyeron pacientes de 12-18 años con diagnóstico confirmado de TDAH (DSM-5). Se recogió información sobre la presencia y tipo de CPS y se evaluó la ansiedad social mediante la escala Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A).

ResultadosParticiparon 46 especialistas de psiquiatría del niño y del adolescente o neuropediatría, que incluyeron a 234 pacientes. El 68,8% (159) eran varones y el 31,2% (72) mujeres, con edad media de 14,9 años (IC 95%: 14,6-15,1). El 51,7% (121) tenía TDAH de tipo combinado (TC), el 37,2% (87) con predominio del déficit de atención (TDA) y el 9% (21) con predominio hiperactivo-impulsivo (TH). El 97,9% (229 pacientes) recibía tratamiento farmacológico: metilfenidato en el 78,6% (184), lisdexanfetamina en el 15% (35) y atomoxetina en el 4,3% (10).

El 50,4% (118) presentaba alguna CPS, con predominio de los trastornos del aprendizaje y de la comunicación (47, 20,1%) y los trastornos de ansiedad (45, 19,2%). Se observó un grado de ansiedad social significativamente mayor en comparación con los valores normales de la escala en la población sana. Los adolescentes con TDA presentaron peores puntuaciones en la escala SAS-A en comparación con adolescentes con TH (p=0,015). La presencia de trastornos de ansiedad comórbidos se relacionó con peores puntuaciones en la escala SAS-A, reflejando una mayor ansiedad social en estos pacientes (p<0,001).

ConclusionesLos adolescentes con diagnóstico de TDA y aquellos con comorbilidades psiquiátricas de tipo ansiedad presentaron un mayor grado de ansiedad social según su puntuación en la escala SAS-A. Este aspecto psicológico debería ser detectado y controlado en los adolescentes con TDAH para favorecer su adaptación social.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in childhood and one of the most extensively studied disorders in children, but few studies have been conducted in the adolescent population, which is why research in this age group is of great interest.1–3

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is one of the most frequent reasons for consultation in the fields of child psychiatry, paediatrics and paediatric neurology. The prevalence in Spain reported in different studies ranges from 1% or 2% to 14.4%.2 One of the characteristics of this disorder is the high prevalence of comorbidity,4 with 67%–80% of children and 80% of adults suffering an additional psychiatric disorder and 50% two or more.5 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder also increases the risk of comorbid disorders, especially in adolescence.6 The most frequent comorbidities are behavioural disorders, mood disorders and learning disorders, found in 30%.3

Comorbidity increases the severity of the clinical course and has an impact on the response to treatment, quality of life and social adaptation. The latter is particularly relevant in adolescence, when young individuals open to the world and define their personal identity. The degree in which comorbidity is associated with social anxiety in adolescents with ADHD is a subject that has not been addressed in the literature, and precisely the research focus of this study.

The presence of comorbidity and the type of ADHD experienced by the patient modifies the severity of disease, so it is of great interest to determine how ADHD is affected by specific comorbid disorders.

Due to the considerable weight of adolescence on the development of social functioning, further research on the psychosocial development of these patients is also needed.7 There are practically no studies assessing the degree of social anxiety in patients with ADHD specifically during adolescence, the time when social behaviour patterns develop, or on how it may change with treatment.8,9

The aim of the SELFIE study was to assess social anxiety in adolescents with ADHD in Spain by means of the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A), and to establish the pattern of psychiatric comorbidities and analyse the association between the presence of psychiatric comorbidities and social anxiety.10,11

Materials and methodsStudy design and ethical standardsWe conducted a cross-sectional observational study. The recruitment period went from February through October 2016. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Puerta de Hierro Hospital in Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain (03/16). All patients and the parents or legal guardians of those that were minors received information about the study and agreed to participate by signing the informed consent form. The study conformed to the ethical principles of the latest update of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Specialists from 46 child and adolescent psychiatry or paediatric neurology clinics in 30 provinces of 14 autonomous communities in Spain participated in the study.

RecruitmentThe sample was obtained by recruiting the first 5 patients that visited each clinic that met the inclusion criteria. We obtained the data from the health records of the patient and from the information collected during the visit in which the patient was included in the study.

Patients of any race and gender aged 12–18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on the DSM-5 criteria were included in the study.12

Sociodemographic and clinical variablesWe collected data on the year of birth, sex, weight, height, socioeconomic level (low, annual income <15000 euro; middle, annual income of 15000–45000 euro; high, annual income >45000 euro), alcohol use (>40g/day in male patients and >20g/day in female patients), tobacco use (daily consumption) and drug use (regular or occasional use). We also assessed the history of psychiatric disease or ADHD in first-degree relatives.

In regard to ADHD, we recorded the date of diagnosis and the type of ADHD diagnosed in the patient: predominantly inattentive (PI), predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (PH), or combined type (CT). We reviewed the health records of the patients following standard clinical procedure to collect information on the presence of psychiatric comorbidities (PSCs) based on the DSM-5 classification, the presence of non-psychiatric comorbidities based on the ICD-10 classification, and whether there was a past history of suicide attempts.

Clinical assessmentAdolescents were asked to complete the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A). This is a tool specifically designed for the evaluation of social anxiety.10,11

The SAS-A comprises 22 items, 18 of which are statements and 4 control questions, and the final score ranges between 18 and 90 points. Each item is answered on a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the extent to which the given statement “is true” for the respondent, with answer options ranging from 1 (“It is never true”) to 5 (“It is always true”). The SAS-A contains three subscales: fear of negative evaluation (FNE), with 8 items; social avoidance and distress in new situations (SAD-N), with 6 items; and social avoidance and distress experienced in general (SAD-G), with 4 items. Higher scores indicate greater severity.

TreatmentPatients did not receive treatment as part of the study, but received medical treatment and/or care for their disorder based on the clinical judgement of the specialist in charge. We collected data on the history of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments received prior to the study as well as current treatment.

Sample sizeThe primary endpoint of the study was the mean score on the SAS-A at the time of the visit, which were compared to reference scores obtained in the general healthy adolescent population. We estimated the mean reference value for the total score in the Spanish population at 43.17 points, with a standard deviation of 12.95. We calculated the sample size required to get a power of 100% in detecting significant differences greater than one standard deviation relative to reference values with an alpha of 0.05 (two-sided)10,11 using SPSS Sample Power, which was 234 patients.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis, calculating frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and the mean, 95% confidence interval, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum for quantitative variables. We compared qualitative variables by means of the Fisher exact test or the chi square test. We compared quantitative variables by the Student t test for independent samples as applicable. We performed factor analysis to assess differences in the SAS-A scores based on different factors, applying the Bonferroni or Games Howell correction based on the homogeneity of variance to control for errors in multiple comparisons. We performed exploratory multivariate analysis to assess the association between the total and subscale scores in the SAS-A and different control variables recorded in the study. We defined statistical significance as a P-value of less than .05. The analysis was performed with SPSS version 24.0.

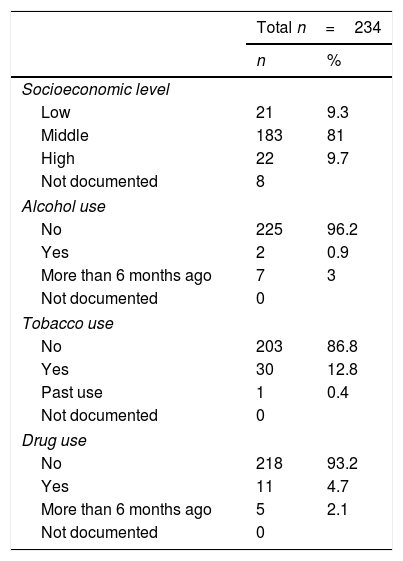

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics and medical historyThe study included a total of 234 adolescents. Of all patients, 68.8% (159) were male and 31.2% (72) female, while the sex was not recorded in 3. The mean age was 14.9 years (95% CI, 14.6–15.1), with no differences based on sex (P=.798). We found no differences between the sexes in body mass index (P=.705), with a mean of 21.2kg/m2 (95% CI, 20.7–21.7). Five patients (2.2%) had obesity (body mass index ≥30kg/m2). Table 1 presents the distribution of socioeconomic levels and substance use, with no differences based on sex.

Socio-economic level and substance use distribution in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

| Total n=234 | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Socioeconomic level | ||

| Low | 21 | 9.3 |

| Middle | 183 | 81 |

| High | 22 | 9.7 |

| Not documented | 8 | |

| Alcohol use | ||

| No | 225 | 96.2 |

| Yes | 2 | 0.9 |

| More than 6 months ago | 7 | 3 |

| Not documented | 0 | |

| Tobacco use | ||

| No | 203 | 86.8 |

| Yes | 30 | 12.8 |

| Past use | 1 | 0.4 |

| Not documented | 0 | |

| Drug use | ||

| No | 218 | 93.2 |

| Yes | 11 | 4.7 |

| More than 6 months ago | 5 | 2.1 |

| Not documented | 0 | |

There was a history of ADHD in first-degree relatives in 32.1% of the patients (75). Three patients (1.3%) had a history of suicide attempts, all of them female, two with PI type and one with combined ADHD.

Diagnosis of ADHDOf all patients, 51.7% (121) were classified as having combined ADHD, 37.2% (87) as having PI ADHD, and 9% (21) as having PH ADHD, while the type of ADHD had not been determined at the time of inclusion in the study in 2.1% (5). A higher proportion of female patients were in the PI group (48.6%, n=35) compared to male patients (32.1%; n=51) (P<.05).

We found no differences between male and female patients in the age of diagnosis of ADHD (P=.455). The mean age at diagnosis was 10.6 years (95% CI, 10.1–11), with a minimum of 3.1 and a maximum of 18 years. We found that ADHD was diagnosed significantly later in patients with the PI type compared to those with combined type (P=.022), with a mean difference of 1.4 years (95% CI 0.1–2.6), with no differences in relation to the other types of ADHD. The mean duration of ADHD was 4.2 years (95% CI, 3.8–4.7).

ComorbidityWe found non-psychiatric comorbidity in 24.8% patients (58).

Of all patients, 50.4% (118) had psychiatric comorbidities (PSCs). We found no significant differences in the prevalence of PSCs based on sex or ADHD type. Of all patients in the sample, 26.5% (62) had 2 or more PSCs. The mean number of PSCs was 1.9 (95% CI, 1.7–2.1), with a range of 1–6 PSCs.

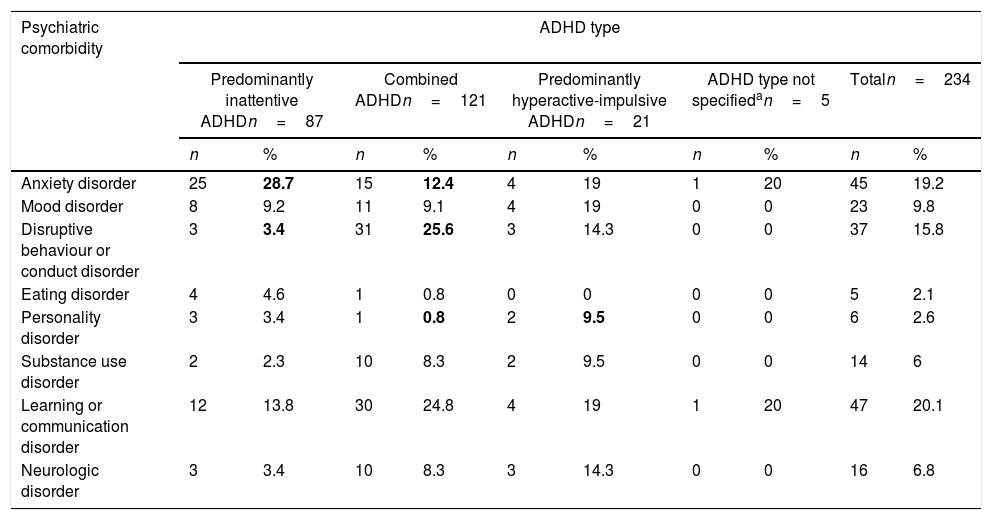

We present the frequency of each type of PSC by ADHD type in Table 2, where we used the DSM-IV classification to facilitate comparisons with previous studies. We found statistically significant differences in eating disorders (P=.017), which were more frequent in female adolescents. Anxiety disorders (P=.034) were more frequent in patients with PI type compared to those with CT. There was a higher proportion of behavioural disorders in patients with CT compared to patients with PI type (P<.001). Personality disorders were more frequent in patients with PH type compared to CT (P<.05).

Prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity (DSM-IV classification) by ADHD type.

| Psychiatric comorbidity | ADHD type | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predominantly inattentive ADHDn=87 | Combined ADHDn=121 | Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive ADHDn=21 | ADHD type not specifiedan=5 | Totaln=234 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Anxiety disorder | 25 | 28.7 | 15 | 12.4 | 4 | 19 | 1 | 20 | 45 | 19.2 |

| Mood disorder | 8 | 9.2 | 11 | 9.1 | 4 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 9.8 |

| Disruptive behaviour or conduct disorder | 3 | 3.4 | 31 | 25.6 | 3 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 15.8 |

| Eating disorder | 4 | 4.6 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2.1 |

| Personality disorder | 3 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2.6 |

| Substance use disorder | 2 | 2.3 | 10 | 8.3 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 6 |

| Learning or communication disorder | 12 | 13.8 | 30 | 24.8 | 4 | 19 | 1 | 20 | 47 | 20.1 |

| Neurologic disorder | 3 | 3.4 | 10 | 8.3 | 3 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 6.8 |

Statistically significant differences between ADHD groups in the frequency of specific disorders are presented in boldface.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

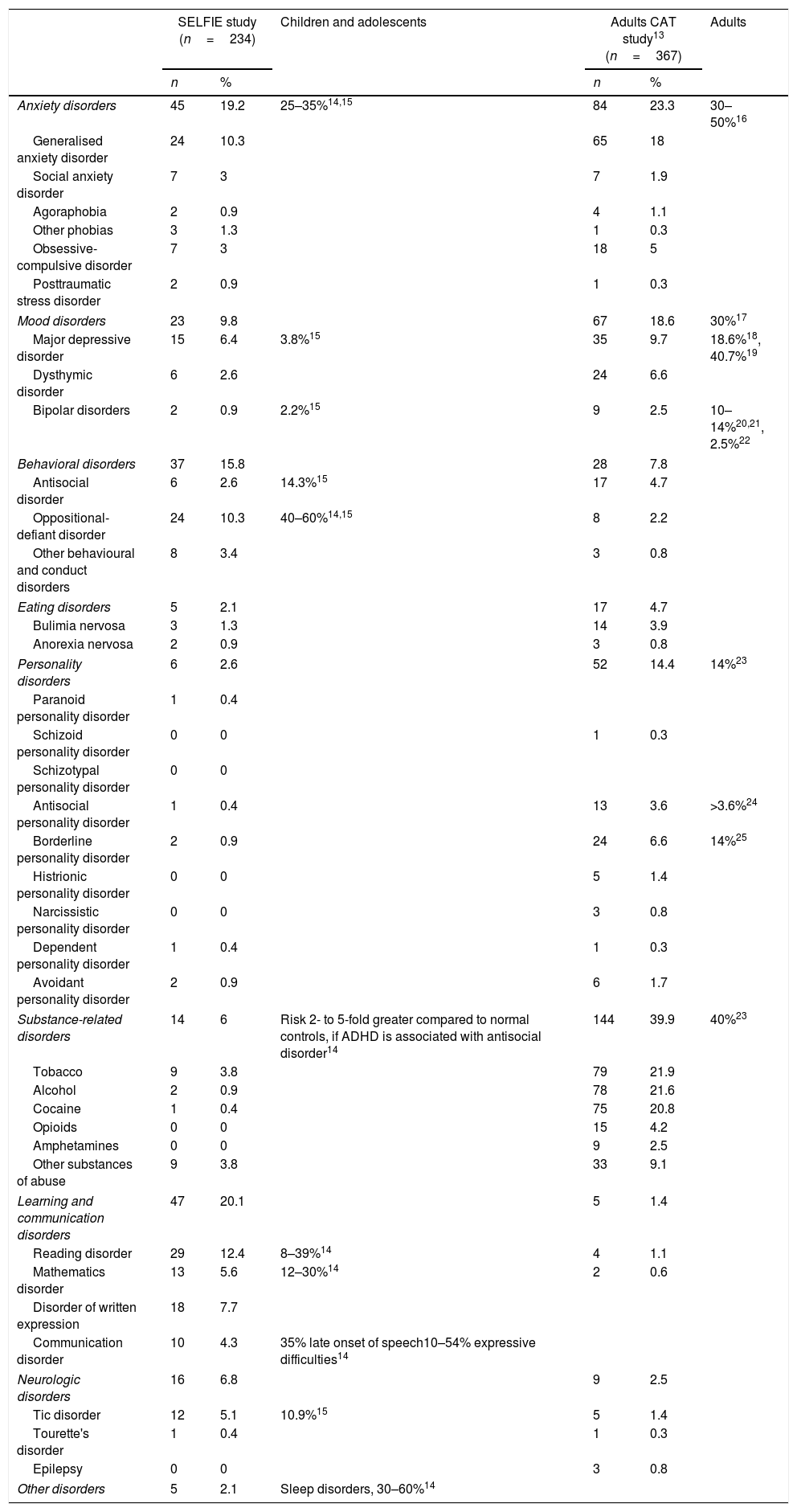

Table 3 details the PCSs observed in our study and compares their prevalence with the prevalence found in other studies.

Psychiatric comorbidities (DSM-IV classification), comparing the patients with ADHD in the SELFIE study with the results of other studies in children, adolescents and adults.

| SELFIE study (n=234) | Children and adolescents | Adults CAT study13 (n=367) | Adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Anxiety disorders | 45 | 19.2 | 25–35%14,15 | 84 | 23.3 | 30–50%16 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 24 | 10.3 | 65 | 18 | ||

| Social anxiety disorder | 7 | 3 | 7 | 1.9 | ||

| Agoraphobia | 2 | 0.9 | 4 | 1.1 | ||

| Other phobias | 3 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 7 | 3 | 18 | 5 | ||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 2 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Mood disorders | 23 | 9.8 | 67 | 18.6 | 30%17 | |

| Major depressive disorder | 15 | 6.4 | 3.8%15 | 35 | 9.7 | 18.6%18, 40.7%19 |

| Dysthymic disorder | 6 | 2.6 | 24 | 6.6 | ||

| Bipolar disorders | 2 | 0.9 | 2.2%15 | 9 | 2.5 | 10–14%20,21, 2.5%22 |

| Behavioral disorders | 37 | 15.8 | 28 | 7.8 | ||

| Antisocial disorder | 6 | 2.6 | 14.3%15 | 17 | 4.7 | |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder | 24 | 10.3 | 40–60%14,15 | 8 | 2.2 | |

| Other behavioural and conduct disorders | 8 | 3.4 | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Eating disorders | 5 | 2.1 | 17 | 4.7 | ||

| Bulimia nervosa | 3 | 1.3 | 14 | 3.9 | ||

| Anorexia nervosa | 2 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Personality disorders | 6 | 2.6 | 52 | 14.4 | 14%23 | |

| Paranoid personality disorder | 1 | 0.4 | ||||

| Schizoid personality disorder | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Antisocial personality disorder | 1 | 0.4 | 13 | 3.6 | >3.6%24 | |

| Borderline personality disorder | 2 | 0.9 | 24 | 6.6 | 14%25 | |

| Histrionic personality disorder | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.4 | ||

| Narcissistic personality disorder | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Dependent personality disorder | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Avoidant personality disorder | 2 | 0.9 | 6 | 1.7 | ||

| Substance-related disorders | 14 | 6 | Risk 2- to 5-fold greater compared to normal controls, if ADHD is associated with antisocial disorder14 | 144 | 39.9 | 40%23 |

| Tobacco | 9 | 3.8 | 79 | 21.9 | ||

| Alcohol | 2 | 0.9 | 78 | 21.6 | ||

| Cocaine | 1 | 0.4 | 75 | 20.8 | ||

| Opioids | 0 | 0 | 15 | 4.2 | ||

| Amphetamines | 0 | 0 | 9 | 2.5 | ||

| Other substances of abuse | 9 | 3.8 | 33 | 9.1 | ||

| Learning and communication disorders | 47 | 20.1 | 5 | 1.4 | ||

| Reading disorder | 29 | 12.4 | 8–39%14 | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Mathematics disorder | 13 | 5.6 | 12–30%14 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Disorder of written expression | 18 | 7.7 | ||||

| Communication disorder | 10 | 4.3 | 35% late onset of speech10–54% expressive difficulties14 | |||

| Neurologic disorders | 16 | 6.8 | 9 | 2.5 | ||

| Tic disorder | 12 | 5.1 | 10.9%15 | 5 | 1.4 | |

| Tourette's disorder | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Epilepsy | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Other disorders | 5 | 2.1 | Sleep disorders, 30–60%14 | |||

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Sixty-five percent of the patients (152) had received behavioural therapy, psychological support, or both, and these treatments were more frequent in patients with PSCs (78.8%, n=93) compared to patients without (50.9%, n=59) (P<.0001). In addition, 97.9% of patients (229) had received some type of pharmacological treatment prior to inclusion in the study.

The most frequent ongoing treatment for ADHD during the study was methylphenidate (184 patients, 78.6%), followed by lisdexamfetamine (35 patients, 15%) and atomoxetine (10 patients, 4.3%). A current treatment was not received in 5 patients.

Forty-two patients were receiving pharmacological treatment for PSCs, 36 with one drug, 4 with two drugs and 2 with three drugs. The drugs were risperidone (14), sertraline (9), fluoxetine (6), aripiprazole (5), paroxetine (5), topiramate (3), olanzapine (2), quetiapine (2), citalopram (1), escitalopram (1), lorazepam (1) and venlafaxine (1).

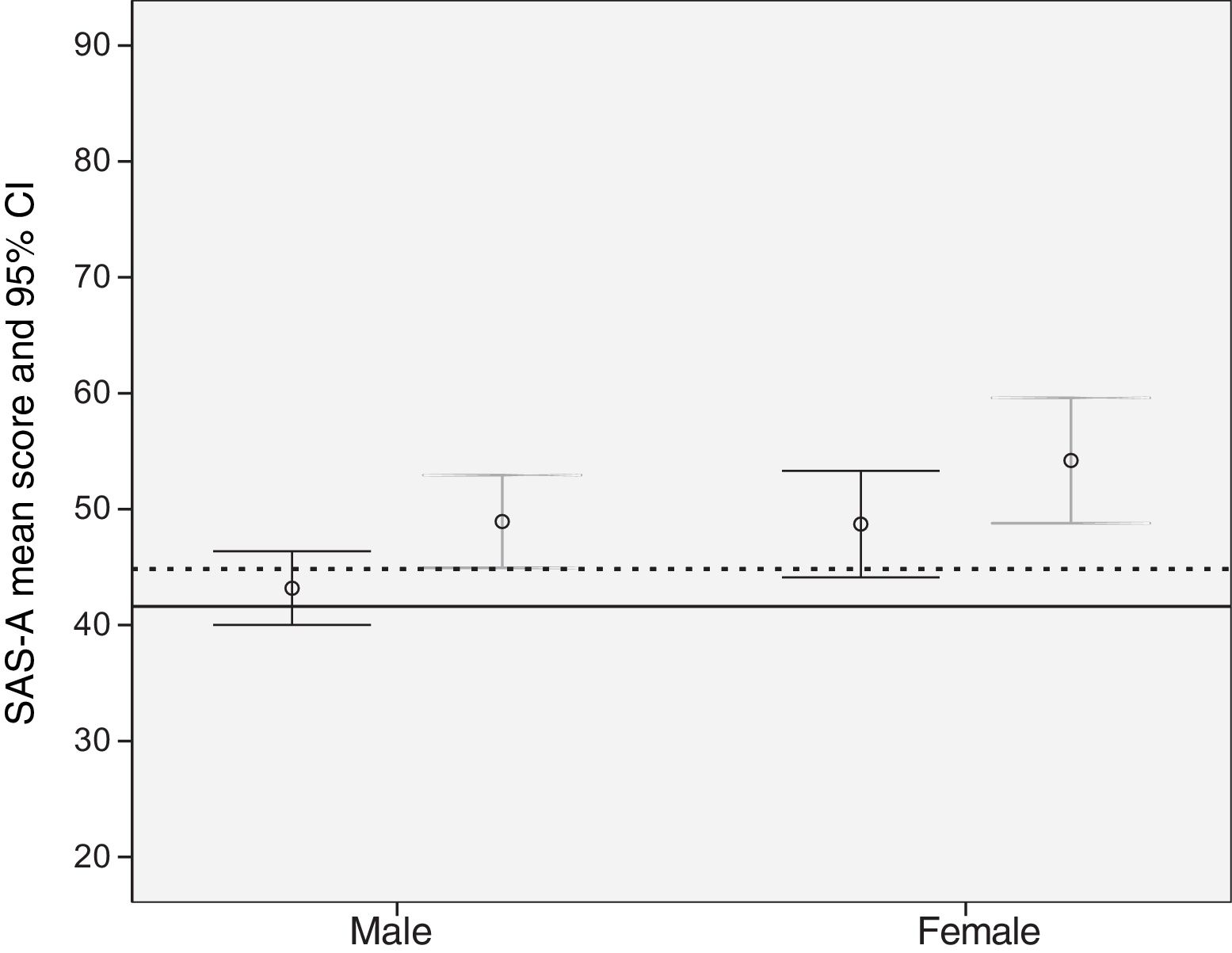

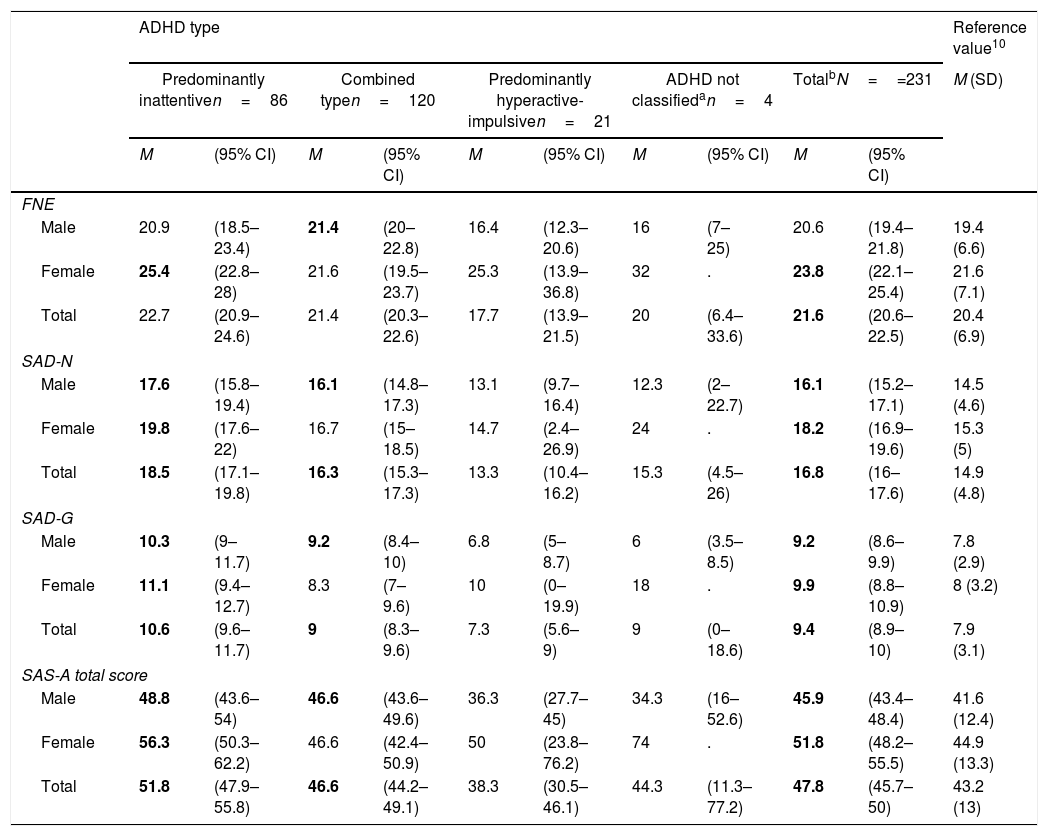

Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A)We compared SAS-A scores by sex and ADHD type and to reference values in the healthy adolescent population (Table 4). We found statistically significant differences between the sexes, with higher scores (greater severity) in female compared to male adolescents in the FNE subscale (P=.003), SAD-N subscale (P=.016) and the total score (P=.01).

SAS-A scores by sex and ADHD type compared to reference values from the healthy adolescent population in Spain.10

| ADHD type | Reference value10 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predominantly inattentiven=86 | Combined typen=120 | Predominantly hyperactive-impulsiven=21 | ADHD not classifiedan=4 | TotalbN==231 | M (SD) | ||||||

| M | (95% CI) | M | (95% CI) | M | (95% CI) | M | (95% CI) | M | (95% CI) | ||

| FNE | |||||||||||

| Male | 20.9 | (18.5–23.4) | 21.4 | (20–22.8) | 16.4 | (12.3–20.6) | 16 | (7–25) | 20.6 | (19.4–21.8) | 19.4 (6.6) |

| Female | 25.4 | (22.8–28) | 21.6 | (19.5–23.7) | 25.3 | (13.9–36.8) | 32 | . | 23.8 | (22.1–25.4) | 21.6 (7.1) |

| Total | 22.7 | (20.9–24.6) | 21.4 | (20.3–22.6) | 17.7 | (13.9–21.5) | 20 | (6.4–33.6) | 21.6 | (20.6–22.5) | 20.4 (6.9) |

| SAD-N | |||||||||||

| Male | 17.6 | (15.8–19.4) | 16.1 | (14.8–17.3) | 13.1 | (9.7–16.4) | 12.3 | (2–22.7) | 16.1 | (15.2–17.1) | 14.5 (4.6) |

| Female | 19.8 | (17.6–22) | 16.7 | (15–18.5) | 14.7 | (2.4–26.9) | 24 | . | 18.2 | (16.9–19.6) | 15.3 (5) |

| Total | 18.5 | (17.1–19.8) | 16.3 | (15.3–17.3) | 13.3 | (10.4–16.2) | 15.3 | (4.5–26) | 16.8 | (16–17.6) | 14.9 (4.8) |

| SAD-G | |||||||||||

| Male | 10.3 | (9–11.7) | 9.2 | (8.4–10) | 6.8 | (5–8.7) | 6 | (3.5–8.5) | 9.2 | (8.6–9.9) | 7.8 (2.9) |

| Female | 11.1 | (9.4–12.7) | 8.3 | (7–9.6) | 10 | (0–19.9) | 18 | . | 9.9 | (8.8–10.9) | 8 (3.2) |

| Total | 10.6 | (9.6–11.7) | 9 | (8.3–9.6) | 7.3 | (5.6–9) | 9 | (0–18.6) | 9.4 | (8.9–10) | 7.9 (3.1) |

| SAS-A total score | |||||||||||

| Male | 48.8 | (43.6–54) | 46.6 | (43.6–49.6) | 36.3 | (27.7–45) | 34.3 | (16–52.6) | 45.9 | (43.4–48.4) | 41.6 (12.4) |

| Female | 56.3 | (50.3–62.2) | 46.6 | (42.4–50.9) | 50 | (23.8–76.2) | 74 | . | 51.8 | (48.2–55.5) | 44.9 (13.3) |

| Total | 51.8 | (47.9–55.8) | 46.6 | (44.2–49.1) | 38.3 | (30.5–46.1) | 44.3 | (11.3–77.2) | 47.8 | (45.7–50) | 43.2 (13) |

We present statistically significant differences (P<.05) in bold face in the comparison with reference values in the last column.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CI, confidence interval; FNE, fear of negative evaluation subscale; M, mean; SAS-A, Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents; SAD-G, Social Avoidance and Distress experienced Generally/with acquaintances subscale; SAD-N, Social Avoidance and Distress in New situations/with strangers subscale; SD, standard deviation.

We found no differences in the FNE subscale scores based on the type of ADHD.

Scores were significantly higher on the SAD-N subscale in the PI group compared to the PH group (P=.003) and the CT group (P=.049).

Scores were significantly higher on the SAD-G subscale in the PI group compared to the PH group (P=.009) and the CT group (P=.045).

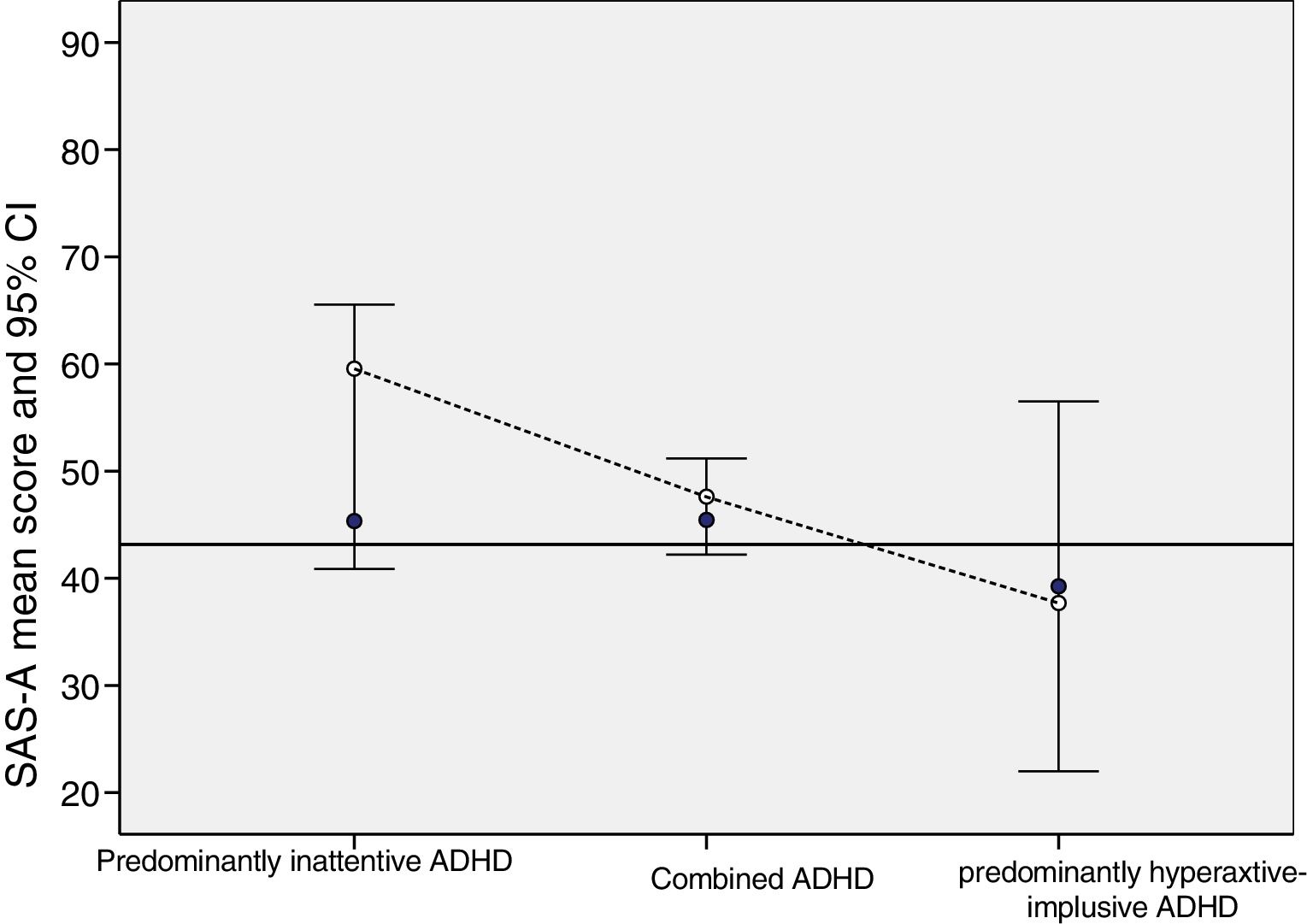

The total scores in the SAS-A were significantly higher in the PI group compared to the PH group (P=.003).

We assessed for differences in the total and subscale scores based on the treatment patients were receiving at the time of the study, and did not find any.

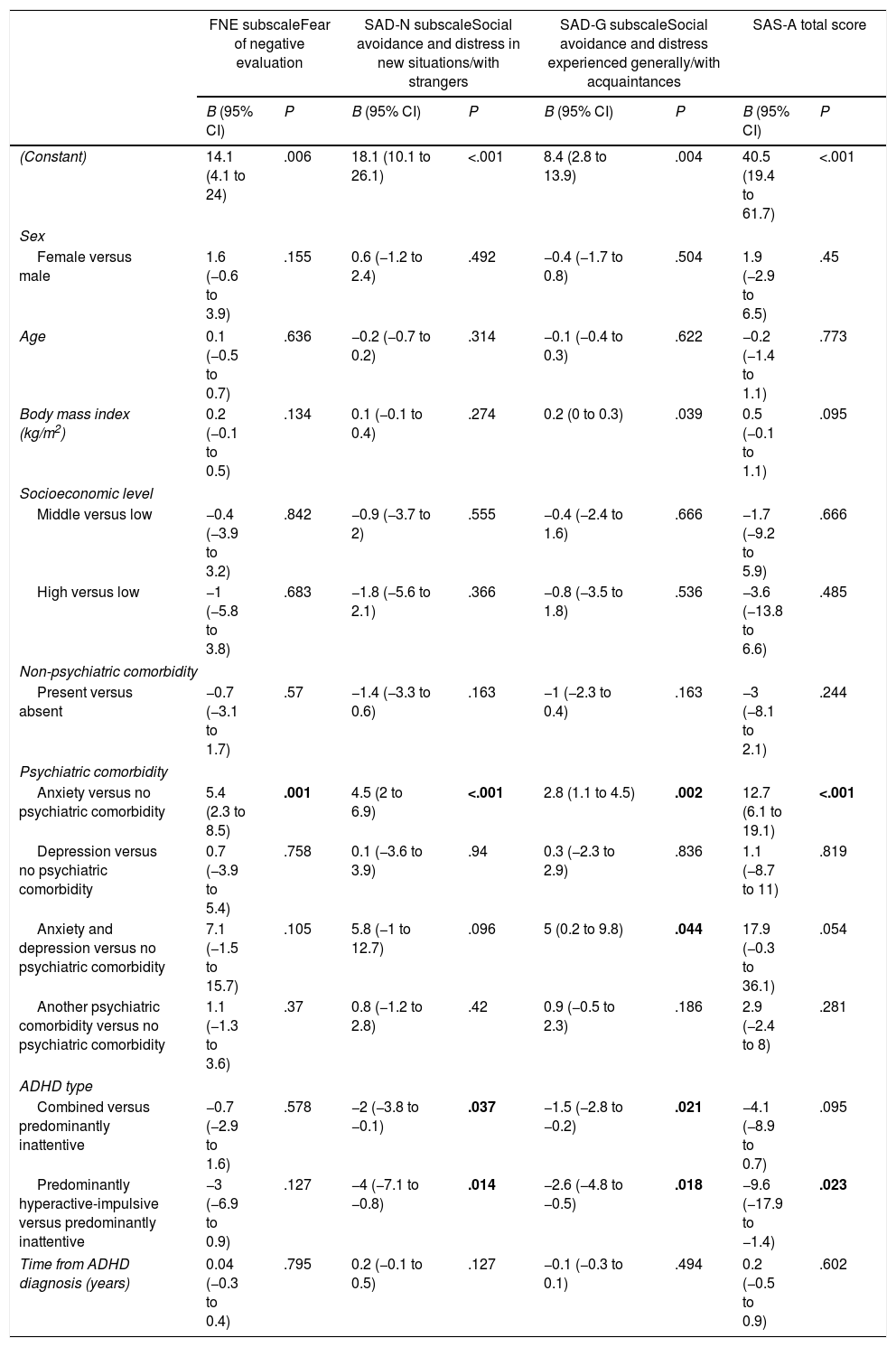

Table 5 presents the results of the exploratory multivariate analysis of the association between SAS-A total and subscale scores and the control variables, which included data for 204 patients. The equation explains only 15% of the variation (r2=0.151), so other factors that were not studied may have affected the results. In this analysis, we excluded obsessive-compulsive disorder from the group of anxiety PSCs, as this disorder is no longer included in the anxiety disorders in the DSM-5 classification. When it came to PSCs, we found the least favourable total scale and subscale scores in the SAS-A in adolescents with ADHD and a comorbid anxiety disorder compared those without PSCs (P<.01) independently of other variables. As for ADHD type, the group that scored least favourably in the total scale (P=.023) and SAD-N (P=.014) and SAD-G (P=.018) subscales was the PI group compared to the PH group. We also found that patients in the PI group scored higher in the SAD-N (P=.037) and SAD-G (P=.021) subscales compared to patients with the combined type, independently of other variables.

Multivariate linear regression analysis of factors related to SAS-A total score and subscale scores in ADHD adolescents.

| FNE subscaleFear of negative evaluation | SAD-N subscaleSocial avoidance and distress in new situations/with strangers | SAD-G subscaleSocial avoidance and distress experienced generally/with acquaintances | SAS-A total score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | P | B (95% CI) | P | B (95% CI) | P | B (95% CI) | P | |

| (Constant) | 14.1 (4.1 to 24) | .006 | 18.1 (10.1 to 26.1) | <.001 | 8.4 (2.8 to 13.9) | .004 | 40.5 (19.4 to 61.7) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female versus male | 1.6 (−0.6 to 3.9) | .155 | 0.6 (−1.2 to 2.4) | .492 | −0.4 (−1.7 to 0.8) | .504 | 1.9 (−2.9 to 6.5) | .45 |

| Age | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) | .636 | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.2) | .314 | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.3) | .622 | −0.2 (−1.4 to 1.1) | .773 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | .134 | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) | .274 | 0.2 (0 to 0.3) | .039 | 0.5 (−0.1 to 1.1) | .095 |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||||||

| Middle versus low | −0.4 (−3.9 to 3.2) | .842 | −0.9 (−3.7 to 2) | .555 | −0.4 (−2.4 to 1.6) | .666 | −1.7 (−9.2 to 5.9) | .666 |

| High versus low | −1 (−5.8 to 3.8) | .683 | −1.8 (−5.6 to 2.1) | .366 | −0.8 (−3.5 to 1.8) | .536 | −3.6 (−13.8 to 6.6) | .485 |

| Non-psychiatric comorbidity | ||||||||

| Present versus absent | −0.7 (−3.1 to 1.7) | .57 | −1.4 (−3.3 to 0.6) | .163 | −1 (−2.3 to 0.4) | .163 | −3 (−8.1 to 2.1) | .244 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | ||||||||

| Anxiety versus no psychiatric comorbidity | 5.4 (2.3 to 8.5) | .001 | 4.5 (2 to 6.9) | <.001 | 2.8 (1.1 to 4.5) | .002 | 12.7 (6.1 to 19.1) | <.001 |

| Depression versus no psychiatric comorbidity | 0.7 (−3.9 to 5.4) | .758 | 0.1 (−3.6 to 3.9) | .94 | 0.3 (−2.3 to 2.9) | .836 | 1.1 (−8.7 to 11) | .819 |

| Anxiety and depression versus no psychiatric comorbidity | 7.1 (−1.5 to 15.7) | .105 | 5.8 (−1 to 12.7) | .096 | 5 (0.2 to 9.8) | .044 | 17.9 (−0.3 to 36.1) | .054 |

| Another psychiatric comorbidity versus no psychiatric comorbidity | 1.1 (−1.3 to 3.6) | .37 | 0.8 (−1.2 to 2.8) | .42 | 0.9 (−0.5 to 2.3) | .186 | 2.9 (−2.4 to 8) | .281 |

| ADHD type | ||||||||

| Combined versus predominantly inattentive | −0.7 (−2.9 to 1.6) | .578 | −2 (−3.8 to −0.1) | .037 | −1.5 (−2.8 to −0.2) | .021 | −4.1 (−8.9 to 0.7) | .095 |

| Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive versus predominantly inattentive | −3 (−6.9 to 0.9) | .127 | −4 (−7.1 to −0.8) | .014 | −2.6 (−4.8 to −0.5) | .018 | −9.6 (−17.9 to −1.4) | .023 |

| Time from ADHD diagnosis (years) | 0.04 (−0.3 to 0.4) | .795 | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | .127 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | .494 | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.9) | .602 |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; SAS-A, Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents.

Statistically significant differences are presented in boldface.

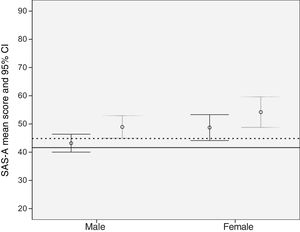

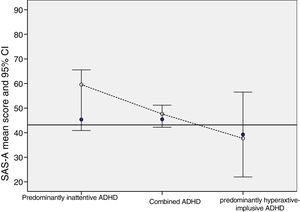

We compared the total scores in the SAS-A and the presence of psychiatric comorbidity by sex (Fig. 1) and by type of ADHD (Fig. 2) to reference values in the healthy adolescent population in Spain.10 On average, patients in our sample scored significantly higher compared to healthy Spanish adolescents. These differences were greater in patients with PSCs and in female patients. We found the greatest differences in the SAS-A scores relative to the reference population in patients with PI type and PSCs (Fig. 2).

Total score in the SAS-A in adolescents with ADHD, by sex and by presence or absence of psychiatric comorbidity, compared to the reference value in the healthy adolescent population in Spain.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; SAS-A, Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents.

The presence of psychiatric comorbidity is represented in grey, and its absence in black.

Reference values in the healthy adolescent population are shown as a continuous horizontal line for male adolescents and a dotted horizontal line for female adolescents.10

Total score in the SAS-A in adolescents with ADHD, by ADHD type and by presence or absence of psychiatric comorbidity, compared to the reference value in the healthy adolescent population in Spain (black horizontal line).10

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; SAS-A, Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents.

Presence of psychiatric comorbidity: white circles; absence of psychiatric comorbidity: blue circles.

According to a systematic review of studies conducted worldwide, the prevalence rate of ADHD in children and adolescents is 5%, with no variations in the last three decades.26 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is more common in boys than in girls, with a sex ratio that ranges from 2.5:1 to 5.6:1,2 and, in the case of our study, of 2.2:1. The most common type is the combined type, and while the PI type is most common in female patients, patterns that we also found in our study.27

The mean age at onset of the initial symptoms is 4 to 5 years of age, but ADHD is usually not diagnosed until primary school, when children exhibit poor academic performance. On average, nearly six years elapse from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis of ADHD.2 In our study, the mean age at diagnosis was 10.6 years, which is consistent with the age reported in other studies.1–3 The literature shows that 85%–87% of children with ADHD have a psychiatric comorbidity, and 60% two comorbidities.28,29 In our study, 50.4% had one psychiatric comorbidity, and 26.5% had more than one psychiatric disorder, so our findings differed from those of previous studies on this aspect.

Oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety and antisocial disorder are the most frequent comorbidities based on the current literature. Low self-esteem and poor social skills are common features in adolescents and adults. Patients with ADHD also start using substances earlier and their risk of developing antisocial personality disorder is 5 times that of the general population.28,29

Some studies have reported different comorbidity patterns based on sex, with oppositional defiant disorder, behavioural disorders and major depression predominating in male patients, with a higher risk of anxiety disorders in female patients.29 However, there is also evidence that these differences disappear after puberty.30 In our study, we found no differences in the prevalence of PSCs based on sex. It is worth noting that we found different patterns of comorbidity based on the type of ADHD (Table 2), with a higher frequency of anxiety disorders in the PI group compared to the CT group, and a higher frequency of behavioural disorders in the CT group versus the PI group. We also found that personality disorders were more frequent in the PH group compared to the CT group. Thus, the prevalence of anxiety disorders is greater in the PI group, while behavioural disorders are more common in the CT group. Given that the PI type is more prevalent in female patients, they have a higher risk of suffering anxiety disorders, something that is also the case in the general female population.10 Based on the DSM-5 criteria, the only personality disorders that can be diagnosed before age 18 are borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. In our sample, 4 patients aged 18 years and 2 patients aged 17 and 16 years had received a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. We found that the alcohol consumption reported in our study was low compared to other studies, which may be due to underreporting by our patients.

Prospective longitudinal studies show that hyperactive and impulsive behaviours increase the risk of dysfunction in adolescence and are associated with a higher probability of oppositional defiant disorder,31 antisocial behaviour, personality disorders and substance abuse.32–38

The most frequent comorbid psychiatric disorders in adulthood are major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders and personality disorders, with a high prevalence of antisocial behaviour and substance abuse and lower grade point averages and vocabulary and reading scores.39 Learning and communication disorders and anxiety disorders, which prevail in childhood and adolescence (Table 3), give way to a predominance of substance-related, anxiety, mood and personality disorders in adulthood. The SELFIE study found a lower prevalence of PSCs in general, with a lower prevalence of anxiety disorders and behavioural and neurologic disorders and a higher prevalence of major depressive disorder. This is probably due to differences between countries and to the fact that some of the patients were diagnosed by psychiatrists and others by paediatric neurologists, among other factors.

To date, no studies have been conducted to assess the presence of comorbidities in patients that have received adequate treatment for ADHD diagnosed in childhood, so it is not known whether PSCs are less frequent in this group.

The findings of the SELFIE study (Tables 4 and 5) suggest that ADHD adolescents have greater social anxiety compared to the healthy population based on the results of the SAS-A. Our female patients exhibited more severe social anxiety, which is consistent with the greater anxiety found in female adolescents in the general population, although this association was not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. We found a significant association between higher scores in the SAS-A and the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders as well as the type of ADHD (Table 5). Thus, the PI group exhibited the highest levels of social anxiety on all subscales and on the total score of the SAS-A, with differences of up to 9.6 points compared to the PH group (Table 5, Fig. 2), while we found differences of up to 12.7 points in patients with psychiatric comorbidity, irrespective of ADHD type (Table 5, Fig. 1).

The limitations of the study are those intrinsic to its observational and cross-sectional design and to the selection of patients, as we did not collect any information on excluded patients, which may have resulted in exclusion of more severe cases, a possibility that could explain the lower prevalence of PCSs found in our study. The regression model explained a very small part of the variation, so it may be of interest to explain factors that we did not assess in future studies, such as a family history of anxiety disorders, perinatal anxiety risk factors, other social factors, etc.

As conclusion, predominantly inattentive ADHD is associated with a higher risk of social anxiety, a disorder that should be monitored in this group of patients. Social anxiety greatly influences the way in which children and adolescents interact with the surrounding environment and react to it, and therefore can contribute to the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Social anxiety detected by the SAS-A questionnaire is not diagnostic of an anxiety disorder, but detecting it is important, as it can contribute to the secondary prevention of future comorbidities that could lead to less favourable outcomes of these stage of development in patients with ADHD.40

FundingLaboratorios ROVI, S.A. funded the study.

conflicts of interestLaboratorios Farmacéuticos ROVI, S.A. funded the study.

María Jesús Mardomingo received a fee from Laboratorios Farmacéuticos ROVI, S.A. to coordinate the study.

Carlos Sancho is an employee of Laboratorios Farmacéuticos ROVI, S.A.

Begoña Soler was hired by Laboratorios Farmacéuticos ROVI to design the study, conduct the followup, perform the statistical analysis and manage related publications.

We thank the following researchers for their participation in the study: Appendix A. SELFIE study group.

Patricia Alcindor Huelva; Luis Artiles Pérez; Joan Bastardas Sardan; Oscar Blanco Barca; Cristina Casal Pena; José Casas Rivero; Rafael De Burgos Marín; Teresa De Santos Moreno; Oscar Durán Forteza; Alberto Fernández Jaén; Ingrid Filippidis Semino; David Fraguas Herráez; Fidel J. García Sánchez; Jorge Miguel García Téllez; José Antonio Gómez Sánchez; Balma Gómez Vicente; Montserrat Hernández Martínez; Abigail Huertas Patón; María Luisa Joga Elvira; Francisco José Lara Cabeza; María Jesús Luna Ibáñez; Marcos Madruga Garrido; Ignacio Málaga Dieguez; Claudia Matos Spohring; Sacramento Mayoral Moyano; José A. Mazaira Castro; Ricardo Alberto Migliorelli Toppi; Leonor Montoliu Tamarit; José Juan Muro Romero; Enrique Ortega García; Carmen Ortiz de Zárate Aguirresarube; Tamara Pablos Sánchez; Alfonso Pavón Puey; Beatriz Payá Gonzaléz; José Carlos Peláez; Iván Pérez Eguiagaray; Benjamín Piñeiro Dieguez; Eloy Rodriguez Arrebola; Andrés Rodríguez Sacristán Cascajo; Helena Romero Escobar; Javier Royo Moya; María José Ruiz Lozano; María Angustias Salmerón Ruiz; Carmen Sánchez García del Castillo; Joaquín María Sole Montserrat; Rosario Vacas Moreira; Magdalena Valverde Gómez

The names of the components of the SELFIE study group are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Mardomingo Sanz MJ, Sancho Mateo C, Soler López B, en representación del grupo de investigación del estudio SELFIE. Evaluación de la comorbilidad y la ansiedad social en adolescentes con trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad: Estudio SELFIE. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90:349–361.