The effectiveness of antenatal corticosteroid therapy for foetal lung maturation in pre-term infants is well known, but there is uncertainty about the time that the treatment remains effective. A descriptive, longitudinal study was conducted to determine whether the need for surfactant administration was determined by the time-lapse between corticosteroids administration and delivery, and when repeating the doses of maternal corticosteroids should be considered. A total of 91 premature infants ≤32 weeks and/or ≤1500g (limit 34+6 weeks) whose mothers had received a complete course of corticosteroids were included. In patients at 27–34+6 weeks, we found that the longer the time elapsed between delivery and administration of corticosteroids, the more likely the babies were to require treatment with surfactant (p=0.027). The resulting ROC curve determined an 8-days cut-off after which repeating a dose of corticosteroids should be assessed.

Aunque se conoce la efectividad de la corticoterapia materna para la maduración pulmonar foetal en prematuros, no hay seguridad acerca del tiempo en que el tratamiento continúa siendo efectivo. Realizamos un estudio descriptivo y longitudinal, para relacionar el tiempo transcurrido desde la administración de glucocorticoides maternos, y la necesidad o no de surfactante, y a partir de qué punto se debería considerar la repetición de las dosis de corticoides maternos. Se incluyeron 91 prematuros de ≤32 semanas y/o ≤1.500g (límite 34+6 semanas) cuyas madres habían recibido una pauta completa de corticoides. En los pacientes de 27-34+6 semanas, comprobamos que a mayor tiempo transcurrido entre el parto y la administración de corticoides, mayor probabilidad de necesitar tratamiento con surfactante (p=0,027). La curva ROC calculada determinó un punto de corte de 8 días a partir del cual debería valorarse el repetir la dosis de corticoide.

One of the greatest challenges for the neonatologist is the respiratory management of preterm infants (PTIs), with respiratory distress syndrome being the main disease in the field. Administration of antenatal corticosteroids in women at risk of preterm delivery and for gestational ages ≤34 weeks is indicated to prevent this condition.1,2 It has been demonstrated that a single complete course of antenatal corticosteroids (IM administration of 2 doses of 12mg of betamethasone each 24h) reduces neonatal mortality and severe morbidity with no long-term side effects.1,3,4

Until the year 2000, weekly rescue courses of corticosteroids were administered until delivery because maximum benefits were obtained between 24h and 7 days following administration of the last dose.5 That year, the panel of the Consensus Development Conference of the National Institutes of Health of the United States concluded that there were insufficient data to justify repeat courses of corticosteroids.6 Since then, several randomised clinical trials have been conducted that prove the effectiveness of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in promoting foetal lung maturation, but it is uncertain how long the treatment remains effective.7–10

The 2012 Cochrane Review1 indicates that given the short-term benefits of repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids, this treatment should be considered in women who have received a course of corticosteroids 7 or more days previously and who are at risk of preterm birth (≤34 weeks). Along these lines, the Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, SEGO) recommends the administration of antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at risk of preterm birth between weeks 24 and 34+6, and a repeat course if the clinical diagnosis of preterm risk persists or recurs.11

MethodsWe performed a retrospective, longitudinal descriptive study of PTIs born in our hospital between January 2008 and December 2011 to analyse the relationship between the time elapsed between corticosteroid administration to the mother and delivery, and the need for endotracheal surfactant treatment. We also sought to establish the moment from which repeat administration of antenatal corticosteroids should be considered when the risk of preterm birth remains.

The inclusion criteria were PTIs≤32 weeks and/or ≤1500g (age limit 34+6 weeks for low birth weight infants), whose mothers had received a complete course of corticosteroids to promote foetal lung maturation.

For each patient, we collected data on their sex, birth weight, gestational age, administration of antenatal corticosteroids, time elapsed between the last dose of corticosteroids and delivery, need for surfactant therapy, number of surfactant doses, need for budesonide at discharge, and death.

We did the statistical analysis with the SPSS® software version 20, using Student's t-test, the Mann–Whitney U test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, ANOVA, and the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare quantitative data; Pearson's χ2 test for qualitative data; and a multiple logistic regression model to plot prediction curves.

ResultsDuring the 4 years of the study, 144 infants (82 boys and 62 girls) with gestational ages ≤32 weeks and/or a birth weight ≤1500g (gestational age ≤34+6 weeks) were born in our centre. The mean gestational age was 29.33±2.58 weeks and the mean birth weight was 1150±280g; 91 patients (63%) were exposed to a complete course of antenatal corticosteroids to promote foetal lung maturation, 21 (15%) to an incomplete course, and 32 (22%) were unexposed. The main descriptive characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample.

| N (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 82 (57) |

| Female | 62 (43) |

| Multiple pregnancy | |

| One foetus | 95 (66) |

| 2 foetuses | 17 (24) |

| 3 foetuses | 5 (10) |

| Lung maturation | |

| Complete course (2 doses) | 91 (63) |

| Incomplete course (1 dose) | 21 (15) |

| No treatment for lung maturation | 32 (22) |

| Surfactant | |

| Yes | 81 (56) |

| No | 63 (44) |

| Number of surfactant doses | |

| 0 doses | 63 (44) |

| 1 dose | 59 (41) |

| 2 doses | 16 (11) |

| 3 doses | 4 (3) |

| 4 doses | 2 (1) |

| Budesonide prescription at discharge | |

| Yes | 19 (13) |

| No | 102 (71) |

| Death | 23 (16) |

Out of the 91 patients exposed to a complete course of corticosteroids, 45 were treated with surfactant and 46 were not. The distribution of these patients by birth weight and gestational age is shown in Table 2.

Patients who received a full course of lung maturation treatment. Distribution by gestational age, birth weight, and the need for endotracheal surfactant administration.

| Sex | Received surfactant (45 patients)18 girls and 27 boys | Did not receive surfactant (46 patients)23 girls and 23 boys |

| Gestational age | ||

| 24–26+6 | 19 | 1 |

| 27–29+6 | 22 | 12 |

| 30–31+6 | 4 | 16 |

| >32 weeks | 0 | 17 |

| Birth weight | ||

| ≤750g | 9 | 0 |

| 751–1000g | 13 | 3 |

| 1.001–1250g | 15 | 15 |

| 1251–1500g | 6 | 28 |

| >1500g | 2 | 0 |

When we compared the mean number of days elapsed since the administration of antenatal corticosteroids with the need for endotracheal surfactant treatment we found no significant differences (p=0.286). However, when we stratified the patients by gestational age we saw that there were no differences in the group aged ≤26+6 weeks, while in the 27–34+6 weeks group the probability of requiring surfactant treatment became higher (p=0.027) as the time elapsed between corticosteroid administration and delivery increased.

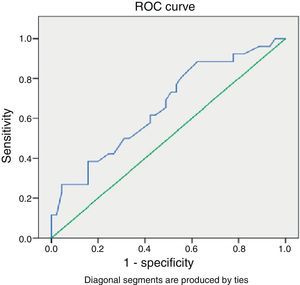

Looking at the group of patients with gestational ages 27–34+6 weeks, we found a ROC curve (Fig. 1) that determined a cut-off point of 8 days after which administration of a repeat course of corticosteroids should be considered if the risk of preterm birth remains. The sensitivity and specificity values for this point are 61% and 58%, respectively, with a 45% PPV and a 72% NPV.

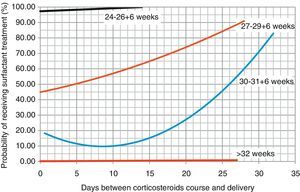

Based on these data, we proceeded to draw regression curves (Fig. 2) correlating the days elapsed from the administration of the course of corticosteroids for lung maturation, and the probability of receiving surfactant treatment (with the exception of the group with 24–26+6 weeks gestational age, where the results could not be analysed due to the low frequency of these patients in our sample).

When it came to requiring treatment with budesonide after discharge, 14 out of the 91 patients did require it, and we found no significant differences in this variable in relation to the time elapsed between corticosteroid administration and delivery (p=0.27). We also found no significant differences when we analysed the relationship between time-lapse between corticoids and delivery, and mortality (p=0.63).

DiscussionThe benefits of antenatal corticosteroids are extensively documented,7–10 but there are some controversies surrounding their use. One of them concerns the gestational age from which this treatment can really benefit the PTI. The 2006 Cochrane Review4 reported that the rates of respiratory distress decreased in every gestational age group except in the <26 weeks group, although only one study in the review included patients below that gestational age. In 2011 Onland et al. performed a meta-regression analysis of 9 randomised clinical trials and concluded that there was no significant decrease in neonatal morbidity and mortality in extreme preterm infants exposed to a course of corticosteroids,12 while other trials have shown a decrease in mortality among these patients.13 While our results for this group of patients were very limited due to the small sample size, we observed that the beneficial effect of corticosteroids became apparent once we stratified the patients and looked at patients with gestational ages between 27 and 34+6 weeks (p=0.027).

Another point of debate is whether women who have received a complete course of corticosteroids should or not receive repeat courses if the risk of preterm delivery persists. Randomised clinical trials offer contradictory results, as some support the administration of rescue doses after observing reduced neonatal morbidity,7,8 while others found no improvement in the outcomes of PTIs exposed to repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids.9,10

The potential side effects of exposure to antenatal corticosteroids include alterations in the development of the foetal brain and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, with potential repercussions in cognitive behaviour and on the cardiovascular and immune responses and adaptation to stress, risks that would increase with the administration of repeat doses.14,15 However, different studies have followed up PTIs exposed to repeat courses of antenatal corticosteroids to up to 6 years of age, and the cognitive skills of these patients do not differ from those of patients exposed to placebo.16–19 Stälnacke et al. followed PTIs exposed to 2–9 courses of antenatal corticosteroids to adolescence or adulthood, and found no differences in cognitive functions, attention, adaptability, or overall psychological function.2

The recommendation of the latest Cochrane Review and of the SEGO is to consider repeat doses of corticosteroids in women at risk of preterm delivery when 7 or more days have elapsed since the administration of the last dose.1,11 In our study, patients who were born more than 8 days after the administration of antenatal corticosteroids were at greater risk of requiring surfactant treatment, and the regression curves suggest that the probability of requiring surfactant treatment increases as more days elapse between corticoid administration and delivery, and that this effect is more marked the lower the gestational age.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Suárez O, García-Magán C, Saborido-Fiaño R, Pérez-Muñuzuri A, Baña-Souto A, Couce-Pico ML. Corticoides antenatales y prevención del distrés respiratorio del recién nacido prematuro: utilidad de la terapia de rescate. An Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:120–124.