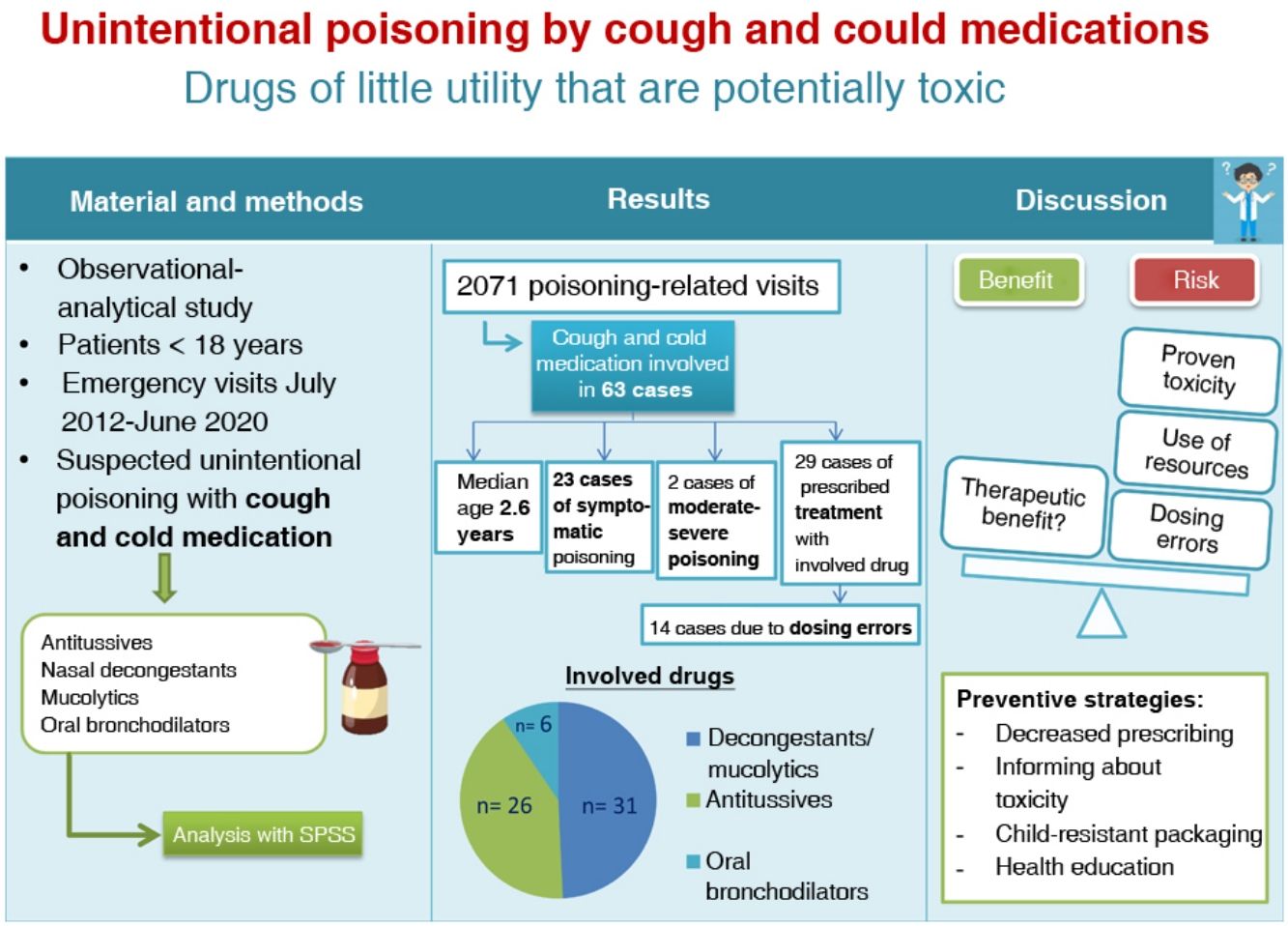

The use of medications to relieve the symptoms of the “common cold” in children is very frequent. In addition to the lack of scientific evidence supporting its usefulness, there is evidence of potential toxicity, and serious and even fatal cases of intoxication have been described. The objective was to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the patients treated in a paediatric emergency department (PED) for suspected unintentional intoxication by a cold medicine.

Material and methodsObservational and analytical study of patients aged less than 18 years managed in a PED for suspected unintentional poisoning by a cold medicine between July 2012 and June 2020. We classified severity according to the Poisoning Severity Score (PSS): PSS-0 = no toxicity; PSS-1 = mild toxicity; PSS-2 = moderate; PSS-3 = severe; PSS-4 = lethal. If the intoxication occurred while the patient was in active treatment with the drug, we determined whether the patient’s age was in the applicable range established in the therapeutic indications provided in the summary of product characteristics.

ResultsThe study included data for 63 cases. The drugs involved were decongestants and mucolytics (31; 49.2%), antitussives (26; 41.2%) and oral bronchodilators (6; 9.5%). The distribution by severity was 40 cases with PSS-0 (63.5%), 21 with PSS-1 (33.3%), 1 with PSS-2 (1.6%) and 1 with PSS-3 (1.6%). In 29 patients (46.0%) there was a history of therapeutic use; in 15 of these cases (51.7%) the age was lower than recommended in the summary of product characteristics. In 14 patients (22.2%) the intoxication was due to administration of the wrong dose by caregivers.

ConclusionAlthough scientific evidence does not support the use of cold medicines in children, unintentional intoxications by these drugs keep happening, in some cases causing moderate or severe symptoms.

El uso de medicamentos para aliviar los síntomas del “resfriado común” en los niños es muy frecuente. A la falta de evidencia científica que avale su utilidad se suma la potencial toxicidad, habiéndose descrito intoxicaciones graves e incluso letales. El objetivo de este estudio es describir las características clínico-epidemiológicas de los pacientes atendidos en un Servicio de Urgencias Pediátricas (SUP) por sospecha de intoxicación no intencionada por anticatarrales.

Material y métodosEstudio analítico-observacional de los pacientes con edad inferior a 18 años atendidos en un SUP por sospecha de intoxicación no intencionada por un medicamento anticatarral, entre julio-2012 y junio-2020. Se clasificó la gravedad según el Poisoning Severity Score (PSS): PSS-0 = sin toxicidad; PSS-1 = toxicidad leve; PSS-2 = moderada; PSS-3 = grave; PSS-4 = letal. Si la intoxicación se produjo en el transcurso de un tratamiento con el medicamento, se determinó si la edad del paciente estaba incluida en las indicaciones terapéuticas según ficha técnica.

ResultadosSe recogieron 63 casos. Los medicamentos implicados fueron: anticongestivos y mucolíticos (31; 49,2%), antitusígenos (26; 41,2%), broncodilatadores orales (6; 9,5%). Se clasificaron según gravedad en: PSS-0 = 40 (63,5%), PSS-1 = 21 (33,3%), PSS-2 = 1 (1,6%) y PSS-3 = 1 (1,6%). En 29 pacientes (46,0%) existía antecedente de uso terapéutico; de éstos, en 15 casos (51,7%) la edad del paciente era inferior a la recomendada en ficha técnica. En 14 pacientes (22,2%) la intoxicación se produjo por error en la dosis administrada por los cuidadores.

ConclusiónAunque la evidencia científica no recomienda medicamentos anticatarrales en niños, se siguen produciendo intoxicaciones no intencionadas por estos fármacos, en ocasiones moderadas o graves.

The use of medicines to alleviate the symptoms of the common cold in children is frequent, and includes cough suppressants, nasal decongestants, expectorants and antihistamines, among others1,2. Formulations combining more than one active principle are commercially available, and in Spain, they can be obtained without a medical prescription. These drugs are frequently used at ages below those recommended in the summary of product characteristics1,2, which can increase the risk of poisoning. The lack of scientific evidence on the usefulness of these drugs3–7 is aggravated by their potential toxicity, as severe and even lethal cases of poisoning have been reported8–21.

Large case series of cold and cough medicine poisoning in children describing moderate, severe and lethal reactions have been published in the literature, in addition to numerous isolated case reports8–14. Also, the annual reports of the National Poison Data System (NPDS) of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) include 9 cases of fatal poisoning in children under 8 years between 2000 and 2019 in which a one-time ingestion of cough or cold preparations was undoubtedly or probably responsible for the fatality15–21.

The aim of our study was to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the patients managed in a paediatric emergency department (PED) for suspected unintentional poisoning by preparations used to treat common colds.

Material and methodsWe conducted an observational descriptive study in the PED of a tertiary care urban women’s and children’s hospital that manages approximately 110 000 paediatric visits per year. We selected patients aged less than 18 years who presented to the emergency department with suspected unintentional poisoning by cold and cough preparations between July 2012 and June 2020. The drugs under consideration included cough suppressants, nasal decongestants, mucolytics and oral bronchodilators. We excluded cases of exposure to an antihistamine as the sole active ingredient.

The drugs we identified as causing severe poisoning in the paediatric age group, on account of reports of cases of life-threatening toxicity in children under 8 years, are narcotic antitussives, antihistamines, sympathomimetic decongestants and imidazoline decongestants22.

To select the cases, we reviewed the health records of all patients whose reason for the visit or final diagnosis was related to toxic substance exposure.

Through the retrospective review of electronic health records, we collected data on epidemiological, clinical and management variables. We assessed the toxicity of the episode based on the ingested dose and the presence of clinical manifestations suggestive of toxicity. A dose was considered toxic based on the dose information available in the TOXBASE database of the National Poison Information System23. We used the poisoning severity score (PSS)24 to grade the severity of poisoning as PSS-0 (absent), PSS-1 (minor), PSS-2 (moderate), PSS-3 (severe) and PSS-4 (fatal). For the comparative study of drug classes, we grouped patients that ingested any opioids and those that ingested any antihistamines.

We reviewed emergency department charts and electronic health records searching for information that the patient was in treatment with the drug involved in the reason for the visit. When poisoning occurred in the context of prescribed treatment, we checked whether the age of the patient was included in the age range established in the summary of product characteristics, which we obtained from the medicine online information centre of the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices)25.

The emergency encounter chart in the electronic health record system of the PED includes a specific template for the anamnesis of patients with suspected poisoning, which facilitates complete documentation. In addition, the electronic system records both the actions performed and the time of their performance.

We collected and processed all the data in a Microsoft Access relational database (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, USA). The statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS version 25.0 for Windows. Quantitative data were summarised as median and interquartile range and categorical data as absolute frequency and percentage distributions. We used tests to analyse the distribution of the data (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) and to compare quantitative data (Student t, Mann-Whitney U) and qualitative data (chi square, contingency tables, Fisher exact test). We considered P-values of less than .05 statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research with Medicines of the hospital where the study was conducted (file PIC-63-19).

ResultsWe selected 63 cases of a total of 2171 encounters for suspected poisoning (2.9%). In this total, 36 occurred in male patients (57.1%), and the median age of the sample was 2.6 years (interquartile range [IQR], 1.8–3.6). In 42 cases (66.6%) in which the setting of the exposure was documented, the exposure took place at home.

The involved drugs were decongestants and mucolytics (31; 49.2%), antitussives (26; 41.2%) and oral bronchodilators (6; 9.5%). In 25 cases (39.6%), the involved commercial preparation was a combination of several active ingredients. Thirty-four patients (53.9%) ingested at least 1 drug previously known to cause severe poisoning in children, which was a narcotic antitussive in 13 cases (20%) and an antihistamine combined with other active ingredients in 21 (33.3%).

In 30 cases (47.6%), the exposure was deemed potentially toxic due to ingestion of a toxic or unknown dose or to the presence of symptoms of intoxication.

Twenty-three patients (36.5%) presented with symptoms suggestive of intoxication. We established the distribution by severity applying the PSS, with the following results: PSS-0, 40 (63.5%); PSS-1, 21 (33.3%); PSS-2, 1 (1.6%); PSS-3, 1 (1.6%).

Twenty-nine patients (46%) underwent gastrointestinal decontamination, all through the administration of activated charcoal, and in 1 case, preceded by gastric lavage. The time of ingestion was known in 26 cases, and the median time elapsed between ingestion and decontamination was 82 min (IQR, 62–116). One patient (1.6%) received an antidote (naloxone).

Two patients (3.2%) required admission to hospital, but neither required admission to the paediatric intensive care unit.

The case of severe poisoning occurred in a boy aged 2 years that presented with central nervous system and respiratory depression following the accidental ingestion of an unknown amount (up to a maximum of 15 mg/kg) of dextromethorphan syrup. The boy required life support measures and infusion of naloxone, and had a favourable outcome.

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the patients based on the involved drug.

Clinical characteristics and management of patients based on the involved cough and could medication.

| Cloperastine (n = 13) | Chlorpheniramine + phenylephrine + diphenhydramine (n = 18) | Codeine (n = 2) | Dextromethorphan, alone or with pseudoephedrine (n = 13) | Mepifiline (n = 2) | Promethazinea (n = 3) | Low-toxicity substancesb (n = 6) | Terbutalinea (n = 6) | Total (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health transport | 0 | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | 3 (23.1%) | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 1(16.7%) | 7 (11.1%) |

| Time from ingestion to visit (hours)c | 1 (0.8−1.5) | 1.5 (1−2.2) | 2.7 (0.5–5) | 3.8 (1−6) | 1 (-) | 2 (1.8−4.5) | 3.5 (1−4) | 10.7 (2–18) | 1.5 (1−4) |

| Dosing error | 2 (15.4%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 | 4 (30.8%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 14 (22.2%) |

| Ingestion of dose above toxic thresholdd | 0 | 8 (44.4%) | 0 | 10 (76.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (83.3%) | 23 (36.5%) |

| Severity of poisoning | |||||||||

| PSS-0 | 13 (100%) | 16 (88.9%) | 2 (100%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0 | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (50%) | 1 (16.7%) | 40 (63.5%) |

| PSS-1 | 0 | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | 8 (61.5%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (50%) | 5 (83.3%) | 21 (33.3%) |

| PSS-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6%) |

| PSS-3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6%) |

| Symptoms | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (3.2%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 3 (50%) | 2 (33.3%) | 10 (15.9%) |

| Neurologic | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 6 (46.1%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 11 (17.5%) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (15.4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.2%) |

| Gastrointestinal decontamination | 10 (76.9%) | 11 (61.1%) | 0 | 5 (38.5%) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 29 (46.0%) |

| Antidote administration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6%) |

| Diagnostic tests | |||||||||

| Blood tests | 1 (7.6%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 7 (11.1%) |

| ECG | 5 (38.5%) | 15 (83.3%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (100%) | 27 (42.9%) |

| Length of PED visit in hours | 3.1 (2.4−3.3) | 3.2 (1.7−5) | 0.7 (0.6−0.8) | 1.9 (0.7−4.3) | 0.7 (-) | 0.9 (0.7−2.4) | 1.2 (0.9−2.2) | 2.6 (2.4−3.1) | 2.5 (0.9−3.7) |

| Hospital admission | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.2%) |

ECG, electrocardiogram; PED, paediatric emergency department; PSS, Poisoning Severity Score (PSS-0 = absent; PSS-1 = minor poisoning; PSS-2 = moderate poisoning; PSS-3 = severe poisoning).

Qualitative data expressed as absolute frequency (percentage). Quantitative data expressed as median (interquartile range).

When we compared patients exposed to opioids (codeine or dextromethorphan; n = 15) to all other patients, we found statistically significant differences in the frequency of ingestion of doses above the toxic threshold (10 [66.7%] vs 13 [27.1%]; P = .005) and of the presence of symptoms (10 [66.7%] vs 12 [25%]; P = .003). We also found a tendency to greater severity of poisoning (2 vs 0 patients with episodes categorised as PSS 2–3; P = .054). When we compared the group of patients that ingested an antihistamine (chlorpheniramine + diphenhydramine, mepifiline or promethazine; n = 23) to the rest, we found statistically significant differences in the frequency of performance of diagnostic tests (16 [69.6%] vs 16 [40.0%]; P = .024), specifically electrocardiography (15 [65.2%] vs 12 [30.0%]; P = .007). Lastly, when we compared the group of patients exposed to terbutaline (n = 6) to the rest, we found differences in the median time elapsed between ingestion and the PED visit (10.75 vs 1.5 h; P = .015), the frequency of an ingested dose above the toxic threshold (5 [83.3%] vs 18 [31.6%]; P = .021) and the performance of electrocardiography (6 [100%] vs 21 [36.8%]; P = .004).

Out of the total sample, the fact that the patient was in treatment with the involved drug was documented in 29 cases (46.0%). In 15 of them (51.7%), the age of the patient was under the age limit recommended in the summary of product characteristics.

In the subset of 29 patients in treatment, the overdose occurred due to administration of an erroneous dose by the caregiver in 14 cases (48.3%) and to unsupervised ingestion in 15 (51.7%). In all cases in which the patient was not in treatment (n = 34), the mechanism of poisoning was unsupervised ingestion.

When we compared patients in which the overdose mechanism was a medication error (n = 14) to those in which it was unsupervised ingestion (n = 49), we found statistically significant differences in the median time elapsed from ingestion to care seeking (4.5 vs 1.5 h; P = .023) and in the administration of any treatment in the PED (4 [28.6%] vs 29 [59.2%]; P = .043).

DiscussionTreatments for the common cold frequently include drugs that are highly toxic in children22 that can, on occasion, cause moderate to severe poisoning.

The epidemiological characteristics of the patients in our sample were similar to those described by the Working Group on Poisoning of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría (SEUP, Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine)26–28. The most recent data, corresponding to the cases recorded in the Toxicology Observatory of the SEUP between 2008 and 2017, show that most unintentional drug ingestions occur in early childhood (86.1% in children <6 years), in the home (85.5%) and with a slightly greater frequency in boys (53.5%)28. As regards clinical manifestations, the proportion of patients that developed symptoms was greater in patients that ingested cold and cough medication (36.5%, based on the presented data) compared to the overall group of medication ingestions (25.7%)28.

Our study found that most cases of exposure to cold and cough medication involved drugs that are highly toxic in the paediatric age group, specifically opioids and antihistamines combined with other active ingredients. Although all cases had good outcomes, numerous publications have evinced the potential severity of these poisonings.

An extensive review of cases conducted by Dart et al. identified 99 fatalities following ingestion of cough and cold medications in children aged less than 6 years, and pseudoephedrine, diphenhydramine and dextromethorphan were the most frequently involved active ingredients8.

The annual reports of the National Poison Data System of the AAPCC published since 2000 have included 5 fatal cases in children aged less than 6 years following ingestion of cough and cold medication containing an antihistamine (chlorpheniramine in 3 cases). In every case, the child was found in cardiac arrest16–18,20.

In our sample, the most frequently involved preparation was the combination of chlorpheniramine-phenylephrine-diphenhydramine, although toxicity was only evinced in 2 cases and was minor. The low severity in these patients can be partially explained by the fact that the ingested dose exceeded the toxic threshold in less than half of the cases. Furthermore, the time elapsed between ingestion and the PED visit was relatively short (median, 1.5 h) and gastrointestinal decontamination was performed in nearly 2 thirds of the cases, which may have contributed to the low toxicity.

Dextromethorphan, however, stood out for its toxicity. Patients exposed to opioids (of which dextromethorphan was the drug most frequently involved) were more likely to have reached a toxic dose and developed more symptoms than the rest of patients. In addition, dextromethorphan was the drug involved in the 2 moderate to severe cases. On one hand, these differences can be attributed to the intrinsic toxicity of dextromethorphan, and on the other, to the availability of paediatric dosage forms with pleasant organoleptic characteristics that can deliver doses considered highly toxic to children with a body weight of 10 kg22.

Similarly, although the small sample size precluded reaching a statistically significant result, 5 of the 6 patients who ingested terbutaline exceeded the toxic threshold and developed symptoms. The characteristics of the preparations available in the market may also play a part in these results.

On the other hand, the higher frequency of electrocardiographic evaluation of patients who ingested terbutaline and antihistamines was associated with the known cardiotoxicity of antihistamines and sympathomimetic drugs29,30.

The Pediatric Cough and Cold Safety Surveillance System of the United States, which monitors the development of adverse events associated with these medications in children aged less than 12 years, identified 5342 cases between 2008 and 20149. A more recent study of the data obtained by the same system found that despite the efforts made in the past few decades to reduce the incidence of paediatric poisonings, the adverse event case rate per 100 million cough and cold medication units sold remained stable between 2009 and 2016, while the frequency of related hospital admissions actually increased10.

Both the reviewed literature and the presented cases show that further efforts need to be made to prevent paediatric poisonings. Marketed preparations, especially those aimed at the paediatric population, must be improved, both in the amount of the active ingredient they contain and in the use of child-resistant packaging, which is a must.

Another relevant finding was that in nearly half the cases in the sample, the overdose occurred in a child undergoing treatment with the involved drug due to either a mistake in the administration by the caregivers or unsupervised ingestion by the child. Therefore, paediatricians should consider whether it is worth taking the risk of prescribing cough and cold medication in relation to its potential therapeutic benefits.

In general, the use of cough and cold medication is not recommended in paediatric clinical practice guidelines3,4. Several Cochrane reviews have concluded that these drugs should be avoided in children, as there is no evidence of their usefulness and they are potentially dangerous. This is the position held by De Sutter et al. in their review of antihistamine-decongestant combinations5, Gardiner et al. in their review of the use of codeine and its derivatives6 and of Smith et al. in their meta-analysis on the use of over the counter medications for acute cough in children and adults7. Notwithstanding, they are very accessible drugs, as they are sold over the counter and are even frequently prescribed by physicians2.

We also ought to mention that in half the cases in which the patient was undergoing treatment with cough and could medication, the age was outside the range established in the summary of product characteristics. Although the off-label use of medications is frequent in the paediatric population due to the lack of specific clinical trials in this age group31–33, it is not always appropriate or adequately documented, as evinced by the recent article by Piñeiro-Pérez et al33. In the case of cough and could medication, off-label use is even harder to justify, given the doubtful efficacy evinced to date and the risk of toxicity.

Dosing errors caused nearly one fourth of the episodes and were associated with greater delays in seeking care (probably associated with the time it took caregivers to become aware the mistake) and a decreased opportunity for intervention. In our sample, we did not find cases of moderate or severe poisoning caused by this mechanism. However, between 2009 and 2016, the Pediatric Cough and Cold Safety Surveillance System identified 513 cases in which adverse events occurred following errors in the administration of cough and cold medication, of which 25% required hospital admission and 10% admission to an intensive care unit. In agreement with our results, dextromethorphan and diphenhydramine were the drugs most frequently involved in these episodes34.

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design, due to the loss of data it entails. The presence of a specific template for the anamnesis of poisoned patients reduces this risk, but it is possible that health records did not document the use of the drug as an established treatment, so the corresponding frequency may have been underestimated. We were also unable to determine in which case the drug had been prescribed by a physician or acquired over the counter.

Despite these limitations, the study identified some aspects that facilitate poisoning with cold and cough medication in the paediatric population. First of all, the prescription of potentially toxic drugs that are of limited utility and, secondly, the frequency of errors in their administration, probably due to the lack of a clear prescription in writing. Other factors that may be at play are the possibility of obtaining these drugs without a prescription, independently of the age of the child, and inadequate implementation of measures for the safe storage of medicines in the home.

In conclusion, our study showed that although the current evidence does not support the use of cold medicines in children, unintentional poisonings with these drugs continue to occur, in some cases moderate or severe. To reduce this risk, strategies must be developed to achieve the following goals: 1- Reducing the prescription of these drugs to paediatric patients; 2- In the case of over-the-counter dispensation, providing information on the risk of poisoning and the age limit established in the summary of product characteristics; 3- Promoting the use of child-resistant packaging in all paediatric preparations, and 4- Improving health education for families to reduce children’s unsupervised access to drugs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Previous presentation: Preliminary data of this study were presented at the XXIV Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, held in Murcia, Spain in May 2019, and at the XXIII Jornadas de Toxicología Clínica, held in Valencia in November 2019.