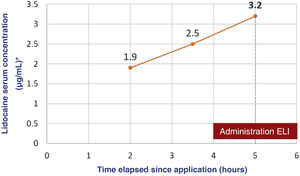

We present the case of a boy aged 5 years with an unremarkable history referred to the emergency department (ED) after developing seizures. The mother reported the application of a full tube of 30g of lidocaine with a concentration of 40mg/g throughout the trunk and extremities followed by occlusive bandaging as indicated preceding the curettage of molluscum contagiosum. An hour later, the patient had an absence seizure with tonic-clonic movements (1min) in the facility where the procedure was to take place. The bandaging was removed and the skin was cleaned quickly. The skin had lesions compatible with eczema, which had been present beforehand. During transport to the ED, the patient had a second seizure and arrived to the department in the postictal phase. A few minutes later, a new episode started, prompting administration of intravenous midazolam, and the patient developed respiratory depression that required manual ventilation. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit breathing spontaneously but still unconscious and with a tendency toward bradycardia. Due to the suspicion of severe lidocaine toxicity, the patient was treated with intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE) at 20% (loading bolus, 1.5mL/kg over 3min followed by boluses of 0.25mg/kg/min over 30min). The skin was decontaminated with abundant water and soap. The patient exhibited gradual improvement and was moved to the ward 24h after his arrival and discharged from hospital on day 3. Serial measurement of serum levels of lidocaine by means of liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry showed a progressive increase that peaked at 3.2μg/mL at 5h post before the administration of ILE (Fig. 1).

The siblings of the patient, on whom lidocaine (40mg/g) had also been applied, were treated at the same time: a boy aged 7 years (application of 2/3 of a tube, approximately 800mg of lidocaine), and another aged 3 years (1/3 of a tube, approximately 400mg). The older one had a tendency toward bradycardia and was admitted and monitored for 24h. The younger one remained asymptomatic and was under observation for 8h.

Lidocaine is an amide local anaesthetic. In paediatric care, it is frequently used as a topical anaesthetic and it is important to remember that high doses or repeated administration can cause systemic toxicity. The latter results from the reversible inhibition of the generation and conduction of action potentials, with both excitatory and depressant effects on the central nervous system and a depressant effect on the cardiovascular system.1 Some of the main neurologic symptoms it can cause are confusion, hallucinations, seizures and coma with apnoea, and some of the cardiovascular symptoms are hypertension and transient tachycardia followed by arrhythmias (sinus bradycardia, junctional or ventricular arrhythmias, asystole). It can cause nausea and vomiting and metahemoglobinemia.1,2 The latter, while possible, is more commonly associated with other local anaesthetics, alone or in combination, such as lidocaine and prilocaine cream.1,2

Table 1 presents the factors that contribute to the development of toxicity, several of which were present in our patient.3 In addition, according to the summary of product characteristics, administration of this drug is not recommended in children aged less than 6 years, so it was prescribed for off-label use.

Cases of severe toxicity in paediatric patients caused by topical lidocaine at doses of 8.6–17.2mg/kg, lower than the doses given to our patients, have been described in the past. The progressive increase in the serum levels of the drug indicated that cutaneous absorption continued during the first hours of management at the hospital and underscores the importance of appropriate and early cutaneous decontamination within the ABCDE approach. As occurred in some previous cases, the peak serum concentration did not exceed the upper limit of the therapeutic range, which suggests that this may not be an adequate reference range for topical administration of lidocaine in children. Another aspect to take into consideration is the variability in the responses to drugs and in the susceptibility to drugs and potential toxicity on account of, for instance, the nearly fifty known polymorphisms of cytochrome CYP450 3A4, which is involved in hepatic drug metabolism.4 As regards the potential toxicity of excipients, the ones involved in the presented case (propylene glycol, benzyl alcohol and soy lecithin) can cause cutaneous or allergic reactions, but do not explain the clinical presentation of the patient.

The management of lidocaine toxicity is based on supportive care.1,2 Intravenous lipid emulsion is one of the most recently introduced antidotes and acts chiefly by reducing the circulating concentration of the drug.5 The evidence supporting its use is strongest for bupivacaine. When it comes to poisoning by lidocaine or other local anaesthetics, the use of ILE is indicated in the case of life-threatening toxicity that does not respond to supportive care.6

Last of all, efforts must be made to prevent this type of poisonings. Families must be informed of the risk of systemic toxicity associated with the incorrect use of these drugs, be given the dosage in writing and warned never to exceed the maximum recommended dose.