Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is an acute and severe disease that is rare in paediatrics (0.5/100,000 inhabitants). It is characterised by fever, exanthema, hypotension and multiple organ failure, and caused by infection by toxin-producing bacteria. Although Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most frequently involved in TSS,1,2 erythrogenic toxin-producing streptococci (mainly Streptococcus pyogenes) are currently responsible for a large number of cases. Despite its considerable morbidity and mortality, few studies have analysed the incidence, manifestations, treatment and complications of this disease in the paediatric age group.1

With the purpose of describing the aetiology and clinical and laboratory characteristics of cases of TSS in the PICU of a tertiary-level hospital in recent years, we conducted a retrospective descriptive study between January 2001 and December 2015. We included patients that met the clinical and microbiological criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the diagnosis of staphylococcal and streptococcal TSS. We collected epidemiological, clinical, microbiological and laboratory data pertaining to PICU admission and outcomes. We present the data as frequencies, percentages, mean (range) and median (interquartile range [IQR]).

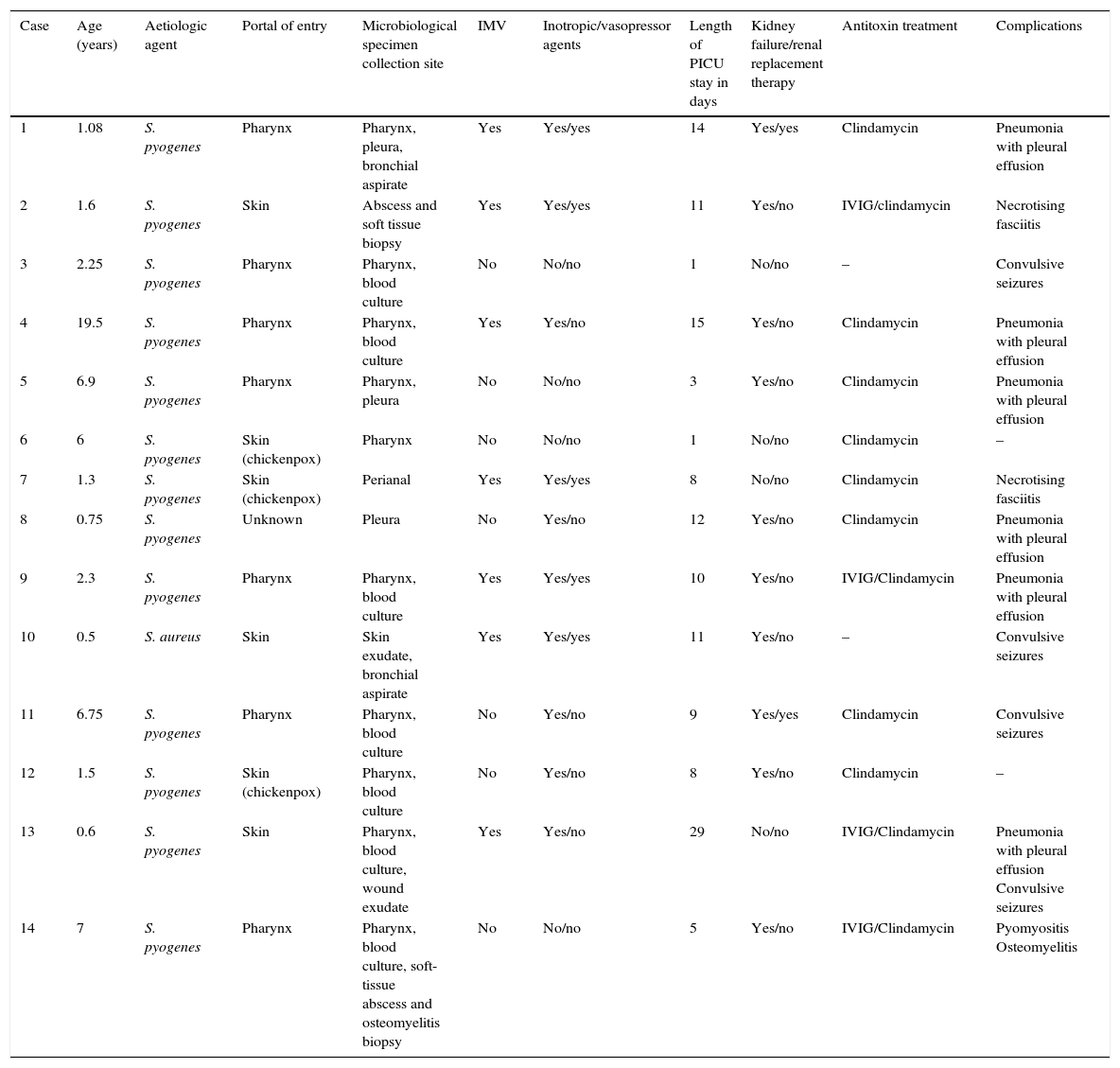

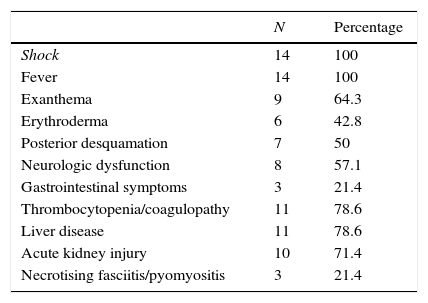

There were 14 cases of TSS (Table 1), 50% in male patients, and the median age was 1.9 years (0.9–6.7). Thirteen patients met the diagnostic criteria for streptococcal TSS (11 cases confirmed with isolation of S. pyogenes from normally sterile sites, and 2 probable cases with isolation from non-sterile sites) and TSS was caused by S. aureus in only one patient. The portal of entry was the pharynx in 7 cases, the skin in 6 (3 due to superinfection of lesions caused by varicella) and unknown in 1. All patients developed fever, hypotension and failure of 2 or more organs (Table 2), 8 (57.1%) had decreased level of consciousness or lethargy, and 21.4% had gastrointestinal symptoms. Exanthema developed in 64.3% of the patients (generalised erythematous rash in 6, and macular morbilliform rash in 3), with delayed desquamation in 7 patients.

Patient characteristics: age, microbial isolation, need for mechanical ventilation and inotropic treatment, length of stay in PICU, associated kidney failure and need for renal replacement therapy, antitoxin treatment and developed complications.

| Case | Age (years) | Aetiologic agent | Portal of entry | Microbiological specimen collection site | IMV | Inotropic/vasopressor agents | Length of PICU stay in days | Kidney failure/renal replacement therapy | Antitoxin treatment | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.08 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, pleura, bronchial aspirate | Yes | Yes/yes | 14 | Yes/yes | Clindamycin | Pneumonia with pleural effusion |

| 2 | 1.6 | S. pyogenes | Skin | Abscess and soft tissue biopsy | Yes | Yes/yes | 11 | Yes/no | IVIG/clindamycin | Necrotising fasciitis |

| 3 | 2.25 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, blood culture | No | No/no | 1 | No/no | – | Convulsive seizures |

| 4 | 19.5 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, blood culture | Yes | Yes/no | 15 | Yes/no | Clindamycin | Pneumonia with pleural effusion |

| 5 | 6.9 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, pleura | No | No/no | 3 | Yes/no | Clindamycin | Pneumonia with pleural effusion |

| 6 | 6 | S. pyogenes | Skin (chickenpox) | Pharynx | No | No/no | 1 | No/no | Clindamycin | – |

| 7 | 1.3 | S. pyogenes | Skin (chickenpox) | Perianal | Yes | Yes/yes | 8 | No/no | Clindamycin | Necrotising fasciitis |

| 8 | 0.75 | S. pyogenes | Unknown | Pleura | No | Yes/no | 12 | Yes/no | Clindamycin | Pneumonia with pleural effusion |

| 9 | 2.3 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, blood culture | Yes | Yes/yes | 10 | Yes/no | IVIG/Clindamycin | Pneumonia with pleural effusion |

| 10 | 0.5 | S. aureus | Skin | Skin exudate, bronchial aspirate | Yes | Yes/yes | 11 | Yes/no | – | Convulsive seizures |

| 11 | 6.75 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, blood culture | No | Yes/no | 9 | Yes/yes | Clindamycin | Convulsive seizures |

| 12 | 1.5 | S. pyogenes | Skin (chickenpox) | Pharynx, blood culture | No | Yes/no | 8 | Yes/no | Clindamycin | – |

| 13 | 0.6 | S. pyogenes | Skin | Pharynx, blood culture, wound exudate | Yes | Yes/no | 29 | No/no | IVIG/Clindamycin | Pneumonia with pleural effusion Convulsive seizures |

| 14 | 7 | S. pyogenes | Pharynx | Pharynx, blood culture, soft-tissue abscess and osteomyelitis biopsy | No | No/no | 5 | Yes/no | IVIG/Clindamycin | Pyomyositis Osteomyelitis |

IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

Clinical presentation and associated organ injury.

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Shock | 14 | 100 |

| Fever | 14 | 100 |

| Exanthema | 9 | 64.3 |

| Erythroderma | 6 | 42.8 |

| Posterior desquamation | 7 | 50 |

| Neurologic dysfunction | 8 | 57.1 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 3 | 21.4 |

| Thrombocytopenia/coagulopathy | 11 | 78.6 |

| Liver disease | 11 | 78.6 |

| Acute kidney injury | 10 | 71.4 |

| Necrotising fasciitis/pyomyositis | 3 | 21.4 |

Ten patients (71.4%) required vasoactive support, including administration of vasopressors in 5 patients for a mean of 6.2 days (2–12), and with a mean vasoactive-inotropic score of 42. Nine out of the 14 patients required ventilatory support, 7 with intubation (mean duration, 10 days; range, 6–25) and 2 with noninvasive mechanical ventilation (mean duration, 2.5 days). Some of the findings compatible with multiple organ failure were: thrombocytopenia and/or coagulopathy as well as abnormal liver function test results in 11 patients (78.6%); hypocalcaemia in 5 (35.7%); acute kidney injury in 10 (71.4%), 2 of whom required renal replacement therapy for a mean of 4 days. Three patients developed soft-tissue necrosis in the form of necrotising fasciitis or pyomyositis that required surgical debridement.

In 12 out of the 13 cases of streptococcal TSS, clindamycin was added to the initial treatment with cefotaxime. Four patients received immunoglobulin therapy (3 with necrotising fasciitis or pyomyositis) and 2 received steroid therapy. The patient with staphylococcal infection initially received cefotaxime, followed by cloxacillin. All patients had favourable outcomes, and none died. Close contacts and household members did not receive prophylactic antibiotherapy in any case, and there was no documentation of any associated events.

Our study reflects the severity of the illness developed by these patients, with a large proportion requiring advanced haemodynamic and respiratory support.1 Most patients were less than 2 years of age, which was consistent with other series.3 The most frequent portals of entry were the pharynx and the skin, and varicella infection was a significant risk factor, consistent with the literature.1 Ninety-three percent of cases were caused by S. pyogenes, which diverges from previous studies conducted in Spain and recent international publications, in which S. aureus continues to be the most prevalent causative agent.1,2

Although streptococcal TSS is associated with a high mortality of up to 30–60% compared to 5% in staphylococcal TSS,1,3–5 there were no deaths in our case series, probably due to the early initiation of treatment. The administration of prophylactic antibiotics to close contacts remains controversial, and is recommended in a few countries, such as Canada.6

It is crucial that this condition is detected early and the patient referred to a facility with intensive care services.1,5 When TSS is suspected, the patient should be placed on life support, as would be done in cases of septic shock, with the addition of antitoxin treatment (antimicrobials such as clindamycin), surgical debridement, and administration of immunoglobulin to enhance plasma neutralising activity against toxins.6

Please cite this article as: Butragueño Laiseca L, García Morín M, Barredo Valderrama E, Alcaraz Romero AJ. Síndrome de shock tóxico en una unidad de cuidados intensivos pediátricos en los últimos 15 años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:111–113.