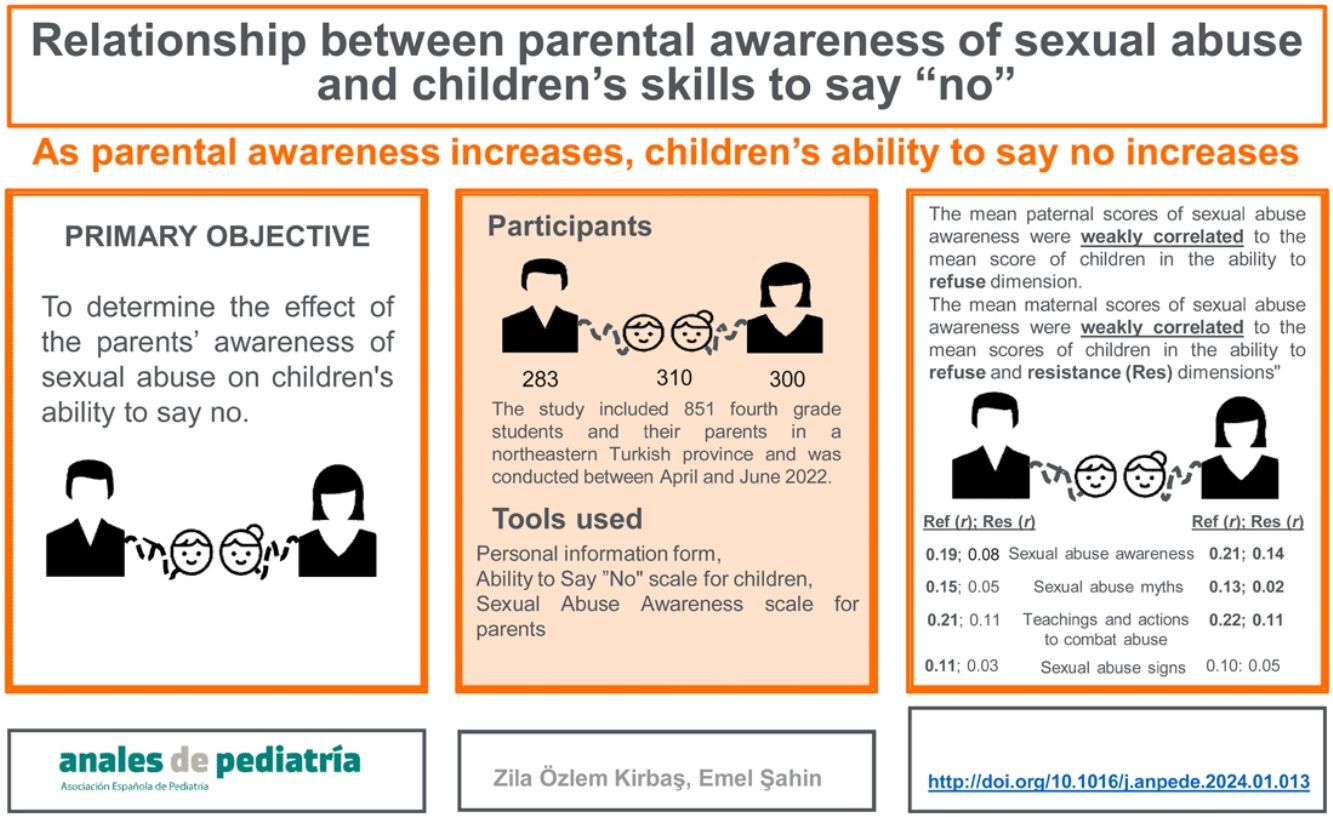

Child sexual abuse is a global and multidimensional social problem and causes devastating and permanent psychological, emotional, cognitive, behavioural, physical, sexual and interpersonal sequelae. This study examines the relationship between the ability to say “no” and parental awareness of sexual abuse in 4th grade primary school students.

MethodsThe study was conducted between April 2022 and June 2022 in primary schools in the central district of a province in north-eastern Turkey. The sample consisted of 310 students enrolled in 4th grade and their parents. We collected the data through a personal information form, the Ability to Say “No” Scale for Children and the Sexual Abuse Awareness Scale for Parents.

ResultsThere was a weak positive correlation between the mean maternal scores of sexual abuse awareness and the mean scores of refusal and resistance in children (P < .05), as well as a weak positive correlation between the mean paternal scores of sexual abuse awareness and the mean scores of refusal and resistance in children (P < .05).

ConclusionAs mothers’ and fathers’ awareness of sexual abuse myths and of teachings and actions to combat sexual abuse increased, the refusal of children also increased. Also, as fathers’ awareness of the signs of sexual abuse increased, children’s refusal increased.

El abuso sexual infantil es un problema social global y multidimensional que provoca resultados devastadores y permanentes en las relaciones psicológicas, emocionales, cognitivas, conductuales, físicas, sexuales e interpersonales. Este estudio examina la relación entre la capacidad de decir "no" y la conciencia de madres y padres sobre el abuso sexual en estudiantes de 4º de primaria.

MétodosEl estudio se realizó entre abril de 2022 y junio de 2022 en escuelas primarias de un distrito central provincial en el noreste de Turquía. La muestra del estudio estuvo formada por 310 alumnos de 4º de primaria y sus madres y padres. Compilamos los datos del estudio con el Formulario de Información Personal, la Escala de Capacidad para Decir “No” para Niños y la Escala de Conciencia de Abuso Sexual para Padres.

ResultadosHubo una correlación positiva débil (p<0,05) entre las puntuaciones medias de conciencia de las madres sobre el abuso sexual y las puntuaciones medias de rechazo y resistencia de los niños, una correlación positiva débil (p<0,05) entre las puntuaciones medias de la conciencia de los padres sobre el abuso sexual y las puntuaciones medias de rechazo de los niños.

ConclusiónA medida que aumentó la conciencia de los madres y padres sobre los mitos y las enseñanzas sobre el abuso sexual y las acciones para combatir el abuso sexual, también aumentó la negativa de los niños. Se encontró que a medida que aumentaba la conciencia de los padres sobre las señales de abuso sexual, aumentaba la negativa de los niños.

The numerous short- and long-term negative consequences associated with child sexual abuse (CSA) and its high prevalence make its prevention a societal priority.1–4 There is evidence that parents play an important role in preventive efforts against child sexual abuse.5 It is important to teach children self-protection skills and how to have healthy and respectful relationships.6,7

Different measures need to be taken to protect children from sexual abuse. One of them is to ensure they have the ability to say “no” to sexual abuse.8 When it comes to sexual abuse, one consideration is whether the child is or is not able to say “no”.9 According to Sanderson, children can protect themselves if they are informed about the dangers of sexual abuse, given permission to resist and provided with information on how to resist. Saying “no” loud and clear is a possible strategy for refusal, resistance or escape.10 It is known that children who exhibit timid attitudes and, most importantly, do not know how to say “no”, are unable to ask for help from another person or escape the situation when faced with the threat of abuse.11 In a study conducted in Nigeria, almost all parents informed their children that if someone wanted to see or touch their private parts, they should say “no” (98%) and tell a trusted adult (96%).12 The ability to say “no” helps individuals protect their own rights, respect the rights of others, behave freely13 and uphold personal values and ideals.14,15 When exercised appropriately in the right place and at the right time, it helps prevent the aggressive behaviours of other individuals.16,17 The current evidence shows that, in general, parental knowledge and attitudes in regard to sexual abuse and what they teach their children are limited and insufficient to protect children from CSA.18,19 In addition, rather than raising children as individuals that accept everything, children need to be raised to be aware of their own bodies20 and taught to say “no” to any kind of request, manipulation or threat from strangers.21 In our review of the literature, we found no study analysing both parental awareness of sexual abuse and the ability of children to say “no”. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess parental awareness of sexual abuse and its association with the ability of children to say “no”.

Materials and methodsStudy designWe conducted a descriptive and correlational study.

ParticipantsThe population of interest consisted of 851 fourth grade students and their parents in a province of north-eastern Turkey, and the study was conducted between April and June 2022. We estimated we needed a sample of at least 269 for a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error.22 The sample included 310 primary school students and their parents (300 mothers and 283 fathers). The study excluded students with disabilities, students whose main caregivers were not the parents (for instance, grandparents) and those who refused to participate.

Tools usedPersonal information formWe developed a personal information form based on the relevant literature.9,23,24 The form consisted of 15 questions about the sociodemographic characteristics of students and parents, such as age, sex, family structure and household income.

The Ability to Say “No” scale for childrenSelf-report scale developed by Yılmaz and Sözer9 to assess the ability of 4th grade students to say “no”. This scale is structured in 2 dimensions, refusal and resistance. Each of these dimensions contains 6 items. The items in the refusal dimension assess whether students can say “no” to demands and behaviours that they dislike or find untrustworthy. In the resistance dimension, there are statements that explore whether students eventually yield due to feelings they may experience after saying “no” or additional manipulation or pressure following their refusal. Students are asked to rate each statement in the items on a 5-point Likert scale as “Never”, “Rarely”, “Sometimes”, “Often” and “Always”. To compute the scores obtained through the scale, items in the refusal dimension are scored normally, while items in the resistance dimension are reverse scored. Each dimension yields a score ranging from 6 to 30. The authors reported a Cronbach α of 0.78 for the refusal dimension and 0.77 for the resistance dimension. In our study, we obtained a Cronbach α of 0.78 for the refusal dimension and 0.87 for the resistance dimension.

The Sexual Abuse Awareness scale for parentsIt was developed by Berkmen and Seçim.23 The scale consists of 23 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (5 “strongly agree”; 4 “agree”; 3 “neither agree nor disagree”; 2 “disagree”; 1 “strongly disagree”). The possible score of the scale ranges from 23 to 115 points. Scores of 57–58 points are average. Increases in the score reflect a greater parental awareness of CSA. The Cronbach α for the scale is 0.90. In our study, the Cronbach α was 0.87 for mothers and 0.88 for fathers.

Ethical considerations and informed consentThe study was conducted in adherence with universal and scientific ethical principles, including the principles of informed consent, autonomy, protection of privacy and confidentiality, equality and do not harm. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by a university ethics committee. We obtained permission to use the scales from their respective authors, the authorization of the Provincial Directorate of National Education, and consent from the parents and children who participated in the study.

Data analysisThe data were analysed with the software package IBM SPSS, version 22. We defined statistical significance as a P value of less than 0.05 or 0.01. We used the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess whether the data followed a normal distribution. In the descriptive analysis, we summarised the data as absolute frequency and percentage distributions and using the mean and standard deviation. We used the Spearman correlation coefficient to assess the association between variables.

Results

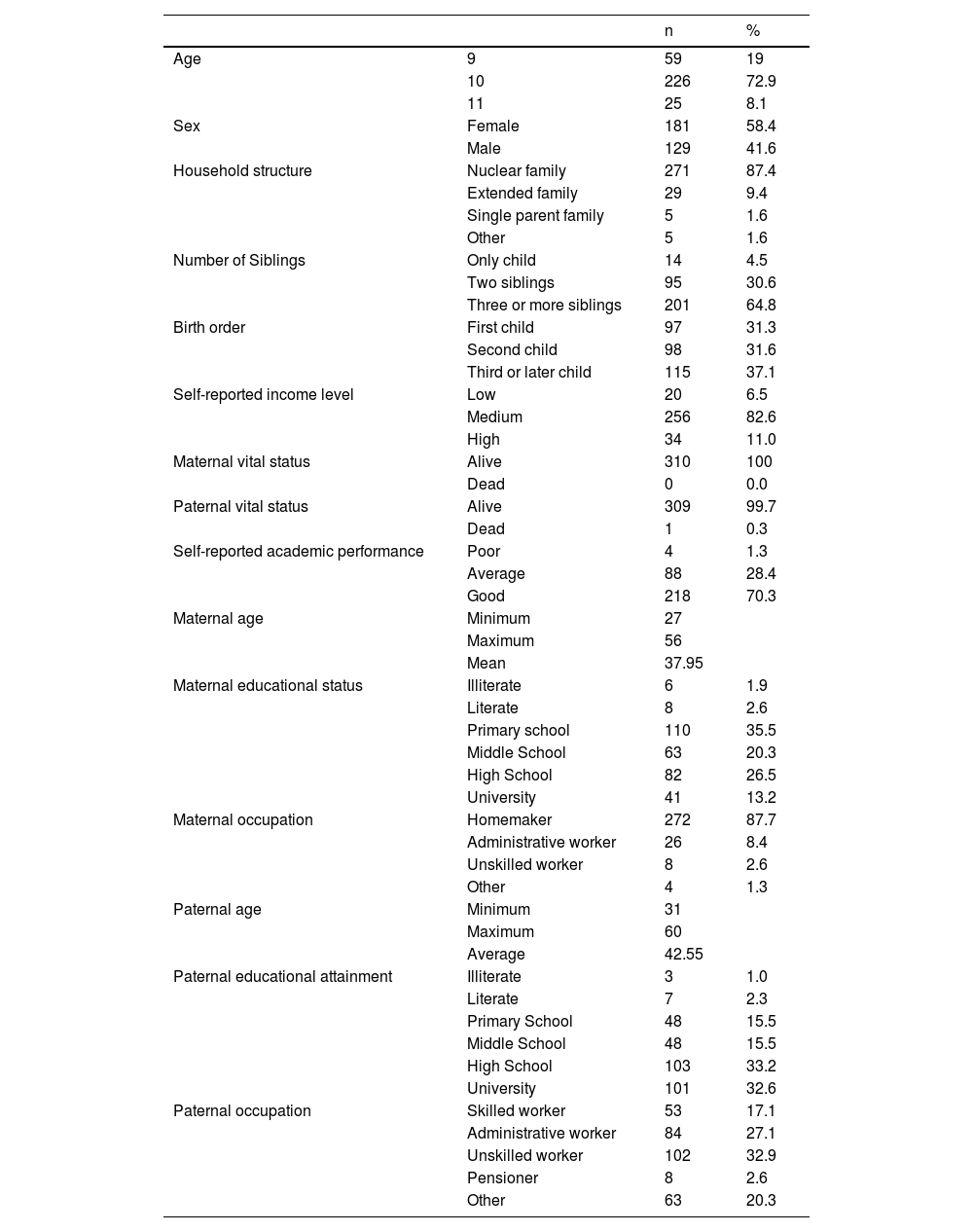

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the children.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants (N=310 children).

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 9 | 59 | 19 |

| 10 | 226 | 72.9 | |

| 11 | 25 | 8.1 | |

| Sex | Female | 181 | 58.4 |

| Male | 129 | 41.6 | |

| Household structure | Nuclear family | 271 | 87.4 |

| Extended family | 29 | 9.4 | |

| Single parent family | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Number of Siblings | Only child | 14 | 4.5 |

| Two siblings | 95 | 30.6 | |

| Three or more siblings | 201 | 64.8 | |

| Birth order | First child | 97 | 31.3 |

| Second child | 98 | 31.6 | |

| Third or later child | 115 | 37.1 | |

| Self-reported income level | Low | 20 | 6.5 |

| Medium | 256 | 82.6 | |

| High | 34 | 11.0 | |

| Maternal vital status | Alive | 310 | 100 |

| Dead | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Paternal vital status | Alive | 309 | 99.7 |

| Dead | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Self-reported academic performance | Poor | 4 | 1.3 |

| Average | 88 | 28.4 | |

| Good | 218 | 70.3 | |

| Maternal age | Minimum | 27 | |

| Maximum | 56 | ||

| Mean | 37.95 | ||

| Maternal educational status | Illiterate | 6 | 1.9 |

| Literate | 8 | 2.6 | |

| Primary school | 110 | 35.5 | |

| Middle School | 63 | 20.3 | |

| High School | 82 | 26.5 | |

| University | 41 | 13.2 | |

| Maternal occupation | Homemaker | 272 | 87.7 |

| Administrative worker | 26 | 8.4 | |

| Unskilled worker | 8 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Paternal age | Minimum | 31 | |

| Maximum | 60 | ||

| Average | 42.55 | ||

| Paternal educational attainment | Illiterate | 3 | 1.0 |

| Literate | 7 | 2.3 | |

| Primary School | 48 | 15.5 | |

| Middle School | 48 | 15.5 | |

| High School | 103 | 33.2 | |

| University | 101 | 32.6 | |

| Paternal occupation | Skilled worker | 53 | 17.1 |

| Administrative worker | 84 | 27.1 | |

| Unskilled worker | 102 | 32.9 | |

| Pensioner | 8 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 63 | 20.3 |

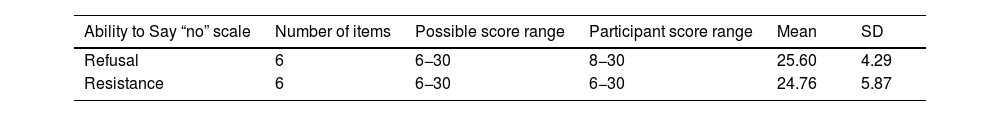

The mean score of the students in the refusal dimension of the Ability to Say “No” scale was 25.60 (SD, 4.29), and the mean score in the resistance dimension was 24.76 (SD, 5.87) (Table 2).

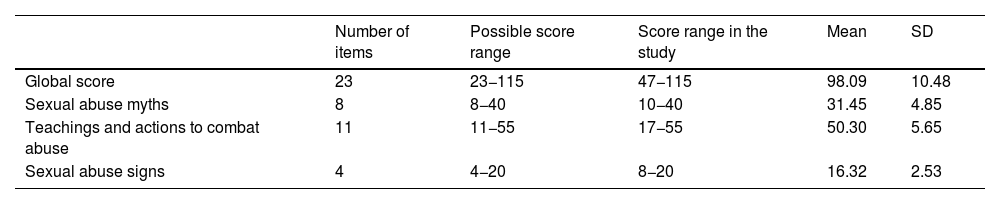

The mean total score of mothers in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale was 98.09 (SD, 10.48). When it came to the dimensions of the scale, the mean maternal score was 31.45 (SD, 4.85) for the “sexual abuse myths” dimension, 50.30 (SD, 5.65) for the “teachings and actions to combat abuse” dimension and 16.32 (SD, 2.53) for the “signs of sexual abuse” dimension (Table 3).

Mean maternal scores in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale (N=300).

| Number of items | Possible score range | Score range in the study | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global score | 23 | 23−115 | 47−115 | 98.09 | 10.48 |

| Sexual abuse myths | 8 | 8−40 | 10−40 | 31.45 | 4.85 |

| Teachings and actions to combat abuse | 11 | 11−55 | 17−55 | 50.30 | 5.65 |

| Sexual abuse signs | 4 | 4−20 | 8−20 | 16.32 | 2.53 |

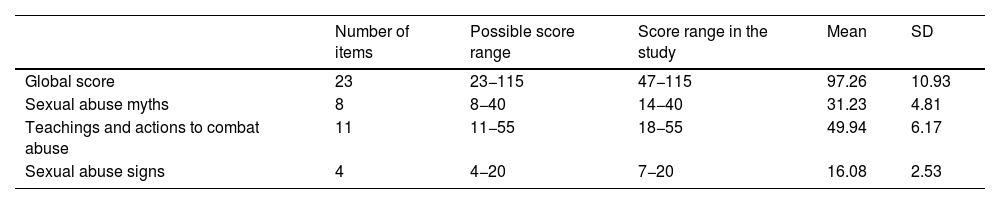

The mean total score of fathers in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale was 97.26 (SD, 10.93). When it came to the dimensions of the scale, the mean paternal score was 31.23 (SD, 4.81) for the “sexual abuse myths” dimension, 49.94 (SD, 6.17) for the “teachings and actions to combat abuse” dimension and 16.08 (SD, 2.53) for the “signs of sexual abuse” dimension (Table 4).

Mean paternal scores in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale (N=283).

| Number of items | Possible score range | Score range in the study | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global score | 23 | 23−115 | 47−115 | 97.26 | 10.93 |

| Sexual abuse myths | 8 | 8−40 | 14−40 | 31.23 | 4.81 |

| Teachings and actions to combat abuse | 11 | 11−55 | 18−55 | 49.94 | 6.17 |

| Sexual abuse signs | 4 | 4−20 | 7−20 | 16.08 | 2.53 |

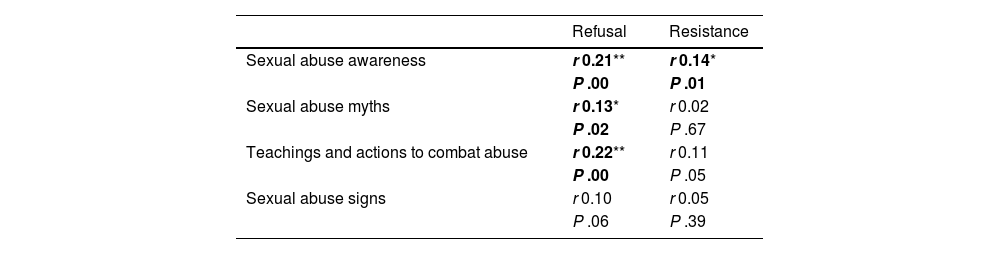

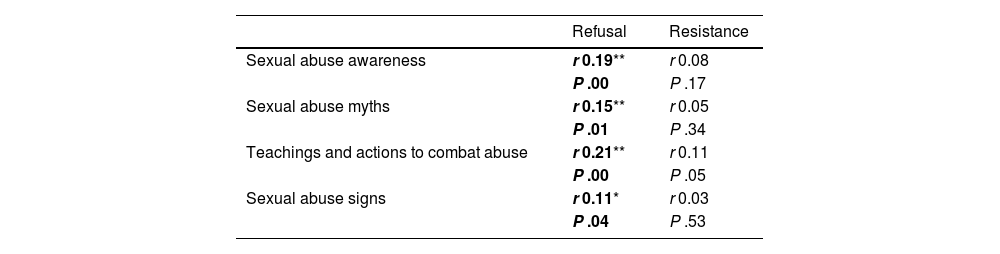

The analysis of the correlation between the mean maternal scores in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale and the mean scores of children in the Ability to Say “No” scale revealed a weak positive correlation (P < .05) between the maternal total sexual abuse awareness scores and the mean refusal and resistance dimension scores of children. There was a weak positive correlation between the mean sexual abuse myths score of the mothers and the mean refusal dimension score of the children (P < .05), and a weak positive correlation between the mean teachings and actions to combat abuse score of the mothers and the mean refusal dimension score of the children (P < .01) (Table 5).

Correlation between the mean maternal scores in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale and the mean scores of children in the Ability to Say “No” scale.

When it came to the correlation between the mean paternal scores in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale and the mean scores of children in the Ability to Say “No” scale; we found a weak positive correlation (P < .05) between the mean paternal sexual abuse awareness score and the mean score of children in the refusal dimension. There was a weak positive correlation between the mean paternal sexual abuse myths score and the mean refusal score of the children (P < .01), a weak positive correlation between the mean teachings and actions to combat abuse score of fathers and the mean refusal score of the children (P < .01) and a weak positive correlation between the mean paternal sexual abuse signs score and the mean refusal score of the children (P < .05) (Table 6).

Correlation between the mean paternal scores in the Sexual Abuse Awareness scale and the mean scores of children in the Ability to Say “No” scale.

In our study, the mean score of children in the refusal dimension of Ability to Say “No” scale was 25.60 (SD, 4.29) and the mean score in the resistance dimension was 24.76 (SD, 5,87) (Table 2). The mean refusal and resistance scores in children were high. It is thought that children’s developing ability to say no may play an important role in protecting themselves from the risk of sexual abuse.

In our study, the mean sexual abuse myths score was 31.45 (SD, 4.85) in mothers (Table 3) and 31.23 (SD, 4.81) in fathers (Table 4). Our study showed that parental awareness of sexual abuse myths was high. This was an encouraging finding. Similar to this study, there are studies in the literature reporting that parents have partial, moderate and good knowledge about sexual abuse.23,25–28 Thapa et al.29 reported that the majority of a sample of 224 mothers (77.8%) had a moderate level of awareness about girl child abuse and only 21 (7.3%) had a good level of awareness about girl child abuse in their study on mothers of girls aged less than 16 years. It is believed that the global scope of the problem of child abuse contributes to parental awareness of sexual abuse.26 Parents may have some false beliefs or distorted cognitions about child abuse. These can lead to unhealthy communication within the family and affect the intrapsychic structure of the child.30

In our study, the mean maternal score on the teachings and actions to combat sexual abuse dimension was 50.30 (SD, 5.65) (Table 3), while the mean paternal score in the same dimension was 49.94 (SD, 6.17) (Table 4). Mothers’ and fathers’ awareness of the teachings and actions to combat sexual abuse was high. Sanberk et al.31 reported in their study with socially advantaged and disadvantaged mothers with 48−66-month-old children that mothers have inaccurate or insufficient knowledge about sexual abuse and how to prevent it. The findings of the study by Sanberk et al.31 differed from those of our study. The authors reported that all of the mothers stated that they did not give information about sexual abuse to their children and that they believed that such education should start in adolescence or primary school because younger children cannot understand this issue at their age.31 Üstündağ32 also reported that parents who did not provide education about sexual abuse to their children were unsure about the age at which such education should be given. A study conducted by Üstündağ32 in parents with children aged 3–6 years found that those who had not taught their children about how to protect themselves from sexual abuse had not provided sexual abuse prevention education because they did not think of discussing sexual abuse, did not have time, thought that their child was too young, thought that the subject might frighten or upset the child, did not know how to explain it, did not have access to sources of information for guidance, did not think they had enough information, felt embarrassed, felt uneasy or thought that sex education was contrary to their culture and beliefs. A systematic review examining the effectiveness of a child sexual abuse prevention programme in India found that parents used various measures to protect their children from the risk of sexual abuse, including educating children about sexual abuse, monitoring and supervising children and creating a safe environment.16 For this reason, it is important for parents to have sufficient knowledge to explain sexual development, sexuality, sexual abuse and to do so in an age-appropriate way.33 In the study conducted in a sample of parents of children aged 3–6 years, Üstündağ32 found that while most parents (70%) provided their children with sexual abuse protection education, they still needed more information and guidance by reliable experts. Alzoubi et al.25 reported that only 17% of mothers started to implement some child sexual abuse prevention measures when their children were very young (1–4 years old) and less than half (48.8%) started when their children were aged 4–6 years. Three quarters of the mothers (74%) stated that educating their children about child sexual abuse could prevent it. It is the responsibility of adults to protect children from sexual abuse. So, it is also important to raise awareness in parents, who are the primary caregivers of children and support their development in every area. Having limited knowledge on the subject, feeling anxious about it or not knowing how to discuss it may prevent parents from talking to their children about sexual abuse and also make it difficult for children to talk to their parents in the case of possible sexual abuse.34 There is evidence supporting that more information and awareness-raising activities are needed to help parents understand that all children are at risk of sexual abuse and that victimisation can occur at any age.32 In our study, the mean score in the sexual abuse signs dimension was 16.32 (SD, 2.53) for mothers (Table 3) and 16.08 (SD, 2.53) for fathers (Table 4). We found a high level of awareness of signs of sexual abuse in parents. In the previous literature, Alzoubi et al.25 evaluated the knowledge and perceptions of mothers about child sexual abuse in Jordan and found that mothers with a higher income or educational attainment and mothers who were employed were more likely to recognise the signs and symptoms of child sexual abuse compared to other mothers. Pullins and Jones35 conducted a study in 150 parents to assess parental knowledge of child sexual abuse symptoms and to identify the factors associated with this knowledge, and reported that parents were aware of child sexual abuse symptoms were in the areas of physical/medical, emotional, sexual behaviour and behaviour towards others. In a study conducted by Thapa et al.,29 mothers of girls aged less than 16 years stated that the most convincing evidence of abuse was the child’s disclosure (74%), the child's behaviour (66%) and the child’s emotions (60%), and cited the denial of the abuser among the factors that increase uncertainty (21%). Plummer36 reported that mothers first learnt about sexual abuse from the verbal reports (42%) or behaviours (15%) of their child victims, that almost half of the mothers felt that something was “not quite right” before learning about the abuse, and that mothers took many actions to clarify what was going on, including talking to their children (66%) or watching events more closely (39%). Bayrak28 reported that parents had awareness of child abuse in a study of parents of children aged 1–6 years; however, the responses were mostly limited to the effects of sexual abuse. Educating mothers about effective ways to explore suspicions of sexual abuse and weigh evidence for or against abuse can increase maternal protection and speed up investigations.36 The fact that there was no association between mothers’ awareness of sexual abuse signs and children’s refusal was an intriguing finding. Considering that mothers tend to be closer to children as the primary caregiver than fathers, this was unexpected.

It has been determined that as the teachings and actions of parents in the fight against sexual abuse increase, the refusal behaviour of children also increases. It is believed that parental beliefs, thoughts and attitudes about sexual abuse are reflected in their behaviour to protect their children from sexual abuse, and this in turn is related to children’s refusal behaviour.

ConclusionIn the study, we found a correlation between mothers’ sexual abuse awareness scores and children’s refusal and resistance scores. There was also a correlation between fathers’ sexual abuse awareness scores and children’s sexual abuse refusal scores. Parents exhibited a high level of awareness of sexual abuse myths. We also found a high parental awareness of the teachings and actions to combat sexual abuse. Parental awareness of the signs of sexual abuse was also high. As the awareness of mothers and fathers about sexual abuse myths increased, the refusal of children also increased. As the teachings and actions of mothers and fathers in combating sexual abuse increased, the refusal of children also increased. Also, as fathers’ awareness of the signs of sexual abuse increased, children’s refusal also increased.

Since the study was conducted on 310 fourth grade students and their parents in primary schools in the central district of a province in north-eastern Turkey between April and June 2022, the research results cannot be generalized to the whole country, which constitutes a limitation of the study. Incidents of sexual abuse tend to remain secret. For this reason, there need to be organizations that can provide support in case of child sexual abuse, access for victims to support pages and internet sites where users can communicate remotely with psychiatrists, psychologists, school paediatric nurses, social workers, support lines against child abuse, internet help centres and guidance regarding the legal process. Information campaigns should be increased through guidance classes at schools and disseminated through mass media, television and social media. These findings can contribute to the development of other studies and strategies to prevent sexual abuse.