Acute bronchiolitis (AB) is a very common disease, with a high rate of seasonal hospitalization. Its management requires homogeneous clinical interpretations for which there are different approaches depending on the scales, none of which are properly validated today.

ObjectiveTo create an AB severity scale (ABSS) and to validate it.

Materials and methodsThe development of a parameterized construct with a gradual cumulative score of respiratory rate, heart rate, respiratory effort, auscultation of wheezing and crackles, and the inspiration/expiration ratio. Also, the validation of the ABSS performed on patients diagnosed with AB, and the reliability measured by observing the behaviour of internal consistency, test-retest, external validity and inter-observer agreement.

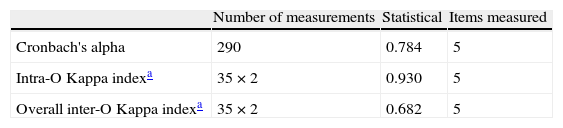

ResultsFrom a total of 290 measurements a Cronbach's reliability alpha of 0.83 was obtained; Kappa agreement index of 0.93 in the test-retest agreement, and Kappa index of 0.682 (α<0.05) for inter-observer agreement.

ConclusionsThe ABSS can be a reliable tool for measuring the severity of AB.

La bronquiolitis aguda (BA) es una enfermedad muy prevalente, con una elevada tasa de hospitalización estacional. Su manejo requiere de interpretaciones clínicas homogéneas, para lo cual existen diversas aproximaciones a través de escalas, ninguna de la cuales están validadas en la actualidad.

ObjetivoCreación de una Escala de Severidad de la BA (ESBA) y su validación.

Material y métodoElaboración de un constructo con parámetros graduales de puntuación acumulativa de la frecuencia respiratoria, frecuencia cardiaca, esfuerzo respiratorio, auscultación de sibilancias y crepitantes y relación inspiración/espiración. Validación de la ESBA sobre pacientes diagnosticados de BA; la fiabilidad medida a través de la observación del comportamiento de su consistencia interna, test-retest, validez externa y concordancia interobservadores.

ResultadosSobre un total de 290 mediciones, se obtuvo una fiabilidad para un alfa de Cronbach del 0,784, índice de acuerdo Kappa del 0,93 en el test-retest y un índice de acuerdo Kappa del 0.682 (α<0,05) para la concordancia entre observadores.

ConclusionesLa ESBA puede ser un instrumento de fiable para medir la gravedad de la BA.

Clinical assessment of the condition of patients with acute bronchiolitis (AB) is of enormous interest to paediatricians as an essential step before making decisions on an infant suffering from this common disease. Recent clinical practice guidelines encourage the creation and validation of scales for measuring the severity of AB.1 There are several published rating scales,2–9 the most widely used being the Wood-Downes-Ferrés (WDF) scale.2,7 Given that this scale has not been validated and that it was not originally designed for patients with AB, its widespread use does not seem justified. Its initial approach to clinical assessment of asthma is not well suited to a disease with the pathophysiology of AB. There are various issues discussed below that call into question its applicability for infants with bronchiolitis. We propose to present and validate a scale for measuring the severity of AB that can help with initial evaluation and follow-up of this disease, on the basis of a critical and constructive examination of existing scales, whether for the assessment of respiratory disease or for bronchiolitis.3–8

Materials and methodsOn the basis of the theoretical premises of previous studies related to the cardiorespiratory physiology of infants,5–7,9 and a critical and constructive examination of existing scales, whether for the assessment of respiratory disease or for bronchiolitis,3–8 we have designed a clinical assessment scale whose construct is shown in Table 1. This scale was discussed and remodelled before and during application by the members of staff responsible for care of patients with bronchiolitis. The resulting construct scale consists of 5 cumulative discontinuous scoring items, with a maximum of 13 and a minimum of 0 points. The items included are related to the pathophysiological findings for AB, which reinforces their content validity for subsequent construct validity. They are wheezing, crackles, effort, inspiration/expiration ratio, heart rate and respiratory rate.

Construct of the acute bronchiolitis severity scale.

| Age | Sex | GA |

| Wheezing/crackles-effort-I:E ratio | ||

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Wheezing | No | Wheezing at end of expiration | Wheezing throughout expiration | Ins-expiratory wheezing | Hypoventilation |

| Crackles | No | Crackles in one field | Crackles in 2 fields | Crackles in 3 fields | Crackles in 4 fields |

| Effort | No effort | Subcostal or lower intracostal retractions | +suprasternal retractions or nasal flaring | +nasal flaring and suprasternal (universal) | |

| I:E ratio | Normal | Symmetrical | Inverted |

| Respiratory rate | 0 Point | 1 Point | 2 Points |

| Age (months) | |||

| <2m | <57 | 57–66 | >66 |

| 2–6m | <53 | 53–62 | >62 |

| 6–12m | <47 | 47–55 | >55 |

| Heart rate | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points |

| Age | |||

| 7 days–2 months | 125–152 | 153–180 | >180 |

| 2–12 months | 120–140 | 140–160 | >160 |

I:E: inspiration/expiration.

The assessment of wheezing was graduated from 0 to 4 points, ranging from none to wheezing at the end of expiration, during the whole expiration, in both inspiration and expiration phases, and finally hypoventilation and decreased airflow without wheezing. Crackles were graduated from 0 to 4, adding a point for each of the anterior and posterior fields of each hemithorax with persistent crackles at every breath on auscultation. Effort was graduated from 0 to 3 points, ranging from no effort to mild subcostal and lower intercostal retractions, the latter plus nasal flaring or suprasternal retractions, and finally retractions in all fields. The inspiration/expiration (I:E) ratio was graduated from 0 to 2: normal, symmetrical or inverted.

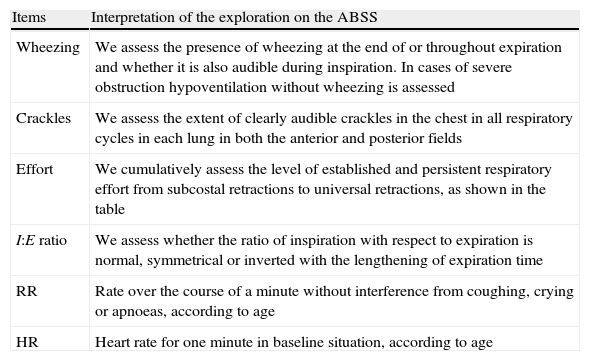

Respiratory rate (RR) and heart rate (HR) were stratified by age, as in previous studies.10–12 The cut-off points for each age were based on standard deviation. Thus more than one standard deviation away from the mean scored 1 point, and more than 2 scored 2 points. The interpretation pattern for each category is summarized in Table 2. It is included on the individual data collection sheet.

Summary of interpretation of the items in the ABSS.

| Items | Interpretation of the exploration on the ABSS |

| Wheezing | We assess the presence of wheezing at the end of or throughout expiration and whether it is also audible during inspiration. In cases of severe obstruction hypoventilation without wheezing is assessed |

| Crackles | We assess the extent of clearly audible crackles in the chest in all respiratory cycles in each lung in both the anterior and posterior fields |

| Effort | We cumulatively assess the level of established and persistent respiratory effort from subcostal retractions to universal retractions, as shown in the table |

| I:E ratio | We assess whether the ratio of inspiration with respect to expiration is normal, symmetrical or inverted with the lengthening of expiration time |

| RR | Rate over the course of a minute without interference from coughing, crying or apnoeas, according to age |

| HR | Heart rate for one minute in baseline situation, according to age |

ABSS: Acute bronchiolitis severity scale.

The inclusion criteria in the study were infants less than one year of age admitted with AB, both from respiratory syncytial virus and other viruses, with no other associated disease. The exclusion criteria were clinical and/or analytical suspicion of bacterial superinfection or pre-existing chronic comorbidity and prematurity of less than 35 weeks’ gestation, a limit related to the inclusion criteria for prevention with palivizumab in our hospital. An optimal measurement was considered to be one carried out with the patient awake, naked, afebrile after aspiration of secretions and more stable than their clinical situation would permit without close administration of adrenergic drugs.

Patients diagnosed with AB that met the inclusion criteria were assessed by physicians using the ABSS independently, without knowing the results of the other assessors, on admission, during hospitalization and on discharge. The medical staff who decided where to place patients with AB were unaware of or disregarded in principle the results of application of the ABSS on admission to the ward or the PICU. Doctors undergoing residency training (6 first-year and 3 second-year residents) as well as senior permanent staff on the ward (3 staff physicians) took part in applying the scale. Retesting of the patients was performed by a single senior doctor during their admission on stable patients and within a short period of time, not more than one hour, to avoid bias arising from a clinical change in the patient's condition. The results were obtained blind before being transmitted to the data collection staff. To achieve inter-observer agreement, measurements were taken by all the staff investigators included in the study in random pairs to try to avoid uniformity bias and make the application more universal. The ABSS was also used to assess all those patients affected by AB that met the clinical criteria for admission to paediatric intensive care. We took several simultaneous measurements for each patient during admission and collected them at the end in an individual form. We followed our hospital's ethics and confidentiality protocols.

The reliability of the ABSS was statistically analyzed by establishing internal consistency using Cronbach's coefficient, following alpha factor analysis. A Cronbach's alpha of over 0.7 was regarded as indicating good internal consistency. Inter-observer agreement was assessed over the final results of the application of the ABSS through the level of agreement obtained by the same sample being assessed in the same conditions by any 2 assessors using the Kappa index. Agreement in each category was also assessed separately. An acceptable index was estimated as a minimum of 0.6, with an alpha error probability of α<0.05. The same requirements were applied to intra-observer assessment.

Since there is no existing scale to serve as a “gold standard”, we drew a correlation with the severity of condition that determined the placement of the patient according to clinical criteria independent of the study: address, ward and PICU. On this basis, and in contrast to the empirical approaches previously established in the literature,1,4,13,14 we fixed cut-off points for severity of AB in a qualitative gradation: mild, moderate, and severe. The information was processed using the SPSS statistical package version 15.0.

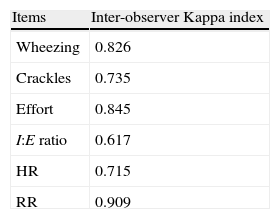

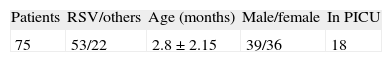

ResultsFrom a total of 75 patients in 3 epidemic seasons who fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in our study, 290 optimal measurements were obtained by means of the ABSS during their hospitalization. The estimated internal reliability using Cronbach's alpha was 0.784. The Kappa agreement index for each item is included in Table 3. Test-retest reliability was performed on 35 assessments and inter-observer reliability on 35 assessments, with a Kappa agreement index of 0.93 and 0.682 respectively (Table 4). The clinical/demographic distribution of the patients included in the study is shown in Table 5.

Inter-observer Kappa agreement indexa of the various ABSS items in the sample.

| Items | Inter-observer Kappa index |

| Wheezing | 0.826 |

| Crackles | 0.735 |

| Effort | 0.845 |

| I:E ratio | 0.617 |

| HR | 0.715 |

| RR | 0.909 |

ABSS: Acute bronchiolitis severity scale; HR: heart rate; I:E: inspiration/expiration; RR: respiratory rate.

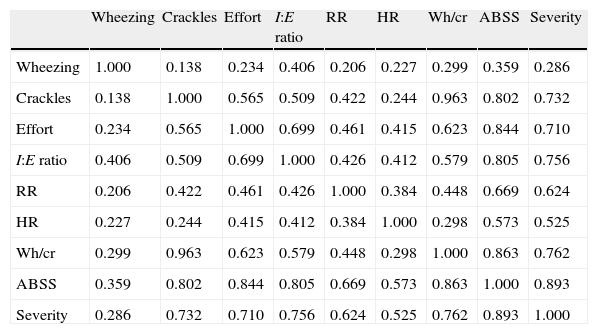

The ABSS assessment for admission was a score (mean±standard deviation) of 7±2.37 points. Discharge from hospital was at an ABSS score of 2±1.2 and admission to the PICU at 11±0.92 respectively. This led us to establish three levels of severity: mild from 0 to 4 points, moderate from 5 to 9 and severe from 10 to 13. A factor analysis of the results was performed for these three levels of severity, with the other study variables. The matrix of correlations between elements is shown in Table 6.

Correlation matrix.

| Wheezing | Crackles | Effort | I:E ratio | RR | HR | Wh/cr | ABSS | Severity | |

| Wheezing | 1.000 | 0.138 | 0.234 | 0.406 | 0.206 | 0.227 | 0.299 | 0.359 | 0.286 |

| Crackles | 0.138 | 1.000 | 0.565 | 0.509 | 0.422 | 0.244 | 0.963 | 0.802 | 0.732 |

| Effort | 0.234 | 0.565 | 1.000 | 0.699 | 0.461 | 0.415 | 0.623 | 0.844 | 0.710 |

| I:E ratio | 0.406 | 0.509 | 0.699 | 1.000 | 0.426 | 0.412 | 0.579 | 0.805 | 0.756 |

| RR | 0.206 | 0.422 | 0.461 | 0.426 | 1.000 | 0.384 | 0.448 | 0.669 | 0.624 |

| HR | 0.227 | 0.244 | 0.415 | 0.412 | 0.384 | 1.000 | 0.298 | 0.573 | 0.525 |

| Wh/cr | 0.299 | 0.963 | 0.623 | 0.579 | 0.448 | 0.298 | 1.000 | 0.863 | 0.762 |

| ABSS | 0.359 | 0.802 | 0.844 | 0.805 | 0.669 | 0.573 | 0.863 | 1.000 | 0.893 |

| Severity | 0.286 | 0.732 | 0.710 | 0.756 | 0.624 | 0.525 | 0.762 | 0.893 | 1.000 |

ABSS: Acute bronchiolitis severity scale; HR: heart rate; I:E: inspiration/expiration; RR: respiratory rate; severity: stratified in 3 levels; wh/cr: wheezing/crackles.

The creation of our construct is underpinned by constructive criticism and discussion of existing scales. We therefore need to begin by saying that the mostly widely used scale, the WDF, does not take account of two extremely important parameters, respiratory rate and heart rate, both of which are closely related to the age of the patient. It does not seem reasonable to use a heart rate of 120bpm as the scoring threshold for all ages, with only 2 alternatives. This negates its discriminatory value in respect of the age of the infant. Stratifying it by age, as in some hospital scales,3 provides a more accurate reflection of the real state of the patient. In this way, the valuable information on linear and relatively objective parameters such as HR and RR is not lost.

Moreover, even allowing for the subjectivity inherent in a clinical assessment, parameters such as “air intake” are difficult to quantify, as they are clear when the breath sounds are normal and when the chest is silent due to a serious obstruction, but the gradations of intermediate possibilities are very difficult to define. On the other hand, “air intake” is the result of other assessment criteria, namely “RR”, “wheezing” and “crackles”. Thus a small degree of obstruction to airflow causes wheezing at the end of expiration, and if the obstruction is larger it may affect the whole of expiration and even inspiration. This obstruction will give rise to air trapping and reduction of tidal volume, which will be compensated by a parallel increase in RR, resulting in increasingly shallow breathing and reduced air intake the more severe it becomes. Similarly, extension of crackles will give us an approximate idea of the severity of the pattern of restriction, and compensating for it will also increase RR. Air intake is therefore a result of the degree of obstruction and restriction, both of which are related to RR. It is reasonable to seek to avoid this parameter so as to achieve greater objectivity and reinforce the more objective assessment of RR, wheezing and crackles, and for this reason “air intake” is not included in our scale. In certain patients the “wheezing” parameter does not provide an appropriate score in cases of severe obstruction where wheezing can no longer be heard because so little airflow is produced. We therefore propose a grading of 0–4 possible auscultatory findings, that is, one more than the WDF scale.

The presence of crackles, inherent to AB,13,15 is an indication of the parenchymal extension of bronchiolitis. We therefore established an assessment for this item in four fields, two anterior and two posterior, with a grading from 0 to 4. Since this item is pathophysiologically dissociated from the degree of obstruction (the greater the obstruction the fewer the crackles, because the alveoli are less distensible), its score is linked to that for wheezing. Moreover, in certain AB patients, wheezing does not occur. In younger patients the smaller size of the airway explains why patterns of hypoventilation and/or crackles predominate in auscultation compared with wheezing. In our subsequent statistical study, Cronbach's alpha gave a higher result when the item with the higher score out of wheezing and crackles was quantified. The factor analysis also showed the lesser correlation of this parameter with the score for the “crackles” variable (Table 6).

Another parameter in the WDF scale, cyanosis, is in general late appearing and almost always serious in itself. It is highly dependent on the lighting level in the examination room. It may also be a confounding factor in the event of anaemia, a very common situation in infancy, since in that case cyanosis may not appear until hypoxaemia is very severe. Moreover it is difficult to stratify the degree of cyanosis and therefore some clinical assessment scales do not include it.3,4,8,9

An interesting and relatively objective parameter is time of inspiration/expiration related to effort and degree of obstruction. Thus as the obstruction progresses and fatigue through laboured breathing increases, inspirations will become increasingly short and expirations increasingly long. Scarfone's pulmonary index gives a graded assessment according to the coefficient of the two respiratory phases.6 The I:E ratio is also assessed in the bronchiolitis clinical guidelines by other authors.4 The evolution of worsening bronchiolitis will go from a physiological situation in which I>E to an intermediate I=E, and finally a reversal of the situation, I<E. The ease of determining this has led us to include in it the scale construct. It is the weakest parameter in terms of the index of agreement of the scale (Table 3), but its Kappa value does at least exceed 0.6 and it maintains good internal consistency with the other parameters and with the overall ABSS score (Table 6). We have therefore kept it in the ABSS. The final factor analysis offers interesting data such as the correlation of severity (see “Severity” column in Table 6) with the different variables, showing a clear predominance of the relationship with overall ABSS score. It is striking that the variable that expresses the lowest association in itself is wheezing.

The inclusion of measurements requiring equipment such as oximetry saturation or capnometry, as in some proposed scales,3,8 diminishes the clinical potential of the supposed universality of a scale that can be extended outside the hospital environment. We therefore believe that a true assessment scale must be based on exploratory parameters, such as the one we have designed and applied. Besides, reduced saturation is a late symptom which correlates poorly with the severity of AB, and it has therefore not been taken into account.

The limitations of our work lie in the fact that it is circumscribed to a hospital setting and to that of a single hospital. Although the sample of patients included in the study is no different from those in similar publications16 in terms of epidemiological variables (Table 5), the infants included in it are smaller and more seriously affected than in a community environment (virtually 80% of the infants were younger than five months). The number of ABSS assessors is limited and this may give rise to a certain biased uniformity in the application of the ABSS. Another limitation is that for inter-observer agreement the time that elapses between two examinations may alter the clinical situation, on the one hand, and on the other the score may be remembered by the assessor. The incidence of the number of patients in PICU, though disproportionate for the sample size, is limited.

Analysis of the data allows us to infer that although the ABSS may be useful in general, the exploratory skill of senior staff may make its use more reliable. In any case, we believe that it would be of interest to carry out application studies outside the hospital environment, as well as in other hospitals, to reinforce the usefulness of the ABSS.

Conclusions and commentsThe level of reliability obtained, the inter- and intra-observer agreement, the content validity, the construct validity and the direct relationship with clinical handling of patients during hospitalisation as external validity allow us to put forward our ABSS as a sufficiently reliable measure of the severity of AB in infants. It consists of an aggregate score for the parameters wheezing/crackles (the greater of the two important), respiratory effort, I:E ratio, HR and RR. It is stratified in three levels of severity: mild from 0 to 4 points, moderate from 5 to 9 and severe from 10 to 13. It is a tool that may offer us a more objective formulation of the concept of severity for decision-making and communication among professionals involved in the care of AB.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ramos Fernández J, Cordón Martínez A, Galindo Zavala R, Urda Cardona A. Validación de una escala clínica de severidad de la bronquiolitis aguda. An Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:3–8.