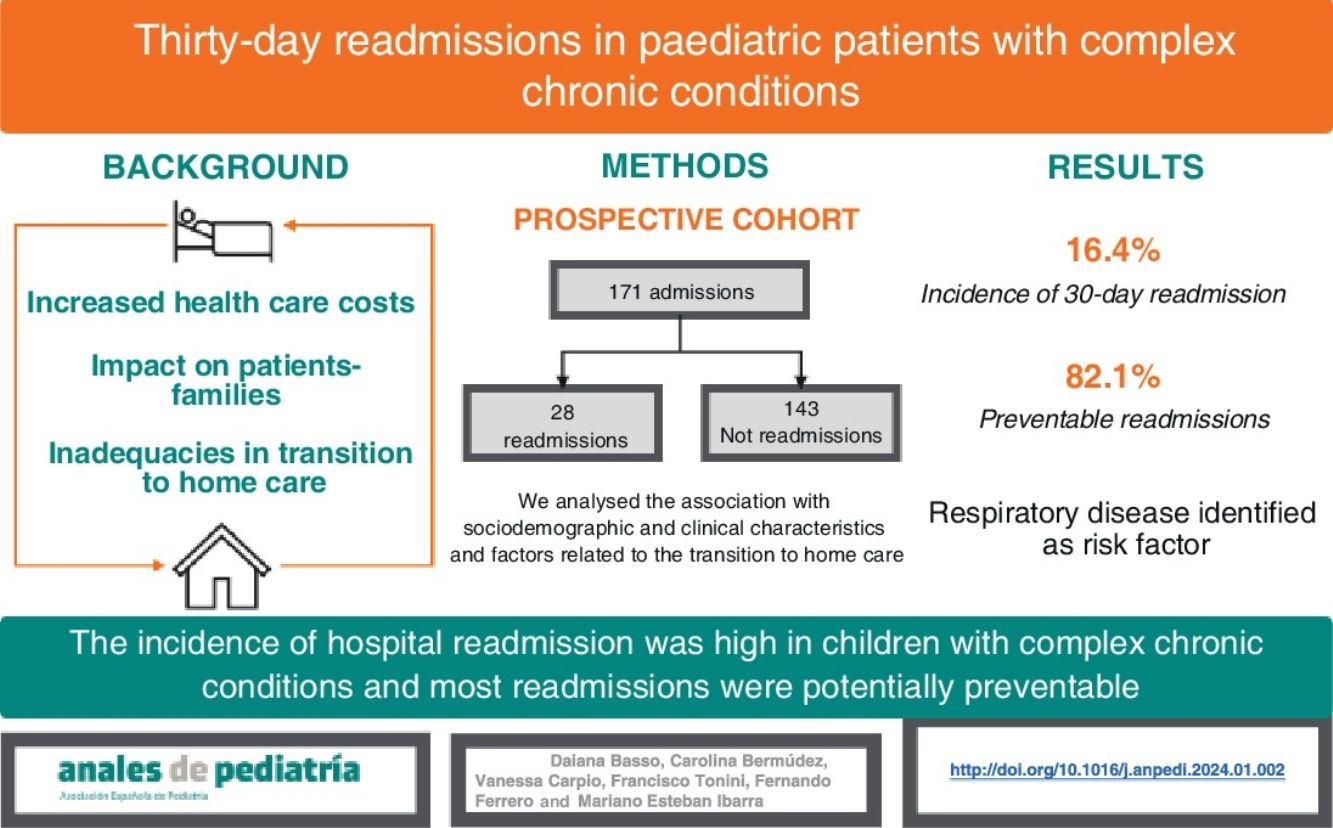

The rate of hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge is a quality indicator in health care. Paediatric patients with complex chronic conditions have high readmission rates. Failure in the transition between hospital and home care could explain this phenomenon.

ObjectivesTo estimate the incidence rate of 30-day hospital readmission in paediatric patients with complex chronic conditions, estimate how many are potentially preventable and explore factors associated with readmission.

Materials and methodCohort study including hospitalised patients with complex chronic conditions aged 1 month to 18 years. Patients with cancer or with congenital heart disease requiring surgical correction were excluded. The outcomes assessed were 30-day readmission rate and potentially preventable readmissions. We analysed sociodemographic, geographic, clinical and transition to home care characteristics as factors potentially associated with readmission.

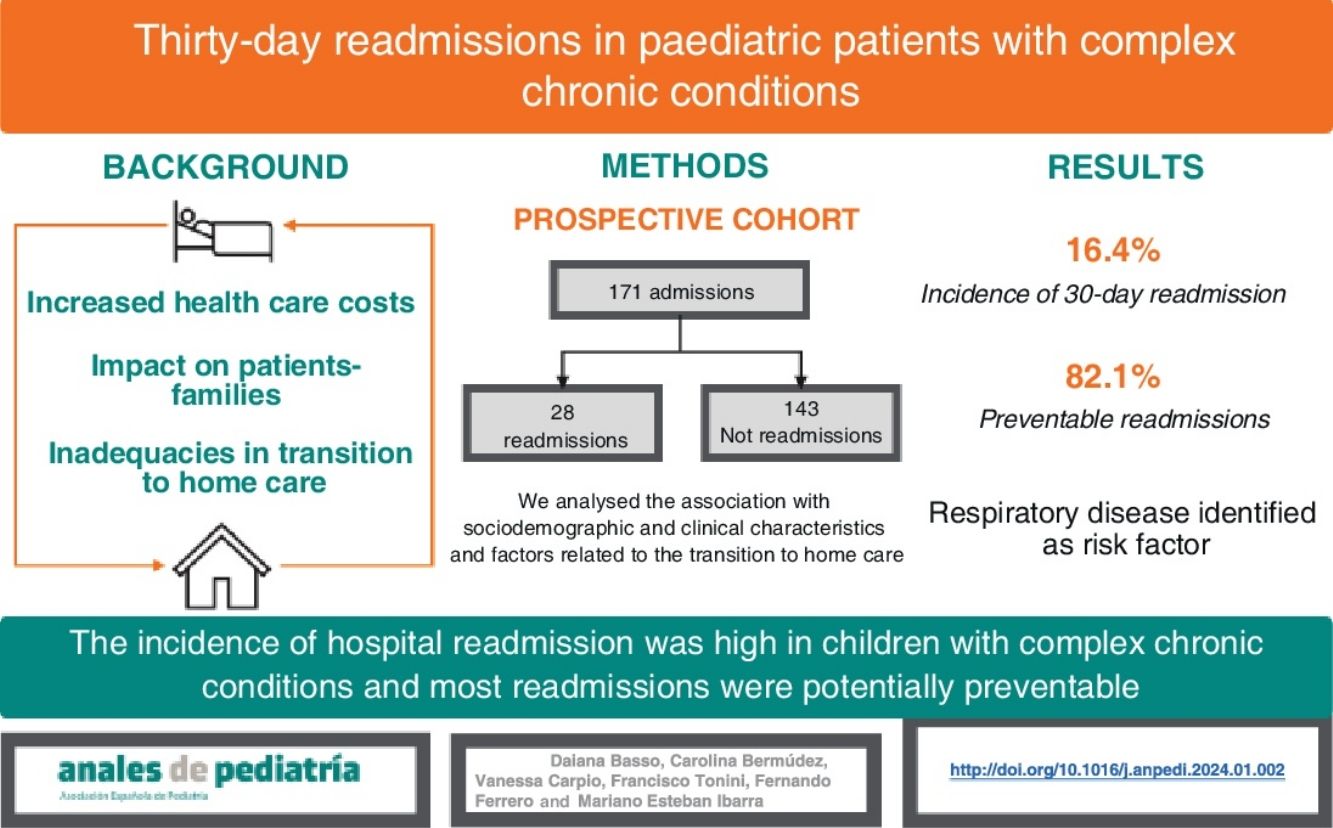

ResultsThe study included 171 hospitalizations, and 28 patients were readmitted within 30 days (16.4%; 95% CI, 11.6%–22.7%). Of the 28 readmissions, 23 were potentially preventable (82.1%; 95% CI, 64.4%–92.1%). Respiratory disease was associated with a higher probability of readmission. There was no association between 30-day readmission and the characteristics of the transition to home care.

ConclusionsThe 30-day readmission rate in patients with complex chronic disease was 16.4%, and 82.1% of readmissions were potentially preventable. Respiratory disease was the only identified risk factor for 30-day readmission.

La tasa de reingreso hospitalario a 30 días del alta es una medida de calidad de atención médica. Los pacientes pediátricos con patologías crónicas complejas tienen altas tasas de reingreso. La falla en la transición entre el cuidado hospitalario y domiciliario podría explicar este fenómeno.

ObjetivosEstimar la tasa de incidencia de reingreso hospitalario a 30 días en pacientes pediátricos con patologías crónicas complejas, estimar cuántos son potencialmente prevenibles y explorar posibles factores asociados a reingreso.

Materiales y métodoEstudio de cohorte prospectivo incluyendo pacientes hospitalizados con patologías crónicas complejas de 1 mes a 18 años de edad. Se excluyeron pacientes con patología oncológica y cardiopatías congénitas. Se evaluaron el reingreso a 30 días y el reingreso potencialmente prevenible. Se valoraron características sociodemográficas, geográficas, clínicas y de la transición hacia el cuidado domiciliario.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 171 hospitalizaciones; dentro de los 30 días reingresaron 28 pacientes (16,4 %; IC95% 11,6–22,7). De los 28 reingresos, 23, (82,1 %; IC95% 64,4–92,1) fueron potencialmente prevenibles. La patología respiratoria se asoció con mayor probabilidad de reingreso. No se encontró asociación entre reingreso a 30 días y los factores de la transición al cuidado domiciliario evaluados.

ConclusionesLa tasa de reingreso a 30 días en pacientes con patología crónica compleja fue de 16,4 %, y el 82,1 % fueron potencialmente prevenibles. Únicamente la patología respiratoria se comportó como factor de riesgo para reingreso a 30 días.

The rate of hospital readmission is a quality indicator in health care that has gained additional relevance since the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program established within the Affordable Care Act in the United States in 2012

Set financial incentives for hospitals that reduced the number of readmissions and penalties for those with excess readmissions.1,2 A 30-day readmission is defined as a return hospitalization of the patient within 30 days of discharge of a prior admission.3 Hospital readmissions increase health care costs4 and are associated with longer lengths of stay.5 Depending on the type of hospital and the population it serves, the readmission rate can range from 4.3%–19.6%.2

A previous study conducted in our hospital found that most potentially preventable readmissions occurred in patients with chronic conditions, who accounted for 73% of readmissions.6 This finding was consistent with other studies in which the proportion of readmissions corresponding to chronically ill patients ranged between 63% and 70% of the total.5,7 Within the group of patients with chronic conditions, there is a subset with chronic complex conditions (CCCs). The latter are defined as any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 organ system severely enough to require specialty paediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care centre.8 The number of patients with chronic conditions who are technology-dependent has increased drastically in recent years, with a substantial impact on health care costs.9,10 These patients are admitted and readmitted more frequently, require multiple drugs and need interdisciplinary management after discharge.11 However, few studies have studied this paediatric population in depth.

Despite efforts made on multiple fronts, recent studies have evinced the difficulty of reducing the overall readmission rate.12 One of possible explanations that has been proposed is that the proportion of preventable readmissions is overestimated, perhaps due to the mistaken assumption that any readmission for reasons related to the initial admission is potentially preventable.12 For this reason, some authors have suggested redirecting efforts to the most medically complex patients, a group with a higher frequency of readmission.10,12 Inadequacies in the hospital to home care transition have been proposed as a possible cause of these readmissions.13 At present, this stage of the care episode is considered a crucial juncture.

In light of the above, we believed it would be relevant to analyse the characteristics of the transition from hospital to at-home care in paediatric patients with CCCs and assess whether there are factors associated with an increased probability of 30-day readmission.

ObjectivesTo assess the 30-day readmission rate in paediatric patients with CCC and the proportion of potentially preventable readmissions. To explore factors potentially associated with 30-day readmission in paediatric patients with CCC.

Material and methodsWe conducted a prospective cohort study. The study was carried out at Hospital General de Niños Pedro de Elizade, a tertiary care children’s hospital serving the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, between October 1, 2021 and September 30, 2022.

Inclusion criteriaWe included admissions in the general paediatrics floor with delivery of general intensive care of patients aged 1 month to 18 years with CCC. Complex chronic condition was defined as any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or one organ system severely enough to require specialty paediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care center.8

Exclusion criteriaWe excluded admissions corresponding to patients transferred to other medical facilities or care facilities other than the home. We also excluded patients with cancer or congenital heart defects requiring surgical correction. These patients require specific follow-up and are hospitalised in specialised units that are beyond the scope of the study. We also decided to exclude from the analysis those eligible admissions in which the patient was lost to follow-up or died. We recruited patients using systematic random sampling with a random start number (k = 2).

Follow-upPatients were recruited during the initial hospital stay. After discharge, we performed follow-up phone calls for 40 days to identify readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge.

VariablesThe primary outcome of the study was the 30-day readmission rate. We also calculated the proportion of potentially preventable readmissions applying criteria of Goldfield et al. with modifications.3 The definition of potentially preventable readmission was an unplanned readmission considered clinically related to the previous admission due to one of the following: recurrence of the reason for the previous admission, acute decompensation of a chronic problem that may or may not have been the reason for the previous admission or admission due to an acute medical complication plausibly related to care during the previous admission.

We grouped the exploratory variables considered for the analysis of the care transition from the hospital to the home based on the concepts they represented: sociodemographic characteristics (age, biological sex, distance between home and hospital, means of transport, health care coverage, educational attainment of caregiver), clinical characteristics (classification of CCC diagnosis by involved organ system, technology dependence) and care transition from hospital to home (primary care paediatrician, length of stay in days, discharge during the weekend, number of medical follow-up visits scheduled at discharge and number of drugs prescribed at discharge).

Statistical analysisWe have expressed categorical variables as percentages with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and quantitative variables as median and range based on the observed distribution (not normal).

To identify factors associated with 30-day readmission, we assessed the association between the exploratory variables and the outcome variable by means of binary logistic regression analysis. We used the odds ratio (OR) as the measure of association. Last of all, since different variables may interact and that the analysis of the associated factors was exploratory, we fitted a multivariate logistic regression model. The variables included in this model were the ones that exhibited a significant association in the bivariate analysis. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of less than 0.05 in all the analyses.

We requested and obtained informed consent from the caregivers or the patients, depending on the level of autonomy of the latter. All the data were dissociated to safeguard the privacy of the patients. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital General de Niños Pedro de Elizalde, File no. 7147.

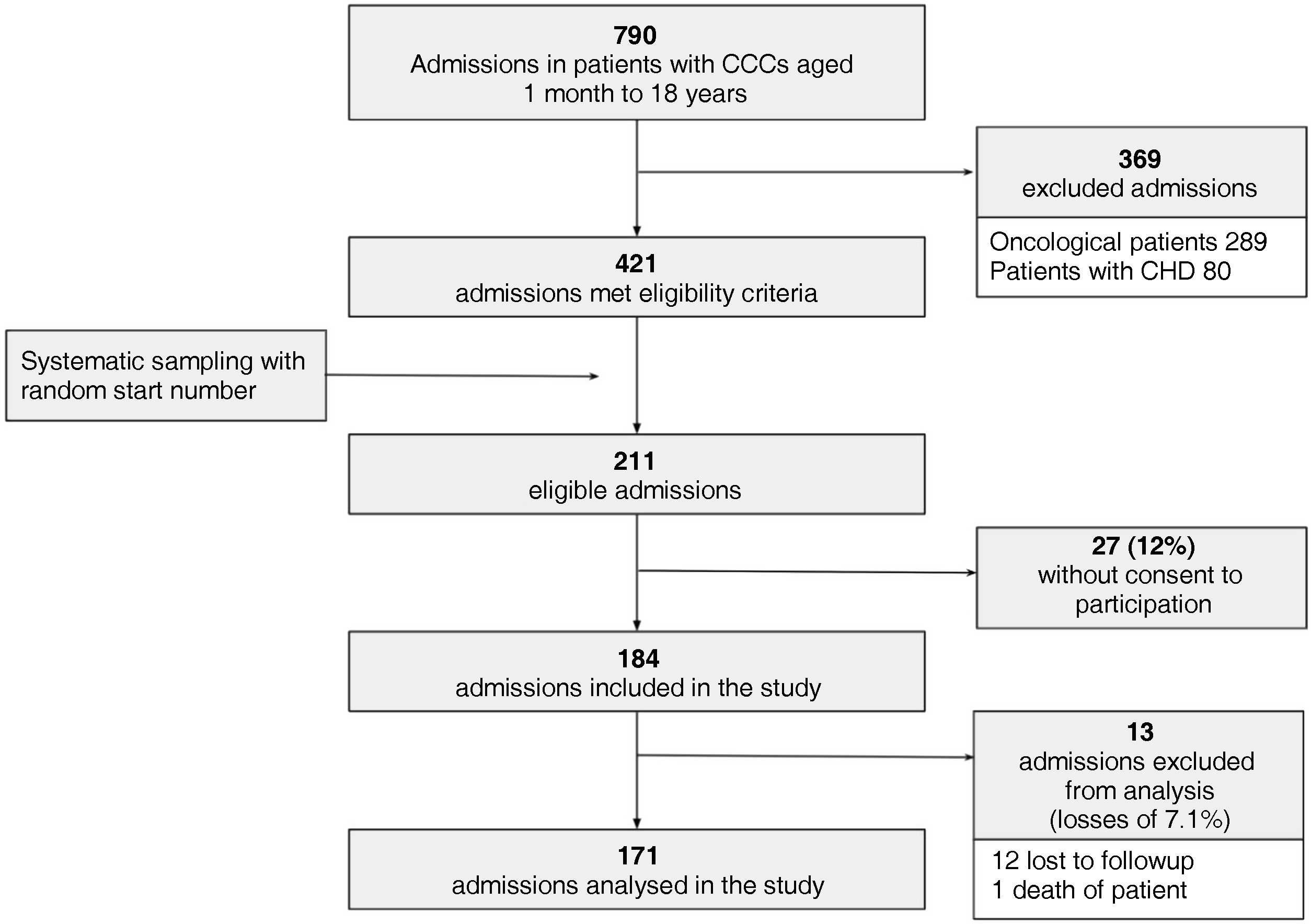

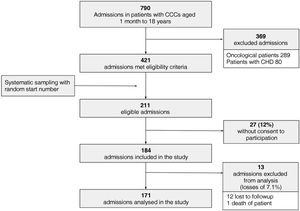

ResultsIn the period under study, 184 admissions met the inclusion criteria for which we obtained informed consent to participation. Of this total, we excluded 13 admissions due to loss to follow-up or death of the patient (losses of 7.1%), so the analysis included 171 admissions of patients with CCC (Fig. 1).

In the included sample of 171 admissions, there were 28 patients readmitted within 30 days, corresponded to a readmission rate of 16.4% (95% CI, 11.6%–22.7%). Of the 28 readmissions, 23 were potentially preventable (82.1%; 95% CI, 64.4%–92.1%).

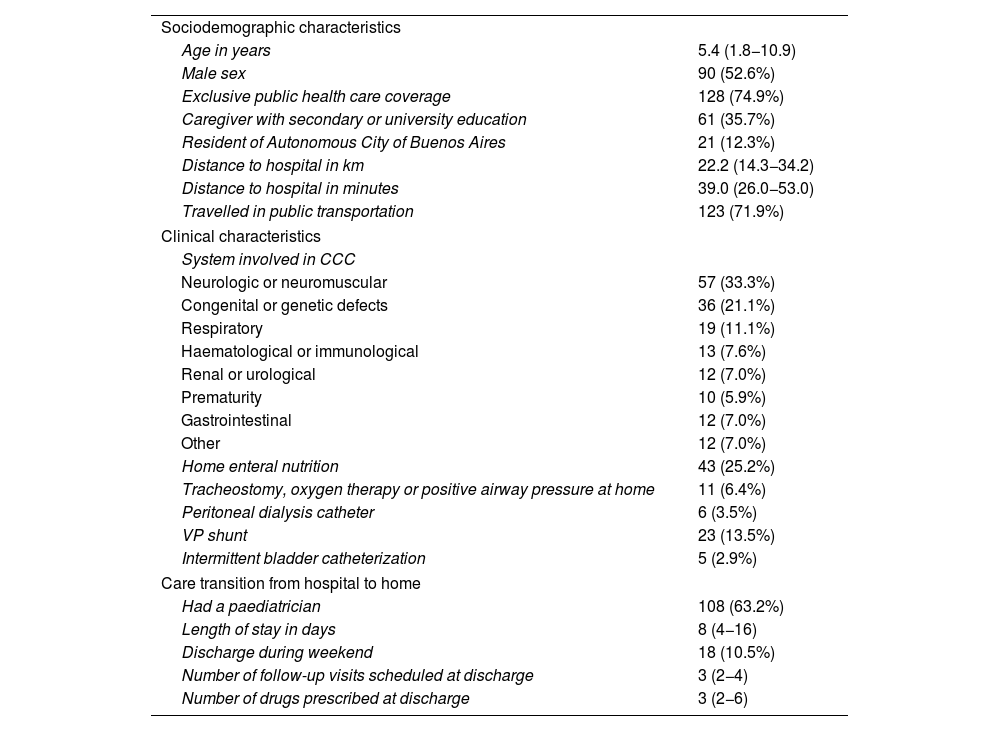

As regards the characteristics of the admissions (Table 1), the median age of the patients was 5.4 years (1.8−10.9), 52.6% were male, and there was a predominance of CCC of a neurologic or neuromuscular nature (33.3%), resulting from congenital or genetic defects (21.1%) and involving the respiratory system (11.1%).

Characteristics of admissions (n = 171).

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Age in years | 5.4 (1.8−10.9) |

| Male sex | 90 (52.6%) |

| Exclusive public health care coverage | 128 (74.9%) |

| Caregiver with secondary or university education | 61 (35.7%) |

| Resident of Autonomous City of Buenos Aires | 21 (12.3%) |

| Distance to hospital in km | 22.2 (14.3−34.2) |

| Distance to hospital in minutes | 39.0 (26.0−53.0) |

| Travelled in public transportation | 123 (71.9%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| System involved in CCC | |

| Neurologic or neuromuscular | 57 (33.3%) |

| Congenital or genetic defects | 36 (21.1%) |

| Respiratory | 19 (11.1%) |

| Haematological or immunological | 13 (7.6%) |

| Renal or urological | 12 (7.0%) |

| Prematurity | 10 (5.9%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 12 (7.0%) |

| Other | 12 (7.0%) |

| Home enteral nutrition | 43 (25.2%) |

| Tracheostomy, oxygen therapy or positive airway pressure at home | 11 (6.4%) |

| Peritoneal dialysis catheter | 6 (3.5%) |

| VP shunt | 23 (13.5%) |

| Intermittent bladder catheterization | 5 (2.9%) |

| Care transition from hospital to home | |

| Had a paediatrician | 108 (63.2%) |

| Length of stay in days | 8 (4−16) |

| Discharge during weekend | 18 (10.5%) |

| Number of follow-up visits scheduled at discharge | 3 (2−4) |

| Number of drugs prescribed at discharge | 3 (2−6) |

We have expressed categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as median and interquartile range.

CCC, chronic complex condition; VP, ventriculoperitoneal.

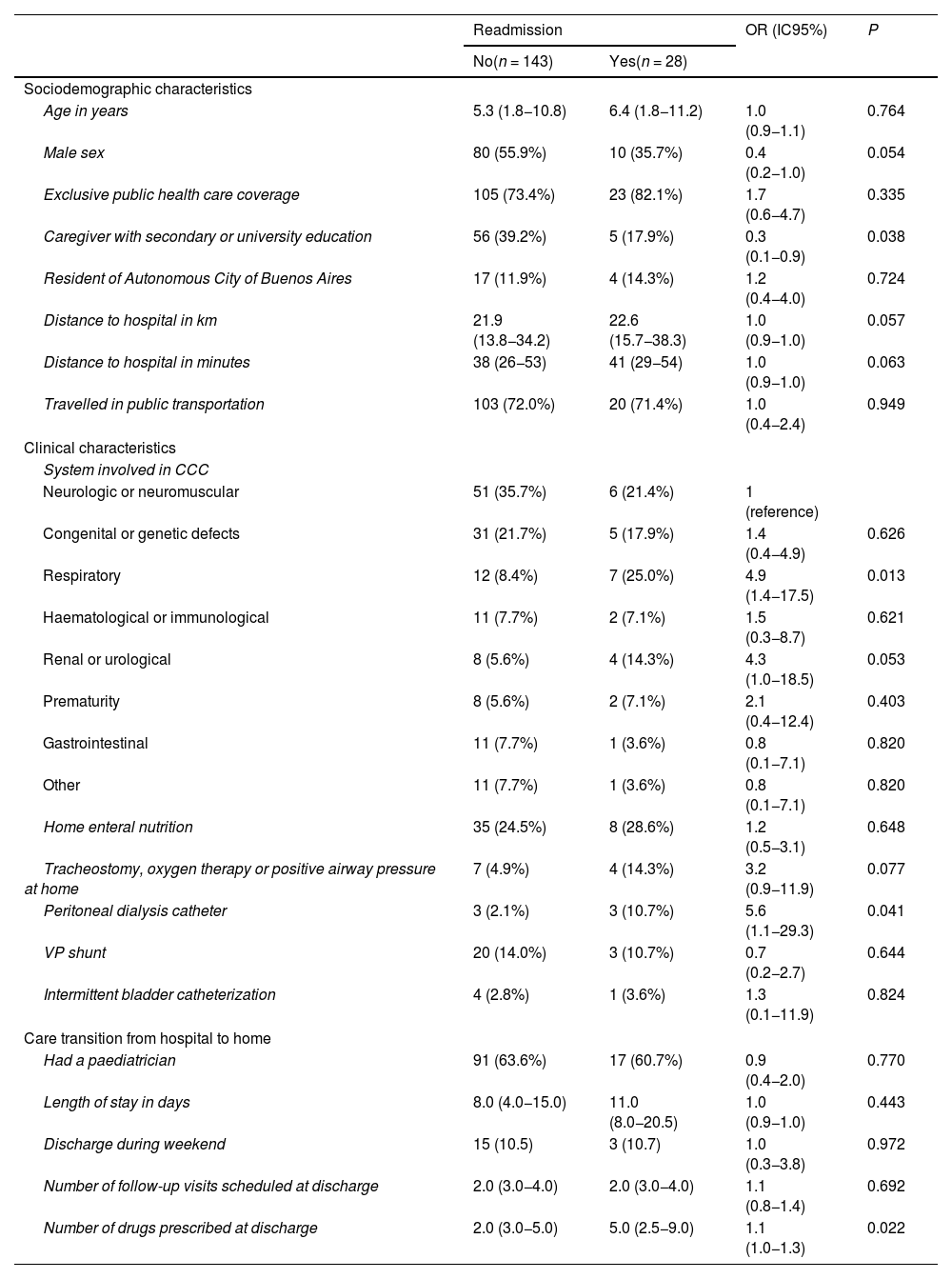

In the bivariate analysis, an educational attainment at the level of secondary education or university in the caregiver acted as a protective factor against 30-day readmission (OR, 0.3, 95% CI, 0.1−0.9; P = 0.038). Chronic disease involving the respiratory system, requiring a peritoneal dialysis catheter and the number of drugs prescribed at discharge were risk factors for 30-days readmission (ORs of 4.9, 5.6 and 1.1, respectively) (Table 2).

Possible risk factors for readmission.

| Readmission | OR (IC95%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No(n = 143) | Yes(n = 28) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age in years | 5.3 (1.8−10.8) | 6.4 (1.8−11.2) | 1.0 (0.9−1.1) | 0.764 |

| Male sex | 80 (55.9%) | 10 (35.7%) | 0.4 (0.2−1.0) | 0.054 |

| Exclusive public health care coverage | 105 (73.4%) | 23 (82.1%) | 1.7 (0.6−4.7) | 0.335 |

| Caregiver with secondary or university education | 56 (39.2%) | 5 (17.9%) | 0.3 (0.1−0.9) | 0.038 |

| Resident of Autonomous City of Buenos Aires | 17 (11.9%) | 4 (14.3%) | 1.2 (0.4−4.0) | 0.724 |

| Distance to hospital in km | 21.9 (13.8−34.2) | 22.6 (15.7−38.3) | 1.0 (0.9−1.0) | 0.057 |

| Distance to hospital in minutes | 38 (26−53) | 41 (29−54) | 1.0 (0.9−1.0) | 0.063 |

| Travelled in public transportation | 103 (72.0%) | 20 (71.4%) | 1.0 (0.4−2.4) | 0.949 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| System involved in CCC | ||||

| Neurologic or neuromuscular | 51 (35.7%) | 6 (21.4%) | 1 (reference) | |

| Congenital or genetic defects | 31 (21.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | 1.4 (0.4−4.9) | 0.626 |

| Respiratory | 12 (8.4%) | 7 (25.0%) | 4.9 (1.4−17.5) | 0.013 |

| Haematological or immunological | 11 (7.7%) | 2 (7.1%) | 1.5 (0.3−8.7) | 0.621 |

| Renal or urological | 8 (5.6%) | 4 (14.3%) | 4.3 (1.0−18.5) | 0.053 |

| Prematurity | 8 (5.6%) | 2 (7.1%) | 2.1 (0.4−12.4) | 0.403 |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (7.7%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.8 (0.1−7.1) | 0.820 |

| Other | 11 (7.7%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.8 (0.1−7.1) | 0.820 |

| Home enteral nutrition | 35 (24.5%) | 8 (28.6%) | 1.2 (0.5−3.1) | 0.648 |

| Tracheostomy, oxygen therapy or positive airway pressure at home | 7 (4.9%) | 4 (14.3%) | 3.2 (0.9−11.9) | 0.077 |

| Peritoneal dialysis catheter | 3 (2.1%) | 3 (10.7%) | 5.6 (1.1−29.3) | 0.041 |

| VP shunt | 20 (14.0%) | 3 (10.7%) | 0.7 (0.2−2.7) | 0.644 |

| Intermittent bladder catheterization | 4 (2.8%) | 1 (3.6%) | 1.3 (0.1−11.9) | 0.824 |

| Care transition from hospital to home | ||||

| Had a paediatrician | 91 (63.6%) | 17 (60.7%) | 0.9 (0.4−2.0) | 0.770 |

| Length of stay in days | 8.0 (4.0−15.0) | 11.0 (8.0−20.5) | 1.0 (0.9−1.0) | 0.443 |

| Discharge during weekend | 15 (10.5) | 3 (10.7) | 1.0 (0.3−3.8) | 0.972 |

| Number of follow-up visits scheduled at discharge | 2.0 (3.0−4.0) | 2.0 (3.0−4.0) | 1.1 (0.8−1.4) | 0.692 |

| Number of drugs prescribed at discharge | 2.0 (3.0−5.0) | 5.0 (2.5−9.0) | 1.1 (1.0−1.3) | 0.022 |

We have expressed categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as median and interquartile range.

CCC, chronic complex condition; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; VP, ventriculoperitoneal.

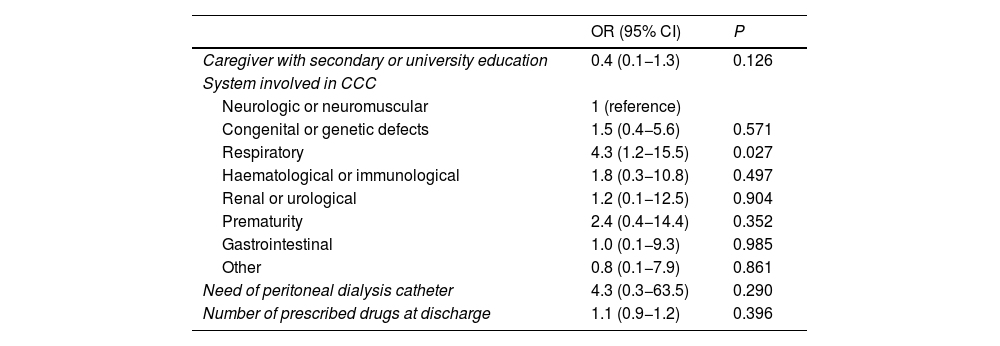

The multivariate analysis included every variable with a significant association in the bivariate analysis. Only CCC involving the respiratory system behaved as a risk factor for 30-day readmission (OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2−15.5; P = 0.027). On the other hand, none of the variables regarding the transition to home care was associated with 30-day readmission (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of the risk factors for readmission (n = 171).

| OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver with secondary or university education | 0.4 (0.1−1.3) | 0.126 |

| System involved in CCC | ||

| Neurologic or neuromuscular | 1 (reference) | |

| Congenital or genetic defects | 1.5 (0.4−5.6) | 0.571 |

| Respiratory | 4.3 (1.2−15.5) | 0.027 |

| Haematological or immunological | 1.8 (0.3−10.8) | 0.497 |

| Renal or urological | 1.2 (0.1−12.5) | 0.904 |

| Prematurity | 2.4 (0.4−14.4) | 0.352 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.0 (0.1−9.3) | 0.985 |

| Other | 0.8 (0.1−7.9) | 0.861 |

| Need of peritoneal dialysis catheter | 4.3 (0.3−63.5) | 0.290 |

| Number of prescribed drugs at discharge | 1.1 (0.9−1.2) | 0.396 |

CCC, chronic complex condition; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

This prospective cohort study in patients with CCC analysed the incidence of 30-day readmissions and the proportion of potentially preventable readmissions. Both were greater than the corresponding frequencies in the general paediatric inpatient population found in a previous study in the same hospital.6

The incidence of 30-day readmission in patients with CCCs was 16.4%. It was lower than the rate calculated by Jurgens et al. (19%)10 and by Dunbar et al. (19.8%–34.6%)14 in hospitals in the United States. This difference may be due to the characteristics of the populations under study. In the United States, readmissions are frequent in patients with sickle cell anaemia,10 whereas none of the readmissions in our study was associated with this disease. Furthermore, we excluded patients with cancer or cardiovascular disease requiring surgical correction from our study, whereas the studies by Jurgens et al. and Dunbar et al. included these patients. Patients with cancer or congenital heart disease are particularly likely to be readmitted,7 which could explain the higher readmission rates reported by these authors.

Of all readmissions, 82.1% were potentially preventable based on the modified Goldfield criteria.3 This was double the proportion reported in other studies conducted in the general paediatric population (that is, in which having a CCC was not an inclusion criterion) in Argentina6 and in Spain.5 This difference could be due to CCC and the associated increase in morbidity. One criterion used to define potentially preventable readmission is for the return admission to be related to the previous hospitalization or the underlying disease of the patient.3 We believe that this definition may be inadequate, as it is not enough for the reason for readmission to be related to the CCC diagnosis to determine whether a readmission was preventable. Not all complications or exacerbations associated with a CCC are preventable. The current criteria overestimate the preventability of readmissions.

In regard to the associated risk factors, the only one of the variables analysed in our study associated with a greater probability of readmission was respiratory CCC. It is common for these patients to experience exacerbations of disease resulting in readmission.15,16

We did not find a statistically significant association between 30-day readmission and the factors related to the transition to home care analysed in the study: distance between hospital and home, having a paediatrician, number of follow-up visits scheduled at discharge and prescribed drugs at discharge. Perhaps this is because in our hospital, patients receive a care plan as part of the discharge process that is updated during outpatient follow-up visits. Based on the previous evidence, this could reduce the probability of readmission.17,18 In a study conducted in the United States, de Jong et al. achieved a reduction in the rate of readmission from 10.3% to 7.4% with an intervention bundle based on planning follow-up care, medication reconciliation and screening and intervention for adverse social determinants of health.19

We should mention some limitations to our study that may affect the generalization of its findings. It included patients with CCCs managed in a single hospital in the public health system residing in the southern metropolitan area of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, who therefore had a particular sociodemographic profile. However, it is such sectors of the population that tend to be understudied, which may make this information particularly valuable. Another limitation is that we did not interview caregivers to establish the collection of circumstances leading to the readmission of the patients. The objectives did not include an analysis of the time elapsed from discharge to readmission, although there is evidence that readmissions closer to the date of discharge are more likely to be preventable.7,12 The main strength of our study was its prospective design, as most studies on the subject are retrospective and have the intrinsic limitations of using secondary data.10,14

Last of all, we ought to highlight that the patients under study constitute a relatively homogeneous population in which the different factors evaluated in our study were not associated with an increased probability of readmission, except for CCC involving the respiratory system. In addition, while the current criteria to define the preventability of readmission are clearly limited, the proportion of potentially preventable readmissions was very high. Based on all of the above, qualitative studies need to be performed to explore the perspectives of patients and families to identify challenges that can be subject to intervention and develop prevention strategies followed by monitoring their impact on the rare of readmission.

ConclusionThe 30-day readmission rate in patients with CCC was 16.4%, and 82.1% of readmissions met the criteria for being potentially preventable. Respiratory disease was the only identified risk factor for 30-day readmission.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.