Legislation embodies and regulates the common values by which a society is governed. Today’s society is multicultural and dynamic, a consensus must be reached and values consolidated on which different ideological groups can agree, an approach known as the ethics of minima. The concept of the minor has also been changing over the years; from being perceived as passive to being considered an autonomous individual engaged in the development of his or her life project and the bearer of duties and rights to be progressively exercised according to his or her capacity. This approach entails emerging problems. Both aspects need to be regulated in our legislation.

ObjectiveThe objective of this work was to consider the different laws that concern minors from an ethical perspective and from the point of view of the practicing paediatrician.

Material and methodsWe reviewed legislation concerning minors from the 1990s to the present day. For the purpose of discussion, we grouped it into 4 sections: the minor as a patient, protection of the minor, education and new social realities.

ConclusionsCurrent laws reflect a plural society and focus on protecting minority groups. They recognize the minor as the bearer of rights and duties, and consider the acquisition of autonomy to be progressive, guaranteeing equal opportunity and respecting the child’s own pace in achieving his or her potential. Current legislation also stresses the need for a stable environment and states that all forms of violence are preventable. Furthermore, it respects different moral, social and cultural perspectives.

La legislación plasma y regula los valores comunes por los que se rige una sociedad. La actual es pluricultural y cambiante, por lo que es necesario acordar y consolidar unos valores en los que las distintas corrientes estén de acuerdo, conocido como ética de mínimos. La concepción del menor también ha ido cambiando a lo largo de estos años; de una visión pasiva de éste, a ser considerado un sujeto autónomo en desarrollo de su proyecto vital, y portador de deberes y derechos que ejercerá progresivamente en función de su capacidad. Este abordaje conlleva problemas emergentes. Ambos aspectos han de estar regulados en nuestra legislación.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este trabajo es realizar una mirada ética a las diversas leyes en las que se contempla al menor, desde el prisma del pediatra clínico.

Material y métodosSe revisa la legislación que compete al menor desde los años 90 hasta la actualidad. Para su discusión, se agrupa en cuatro apartados: el menor como paciente, la protección del menor, la educación, y las nuevas realidades sociales.

ConclusionesLas actuales leyes reflejan una sociedad plural, y se centran en proteger a los grupos minoritarios. Reconocen al menor como pleno titular de derechos y deberes. Consideran que la adquisición de dicha autonomía es progresiva, con plena igualdad de oportunidades y respeto al ritmo propio para conseguir su potencial. Recalcan la necesidad de un entorno estable. Afirman que toda forma de violencia se puede prevenir. Respetan los diferentes enfoques morales, sociales y culturales.

Today's world is made up of plural societies with different moral systems, different approaches and solutions to the same problem. Through moral judgment, which is shaped by our customs, beliefs and norms, we distinguish what we consider acceptable versus unacceptable and make decisions. But there are no absolutes in this sphere, which is why discrepancies arise between the various systems. In order to avoid conflict, agreements must be reached in handling common problems.

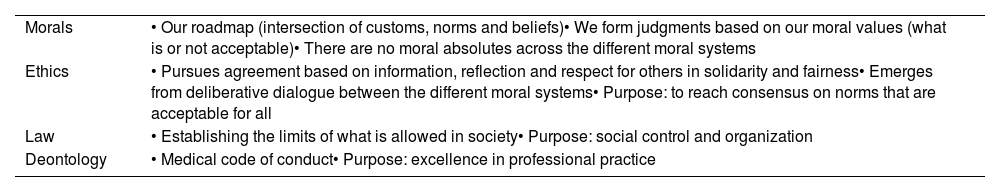

Ethics, deontology and the law1 are essential in the practice of medicine and intimately linked, as the practice of medicine involves decisions that have a profound impact on the life and wellbeing of individuals (Table 1).

Relationship between the different concepts discussed.

| Morals | • Our roadmap (intersection of customs, norms and beliefs)• We form judgments based on our moral values (what is or not acceptable)• There are no moral absolutes across the different moral systems |

| Ethics | • Pursues agreement based on information, reflection and respect for others in solidarity and fairness• Emerges from deliberative dialogue between the different moral systems• Purpose: to reach consensus on norms that are acceptable for all |

| Law | • Establishing the limits of what is allowed in society• Purpose: social control and organization |

| Deontology | • Medical code of conduct• Purpose: excellence in professional practice |

In recent decades, bioethics has emerged as a crucial field, broaching complex issues that arise with technological and scientific advances in medicine and far-reaching social changes, establishing principles and providing a deliberative framework that can guide professionals in making fair and compassionate decisions for the wellbeing of the patient.

Medical ethics and deontology define the duties and responsibilities of physicians, establishing rules of conduct to guarantee professional integrity, competence and responsibility. These rules generate public trust in the health care system and ensure that patients are treated with dignity and respect.

Legislation complements codes of ethics and deontology,2 providing a legal framework that regulates medical practice. Health care laws make the rights and responsibilities of patients and providers explicit and enforceable, ensuring adherence to ethical and deontological standards.

The integration of ethics, deontology and law in medicine promotes a more reflective, fair and humane practice, protecting the rights of all involved parties. The enactment of laws and regulations should reinforce and complement the ethical and deontological framework, guaranteeing that the rights and responsibilities of patients and professionals are clear and enforceable. In this context, bioethics not only seeks answers, but also promotes a more reflective and humane practice of medicine.

Law and bioethics go hand in hand, not to judicialize ethics but rather to identify and establish the minimums of a state, so that the law is the means for establishing the limits of what is allowed, bearing in mind that “the establishment of certain policies entails the choice of a certain model of society that excludes others”, which leads us to consider the kind of society we want to build, the course we want to set for it and the legacy we will pass on to future generations.3

Human rights emerge at the intersection between law and bioethics and constitute the universal minimum standards that must be upheld in decision-making.4 In the case of children, these rights are embodied in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which has yet to be ratified by the United States, a fact that reflects that the country does not recognize a moral obligation to adhere to it.5

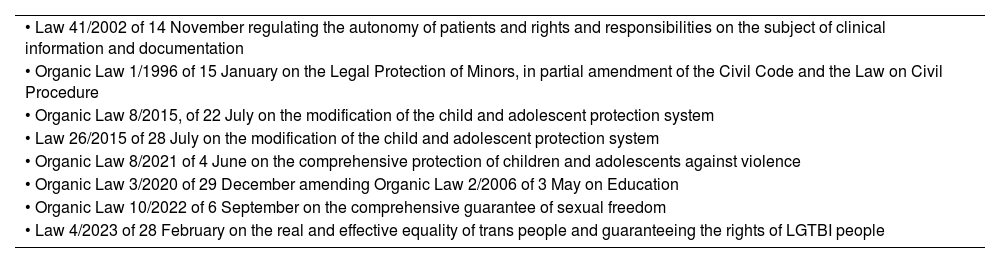

Review of legislation and ethical considerationsWe proceed to a critical review of the laws concerning minors from the 1990s to the present day. To facilitate their understanding, we will group them into four sections according to the subject matter: the minor as a patient, protection of the minor, education and new social realities (Table 2).

Spanish laws concerning minors.

| • Law 41/2002 of 14 November regulating the autonomy of patients and rights and responsibilities on the subject of clinical information and documentation |

| • Organic Law 1/1996 of 15 January on the Legal Protection of Minors, in partial amendment of the Civil Code and the Law on Civil Procedure |

| • Organic Law 8/2015, of 22 July on the modification of the child and adolescent protection system |

| • Law 26/2015 of 28 July on the modification of the child and adolescent protection system |

| • Organic Law 8/2021 of 4 June on the comprehensive protection of children and adolescents against violence |

| • Organic Law 3/2020 of 29 December amending Organic Law 2/2006 of 3 May on Education |

| • Organic Law 10/2022 of 6 September on the comprehensive guarantee of sexual freedom |

| • Law 4/2023 of 28 February on the real and effective equality of trans people and guaranteeing the rights of LGTBI people |

In our analysis of the evolution of Spanish legislation concerning the rights of minors, we highlight the influence of ethical and bioethical principles in its development. In the past few decades, there has been a significant shift in the way society and the legal system perceive and treat minors from a traditional and protective stance to a more modern and participatory perspective that recognises their autonomy and rights.

Our review of the pertinent legislation reveals that, while important progress has been made, challenges and areas of improvement still remain. For example, in the field of health care, while the law allows minors to make informed decisions about their treatment in certain circumstances, there are still restrictions that may limit their autonomy. In education, laws have made progress towards inclusion and equal opportunity, but there are still significant barriers to the practical implementation of these principles.

In terms of child protection, Spanish legislation has reinforced measures against abuse and neglect, but the effectiveness of these laws depends to a large extent on their implementation and the commitment of child welfare institutions. Furthermore, new social realities, such as digital technologies and new family structures, raise ethical and legal challenges that require constant updating and adaptation of regulations.

From a bioethical perspective, it is essential to consider the principle of progressive autonomy, ensuring that the rights of minors are respected at every stage of development. The law must find the balance between protecting minors and respecting their capacity to make decisions, promoting their involvement in matters that concern them.

- 1

The minor as a patient

Law 41/2002

Introduced changesThis law reflected a radical change in the approach to the doctor-patient relationship: from a previous paternalistic model to a patient-centred model, which also applies to minors.6

Ethical perspectiveThe development of autonomy is a gradual process; responsibilities are assumed progressively according to current capacities. Being autonomous means being able to make decisions while understanding their implications. The mature minor doctrine emphasises that it is capacity and not age that determines whether or not a minor can actually make decisions. It falls to the physician in charge of the patient to assess whether the minor is intellectually and emotionally capable of understanding the implications of the decision, which entails a great moral responsibility, and requires specific and continuous training.

In the words of Diego Gracia, “the maturity of a person, whether older or younger, should be measured by their formal capacity to judge and assess situations, not by the content of the values they adopt or apply; historically, the typical error has been to consider anyone who has a value system different from ours as immature or incapable.”7

Minors require consent by proxy, but it is through their participation in decision-making, being listened to and having their views taken into account that they develop autonomy.

Confidentiality is at the core of the respect for autonomy, but in exceptional cases it may be at odds with the best interests of the child. Thus, there are limits that would prevent professional secrecy from being maintained at all costs.8

Traditionally, respect for autonomy has been based on the recognition of the individual. However, this fails to take into account inherent conditions of human beings, such as vulnerability and fragility. We all need care and respect, just as we need to care for and respect others.9 If we advocated for upholding the autonomy of minors by restricting the involvement of the family and close environment in decision-making, we would be doing them a disservice. We need to move from an individual to a relational model of autonomy in which the environment of the minor is taken into account and decision-making is shared.

- 2

The protection of the minor

Organic Law1/1996 of 15 January

Introduced changesThe explanatory statement specifies that the law establishes “a conception of minors as active, participative and creative subjects, with the capacity to modify their own personal and social environment and to participate in the pursuit and fulfilment of their needs and in the fulfilment of the needs of others.”

“Current scientific evidence allows us to conclude that there is no clear-cut difference between protection needs and autonomy-related needs, but rather that the best way to guarantee social and legal protection for children is to promote their autonomy as subjects.”10 We ought to highlight that this law is the first to contemplate social risk in contrast to abandonment or neglect.

Ethical perspectiveFor a minor to become a participatory, creative, active and autonomous subject, he or she must have a family nucleus during childhood that provides for his or her psycho-affective, social and educational needs. If this nucleus is unable, unwilling or incapable of doing so, the child is unprotected and in a situation of maximum vulnerability. It then falls to society, guided by the principles of solidarity and maximum responsibility, to provide the best possible environment, support and guidance for children to be able to fully develop all their faculties, and to do so with maximum transparency.

Such measures should be individualised, striving for fairness and equality, taking into account the specific consequences of each decision and following a process of deliberation by all the professionals involved, with the understanding that such actions should only be applied when family support measures have failed.

Organic Law8/2015 of 22 July and Law 26/2015 of 28 July

Changes introducedThese laws are an extension of one another. Their purpose is to adapt Organic Law 1/1996 to the social changes that had taken place in the last 2 decades and the signing of international agreements by Spain.

They define the concept of the best interest of the minor, which had previously been an indeterminate legal term; consider minors who are dependents “of a woman subject to violence” direct victims of gender violence; establishes a new profile for users of foster care facilities/homes requiring specialised care centres (minors with aggressive behaviour problems, family maladjustment, parent-child violence or severe difficulties in fulfilling parental responsibilities); replace the term deficiencia (deficiency) by discapacidad (disability) and juicio (judgment) by madurez (maturity); recognize that measures involving restrictions of fundamental rights and freedoms should be implemented as a last resort and require previous authorization by the court; include immigrant minors under the custody of the state within the established measures; introduce a chapter on the “responsibilities of the minor”, institute the Central Register of Sex Offenders; make reference for the first time to digital and media literacy, considering it essential for the development of critical thinking and active participation in society of the minor; and contemplate the measures to be taken in the case of prenatal risk (defining this concept) or in the delivery of health care to minors without the consent of the legal guardians.11,12

Ethical perspectiveWe are all fragile and vulnerable, but there are situations and life stages in which this is more pronounced (children at risk, children in care, poverty, disability).13

These aspects are addressed by the ethics of vulnerability and the ethics of responsibility.

In facing individuals that would be considered unfit in terms of natural selection, the sole possible response is the defence and protection of minors in particularly vulnerable conditions. Hans Jonas considers this responsibility a natural and non-reciprocal imperative. For Levinas, it is the face of the other, fragile and vulnerable, that makes me responsible, not the I-self, but alterity: “The responsibility for the other cannot have begun in my commitment, in my decision. The unlimited responsibility in which I find myself comes from the other side of my freedom.”

When it comes to minors with severe behavioural disorders, it is important to consider that:

- 1)

The best treatment comes from early detection and the implementation of preventive measures focused on social welfare, education and employment. Institutionalization should be used as a last resort and requires adequate coordination between the different levels of care and institutions involved.

- 2)

These children and adolescents need to be given the space to develop insight, allowing them to become aware of the mechanisms underlying their behaviour (ranging from a reactive attachment disorder to deeply entrenched identity pathology), work through them and start the process of adjusting to social norms.14

Keeping the child's upbringing and ties within the child's own family and country is a priority. In adoption and foster care, the rights of the child take precedence over the right to a child. Institutionalisation should be an exceptional measure of protection. Respect for the child's family history is equally important, assisting the child in remembering it and maintaining visits to the biological family when deemed necessary.15

Organic Law8/2021 of 4 June

Changes introducedIt is not an amendment of previous laws, and was created at the request of the Comisión Europea to enact the charter of children’s rights and protection at the national level. The United Nations has referred to it as a pioneering law in Europe.16

It underscores that “all forms of violence against children are preventable”, while the previous approach was punitive and focused on responding once the child had already been subject to violence.

It unifies the concept of violence throughout the national territory; considers crucial the specific and continuing education of all professionals who work with children; gives a comprehensive scope to protection, involving every setting where the minor develops (education system, sports, family, private institutions); establishes new roles and/or expands the functions of pre-existing roles; imposes responsibilities in the field of emerging technologies.16

Ethical perspectiveAs José Antonio Marina asserted, “it takes a village to bring up a child.”

A preventive approach to caregiving entails a conception of the other that focuses on what is morally good toward the other and positions the caregiver in the domain of virtue ethics. In the words of Victoria Camps, caregiving/caring “is not only a principle to uphold, but an attitude that should [always] be at play” in human relations.17

MacIntyre proposed a shift in the current paradigm of society, from an emphasis on the autonomy of the individual to the reinforcement of virtues associated with acknowledged dependence. He termed this just generosity. This approach involves attending attentively and affectionately to the needs of others.18

While justice is the virtue driving the will to give each individual what is their due, mercy, or misericordia, goes beyond what is strictly just. Saint Thomas Aquinas considered that this virtue manifested towards those persons, whoever they might be, afflicted by some significant evil, especially if it is not of their own making. It involves the recognition of the other as a neighbour and extends relationships beyond pre-established communities.

EducationOrganic Law3/2020 of December 29

Changes introducedIt expands the groups with special education needs, establishes the competency-based award of the bachillerato (noncompulsory secondary education cycle); introduces education in civic and ethical values and affective-sexual education and eliminates religion from the subjects contributing to the grade point average, Spanish is no longer a compulsory language of instruction, reintroduces artistic education, eliminates end-of-cycle exams and contemplates a new social environment (digitalization, school bullying, sustainable development, environment…).19

Ethical perspectiveFamily and school share responsibility for the ethical and moral education of children.20 While the school is a setting for social cohesion and democratic integration where coexistence, tolerance, respect, justice and responsibility are taught, parents have the role of educators in moral responsibility. The value system shifts from models based on welfare and consumption to models focused on respect, coexistence, tolerance and equality.

It calls for universal, inclusive and equitable education, which entails equal opportunity and respecting the pace of each individual to achieve his or her full potential, avoiding discrimination and understanding learning as a lifelong journey. The acceptance of diversity makes it possible to value the enrichment brought by moral plurality in society and promotes the exchange of different social and cultural approaches.21

New social realitiesOrganic Law10/2022 of September 6

Changes introducedIt regulates new behaviours that were previously not punishable, such as cyberbullying or child grooming, and eliminates the distinction between aggression and abuse; it is commonly known as the “yes is yes” law.22

Ethical perspectiveIn the adolescent, the need for exploration may lead to transgression on more than one occasion.23 The ability to make decisions and to accept the consequences of one's actions requires knowledge and reflection.

Sexual freedom must be linked to co-responsibility. It shifts from the objectification of the other to the pursuit of mutual emotional wellbeing. It positions us in the ethics of respect, where the other is a valid interlocutor. Shared decision-making and co-responsibility arise from verbalisation, communication, consensus and previous negotiation.

Ley 4/2023 of February 28

Changes introducedIt forces all public administrations to implement new administrative procedures for obtaining personal identification documents; it expressly bans the practice of conversion therapy.24

Ethical perspectiveThe individual is above gender, every child is unique and there are no one-size-fits-all solutions.

Identity development is an individual process unique to each person that varies over time and is influenced by the interaction of the cultural, social and family environments. It is important to respect the pace of each person and to listen actively to the narrative of the individual, determining whether it is their own or has been shaped by external factors,25 avoiding rush judgment and stereotyping, and acknowledging the positive nature of diversity.

This requires dealing with uncertainty as a necessary and ongoing aspect of the life of every individual, normalizing it and providing guidance on how to manage it.26

In 2018, the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Pediatrics) developed a position statement on gender diversity that laid out an ethical perspective structured around 7 principles: best interests of the child, protection of the vulnerable population, active listening and support, prudence, responsibility and recognition, and respecting diversity.27

The principle of responsibility calls for avoiding extreme positions, neither trivialising the experience of the child nor rushing to prescribe treatment to assuage the feelings of the child or family, and refraining from simplifying the response to complex and diverse situations when it comes to providing access to medication or surgery.28

At present, pharmacotherapy is based on the use of off-label drugs for which there are no data on their long-term effects. For this reason, any such therapy must be preceded by information on its possibilities and limitations, avoiding unrealistic expectations.

In a universal health care model, the risk of the system becoming unsustainable cannot be underestimated. To avoid this, equity must be pursued along with the balance between social welfare and individual wants and preferences. 29 This requires acting on good will and being aware that we are responsible for managing limited public resources and for the social cost of medical decisions. In other words, finding a balance between justice and nonmaleficence.

Conclusion- none-

Chronologically, there has been a clear shift in the perception of legislation in terms of minimalist ethics. While the laws of the 1990s focused on seeking consensus, current laws reflect a much more pluralistic society and focus on protecting minority groups.

- none-

While past legislation used to focus on the protection of minors, current laws recognize minors as full subjects of law with both rights and duties. Likewise, lawmakers take into account that the development of legal capacity and autonomy to is progressive and promote the active participation of minors in decision making.

- none-

It emphasizes the importance of a stable environment for the development and pursuit of the individual’s life goals.

- none-

It considers all forms of violence preventable. This prevention requires engagement in every setting, involving all the individuals and institutions associated with the child and including emerging frameworks, such as the digital world. This comprehensive approach to child protection and prevention in minors is based on the ethics of responsibility and vulnerability.

- none-

It reflects plurality and diversity. The law aims to respect different moral, social and cultural perspectives, advocating for equal opportunity and respecting the individual's own pace in achieving his or her potential.

- none-

The lack of economic resources in the implementation of these laws means that in many cases their goals are not achieved.