The impact of acute severe hepatitis of unknown origin in children (SHIC) subject to a medical alert in 2022 medical alert is poorly understood.

Materials and methodsObservational study of the incidence, aetiology and clinical presentation of acute hypertransaminasaemia (HTRA) with laboratory values in the severe range (ALT and/or AST ≥ 500 U/L) in paediatric patients (age 0 to 16 years) in one health care zone from 2012 to 2022, comparing the periods of the SHIC alert and the SARS-CoV2 pandemic with previous years.

ResultsThe incidence of severe HTRA of any cause was 195.28 per 100 000 blood tests, with an incidence of 181.38 in the SHIC alert period and 166.09 during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, without statistically significant differences.

Hepatitis of unknown origin accounted for 7.42% of total cases and transaminase levels normalised in 126 days (SD, 99.4). During the SHIC alert period there was a nonsignificant trend towards a higher incidence, as occurred in 2012 and 2018. In this group of cases, there was a significant increase in the presence of fever, vomiting and upper respiratory symptoms and lower levels of albumin and alkaline phosphatase. One patient required a liver transplant.

ConclusionsIn our setting, there was no significant increase in the incidence of severe HTRA of any aetiology or of unknown source during either the SHIC alert or the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. In the SHIC alert period, a clinical pattern emerged characterised by an increase in nonspecific infectious symptoms, so we cannot rule out a higher prevalence of an infectious agent different from the usual involved pathogens, but it did not cause a significant change in epidemiological trends.

La repercusión de los casos de hepatitis aguda grave sin causa filiada (HASCF) de la alerta médica de 2022 en edad pediátrica es muy poco conocida.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional de incidencia, etiología y clínica de hipertransaminasemia (HTRA) aguda analíticamente grave (ALT y/o AST ≥ 500 U/L) en pacientes pediátricos (0 a 16 años) en un sector sanitario del 2012 al 2022, comparando los periodos de la alerta de HASCF o periodo del SARS-CoV2 con los años previos.

ResultadosLa incidencia de HTRA grave por cualquier motivo es 195,28 por cada 100.000 analíticas, mientras que en el periodo de alerta de HASCF fue de 181,38 y durante la pandemia por SARS-CoV2 166,09, sin diferencias estadísticas.

Las hepatitis sin filiar suponen un 7,42% de los casos y normalizaron transaminasas en 126 ± 99,4 días. En el periodo de la alerta de HASCF existe una tendencia no significativa a una mayor incidencia como ocurre en 2012 y 2018. Estos casos presentan significativamente más fiebre, vómitos y síntomas catarrales y cifras más bajas de albúmina y fosfatasa alcalina. Un paciente precisó de trasplante hepático.

ConclusionesEn nuestro medio, ni durante la alerta de HASCF ni durante la pandemia SARS-CoV2, apareció un aumento significativo en la incidencia de HTRA analíticamente grave por cualquier causa en general o sin filiar. En el periodo de alerta de HASCF se objetiva un patrón clínico con más síntomas infecciosos inespecíficos, por lo que no podemos descartar una mayor prevalencia de un agente infeccioso diferente a los habituales, pero sí que éste provocara un cambio en la epidemiología.

On 15 April 2022, the United Kingdom notified the World Health Organisation (WHO) of a health alert following the detection of 10 cases of severe acute hepatitis in children (SHIC) of unknown aetiology1,2 manifesting with severe hypertransaminasaemia with levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 500 IU/L or greater, predominantly in children aged less than 10 years.

In the context of the global outbreak alert, an educational campaign was initiated that targeted both scientists and the general population,3,4 and cases of similar characteristics started to be reported worldwide. During 2022, there were more than 1200 reported cases in the paediatric population, with the highest number recorded in the United States. In Europe, half of reported cases occurred in the United Kingdom.5

In Spain, the Coordination Centre for Health Alerts and Emergencies6 started epidemiological surveillance of the outbreak, with retrospective registration of suspected cases by including those cases with unexplained transaminase elevation above 500 IU/L meeting the criteria for hospital admission starting from January 1, 2022 and prospective registration from the moment the alert was issued (April 2022) to December 28, 2022. During this period, there were 63 notified cases in Spain, all epidemiologically unrelated.7

The most widely accepted hypothesis regarding its aetiology focuses on infection by adenovirus, which was detected concomitantly in a very high proportion of cases in the United Kingdom and a large percentage of cases in the rest of the world.5 However, this hypothesis has remained unproven.8 Some of the alternative hypotheses involve SARS-CoV-2 (a new variant, sequelae from past infection or confinement measures imposed during the pandemic)9,10 adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2)11 or environmental exposure.12,13

Beyond the presence of severe hypertransaminasaemia and associated epidemiological trends, the alert was motivated by the potential risk of liver failure associated with this presentation and attributed to this phenomenon, which was reported in 55 patients worldwide who required or received a liver transplant, 3 of them in Spain, and 29 who died, 2 of them in Spain.5,7

The actual incidence of these cases of acute hepatitis remains unknown, as epidemiological research has focused on severe cases requiring hospital admission and the assessment of changes in incidence in comparison to previous years in transplant centres.9,14 Since it has been hypothesised that the outbreak could be due to an infectious vector, it would be reasonable to expect an increase in cases of acute hepatitis with severe transaminase elevation but that did not require hospital admission.

The aim of our study was to make an objective assessment to determine whether there was a change in the incidence, aetiology or presentation of severe transaminase level elevation during the SHIC alert period,15 especially in cases of unknown aetiology.

Material and methodsWe conducted a comparative study of severe hypertransaminasaemia, defined based on blood transaminase level thresholds,15 comparing the SHIC alert period (January 1–December 28, 2022) and the 10 preceding years (January 1, 2012–December 31, 2021), analysing the clinical and laboratory features of cases of SHIC in both study periods.16

We also compared the same variables in SHIC cases during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Spain (February 1, 2020–December 31, 2022) and in the 8 preceding years (January 1, 2012–January 31, 2020).

We analysed every case of hypertransaminasaemia with severe enzyme elevation (ALT and/or AST ≥ 500 IU/L)15 in paediatric patients (0–16 years) whose tests were performed at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry (pyridoxal phosphate, Beckman AU5800 chemical analyser) of the tertiary care hospital responsible for carrying out all transaminase assays for the 21 basic health zones of the Zaragoza II health sector during the study period, which ranged from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2022.

We calculated the number of new cases, excluding any additional test results in patients with a previous result of severe hypertransaminasaemia in the study period, any patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of hepatitis and, in the group of patients with hepatitis of unknown aetiology, those lost to follow-up prior to normalisation of transaminase levels or in whom the diagnostic workup was still underway.

We also recorded the number of laboratory orders during the study period in which transaminase levels were measured, regardless of the result or age group. We calculated the annual cumulative incidence by dividing the new cases of severe transaminase elevation by the total assays performed in the same period.

In the case of patients with severe hypertransaminasaemia, we reviewed the health records to analyse its aetiology, classifying cases in 8 aetiological groups that combined aspects of the health alert protocol16 and the classification of hypertransaminasaemia causes17: (1) Infectious aetiology: hepatitis A, B or C virus (HAV, HBV, HCV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) or rotavirus, excluding patients with infection by adenovirus or SARS-CoV-2; (2) Decreased cardiac output: sepsis, hypoxia at birth with secondary hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy, interventions with extracorporeal circulation, multiple organ failure; (3) Toxic/drug-induced: chemotherapy, paracetamol, isoniazid, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine and prolonged parenteral nutrition; (4) Mechanical: gallstones, choledochal cysts or malformations, abdominal trauma and liver surgery; (5) Autoimmune: autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease and macrophage activation syndrome; (6) Genetic: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, sickle cell anaemia, Alagille syndrome and cystic fibrosis; (7) Metabolic: glycogen storage disease type IX, Pompe disease, CPT 1 deficiency, long-chain fatty acid beta-oxidation disorders and severe onset of diabetes; (8) Unknown aetiology.

The unknown aetiology group encompassed those patients in whom the aetiological investigation did not identify a cause of hypertransaminasaemia and who remained in follow-up until transaminase levels normalised.15,16

In the statistical analysis, after assessing whether data were or not normally distributed, we used the χ2 test or Fisher exact test and the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test, as applicable, using the statistical package SPSS version 20.0, and defining statistical significance as a P value of less than 0.05.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragon (code CI PI22/469) on November 30, 2022.

ResultsWe identified 189 632 laboratory orders that included measurement of liver enzyme levels in children (aged 0–16 years) requested for any reason during the study period in the laboratory of our tertiary care hospital.

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were a total of 793 cases of severe transaminase elevation during the study period, corresponding to 364 patients.

The mean age of the 364 patients at the time of the first test that detected severe hypertransaminasaemia was 5.44 years (SD, 5.09), with a median of 4 years. With respect to sex, 166 of the patients (45.60%) were female. The care setting from which testing was ordered was inpatient care in 44.18% of cases, hospital-based outpatient care in 20.07%, emergency care in 18.13% and primary care in 17.37%.

When we compared the demographic and laboratory characteristics of patients with severe hypertransaminasaemia in the SHIC alert period versus the preceding years, we did not find statistically significant differences (Table 1).

Comparison of paediatric patients with severe acute hepatitis in the SHIC alert period versus the rest of the years under study (2012–2021).

| Rest (2012–2021) | SHIC alert period | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 5.59 ± 5.12 | 4.23 ± 4.69 | .054 |

| Sex | 45.8% F. 54.2% M | 44% F. 56% M | .816 |

| ALT (U/L) | 834.02 ± 983.96 | 999.22 ± 1206.18 | .163 |

| AST (U/L) | 863.02 ± 1204.5 | 1398.84 ± 2720.77 | .119 |

| New cases of severe HTRA (test results) | 323 | 41 | .699 |

| Test orders including ALT/AST | 167.028 | 22.604 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HTRA, hypertransaminasaemia; SHIC, severe acute hepatitis in children.

In the total sample, the incidence of severe hypertransaminasaemia of any aetiology was 195.28 cases per 100 000 blood test orders that included transaminase level measurement, while in the SHIC alert period it was 181.38 cases per 100 000 tests and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic it was 166.09 cases per 100 000 tests.

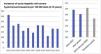

When we compared the different periods, we did find a statistically significant increase in incidence in 2012 compared to all other years, without significant differences between the SHIC alert period or SARS-CoV-2 pandemic period compared to previous years (Fig. 1).

Among the 364 cases of severe transaminase elevation included in the analysis, the aetiology had been identified in 331. Six patients (1.65%) were not included in any aetiological group, 4 because they were lost to follow-up before transaminase levels normalised and 2 because the aetiological investigation was still underway, and 27 (7.42%) had severe acute hepatitis with hypertransaminasaemia whose aetiology could not be determined in the diagnostic evaluation and which resolved spontaneously.

We analysed the distribution by aetiological groups, and found the following frequencies, given in decreasing order: 25% infectious (with EBV as the predominant causative agent followed by HAV), 23.63% low cardiac output (with a relevant proportion of neonates with secondary hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy), 21.15% toxin/drug-related (with most cases due to chemotherapy), 10.99% mechanical, 4.67% autoimmune, 3.57% genetic and 1.92% metabolic.

When we compared the incidence of each aetiological group in the 2 periods under study, we found no significant differences (Fig. 2).

We conducted a more detailed analysis of the unknown aetiology group (27 patients). In every case, follow-up testing evinced spontaneous normalisation of transaminase levels for age and sex at a mean of 126 days (SD, 99.4). The annual incidence was 14.17 cases per 100 000 laboratory orders that included transaminase measurement, compared to 26.54 cases during the SHIC alert period.

In the analysis by year, we found the highest incidence in 2018, with no significant differences. Although there was an increase in incidence during the SHIC alert period, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .098) even when we compared exclusively the period with the highest prevalence worldwide (March–June) to the rest of the years under study. There were also no significant differences in incidence during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic compared to previous years (Fig. 3).

All the cases in the unknown aetiology group occurred in children without comorbidities and who were not currently receiving medication. The mean age in this group was 4.45 years (SD, 4.73), with a median of 3 years, and 75% of the cases in the subset aged less than 10 years.

Coagulopathy was detected in 2 cases. The first corresponded to a patient who met the criteria for liver failure in 2022, with identification of adenovirus in a nasopharyngeal swab sample, and referred to a transplant centre to undergo liver transplantation. The other case of coagulopathy occurred in 2012 in a patient who did not require transplantation and presented with jaundice, choluria and asthenia.

The cases of unknown aetiology in the SHIC alert period did not differ significantly from those in previous years in terms of the age at onset, sex and laboratory values, except for the detection of lower alkaline phosphatase and albumin levels in the SHIC period (Table 2).

Comparison of paediatric patients with severe acute hepatitis of unknown aetiology in the SHIC alert period versus the rest of the years under study (2012-2021).

| Other years (2012-2021) | SHIC alert | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 4.84 ± 5.15 | 3.08 ± 2.73 | .792 |

| Sex | 5 F. 16 M | 2 F. 4 M | .502 |

| ALT (U/L), mean ± SDmedian | 843.52 ± 513.63795 | 2042.83 ± 2695.16581 | .683 |

| AST (U/L), mean ± SDmedian | 723.52 ± 905.83616 | 3187.83 ± 6600.70581 | .770 |

| GGT (U/L) | 96.47 ± 111.59 | 98.25 ± 73.97 | .754 |

| AP (U/L) | 517.41 ± 718.57 | 177 ± 28.58 | .007 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.37 ± 4.86 | 1.16 ± 0.84 | .233 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.18 ± 0.31 | 3.77 ± 0.40 | .029 |

| Fibrinogen (g/l) | 3.37 ± 0.64 | 4.44 ± 1.85 | .108 |

| INR | 1.1 ± 0.24 | 1.37 ± 0.81 | .225 |

| Days to normalization | 122.86 ± 99.48 | 137.83 ± 107.63 | .376 |

| New cases of severe HTRA | 21 | 6 | [1.0].098 |

| Test orders including ALT/AST | 167.028 | 22.604 | |

| Clinical manifestations | |||

| Abdominal pain | 14.3% | 33.3% | .303 |

| Diarrhoea | 14.3% | 33.3% | .303 |

| Vomiting | 4.8% | 50% | .025 |

| Jaundice | 19% | 0 | .341 |

| Cold symptoms | 4.8% | 66.6% | .004 |

| Fever | 14.3% | 83.3% | .004 |

| Weight faltering | 0 | 16.6% | .222 |

| Acute encephalopathy | 0 | 16.6% | .222 |

| Asthenia | 9.5% | 16.6% | .598 |

| Odynophagia | 19% | 16.6% | .341 |

| Petechiae | 4.8% | 16.6% | .778 |

| Asymptomatic | 23.8% | 0 | .252 |

| Liver transplant | 0 | 16.6% | .222 |

| Care setting | PC 5 Hosp 16 | PC 2 Hosp 4 | .502 |

| Hospital admission | 28.6% | 66.6% | .112 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; F, female; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; Hosp, hospital setting; HTRA, hypertransaminasaemia; INR, international normalized ratio (prothrombin time); M, male; PC, primary care centre; SHIC, severe acute hepatitis in children.

Statistically significant differences (P < .05) are presented in boldface.

In terms of the clinical features, there were statistically significant differences, with a greater frequency of vomiting, cold symptoms and fever in the SHIC alert period. In 2022 there was an increase in the frequency of hospital admission that was not statistically significant.

Lastly, we assessed the relative frequency of the additional diagnostic tests ordered by clinicians during the SHIC alert period compared to the previous period and found no significant changes (Fig. 4).

DiscussionThe real impact of the SHIC health alert is difficult to assess. Our study analysed severe transaminase elevation in the paediatric population in an entire health district to have access to a homogeneous record of the years preceding the SHIC alert period or the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic period to be able to analyse their impact as objectively as possible.

Two previous studies14,18 attempted to determine whether there had been an increase in cases of SHIC managed in hospitals during the SHIC health alert by means of surveys, distributed through professional networks or to memberships of scientific societies in Europe. Van Beek et al.18 reported a perceived increase in incidence in some countries, including Spain, while De Kleine et al.,14 whose survey focused more specifically on paediatric liver centres, did not find a clear increase in the incidence of severe acute hepatitis or liver failure.

These studies,14,18 which were conducted quickly following the declaration of the alert due to SHIC and were developed to assess the epidemiological context to determine the severity of the situation, logically carry the risk of the systematic errors associated with the methodology, such as participation, selection or recall bias.

A study conducted in Germany with fewer methodological limitations9 analysed the patients with hepatitis or liver failure managed in the past 30 years in 2 large paediatric hepatology units. This study, in which there was a high percentage of patients with acute liver failure, found an increase in new cases from 2019 that could have been associated with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

One of the drawbacks of previous studies is that they focused on hospitalised patients with severe disease, which means that they had been diagnosed and referred to tertiary care hospitals, probably on account of the clinical severity. There is no doubt that any patient with liver failure will require evaluation at a hospital, but in all likelihood many children with severe hypertransaminasaemia and no evidence of acute liver failure will not be referred to a centre with a transplant programme.15 Given the lack of a confirmed aetiological diagnosis and, more specifically, identification of the causative agent in such cases, it is possible that a substantial proportion of them were not included in these studies.

In our study, we assessed whether there had been an increase in the incidence of severe hypertransaminasaemia in our catchment area regardless of the presence of severe symptoms or associated liver failure.

Needless to say, there are limitations in attempting to estimate the actual incidence of acute hepatitis, as some patients may not have undergone laboratory testing.19 In our case, seeking to obtain as accurate an estimate as possible, we calculated the incidence of newly detected severe hypertransaminasaemia as the number of cases over the total number of tests performed in an entire health district, independently of the care setting where the test was ordered.

Our study did not find significant changes in the incidence of acute hepatitis with severe liver enzyme elevation during the SHIC alert period compared to the 10 previous years. We have also found no differences when we specifically analysed the months with the highest incidence of SHIC globally and nationally7,20 nor during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Considering the entire study sample (2012–2022), we found an increase in cases in one of the previous years (2012). Overall, infection was the predominant aetiology. At the global level, the most frequently involved virus in these cases is HAV, but in the overall sample in our study, the most frequently detected virus was EBV, as is usually the case in countries with better sanitation and vaccination programmes.5,21 The second most frequent aetiology was low cardiac output, and the third one toxin or drug exposure, which are common causes of acute hepatitis in the paediatric age group.17 We did not find statistically significant differences in the aetiological group distribution between the SHIC alert period and the rest of the years under study.

Based on our findings, which reflect real-world clinical practice, the aetiology of severe hypertransaminasaemia could not be determined in fewer than a tenth of the total cases recorded in the entire study period, which resolved spontaneously. We observed an increasing trend in the incidence of cases of unknown aetiology during the SHIC alert period in 2022, but it was not statistically significant and similar increases were also observed in other years, unrelated to the SHIC alert. In this group, specific aetiologies were not necessarily ruled out, as the investigation was not completed in some patients, probably due to the spontaneous normalization of transaminase levels. To assess whether the diagnostic approach was similar during the alert period, we analysed the laboratory orders and found a similar number of orders for each test compared to previous years.

In our case series, the only patient that developed acute liver failure of unknown aetiology, who required referral to a transplant centre for liver transplantation, and who also tested positive for adenovirus, presented in the alert period. Although this clearly is not a statistically relevant finding, based on the data collected by the National Transplant Organization,22 in Spain there was no change in 2022 in the number of paediatric patients who underwent transplantation or entered the waitlist.

In our study, during the SHIC alert period, we found a higher frequency of hypoalbuminaemia, cold symptoms, fever and vomiting in patients with severe hypertransaminasaemia, with no increase in the need of hospital admission. However, there was no increase in cases presenting with coagulopathy, asthenia, abdominal pain or jaundice, which were the clinical features most strongly associated with adenovirus infection,12,23 and which also were not present in patients with SHIC in the Portugal register.4

ConclusionIn conclusion, we did not find evidence of an increase in the incidence of severe transaminase level elevation in Spain during either the SHIC outbreak or the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Although there was an increasing trend in the incidence of severe hypertransaminasaemia of unknown aetiology in the SHIC alert period, the difference was not significant and was also found in the Spanish population in other years included in the analysis.

In our study, we did find a different clinical pattern in cases of hepatitis of unknown aetiology, with a greater frequency of nonspecific infectious symptoms during the SHIC alert period, so we cannot rule out an increased prevalence of an infectious agent other than those usually involved.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.