A proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y, a questionnaire to evaluate the Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in children and adolescents, has recently been developed. There are currently no data on the validity and reliability of this tool. The objective of this study was to analyse the validity and reliability of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy version.

MethodologyA core set of self-report tools, including the Spanish version of the EQ-5D-Y were administered to a group of Spanish children and adolescents drawn from the general population. A similar core set of internationally standardised proxy tools, including the EQ-5D-Y Proxy version was administered to their parents. Test–retest reliability was determined, and correlations with other generic measurements of HRQoL were calculated. Additionally, known group validity was examined by comparing groups with a priori expected differences in HRQoL. The agreement between the self-report and proxy version responses was also calculated.

ResultsA total of 477 children and adolescents and their parents participated in the study. One week later, 158 participants completed the EQ-5D-Y/EQ-5D-Y Proxy to facilitate reliability analysis. Agreement between the test–retest scores was higher than 88% for EQ-5D-Y self-report, and proxy version. Correlations with other health measurements showed similar convergent validity to that observed in the international EQ-5D-Y. Agreement between the self-report and proxy versions ranged from 72.9% to 97.1%.

ConclusionsThe results provide preliminary evidence of the reliability and validity of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy version.

Recientemente se ha desarrollado la versión proxy del EQ-5D-Y, un cuestionario para evaluar la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) de niños y adolescentes pero hasta la fecha no existen datos de validez y fiabilidad de este instrumento. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la validez y fiabilidad de la versión proxy del EQ-5D-Y.

MetodologíaSe administró a un grupo de niños y adolescentes españoles de población general una batería de instrumentos autoadministrados que incluía la versión española del EQ-5D-Y. Una batería similar de instrumentos, que incluía la versión proxy en español del EQ-5D-Y, fue administrada a sus padres. Se analizaron la fiabilidad mediante test-retest y la validez mediante correlaciones con otros instrumentos de evaluación de la CVRS. Adicionalmente, se examinó la validez mediante el «análisis de grupos conocidos». Además, se evaluó la concordancia entre las versiones autoadministrada y proxy.

ResultadosUn total de 477 niños y adolescentes participaron en el estudio junto con sus padres. Una semana después, se obtuvieron los datos para realizar el análisis de fiabilidad con 158 participantes, obteniendo una concordancia mayor del 88% en ambas versiones. Las correlaciones con otras medidas de salud indicaron una validez convergente similar a la obtenida en la validación internacional del EQ-5D-Y. Se encontró una concordancia entre las versiones autoadministrada y proxy del 72,9-97,1%.

ConclusionesLos resultados obtenidos evidencian la fiabilidad y validez de la versión proxy del EQ-5D-Y.

In the past decade, there has been a growing interest in researching the health-related quality of life of children and adolescents (HRQoL) in the field of public health.1 Clinicians, researchers, and policy makers are increasingly recognising the importance of measuring HRQoL, as its accurate assessment complements the results of clinical and physiological outcomes and helps integrate the traditional “biomedical model” of health with the “social science or quality of life” model.2 The assessment of HRQoL can help improve health-related decision-making, and some HRQoL instruments can be used in cost-utility analyses of treatments.3 Furthermore, the pharmaceutical industry and the Food and Drug Administration in the United States recognise that HRQoL must be assessed in order to determine the effects of pharmacological treatment on health status.4

There are different generic measures of HRQoL in children and adolescents aged 8 years or more that use self-report questionnaires, such as KIDSCREEN,5 PedsQLTM,6,7 and EQ-5D-Y,8 for which there are validated versions in Spanish.9–11 Still, assessment of HRQoL in individuals with physical or psychological impairments and in children too young to read or write requires the use of proxy instruments to get the necessary information from parents, guardians, physicians, caregivers, etc. These instruments can also be used to assess HRQoL in individuals with low socioeconomic status that have reading comprehension difficulties.11,12

Proxy versions of some of the generic instruments most commonly used in children and adolescents, such as KIDSCREEN and PedsQL™,13 already exist. It has been demonstrated that the information provided by parents in these versions is valid and reliable.13,14 However, the information provided by children, especially in longitudinal studies, may be less consistent due to the changes in attitudes, skills, and priorities characteristic of child development.15

The EQ-5D-Y has the same characteristics and advantages as the EQ-5D version for adults and elderly individuals. It is brief, easy to administer, and provides scores for different health dimensions, as well as an index value that can be used to assess health status. It can also be used in health economic analyses,16 a utility that is not afforded by any of the other HRQoL instruments used in children and adolescents today.

The proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y has been recently translated and adapted for the Spanish population,17 but it has yet to be validated. The purpose of this study was to validate the Spanish version of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy in children and adolescents from the general population.

MethodologySampleThe participants in the study were children and adolescents aged 6–17 years from the general population and their parents. Although the EQ-5D-Y has been validated in children aged 8 years and up, we recruited 6- and 7-year-old participants to include a population with reading difficulties in which the use of proxy instruments becomes necessary.

To ensure a large sample size, we recruited participants through primary and secondary schools in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura from February to May 2012. We requested the participation of a total of 8 schools (4 primary and 4 secondary schools) and 6 of them accepted (2 secondary schools and 4 primary schools). Each centre provided access to 2–4 classes of different grades.

Prior to data collection, the parents were informed of the methodology and objectives of the study by means of an official letter written by the researchers that included an informed consent form. To be included in the study, students had to provide the informed consent form signed by a parent or guardian, attend school on the day the test was administered, and have a good enough level of Spanish to respond in full to the set of questionnaires. The final sample included 477 children and adolescents along with their mothers and/or fathers.

ProcedureThe schedule for data collection was agreed upon with the school principals. The data were collected by a member of the research group using 1 of 2 methods of delivery depending on the age of the participants: face-to-face interviews with participants aged less than 8 years to facilitate a better understanding of the items, and direct administration for children aged 8 years and up. The duration of the survey varied depending on the age of the respondents, from 1h in children 6–8 years old, to half hour in students 16 and 17 years of age.

To collect data from parents or guardians, the students were given a sealed envelope with the set of questionnaires and instructions on how to complete them. A few days later, the filled-out questionnaires were collected from the school. We requested that both parents participate, and specified that we needed at least one parent to respond.

For the purposes of confidentiality and to facilitate data analysis, each respondent was assigned a code.

A phone number and email address were provided to respondents to address any concerns that may arise at any time.

InstrumentsTo examine the convergent validity of the Spanish version of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy, a core set of internationally standardised instruments and variables was administered along with it. We used the same set of instruments as the multinational EQ-5D-Y validity study16 to facilitate future cross-cultural comparisons.

The items included questions on basic socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, level of education, migration status), measures of HRQoL and subjective health, indicators of psychological and physical health problems, and the following assessment tools:

- -

EQ-5D-Y: the self-administered Spanish version of the EQ-5D-Y9 and the recently developed proxy version,17 descriptive systems that comprise 5 items referring to mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression. The respondent can report 3 levels of problems for each item in the dimensions (no problems, some problems, a lot of problems). The EQ-5D-Y and the proxy version also include a visual analogue scale (VAS), where the respondent has to rate his or her own health status (or that of his or her child) on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the worst and 100 the best health state he or she can imagine.

- -

KIDSCREEN-27: the KIDSCREEN-2718 and its proxy version14 were administered as a validated generic instrument to assess HRQoL in children and adolescents. Their 5 dimensions provide detailed profile information on physical wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, autonomy and relationship with parents, relationship with peers and social support, and school environment within the last week. In addition, the KIDSCREEN-10 index score provides a global measure of HRQoL using 10 of the KIDSCREEN-27 items.19

- -

Self-rated health: it was assessed by means of a general health item asking the respondent how he or she would describe his or her health (or that of his or her child) in general. The response options were “excellent”, “very good”, “good”, “fair”, and “poor”. This question has been used in large international health surveys in children and adolescents, and its validity has been demonstrated.20

- -

Cantril's Life Satisfaction Ladder21: this ladder has been used in WHO surveys in children and adolescents. It evaluates the general subjective life satisfaction by asking respondents to picture the best and worst possible lives. These extremes are represented on a ladder that ranges from 0 (the worst) and 10 (the best). Respondents have to indicate where they feel they are standing between these two extremes.

We assessed the reliability of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy by calculating percentages of agreement and kappa coefficients22 to estimate test–retest concordance. We interpreted the kappa values according to Landis and Koch's guidelines,23 with kappa<0.2 indicating poor agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicating fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement, and kappa>0.81 indicating almost perfect agreement. We calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)24 for the VAS, and an ICC>0.7 was considered acceptable.

We assessed convergent validity by determining the correlations between the self-report and proxy versions of the EQ-5D-Y and previously validated measures of HRQoL using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

We hypothesised that the mobility and the pain/discomfort dimensions of the EQ-5D-Y would show a moderate correlation with the dimensions of physical wellbeing of the KIDSCREEN-27, and a significant association with the rest of the HRQoL measures used. Also, we hypothesised that the anxiety/depression dimension of the EQ-5D-Y would show a moderate to high correlation with the psychological wellbeing dimension of the KIDSCREEN-27, and a moderate to high correlation with the VAS and the global HRQoL index of the KIDSCREEN-10, the general health item of the KIDSCREEN-27, and the Life Satisfaction Ladder. Following the guidelines of Cohen,25 coefficients with values ranging from 0.1 to 0.29 were considered low, from 0.3 to 0.49 moderate, and 0.5 and above were considered high.

For each dimension of the EQ-5D-Y, we used the percentage of agreement and the kappa coefficient to analyse the agreement between the self-report and proxy versions. We calculated the agreement between the reports of mothers and children, fathers and children, and fathers and mothers. The statistical significance level was set at P<.05.

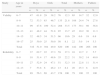

ResultsParticipantsA total of 1328 people responded: 620 children and teenagers aged 6–17 years (326 boys and 304 girls) and 708 parents (442 mothers and 266 fathers) (Table 1). Of the 620 children and adolescents, 477 returned the questionnaires filled out by one or both parents (231 by both parents).

Participants by age and sex (n=620).

| Study | Age in years | Boys | Girls | Total | Mothers | Fathers | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Validity | 6–7 | 47 | 61.8 | 29 | 38.2 | 76 | 12.3 | 65 | 14.7 | 32 | 12.0 |

| 8–9 | 72 | 53.3 | 63 | 46.7 | 135 | 21.8 | 108 | 24.4 | 74 | 27.8 | |

| 10–11 | 99 | 47.6 | 109 | 52.4 | 208 | 33.5 | 173 | 39.1 | 98 | 36.8 | |

| 12–13 | 41 | 48.2 | 44 | 51.8 | 85 | 13.7 | 45 | 10.2 | 30 | 11.3 | |

| 14–15 | 32 | 48.5 | 34 | 51.5 | 66 | 10.6 | 29 | 6.6 | 18 | 6.8 | |

| 16–17 | 25 | 50.0 | 25 | 50.0 | 50 | 8.1 | 22 | 5.0 | 14 | 5.3 | |

| Total | 316 | 51.0 | 304 | 49.0 | 620 | 100 | 442 | 100 | 266 | 100 | |

| Reliability | 6–7 | 37 | 62.7 | 22 | 37.3 | 59 | 37.3 | 10 | 12.7 | 2 | 5.7 |

| 8–9 | 18 | 51.4 | 17 | 48.6 | 35 | 22.2 | 31 | 39.2 | 14 | 40.0 | |

| 10–11 | 27 | 52.9 | 24 | 47.1 | 51 | 32.3 | 18 | 22.8 | 11 | 31.4 | |

| 12–13 | 7 | 53.8 | 6 | 46.2 | 13 | 8.2 | 20 | 25.3 | 8 | 22.9 | |

| Total | 89 | 56.3 | 69 | 43.7 | 158 | 100 | 79 | 100 | 35 | 100 | |

Table 2 shows the prevalence of problems reported by children, mothers, and fathers. We found a low percentage of problems in every dimension, which suggested a high ceiling effect. The dimensions with the highest percentages of problems were the “pain/discomfort” and the “anxiety/depression” dimensions.

Percentage of problems reported in the EQ-5D-Y.

| Children/adolescents (n=620) | Mothers (n=442) | Fathers (n=266) | ||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Mobility | ||||||

| No problems | 96.8 | 600 | 96.8 | 428 | 97.7 | 260 |

| Some problems | 2.6 | 16 | 3.2 | 14 | 2.3 | 6 |

| A lot of problems | 0.6 | 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing values | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-care | ||||||

| No problems | 96.6 | 599 | 95.2 | 421 | 96.2 | 256 |

| Some problems | 3.1 | 19 | 4.8 | 21 | 3.8 | 10 |

| A lot of problems | 0.3 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing values | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Doing usual activities | ||||||

| No problems | 92.7 | 575 | 94.6 | 418 | 95.1 | 253 |

| Some problems | 6.1 | 38 | 5.0 | 22 | 4.9 | 13 |

| A lot of problems | 1.0 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing values | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Having pain or discomfort | ||||||

| No problems | 84.2 | 552 | 81.0 | 358 | 85.7 | 228 |

| Some problems | 15.0 | 93 | 18.8 | 83 | 14.3 | 38 |

| A lot of problems | 0.8 | 5 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing values | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | ||||||

| No problems | 79.8 | 495 | 83.7 | 370 | 86.8 | 231 |

| Some problems | 18.9 | 117 | 15.8 | 70 | 13.2 | 35 |

| A lot of problems | 1.1 | 7 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing values | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

A total of 158 children (6–12 years of age) and 114 parents completed their versions of the EQ-5D-Y twice within the allotted time. The reliability analysis showed a high percentage of agreement between the children, the fathers, and the mothers (Table 3). The pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions showed a slightly lower agreement than the other dimensions, but were above 87%. The kappa coefficient indicated a “substantial” or “nearly perfect” agreement in most dimensions. Only the usual activity dimension showed low agreement in the responses of the mothers based on the kappa coefficient.

Reliability of the EQ-5D-Y and EQ-5D-Y Proxy.

| EQ-5D-Y children/adolescents (n=158) | EQ-5D-Y Proxy, mothers (n=79) | EQ-5D-Y Proxy, fathers (n=35) | ||||

| Kappa coefficient | Agreement (%) | Kappa coefficient | Agreement (%) | Kappa coefficient | Agreement (%) | |

| Mobility | 0.556* | 95.0 | 0.661* | 98.7 | a | 100 |

| Self-care | 0.882* | 97.5 | 0.475* | 94.9 | 1.000* | 100 |

| Doing usual activities | 0.894* | 97.5 | 0.260* | 93.7 | 1.000* | 100 |

| Having pain or discomfort | 0.679* | 89.9 | 0.626* | 87.3 | 0.643* | 88.6 |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | 0.810* | 91.8 | 0.599* | 89.9 | 0.681* | 91.4 |

| VAS | 0.855* | 0.574* | 0.659* | |||

VAS: visual analogue scale.

Table 4 shows that correlations between the dimensions of the EQ-5D-Y and the selected measures of HRQoL were similar for children, mothers, and fathers. Due to the high ceiling effect in the mobility, self-care, and usual activity dimensions, the correlation coefficient between these dimensions and the selected HRQoL measures were low or very low. Correlations were low for the pain/discomfort dimension, and the highest correlation was found with the KIDSCREEN-10 global measure of HRQoL (0.20–0.24). The anxiety/depression measure of the EQ-5D-Y showed a moderate correlation with the “psychological wellbeing” dimension of the KIDSCREEN-27 in children and parents, and with the KIDSCREEN-10 global measure in fathers, mothers, and children. The largest correlation coefficients were found for the VAS, in particular with the KIDSCREEN-10, the subjective general health measure, and the Life Satisfaction Ladder.

Convergent validity: Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between EQ-5D-Y and EQ-5D-Y Proxy, and the KIDSCREEN, subjective general health item, and Life Satisfaction Ladder.

| Children/adolescentsa (n=477) | Mothersa (n=442) | Fathersa (n=266) | |

| Global HRQoL index, KIDSCREEN-10 | |||

| Mobility | −0.090* | −0.107* | −0.056 |

| Self-care | 0.014 | −0.036 | −0.136* |

| Doing usual activities | −0.139** | −0.065 | −0.141* |

| Having pain or discomfort | −0.239** | −0.201** | −0.209** |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | −0.333** | −0.303** | −0.278** |

| VAS | 0.469** | 0.371** | 0.345** |

| Physical wellbeing, KIDSCREEN-27 | |||

| Mobility | −0.043 | −0.099* | −0.065 |

| Self-care | 0.061 | −0.019 | −0.107 |

| Doing usual activities | −0.111** | −0.117* | −0.080 |

| Having pain or discomfort | −0.155** | −0.127** | −0.184** |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | −0.189** | −0.133** | −0.222** |

| VAS | 0.428** | 0.251** | 0.210** |

| Psychological wellbeing, KIDSCREEN-27 | |||

| Mobility | −0.051 | −0.093 | −0.062 |

| Self-care | −0.016 | −0.107* | −0.157* |

| Doing usual activities | −0.129** | −0.091 | −0.117 |

| Having pain or discomfort | −0.195** | −0.122* | −0.179** |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | −0.316** | −0.234** | −0.309** |

| VAS | 0.316** | 0.273** | 0.190** |

| Subjective general health | |||

| Mobility | −0.023 | −0.086 | −0.067 |

| Self-care | 0.017 | 0.040 | −0.017 |

| Doing usual activities | 0.028 | −0.118* | −0.065 |

| Having pain or discomfort | −0.050 | −0.176** | −0.112 |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | −0.060 | −0.175** | −0.090 |

| VAS | 0.336** | 0.211** | 0.237** |

| Life Satisfaction Ladder | |||

| Mobility | −0.048 | −0.093 | 0.011 |

| Self-care | −0.076 | −0.011 | −0.197** |

| Doing usual activities | −0.132** | −0.151** | −0.255** |

| Having pain or discomfort | −0.170** | −0.169** | −0.098 |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | −0.246** | −0.232** | −0.236** |

| VAS | 0.433** | 0.351** | 0.396** |

Statistically significant correlations are shown in bold.

The agreement between self reports and proxy reports is shown in Table 5. We observed a high percentage of agreement in nearly every dimension of the EQ-5D-Y (89.2–97.4%). Agreement between the reports of children and their fathers was very good in the mobility, self-care, and usual activities dimensions, ranging from 88.0% to 97.4%. It was somewhat lower in the pain/discomfort and the anxiety/depression dimensions (72.9–81.2%). These levels were confirmed using kappa coefficients, although the high ceiling effect we found did not allow the calculation of this coefficient in some cases.

Agreement between responses to the self-report and proxy versions of the EQ-5D-Y.

| Children/adolescents-mothers (n=442) | Children/adolescents-fathers (n=266) | Mothers–fathers (n=231) | ||||

| Kappa coefficient | Agreement (%) | Kappa coefficient | Agreement (%) | Kappa coefficient | Agreement (%) | |

| Mobility | a | 95.7 | a | 97.1 | 0.558* | 97.4 |

| Self-care | a | 91.2 | a | 94.7 | 0.653* | 97.4 |

| Doing usual activities | a | 88.0 | a | 91.0 | 0.618* | 96.5 |

| Having pain or discomfort | 0.68* | 72.9 | a | 75.1 | 0.772* | 93.5 |

| Feeling worried, sad, or unhappy | 0.221* | 79.0 | a | 81.2 | 0.564* | 89.2 |

The main finding of this study was that the Spanish version of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy is reliable and valid for use in the general population, showing a high level of agreement with the self-administered version of the EQ-5D-Y. Also, the reliability and validity values we found for the self-administered version of the EQ-5D-Y were consistent with values obtained in previous research.16 In this study, we followed the methodology designed by the experts of the EuroQol group, which was used in the validation study of the international version of the EQ-5D-Y. Thus, it has the advantage of allowing cross-cultural comparison with future studies conducted in other countries.

The feasibility of the proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y in the general population was very high, as there were no missing or inappropriate responses. Only a low prevalence of problems was reported in the different dimensions of the instrument in both the self-completed and the proxy versions. This is typical of HRQoL studies that use samples from the general population, especially in children and adolescents, and is consistent with previous studies.19 A version with 5- rather than 3-level response choices could improve the sensitivity of the EQ-5D-Y to small changes in HRQoL in the general population. This modification has been recently implemented in the EQ-5D-5L, a new version of the original instrument for adults and elderly individuals.26 The greatest percentage of reported problems, both in the self-completed and the proxy versions, was found in the pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions.

The high ceiling effect had a negative impact on some of the reliability and validity analyses. The results showed a very high reliability for the percentage of agreement with the EQ-5D-Y in children, mothers, and fathers (87.3–100%), with the lowest value corresponding to the pain/discomfort dimension (89.9% in children, 87.3% in mothers, and 88.6% in fathers). The kappa coefficient showed good interrater agreement for most dimensions, especially in the responses of fathers. Due to the high ceiling effect, the kappa coefficient could not be used to calculate the mean reliability for the mobility dimension. These results are similar to those obtained in the international EQ-5D-Y validation study conducted in Italy and Spain.16

Regarding convergent validity, we observed similar patterns of associations between the responses of mothers and fathers in the proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y and the version completed by children and adolescents, which were consistent with patterns observed with other instruments validated to measure HRQoL in children and adolescents. As happened in the validation study for the self-completed version, the VAS (a global measure of health) showed a higher correlation with the Life Satisfaction Ladder, the KIDSCREEN-10 index, and the self-rated general health item.16

The correlations between the proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y and other, previously validated HRQoL measures were low or moderate for every dimension, and similar to those observed in past studies.16 Consistent with the study of Ravens-Sieberer et al., the high ceiling effect caused problems in the analyses of correlation, especially for the mobility and usual activity dimensions. Still, our study showed some of the expected associations, such as those between the pain/discomfort dimension and the physical wellbeing dimension of the KIDSCREEN-27 and the KIDSCREEN-10 index, and the association between the usual activities dimension and the Life Satisfaction Ladder.

All participants were healthy children and adolescents that attended school regularly and did not have any serious health problems. To reduce the high ceiling effect and assess the discriminant validity of this instrument, additional research on the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-Y Proxy must be done with the fathers and mothers of children and adolescents with health problems.

The agreement between the self-report and the proxy versions of the EQ-5D-Y was high for every dimension, and especially for mobility, self-care, and usual activities. The lowest agreement was found in the anxiety/depression and pain/discomfort dimensions, but this was expected as these dimensions have a greater psychological component. The agreement between the responses of mothers and fathers was higher than the agreement between the responses of children and their fathers or of children and their mothers in all dimensions, showing a high reliability for respondents to the proxy version.

This study has some limitations. All the participants were children/adolescents and fathers/mothers from the general population, so additional research needs to be done to explore the behaviour of the proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y in specific populations. Other important characteristics of the instrument, such as responsiveness to change, also need to be addressed in future studies. The high ceiling effect we observed indicates that this instrument has low sensitivity in the general population. Consequently, we recommend that it is used in combination with other, more sensitive instruments in the healthy population. Further research is needed to determine the psychometric properties of this instrument in the clinical population and explore its use in health economics assessments. The proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y could be especially useful in the assessment of children younger than 8 years who have difficulty reading or of children and adolescents that have difficulty responding to the questions in the self-completed version.

ConclusionsThis is the first study that assesses the validity and reliability of the proxy version of the EQ-5D-Y. Its results show that this is an applicable, reliable, and valid instrument to measure HRQoL in children and adolescents through parental reports. However, further research is required to analyse its psychometric properties in clinical populations, its responsiveness to change, and its use in health economy analyses.

FundingThis study was funded by the EuroQol Foundation (a non-profit organisation), the Universidad de Extremadura, the Junta de Extremadura and FEDER European regional development funds (GR10127).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gusi N, Perez-Sousa MA, Gozalo-Delgado M, Olivares PR. Validez y fiabilidad de la versión proxy del EQ-5D-Y en español. An Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:212–219.