This study was undertaken to estimate the burden of morbidity associated with laboratory-confirmed influenza in children below 15 years of age.

Patients and methodsChildren presenting with acute respiratory infection and/or isolated fever at the Basurto University Hospital, Bilbao, Spain between November 2010 and May 2011 were included in this study (NCT01592799). Two nasopharyngeal secretion samples were taken from each; one for a rapid influenza diagnostic test in the emergency department, and the second for laboratory analysis using real-time polymerase chain reaction and viral culture.

ResultsA total of 501 children were recruited, of whom 91 were hospitalized. Influenza diagnosis was confirmed in 131 children (26.1%); 120 of 410 (29.3%) treated as outpatients and 11 of 91 (12.1%) hospitalized children. A total of 370 of 501 children (73.9%) had no laboratory test positive for influenza. The proportion of subjects with other respiratory viruses was 145/501 (28.9%) cases and co-infection with the influenza virus plus another respiratory virus was detected in 7/501 (1.4%) cases. Influenza virus types were: A (H1N1 and H3N2) 53.2% (67/126); B (Victoria and Yamagata) 46.0% (58/126); A+B 0.8% (1/126). The median direct medical costs associated with each case of laboratory-confirmed influenza was €177.00 (N=131). No significant differences were observed between the medical costs associated with influenza A and B.

ConclusionAlmost half of the cases were influenza virus B type. The administration of a vaccine containing influenza A and B types to children below 15 years of age might reduce the overall burden of the illness.

El estudio se llevó a cabo para estimar la carga de enfermedad de la gripe confirmada por laboratorio en niños menores de 15 años.

Pacientes y métodosLos niños que acudieron al Hospital Universitario de Basurto con síntomas de infección respiratoria aguda y/o fiebre aislada entre noviembre de 2010 y mayo de 2011 fueron incluidos en el estudio (NCT01592799). Se tomaron 2muestras de secreción nasofaríngea: una para un test de diagnóstico rápido en el Servicio de Urgencias y otra para análisis en laboratorio con reacción en cadena de la polimerasa en tiempo real y cultivo viral.

ResultadosSe seleccionó a un total de 501 niños, de los que 91 fueron hospitalizados. El diagnóstico de gripe se confirmó en 131 (26,1%); 120/410 (29,3%) fueron tratados ambulatoriamente y 11/91 (12,1%), hospitalizados. En 370/501 niños (73,9%) el resultado no fue positivo. La proporción de otros virus respiratorios fue 145/501 (28,9%) casos y de coinfección con otro virus respiratorio además de gripe de 7/501 (1,4%). Los tipos de virus de gripe fueron: A (H1N1 y H3N2) 53,2% (67/126); B (Victoria y Yamagata) 46,0% (58/126); A+B 0,8% (1/126). El coste médico directo medio asociado con cada caso de gripe confirmada fue de 177,00€ (N=131). No se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre el coste asociado con gripe A o B.

ConclusiónCasi la mitad de los casos fueron virus de gripe B. La administración de una vacuna que incluya tipos A y B de gripe debería reducir la carga de la enfermedad.

Influenza, a highly contagious acute respiratory illness caused by the influenza virus, is associated with an extensive array of clinical symptoms, ranging from self-limiting respiratory conditions in the upper airways to systemic repercussions and potentially fatal complications.1,2 Influenza usually occurs in the form of annual epidemics, although it may occasionally give rise to a pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that influenza causes between three and five million cases globally each year; and accounts for approximately 300,000 deaths each season, of which more than 40,000 occur in the European Union.1,3 Breastfeeding infants, children with an underlying pathology and adults over 65 years of age are the most susceptible to the severe forms of the disease.2–4 However, the greatest morbidity is observed in pediatrics, and children represent the main transmitters of the infection. The disease in children is also associated with a substantial economic and social burden.4–6

The two most common types of influenza virus affecting humans are A and B. The annual influenza epidemics are usually caused by minor variants of both types,7 such that almost all children are infected in the first years of life and acquire protective immunity exclusively against that particular strain of virus. Since influenza A virus is capable of naturally infecting numerous animal species, it occasionally causes pandemics and generates greater concern among public health authorities than the influenza B virus, which only affects humans.2,8,9 As variation in influenza type A is wide, it is classified into sub-types, based on its HA (hemagglutinin) and NA (neuraminidase) membrane antigens. Antigenic and genetic differences have revealed two lineages of influenza B viruses: Victoria and Yamagata, which have circulated simultaneously around the globe since the 1980s.8,10 It is difficult to predict which lineage will dominate during the next influenza season.11

Vaccination against influenza is an effective way to prevent infection and its complications.4 Although it is difficult to know the real incidence of the illness due to the non-specific nature of symptoms,12 accurate data on the burden and medical costs associated with the illness are essential to develop the most appropriate vaccination policy. These data are limited in Spain, therefore this study was designed to quantify emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and the direct medical costs attributable to laboratory-confirmed influenza in children under 15 years of age that present to hospital with acute respiratory infection (ARI) and/or isolated fever during the influenza season.

Patients and methodsStudy design and populationThis prospective study (NCT01592799) was conducted at the Basurto University Hospital, Bilbao, Spain, a tertiary hospital with a general emergency service, between November 2010 and May 2011 (after the influenza pandemic of 2009), according to the principles of good clinical practice, the Declaration of Helsinki and local standards. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Board, and informed written consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of children below 12 years of age and from older children before inclusion.

Children under 15 years of age, presenting at the emergency department with ARI during an influenza season (defined as the period between the first and last cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza) were recruited, regardless of whether they were subsequently admitted to hospital. ARI was defined as the presence of at least one of the following symptoms: sore throat (in children≥3 years), rhinorrhea, cough and/or breathing difficulties, and/or isolated fever (oral temperature≥37.5°C/under-arm temperature≥37.5°C/rectal temperature≥38°C, eardrum temperature adjusted orally≥37.5°C/eardrum temperature adjusted rectally≥38°C).13

Two clinical specimens (throat swab and/or nasopharyngeal swab) were obtained from each patient and case medical histories were reviewed (including: previous vaccination details; concomitant medication; ARI and/or fever associated symptoms; findings on physical examination). Details were recorded directly by the attending pediatrician on the study clinical report form. For hospitalized children, information on the clinical course of the disease and administered treatment was completed at discharge.

Approximately one month after the initial visit to the hospital, families were contacted by telephone and a follow-up interview was conducted. Information concerning: the clinical course of the disease; requirement for further medical assistance; use of medication not prescribed at discharge; number of days absent from school and number of contacts in the household who subsequently developed influenza-like symptoms, were collected.

Using data on the hospital's administrative database, the medical costs associated with the influenza-like illness were calculated, including the cost of medical management in the emergency department, hospitalization, resources used for the diagnosis and treatment of the disease and any complications.

Laboratory proceduresIn order to rapidly identify influenza cases, a quick diagnostic test (Xpect Flu A&B, Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA) was performed immediately on one of the nasopharyngeal samples collected in the emergency department. Regardless of the result, all remaining samples were stored at 4°C and transported to the Valencian Microbiology Institute laboratory in a medium of Hank buffered saline solution (Hepes 1M buffer, 0.5% gelatin, 7.5% sodium bicarbonate, and antibiotics [penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B]) for confirmatory analysis using culture and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). For the latter determination, total RNA was extracted using the Maxwell 16 Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and amplified using multiplex RT-PCR sense and reverse primers, with double marked FAM-BHQ-1 or HEX-BHQ-1 probes to identify influenza types A14 and B,15 respectively.

Statistical analysesSample size estimation required the inclusion of 500 subjects attending the emergency department with ARI and/or isolated fever, based on an expected proportion of laboratory-confirmed influenza infection in 5–20% of subjects. The hospital collects medical costs of each treatment and care service that the patient receives. Direct medical costs for children with laboratory-confirmed influenza were calculated from the hospital's administrative data, taking into account: diagnostics, medical management and influenza treatment, visits to the emergency department, inpatient charge, ward specific room charge and intensive care unit (ICU) charge. The 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using Proc-StatXact (Cytel, Cambridge, MA, USA). Comparative tests between positive and negative influenza groups were carried out using Mann–Whitney tests for ordinal and continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables.

Additional exploratory analyses were performed to evaluate the direct medical costs, symptoms and the need for subsequent health-care assistance associated with influenza type A or B.

ResultsThere were 501 children recruited between November 2010 and April 2011. As sufficient data were available to allow the evaluation of all cases, all subjects were included in the final analysis. While 410 of the children were only seen at the emergency department, 91 children required hospitalization. Laboratory-confirmed influenza (using either rapid diagnostic test, culture or RT-PCR; all analysis performed for all subjects) was demonstrated in 26.1% of all children (131/501; 95% CI: 22.4–30.2); i.e., 29.3% of children attending only the emergency department (120/410; 95% CI: 24.9–33.9) and 12.1% of hospitalized cases (11/91; 95% CI: 6.2–20.6). The median age of children with laboratory-confirmed influenza was 36.0 months (range: 0–179 months) and 54.2% were male (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of children with laboratory-confirmed influenza (N=131).

| Characteristics | Parameters or categories | Laboratory-confirmed influenza Na=131 | Influenza type A n′b=67 | Influenza type B n′=58 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valuec or nd | %e | Value or n | % | Value or n | % | ||

| Age (months) | Median | 36.0 | – | 25.0 | – | 66.5 | – |

| Range | 0–179 | – | 0–153 | – | 1–179 | – | |

| Age group (months) | 0–5 | 17 | 13.0 | 14 | 20.9 | 3 | 5.2 |

| 6–23 | 26 | 19.8 | 19 | 28.4 | 5 | 8.6 | |

| 24–59 | 44 | 33.6 | 26 | 38.8 | 17 | 29.3 | |

| 60++ | 44 | 33.6 | 8 | 11.9 | 33 | 56.9 | |

| Gender | Female | 60 | 45.8 | 31 | 46.3 | 26 | 44.8 |

| Male | 71 | 54.2 | 36 | 53.7 | 32 | 55.2 | |

| History of influenza vaccination | 2007–2008 influenza season | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| 2008–2009 influenza season | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | – | 1 | 1.7 | |

| 2009–2010 influenza season | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |

| 2010–2011 influenza season | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |

Note: children with rapid test positive for type A and B are not considered.

Among 131 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza, laboratory tests indicated that 126 children were positive for influenza types A or B; 67 (53.2%) were positive for type A and 58 (46.0%) for type B; one child (0.8%) was positive for both types A and B. Results of the quantitative RT-PCR for influenza type A showed that around 87% had H1N1 subtype and 13% had H3N2 subtype. There were 370 of 501 children (73.9%) who did not test positive for influenza. Type B positive children were generally older than those infected by type A (Table 1). Among the children positive for influenza type B, the proportion of Victoria and Yamagata lineages were 96.6% (56/58) and 3.4% (2/58), respectively.

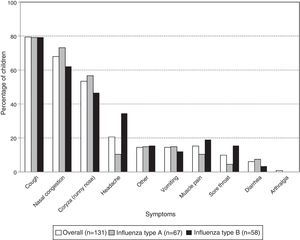

Coughing was the most frequent symptom in children with laboratory-confirmed influenza (79.4% [104/131]) followed by nasal congestion (67.9% [89/131]) and rhinorrhea (53.4% [70/131]). For each of these symptoms, there was no significant difference in frequency between the virus types (Fig. 1). However, there were significantly fewer cases of headache in the children with influenza type A than type B (10.4% [7/67] and 34.5% [20/58]; p-value: 0.0019).

Among the 131 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza, 107 (81.7%) required medical re-evaluation at the emergency department following discharge and two (1.5%) required hospitalization (Table 2). The subsequent follow-up visits were made by most patients, regardless of influenza status; 81.7% of influenza-positive subjects and 87.0% of influenza-negative subjects (p=0.1477). Among influenza cases, a comparable proportion with influenza A (86.6%) and influenza B (74.1%) had subsequent follow-up visits (p=0.1104). At the time of last contact, almost all the children (93.1% [122/131]) had recovered; and 6.9% (9/131) were still recovering.

Subsequent hospitalizations and emergency department visits among cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza (N=131).

| Characteristics | Parameters or categories | Laboratory-confirmed influenza Na=131 | Influenza type A n′b=67 | Influenza type B n′=58 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valuec or nd | %e | Value or n | % | Value or n | % | ||

| Subsequent ER visit | Yes | 107 | 81.7 | 58 | 86.6 | 43 | 74.1 |

| No | 24 | 18.3 | 9 | 13.4 | 15 | 25.9 | |

| Number of Subsequent ER visit | 1 | 48 | 44.9 | 17 | 29.3 | 27 | 62.8 |

| 2 | 38 | 35.5 | 24 | 41.4 | 13 | 30.2 | |

| 3 | 13 | 12.1 | 9 | 15.5 | 3 | 7.0 | |

| 4 | 4 | 3.7 | 4 | 6.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 2 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Number of Subsequent ER visit [numerical] | n | 107 | – | 58 | – | 43 | – |

| Median | 2.0 | – | 2.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Range | 1–8 | – | 1–8 | – | 1–3 | – | |

| Subsequent hospitalization | Yes | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.7 |

| No | 129 | 98.5 | 66 | 98.5 | 57 | 98.3 | |

| Days of subsequent hospitalization | 2 | 2 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| Days of Subsequent hospitalization [numerical] | n | 2 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Median | 2.0 | – | 2.0 | – | 2.0 | – | |

| Range | 2–2 | – | 2–2 | – | 2–2 | – | |

Note: Children with rapid test positive for type A and B are not considered.

ER, emergency room.

The overall median of total direct medical costs associated with each case of laboratory-confirmed influenza was €177.00 (range: €19.00–€4288.00). No significant differences were observed between the medical costs associated with influenza type A (€179.56 [range: €19.00–€4087.68]) and type B (€164.92 [range: €145.83 and €4288.00]) (Table 3). The range in costs relates to the range in treatment received; the majority of patients had an emergency department visit (median €142.71) and all patients received prescription or non-prescription medication (median €8.53). Around 60% of patients had diagnostic costs (median €28.00), around 10% of patients incurred expensive ward costs (median €1646.73) and 1 patient expensive ICU costs (median €1535.19).

Median direct medical costs (in Euros) associated with laboratory-confirmed influenza (N=131).

| Characteristics | Parameters | Laboratory-confirmed influenza Na=131 | Influenza type A n′b=67 | Influenza type B n′=58 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valuec | Value | Value | ||

| Laboratory | nd | 51 | 29 | 20 |

| Median (€) | 37.20 | 41.38 | 28.20 | |

| Range | 6.00–214.02 | 14.20–214.02 | 6.00–143.30 | |

| Radiology | n | 44 | 22 | 19 |

| Median (€) | 13.99 | 13.99 | 13.99 | |

| Range | 13.99–57.72 | 13.99–57.72 | 13.99–13.99 | |

| Other diagnostics | n | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Median (€) | 72.01 | 144.02 | 57.72 | |

| Range | 13.99–201.74 | 86.30–201.74 | 57.72–57.72 | |

| Total for diagnostics | n | 76 | 41 | 31 |

| Median (€) | 28.00 | 28.00 | 27.58 | |

| Range | 6.00–374.38 | 13.99–374.38 | 6.00–181.31 | |

| Prescribed medication [given in the hospital] | n | 87 | 55 | 27 |

| Median (€) | 3.12 | 3.12 | 3.12 | |

| Range | 1.94–90.30 | 1.94–90.30 | 1.94–19.52 | |

| Prescribed medication | n | 129 | 66 | 58 |

| Median (€) | 5.06 | 9.64 | 5.06 | |

| Range | 1.94–119.99 | 1.94–119.99 | 1.94–29.57 | |

| Non-prescribed medication | n | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| Median (€) | 4.62 | 8.69 | 4.58 | |

| Range | 2.47–42.42 | 2.47–42.42 | 3.12–4.62 | |

| Total for treatments | n | 131 | 67 | 58 |

| Median (€) | 8.53 | 12.76 | 8.18 | |

| Range | 3.12–131.21 | 3.14–131.21 | 3.12–32.69 | |

| Ward specific room charge* | n | 14 | 7 | 4 |

| Median (€) | 1646.73 | 1646.73 | 2470.10 | |

| Range | 142.71–3842.37 | 1097.84–3293.46 | 1097.82–3842.37 | |

| ICU* | n | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Median (€) | 1535.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Range | 1535.19–1535.19 | – | – | |

| Total for inpatient charge | n | 14 | 7 | 4 |

| Median (€) | 1646.73 | 1646.73 | 2470.10 | |

| Range | 142.71–3842.37 | 1097.84–3293.46 | 1097.82–3842.37 | |

| ER visit | n | 129 | 66 | 57 |

| Median (€) | 142.71 | 142.71 | 142.71 | |

| Range | 142.70–428.13 | 142.70–428.13 | 142.70–285.42 | |

| Others | n | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Median (€) | 94.69 | 142.40 | 94.69 | |

| Range | 94.69–189.38 | 94.69–189.38 | 94.69–189.38 | |

| Overall total | n | 131 | 67 | 58 |

| Median (€) | 177.00 | 179.56 | 164.92 | |

| Range | 19.00–4288.00 | 19.00–4087.68 | 145.83–4288.00 | |

Note: Children with rapid test positive for type A and B are not considered.

ICU, intensive care unit; ER, emergency room.

Most of the children with laboratory-confirmed influenza (71.8% [94/131]) missed school or day care. The mean absence was 6.6 days (range: 1–15). School absence was recorded in 62.7% (42/67) and 81.0% (47/58) of children with influenza types A and B, respectively. The proportion of domestic contacts with influenza-like symptoms, ARI and/or fever during the study period was significantly higher among children with laboratory-confirmed influenza (25.8% [95% CI: 21.2–31.1]) than among the other children (17.5% [95% CI: 15.0–20.2]) (p=0.0032). The proportion of family contacts developing influenza-like illness was greater in the children with type A than type B influenza (31.7% [95% CI: 25.0–39.3] versus 20.0% [95% CI: 14.3–27.1]).

Among the other causative respiratory viruses, which were isolated in 28.9% (145/501) cases, RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) was the most frequently isolated in 52 (10.4%) isolates [RSV A: 37; RSV B: 12; A+B: 3], followed by rhinoviruses in 40 (8.0%) isolates and adenovirus in 30 (6.0%) isolates. The median ages of the children infected with these viruses were 6.0 months (RSV; range: 0–178 months), 15.5 months (rhinovirus, range: 0–164 months) and 25.0 months (adenovirus, range: 2–146 months). Nine subjects with laboratory-confirmed influenza (6.9% [9/131]) were co-infected with other viruses. Four pathogens (adenovirus, bocavirus, coronavirus and RSV A) were isolated with influenza type A, and three (one coronavirus and two RSV B) were isolated with influenza type B. The most prevalent clinical manifestations in children infected with these pathogens were cough, nasal congestion and rhinorrhea. The highest rate of complications was seen in the subjects with RSV infection (71.2% [37/52]), in whom bronchiolitis was the most important (64.9% [24/37]). The rate of hospital admissions was also higher in these patients (54.0% [20/37]).

DiscussionEvery year, the greatest incidence of influenza occurs in children. Indeed, global incidence rates of up to 49.4 cases per 1000 children under 15 years of age have been published.16 In this University hospital setting, 26.1% of children under 15 years of age with symptoms compatible with influenza-like infections were found to have laboratory-confirmed influenza. This is comparable to Matias et al. (2011), who reported that 32.3% of children presenting with ARI or isolated fever in Spain were positive for influenza.13

In the pediatric population, influenza is responsible for a considerable number of visits to emergency departments, hospitalizations and absences from school; and represents a considerable economic burden each year. Indeed, in our hospital-based study, overall median direct medical costs associated with influenza were €177/case. An appropriate vaccination might reduce this burden.

As observed previously in Spain,13 type B-positive children in our study were older than type A-positive subjects (median age: 66.5 months versus 25.0 months, respectively). These results are similar to those from a study conducted in Finland between 1980 and 1999, where the corresponding mean ages were 4.2 years (type B) and 2.0 years (type A; p<0.001).17

Between 2001 and 2011, the proportion of type B among all influenza viruses in Europe varied from 1.0 to 59.8% during each influenza season.10 However, according to the most recent report from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the type B influenza virus dominated in Spain in 2013, affecting 18.6% of the whole Spanish population; an incidence rate of 14.5 per 100,000.18 In this study, the proportion of children with type B influenza among subjects with laboratory-confirmed disease was 46.0%. This result is similar to that observed by Matias et al. in a study with a similar design, where the influenza type B virus was detected in 47.7% of positive influenza cases in Spain (N=477).13 The presence of the two lineages varies among the influenza cases each season and depends on the geographic location.

Vaccination is an effective way to prevent infection with influenza and its consequences, such as complications and economic burden. In 2010–2011, the influenza strains recommended by WHO for inclusion in the seasonal trivalent vaccine for the northern hemisphere were two influenza type A (strain analogous to A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-like virus; and strain analogous to A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2)-like virus); plus a Victoria lineage of influenza type B (strain analogous to B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus).19 In our study, the majority of laboratory-confirmed cases of type B influenza corresponded to the Victoria strain. Therefore, the type B lineage recommended in the vaccine corresponded to the type B in circulation during the 2010–2011 influenza season. However, either lineage of type B influenza (Victoria or Yamagata) can predominate in any season7,11 and, although the proportion of strains with Yamagata lineage (3.4%) was very low in our study, extensive seasonal variability has been observed. For example, in 2006–2007, 5.5% of B strains were Yamagata lineage compared with 40% in 2007–2008.20 Notably, WHO recommended the use of tetravalent vaccines (i.e., containing both lineages of type B and type A influenza) for the 2012–2013 season in the northern hemisphere.21

Some limitations of the study may affect the interpretation of its results. Firstly, the children were all recruited from a hospital emergency department, where cases are more likely to be more serious and subjected to supplementary tests, compared with cases seen in primary care settings. Conversely, the availability of the rapid diagnostic test results means that the proportion of children presenting with an isolated fever who are subsequently hospitalized is lower than when this test is not available. It is possible that the symptoms recorded during the follow-up telephone interviews may have been under-reported. Finally, the study took place during a single influenza season, therefore the findings may be an over- or under-estimation of influenza burden in other seasons. In addition, since the proportion of influenza types A and B and their lineages may vary, it would be of interest to explore the situation over multiple seasons.

In summary, influenza is responsible for a considerable burden of disease and associated costs in the pediatric population each year. Influenza cases caused by A strains and B strains appear to result in a similar burden in terms of hospitalization and emergency department costs. These could be partially alleviated by appropriate vaccination. The proportion of influenza type A and B during the 2010–2011 season was similar and both lineages of influenza type B (Victoria and Yamagata) were detected among cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza in our study, although the percentage of the Yamagata lineage was low. In the influenza season during this study, there was a good match between influenza strains in the vaccine and circulating strains as the vaccine protected against A strains and the Victoria B lineage. In seasons with a mismatch, however, the vaccine is likely to provide less protection. Given the burden of influenza shown in this study, giving children under 15 years of age vaccines containing lineages of both influenza type A and type B might help reduce the overall burden of illness. Due to the difficulty in predicting which virus strains will be responsible for future influenza seasons, the use of tetravalent vaccines, with their protection against both B lineage strains in addition to A strains, may provide the broadest protection.

FundingGlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA sponsored and funded the study conduct (NCT01592799), analyses of the data and the development and publication of the manuscript.

AuthorshipAll authors of this research paper have directly participated in the design or implementation or analysis, and interpretation of the study and all authors have reviewed and approved the final submitted version. All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the analysis. All authors contributed equally in the manuscript development.

Conflicts of interestGarcía-Martínez JA, McCoig C, García-Corbeira P, Devadiga R and Tafalla M are employees of the GSK group of companies. McCoig C, García-Corbeira P and Tafalla M hold shares in the GSK group of companies as part of their employee remuneration. Arístegui J received investigator fees and honoraria from the GSK group of companies to support the study, for advisory board membership for pediatric vaccines and travel/accommodation/meeting expenses as a speaker at scientific events. Garrote E and Rementeria J report payments received by their respective institutions for study conduct from the GSK group of companies. Ortiz-Lana N reports no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study, all investigators, the study nurses, and other staff members for contributing in many ways to this study. The authors acknowledge Harshith Bhat (GSK) for manuscript writing, Jérémie Dedessus le Moutier (Business & Decision Life Sciences on behalf of GSK) for manuscript coordination and in providing technical inputs during the preparation of this manuscript, Roeland Van Kerckhoven (Keyrus Biopharma on behalf of GSK) and Grégory Leroux (Business & Decision Life Sciences on behalf of GSK) for manuscript coordination, Preethi Govindarajan (GSK) for formatting support and Julia Donnelly (freelance Publication Manager on behalf of GSK) for language editing.

Please cite this article as: Ortiz-Lana N, Garrote E, Arístegui J, Rementeria J, García-Martínez J-A, McCoig C, et al. Estudio prospectivo para estimar la carga de hospitalización y visitas a urgencias de la gripe en población pediátrica en Bilbao (2010–2011). An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:311–319.

Prior presentation at meetings: Presented as a poster at the 7th National Congress of the Spanish Association of Vaccinology, November 25–27, 2013, Cáceres, Spain.