Pain management and sedation is a priority in neonatal intensive care units. A study was designed with the aim of determining current clinical practice as regards sedation and analgesia in neonatal intensive care units in Spain, as well as to identify factors associated with the use of sedative and analgesic drugs.

MethodA multicenter, observational, longitudinal and prospective study.

ResultsThirty neonatal units participated and included 468 neonates. Of these, 198 (42.3%) received sedatives or analgesics. A total of 19 different drugs were used during the study period, and the most used was fentanyl. Only fentanyl, midazolam, morphine and paracetamol were used in at least 20% of the neonates who received sedatives and/or analgesics. In infusions, 14 different drug prescriptions were used, with the most frequent being fentanyl and the combination of fentanyl and midazolam.

The variables associated with receiving sedation and/or analgesia were, to have required invasive ventilation (p<.001; OR=23.79), a CRIB score >3 (p=.023; OR=2.26), the existence of pain evaluation guidelines in the unit (p<.001; OR=3.82), and a pain leader (p=.034; OR=2.35).

ConclusionsAlmost half of the neonates admitted to intensive care units receive sedatives or analgesics.

There is significant variation between Spanish neonatal units as regards sedation and analgesia prescribing. Our results provide evidence on the “state of the art”, and could serve as the basis of preparing clinical practice guidelines at a national level.

El manejo del dolor y la sedación es una prioridad de los cuidados intensivos neonatales. Se diseñó un estudio con el objetivo de determinar la práctica clínica actual en relación con la sedación y la analgesia en unidades de cuidados intensivos neonatales en España e identificar factores asociados al uso de fármacos sedantes o analgésicos.

MétodoEstudio multicéntrico, observacional, longitudinal y prospectivo.

ResultadosParticiparon 30 unidades neonatales y se reclutó a 468 neonatos. De estos, 198 (42.3%) recibieron medicación sedante o analgésica. En total, se usaron durante el período de estudio 19 fármacos distintos, de los cuales el más utilizado fue el fentanilo. Solo fentanilo, midazolam, morfina y paracetamol se usaron al menos en un 20% de los neonatos que recibieron sedación y/o analgesia. Se usaron 14 pautas distintas de fármacos en perfusión, siendo las más frecuentes la infusión de fentanilo y la combinación de fentanilo y midazolam.

Las variables asociadas a recibir sedación y/o analgesia fueron el haber precisado ventilación invasiva (p=<0.001; OR=23.79), un score de CRIB>3 (p=0.023; OR=2.26), la existencia en la unidad de guías de evaluación del dolor (p<0.001; OR=3.82) y de un líder de dolor (p=0.034; OR=2.35).

ConclusionesCasi la mitad de los neonatos ingresados en cuidados intensivos recibe medicación sedante y/o analgésica.

Existe una importante variabilidad entre las unidades neonatales españolas en relación con las pautas de sedación y analgesia. Nuestros resultados permiten conocer el “estado del arte” y pueden servir de base para la elaboración de guías de práctica clínica a nivel nacional.

Pain relief is a basic human right at any age. In new-borns, the inherent difficulty in detecting pain and the false belief that neonates lack the necessary physiological pathways for pain transmission have led to the historical undertreatment of this age group.1 Nowadays, it is known that new-borns admitted to intensive care units (ICU) undergo multiple painful procedures during their stay.2,3 Besides, there is enough evidence suggesting that untreated pain during the neonatal period can have short-term and long-term negative consequences.4–8

Currently, there is a wide range of resources for the management of sedation and/or analgesia (S/A), including pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures, but, in practice, many guidelines are based on experts’ consensus, local protocols or even personal preferences. In an attempt to determine common clinical practices regarding pain management in neonatal units, surveys have been published in different countries in recent years: France,9 Canada,10 United Kingdom,11,12 Australia,13,14 Italy,15 United States,16 Germany, Austria and Switzerland,17,18 and Sweden.19 As far as it is known, in Spain there is currently no data about the management of S/A in new-borns that allows for critical analysis, or that represents a first step towards the preparation of clinical practice guidelines.

Within the framework of the international multicentre project Europain (www.europainsurvey.eu), a specific study for the Spanish sample was designed to determine the current and actual clinical practices regarding the use of sedative and analgesic drugs in neonatal ICUs in Spain and the factors associated with their use.

Material and methods- –

Design: Europain-Spain is an observational, longitudinal and prospective study.

- –

Selection of units: a list of the neonatal ICUs of the public health care network in Spain was obtained from the Spanish Society of Neonatology in 2012. Thirty-four units were invited to participate via e-mail. These provided comprehensive intensive health care services, including all forms of invasive mechanical ventilation. Two units rejected the invitation, one unit failed to respond and another unit withdrew from the study upon commencement. Finally, 30 neonatal units from all over the country participated (Appendix 1).

- –

Inclusion criteria: each of the participating units included all new-borns that were admitted during a given month (November 2012) until a corrected age of 44 weeks, and whose legal guardian(s) had signed the informed consent form to participate in the study.

- –

Data collection: the following information was obtained for each neonate: demographical data; data about respiratory assistance devices; use of sedatives, analgesics or muscle relaxants; and drug abstinence management. Data collection for each included new-born lasted 28 days or until their discharge, transfer to another hospital, or death. Furthermore, unit coordinators provided data about local protocols on S/A and general unit statistics. A self-audit was conducted in each participating hospital for quality control purposes by a person other than the one responsible for the data entry.

- –

Ethical aspects: approval was obtained from the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Healthcare Products and from the referent clinical investigation ethics committee, as well as from local committees, as required. The informed consent was obtained from the parents and/or legal guardians of all the included neonates.

- –

Data analysis: a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the participating units and the included patients and their management was conducted, and interval estimates were reported on the main findings. Variables associated with the use of S/A were analysed using the square chi test or the Fisher's exact test and the Mann–Whitney's test, and odds ratio values and their 95% confidence interval were calculated. A multivariate logistic regression model was adjusted to determine the associated variables independently of the use of S/A. Given that each unit included a variable number of neonates, the adjustment was based on generalised estimating equation models.20,21 This approach includes the dependency that may exist between data from neonates admitted to the same unit and makes it possible to avoid bias associated with classic techniques when the independence hypothesis cannot be sustained. A forward modelling strategy was implemented, and variables with a value of p<0.20 in the bivariate analysis were included in the model. For the multivariate analysis, units were classified based on the number of annual admissions (above or below 250) and the number of annual surgical admissions (above or below 25). Patients were also classified based on a clinical risk index for babies (CRIB) score above 3 and equal to or below 3. The statistical analysis was carried out using the software SPSS 19.0 for Windows. All tests were conducted based on a bilateral approach. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

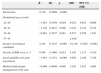

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the 30 participating units. In total, 468 neonates were included. Their general characteristics are shown in Table 2. Of the total, 202 neonates (43.2%; 95% CI, 38.5–47.7) received invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) during a mean time±SD of 126.9±173.5h.

Characteristics of participating units (n=30).

| Unitsn=30 | |

|---|---|

| Existence of local guidelines for pain treatment in 2012, n (%) | 20 (66.6) |

| Existence of local guidelines for pain assessment in 2012, n (%) | 13 (43.3) |

| Number of beds | |

| Mean±SD | 13.1±7.0 |

| Median (range) | 12 (2–33) |

| Number of admissions/year | |

| Mean±SD | 272.9±137.1 |

| Median (range) | 251 (50–624) |

| Number of surgical admissions/year | |

| Mean±SD | 42.9±54.1 |

| Median (range) | 25 (0–222) |

| Number of attending physicians | |

| Mean±SD | 4.9±3.4 |

| Median (range) | 4 (2–15) |

| Existence of a medical chief of pain management, n (%) | 6 (20) |

| Existence of a nurse chief of pain management, n (%) | 4 (13.3) |

| Existence of a pain management team in the unit, n (%) | 13 (43.3) |

| 24-hour visiting for parents, n (%) | 26 (86.6) |

SD: standard deviation.

Characteristics of neonates included in the study of the total sample and based on the maximum respiratory assistance received during the study period.

| Variable | Total n=468 | Invasive mechanical ventilation n=202 (43.2%) | Non-invasive ventilation n=149 (31.8%) | Spontaneous respiration n=117 (25%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 34.3±4.6 | 33.4±5.2 | 33.5±4 | 36.9±3.5 | <0.001 |

| Mean (IQ) | 34.3 (30.2–38.5) | 33.9 (29.1–38) | 33.1 (30.2–35.3) | 37.4 (33.9–39.8) | – |

| 24–29, n (%) | 107 (22.8) | 70 (34.7) | 34 (22.8) | 3 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| 30–32, n (%) | 76 (16.2) | 24 (11.9) | 37 (24.8) | 15 (12.8) | |

| 33–36, n (%) | 115 (24.5) | 38 (18.8) | 45 (30.2) | 32 (27.4) | |

| 37–42, n (%) | 170 (36.3) | 70 (34.7) | 33 (22.1) | 67 (57.3) | |

| Birth weight (g) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 2.182,8±9764 | 2.051±1007 | 1.985±8499 | 2.663±9197 | <0.001 |

| Mean (IQ) | 2.081 (1390–3025) | 2.050 (1.089–2905) | 1.880 (1.350–2,425) | 2.720 (1,805–3,310) | – |

| Male, n (%) | 256 (54.7) | 113 (55.9) | 75 (50.3) | 68 (58.1) | 0.228 |

| Born in hospital, n (%) | 377 (80.5) | 143 (70.8) | 138 (92.6) | 96 (82.1) | <0.001 |

| Age at admission (h) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 64.9±237.3 | 85.5±309.2 | 32.7±152.3 | 70.7±171.4 | 0.114 |

| Mean (IQ) | 0.5 (0.23–6.1) | 0.5 (0.3–7.3) | 0.3 (0.2–1) | 0.5 (0.2–48.3) | – |

| CRIB score | |||||

| Mean±SD | 2.1±3.0 | 4±3.7 | 1±1.4 | 0.6±1.0 | <0.001 |

| Mean (IQ) | 1 (0.0–3.0) | 3 (1–6) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | – |

| Apgar score at 5min (n=467) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 8.3±1.8 | 7.6±2.2 | 8.8± 1.1 | 9.2±1.1 | <0.001 |

| Mean (IQ) | 9 (8–10) | 8 (6–9) | 9 (8–10) | 9 (9–10) | – |

| Already intubated on admission, n (%) | 112 (23.9) | 112 (55.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| Death during the study period, n (%) | 21 (3.2) | 21 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalisation (days)a | |||||

| Mean±SD | 15.3±10.0 | 17.0±10.1 | 16.9±9.8 | 10.5±8.6 | <0.001 |

| Mean (IQ) | 14 (6–28) | 18 (7–28) | 17 (8–28) | 7 (4–14.5) | <0.001 |

The CRIB is an index used for the measurement of severity validated in preterm neonates composed of 6 items collected during the first 12h of life. The score ranges from 0 to 23, where higher values indicate higher severity.

SD: standard deviation; IQ: interquartile range; NA: not applicable.

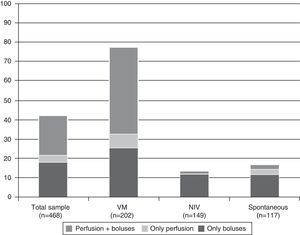

On a global scale, 198 neonates (42.3%; 95% CI, 37.7–46.8) received some kind of sedative or analgesic medication. Of these, 16 (8%) received it only in perfusion, 85 (42.9%) only in boluses, and 97 (48.9%) in perfusion and boluses.

Of the 202 neonates who received invasive MV, 158 (78.2%; 95% CI, 72.2–84.1) received some kind of sedative or analgesic medication. Fig. 1 shows the percentage of neonates who received some kind of sedative or analgesic medication and its route of administration, based on the maximum respiratory assistance received during the study period.

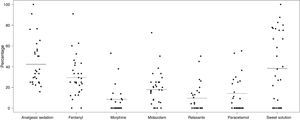

The most commonly used drug was fentanyl, both in perfusion and in boluses, which was used in 138/468 neonates (29.4%). Table 3 shows the use of most common drugs and their route of administration (perfusion or boluses). In total, 19 different drugs were used during the study period. Only fentanyl, midazolam, morphine and paracetamol were used, at least, on 20% of neonates who received S/A. Fig. 2 shows the percentage of patients who received each drug in each participating unit and graphically presents the variability between centres regarding the use of these drugs.

Percentage of patients treated with different sedative or analgesic drugs during the study period and route of administration. The table shows the percentages of the total of patients (n=468) who received each drug.

| Total (n=468) | Route of administration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| In boluses | In perfusion | ||

| Fentanyl, n (%) | 138 (29.4) | 111 (23.7) | 97 (20.7) |

| Midazolam, n (%) | 84 (17.9) | 75 (16.0) | 40 (8.5) |

| Paracetamol, n (%) | 66 (14.1) | 66 (14.1) | – |

| Morphine, n (%) | 40 (8.5) | 30 (6.4) | 23 (4.9) |

| Metamizole, n (%) | 16 (3.4) | 15 (3.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Fenobarbital, n (%) | 12 (2.5) | 12 (2.5) | – |

| Clonidine, n (%) | 12 (2.5) | 8 (1.7) | 4 (0.8) |

| Propofol, n (%) | 10 (2.1) | 10 (2.1) | – |

| Ketamine, n (%) | 6 (1.2) | 6 (1.2) | – |

| Remifentanyl, n (%) | 5 (1.0) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) |

| Meperidine, n (%) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) | – |

| Diazepam, n (%) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) | – |

| Penthotal, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | – |

| Phenytoin, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | – |

| Bupivacaine, n (%) | 2 (0.4)a | – | 2 (0.4) |

| Lorazepam, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | – |

| Chloral hydrate, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | – |

| Levomepromazine, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | – |

| Sevoflurane, n (%) | 1 (0.2)b | 1 (0.2) | – |

Graphical representation of the use of the most common drugs in each of the 30 participating units. The horizontal line indicates the percentage of each variable in relation to the total sample. The dots represent the percentage of patients who received each drug in each of the participating units.

For the 113 neonates who received sedative or analgesic drugs in continuous perfusion, 14 different guidelines were implemented, the most common one being fentanyl infusion (46 neonates, 40.7%) and the combination of fentanyl and midazolam (26 neonates, 23%).

Of the 202 neonates who received invasive MV, 45 (22.2%; 95% CI, 16.2–28.2) received some kind of muscle relaxant. Ten neonates received it via continuous perfusion (9 vecuronium, 1 cisatracurium) and 41 in boluses (33 vecuronium, 7 succinylcholine, 1 cisatracurium).

A total of 180 neonates (38.4%; 95% CI, 33.9–42.9) received some kind of oral sweet solution, the most common one being sucrose (174 neonates), followed by glucose (6 neonates).

Abstinence syndrome was diagnosed in 25 of the 165 neonates who had received opioid or benzodiazepine (15.2%). In 33 neonates, a clinical scale was used for abstinence assessment, the most common being the Finnegan scale (27 neonates, 81.8%), followed by the Lipstiz scale (5 neonates, 15.1%). A total of 28 neonates received medication for the specific treatment or prevention of abstinence symptoms. The most commonly used medication was morphine (14 neonates, 50%), followed by clonidine (9 neonates, 32.1%) and methadone (8 neonates, 28.5%).

Factors associated with sedation and/or analgesiaFinally, variables related to neonates or to units associated with the use of S/A were analysed (Table 4). Based on the multivariate analysis, the associated variables were the following: having received invasive MV (p<0.001; OR=23.79); a CRIB score>3 (p=0.023; OR=2.26); the existence of local guidelines for pain assessment in the unit (p<0.001; OR=3.82); and the existence of a medical chief of pain management in the unit (p=0.034; OR=2.35). However, a gestational age below 33 weeks was significantly associated with a lower chance of receiving S/A. The use of pain assessment tools and the size of the unit (according to the number of annual admissions or surgical admissions) were not associated with the use of S/A (Table 5).

Variables associated with the use of sedative or analgesic medication. Univariate analysis.

| Use of sedative/analgesic medication | p | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yesn (%) | Non (%) | |||

| Gestational age | 0.004 | |||

| 24–29 weeks | 51 (47.6) | 56 (52.4) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | |

| 30–32 weeks | 23 (30.2) | 53 (69.8) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | |

| 33–36 weeks | 39 (33.9) | 76 (66.1) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | |

| 37–42 weeks | 85 (50.0) | 85 (50.0) | 1 | |

| Prematurity (≤36 weeks | 0.011 | |||

| Yes | 113 (37.9) | 185 (62.1) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | |

| No | 85 (50.0) | 85 (50.0) | 1 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 158 (78.2) | 44 (21.8) | 20.2 (12.6–32.5) | |

| No | 40 (15.0) | 226 (85.0) | 1 | |

| Use of pain assessment tools | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 46 (58.9) | 32 (41.1) | 2.2 (1.3–3.6) | |

| No | 152 (38.9) | 238 (61.1) | 1 | |

| Local guidelines for pain treatment | 0.553 | |||

| Yes | 140 (43.2) | 184 (56.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | |

| No | 58 (40.2) | 86 (59.8) | 1 | |

| Local guidelines for pain assessment | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 113 (58.5) | 80 (41.5) | 3.1 (2.1–4.6) | |

| No | 85 (30.0) | 190 (70.0) | 1 | |

| Medical chief of pain management in the unit | 0.088 | |||

| Yes | 43 (50.5) | 42 (49.5) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | |

| No | 155 (40.4) | 228 (59.6) | 1 | |

| Nurse chief of pain management in the unit | 0.291 | |||

| Yes | 26 (49.0) | 27 (51.0) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | |

| No | 172 (41.4) | 243 (58.6) | 1 | |

| Pain management team in the unit | 0.524 | |||

| Yes | 95 (40.2) | 141 (59.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | |

| No | 98 (43.1) | 129 (56.9) | 1 | |

| 24-h visiting for parents | 0.268 | |||

| Yes | 184 (43.0) | 243 (57.0) | 1.6 (0.7–3.3) | |

| No | 14 (34.1) | 27 (65.9) | 1 | |

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | p | OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity (CRIB score) | 3.7±3.6 | 1.0±1.8 | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) |

| Number of beds in the unit | 16.1±7.5 | 14.3±7.0 | 0.008 | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) |

| Number of annual admissions | 329.9±138.3 | 296.4±130.7 | 0.008 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) |

| Number of annual surgical admissions | 70.9±66.7 | 53.6±57.5 | 0.003 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) |

The CRIB is an index used for the measurement of severity validated in preterm neonates composed of 6 items collected during the first 12h of life. The score ranges from 0 to 23, where higher values indicate higher severity.

SD: standard deviation; OR: odds ratio.

Logistic regression multivariate model using generalised estimating equations of factors associated with the use of sedation or analgesia in neonates.

| B | SE | p | ORa | 95% CI (OR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intersection | 4.138 | 0.5806 | <0.001 | |||

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||||||

| 24–29 | −1.563 | 0.5439 | 0.004 | 0.210 | 0.072 | 0.609 |

| 30–32 | −1.126 | 0.4221 | 0.008 | 0.324 | 0.142 | 0.742 |

| 33–36 | −0.663 | 0.3537 | 0.061 | 0.515 | 0.258 | 1.031 |

| 37–42 | 1 (ref) | |||||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 3.183 | 0.3147 | <0.001 | 24.116 | 13.016 | 44.682 |

| Severity (CRIB score)>3 | 0.786 | 0.3466 | 0.023 | 2.195 | 1.113 | 4.330 |

| Local guidelines for pain assessment | −1.401 | 0.3151 | <0.001 | 4.058 | 2.189 | 7.526 |

| Medical chief of pain management in the unit | −0.809 | 0.4049 | 0.046 | 2.245 | 1.015 | 4.965 |

The CRIB is an index used for the measurement of severity validated in preterm neonates composed of 6 items collected during the first 12h of life. The score ranges from 0 to 23, where higher values indicate higher severity.

B: regression coefficient; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

As far as it is known, the study is the first prospective, multicentre study for the management of S/A in a sample of neonates admitted to Spanish neonatal units. In this study, 42.3% of neonates received some kind of sedative or analgesic medication, which reached 78.2% in patients who received invasive MV. Of the total neonates, 31.8% received opioids and 17.9% received midazolam. The most commonly used opioid was fentanyl, which was administered to 29.4% of the total neonates.

Almost half of the neonates received some kind of sedative or analgesic drug in this study. On an international scale, in 2003, 60.3% of a sample of 151 Dutch neonates received some kind of pharmacological analgesia,3 but this percentage was significantly reduced to 36.6% in the same units 8 years after the intensification of non-pharmacological measures, the implementation of health care measures from the New-born Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) and the development of a treatment protocol based on the clinical assessment of pain.22 In the group of neonates with invasive MV, the percentage of S/A amounted to 78.2%. The most commonly used drug was fentanyl, followed by midazolam, paracetamol and morphine, which presented similarities with the findings obtained in a previous Italian survey.15 MV is a stressful and potentially painful technique. Besides, the failure to adapt to or the “struggle” with the respirator may prevent adequate ventilation and have a harmful effect.23 International recommendations have been published to promote the use of opioids in ventilated neonates7 and their use has been assessed in 2 studies of good methodological quality24,25 and in one meta-analysis.26 Results ought to be carefully assessed. It has been observed that morphine has a slight effect on pain assessment scales during painful procedures, whereas it has no effect on the prevention of neurological damage or death.24,25 Besides, the use of morphine has been associated with more time to achieve full enteral nutrition in premature neonates. However, it should be emphasised that synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, have not been assessed in those aspects and that, particularly, the use of analgesics to relieve neonates’ pain and suffering is, in itself, a sufficient reason for their use, even if there is no effect whatsoever on clinical results.

In Spain, there are several opioids available, but in neonatal units their use is generally limited to fentanyl and morphine, and no other opioids can be recommended at the moment. The increased use of fentanyl in Spanish units may be explained by the fact that this drug may have some theoretical advantages (strong, rapid action, short duration) with an analgesic effect similar to morphine,27 although there are very few randomised studies on this, all of which have a small number of patients.28,29

In relation to drugs with mainly sedative action, benzodiazepines are the most commonly used drugs. Midazolam is very commonly used (42.4% of neonates who received some kind of S/A), in spite of the absence of proven benefits, the concern for its influence on neurodevelopment, in both animals30 and humans,6 and of recent revisions advising against its routine use.31

As in other previous studies, our results indicate a great variability in the S/A guidelines among the 30 participating units.2 The 19 different drugs used, the 14 different combinations of drugs in perfusion and the dispersion of percentages indicating the use of the different drugs expressed in Fig. 2 show the lack of common consensus guidelines among Spanish units. This great variability was detected due to bedside data collection of the patient. Most probably, the use of these medications may not be detected in survey-like studies. Similarly, Jenkins et al., in a prospective study involving 338 paediatric patients (including 39 neonates) from 20 units in the United Kingdom, reported the use of 24 different sedative or analgesic drugs.32 Thus, these differences among units hinder the comparison of results and the analysis of S/A in our country.

Oral sweet solutionsThe use of oral sweet solutions during potentially painful procedures has been widely recommended.33,34 Nevertheless, in our study, only 38.4% of neonates received some kind of oral sweet solution (sucrose or glucose). It is possible that registration of administration of oral sweet solutions is more lax than that of drugs, although the prospective nature of the study should have minimised this potential error. Besides, it is possible that there is still a reluctance towards their use because their specific action mechanism is still unknown. Twelve units used sweet solutions on more than half of their patients, while in 9 units these solutions were not used on any of the patients included in the study. This variability, although also observed with other drugs, is particularly notable in the case of oral sweet solutions.

Local guidelines for pain treatment and pain assessmentDespite international recommendations regarding the advisability of establishing pain management protocols,35 one third of the units declared that they had no written protocol, which is similar to what occurred in the study conducted by Mencía et al. in 36 paediatric ICUs in Spain in 2011, in which 64% of the units stated that they had a written protocol for sedoanalgesia.36 At an international level, the percentage of neonatal units with written protocols ranges from 15%13 to 88%.19 The percentage of our sample is similar to that obtained in other related countries.9,11,14,15,17

Factors associated with sedation and/or analgesiaThe multivariate analysis showed that variables associated with an increased use of S/A were term age, MV, severity on admission based on the CRIB score, the existence of local guidelines for pain assessment and the existence of a medical chief of pain management. MV was the factor most commonly associated with the use of S/A.

Previous studies have shown pain management differences associated with the size of the units,17,19 the assistance level11,12 and the surgical nature.11 In our sample, the number of annual admissions (above or below 250) and the number of annual surgical admissions (above or below 25) were not associated with the use of S/A. There is very little information about the influence of local guidelines for pain management in neonatal units. Some previous studies show significant differences among units with written protocols and units without them.17,37 In our sample, only the existence of local guidelines for pain assessment was independently related to an increased use of S/A, although the implementation of pain assessment tools itself was not significantly associated.

LimitationsThe generalisability of results, which is particularly important in this case, is a very common concern. Most of the invited neonatal units participated in our study. These included units from all over the country and a high number of consecutive, non-selected patients. Thus, we believe that they faithfully represent the actual situation of S/A in Spain. It cannot be ruled out that study participation, as it implies awareness of being observed, modifies practices (Hawthorne effect). An attempt to minimise this effect was a relatively lengthy inclusion period (one month) and follow-up period (28 days), which ensured personnel rotation.

Although the initial development of the CRIB scale was conducted in neonates of less than 32 weeks,38 it was chosen in this study for severity measurement mainly due to its simplicity and widespread use,39 but also because prematurity was the main diagnosis on admission and because of its previous use in similar studies.2

The doses of used drugs and the non-pharmacological measures implemented for pain management were not assessed. The non-collection of this information was aimed at facilitating data collection and at making the study viable. In this sense, the decision was successful, but limits the possibility of analysing aspects of undoubted interest.

ConclusionsOur results make it possible to learn about the actual S/A practices used in Spain and to demonstrate a significant variability among the different units. This “state of the art” may lead to the preparation of clinical practice guidelines at a national level.40

Although S/A management is a continuously changing field, and although there are many areas which require more study, the creation of working groups and the preparation of guidelines or protocols resulting from the consensus reached by different units may lead to the reduction of variability in clinical practice and allow for an easier assessment of S/A guidelines in Spain.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Helena Viana, Paloma Lopez Ortego (Hospital Infantil Universitario La Paz, Madrid). Pilar Saenz Gonzalez, Raquel Escrig (Hospital Universitari i Politecnic La Fe, Valencia). Eva Bargalló Ailagas, Concepcio Carles (Hospital Universitari Josep Trueta, Girona). Laura San Feliciano, Ana Belén Mateo (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca). Inés Esteban Diéz, Rosa González Crespo (Hospital San Pedro de Logroño). Ersilia González Carrasco, Isabel de la Nogal Tagarro (Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganés). María Dolores Elorza Fernández, Nerea Benito Guerra (Hospital Universitario de Donostia). Salud Luna Lagares, Pedro Jiménez Parrilla (Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilla). Francesc Botet, Anna Ciurana, Rebeca Tarjuelo (Hospital Clinic de Barcelona). María José García Borau, Nuria Ibáñez (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona). Gloria Diáñez Vega (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz). María Arriaga Redondo (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid). Gloria Herranz, Virginia de la Fuente Iglesias (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid). Amaya Pérez Ocón, Sagrario Santiago Aguinaga (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra). Belén Martín Parra, Antonia Valero Cardona (Hospital General de Castellón). María Dolores Sánchez-Redondo, Antonio Arroyos Plana (Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo). Zenaida Galve Pradel, Nuria Clavero Montañés (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza). María Jesús Ripalda Crespo, Raquel Nogales Juárez (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares). Aintzane Euba Lopez, Sonia Fernández de Retana (Hospital Universitario de Álava). Mar Reyné Vergeli, Raquel Vidal (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona). Jose Luis Fernandez-Trisac, María Taboada (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña). Aurora Montoro Expósito, Fátima Camba Longueira (Hospital Vall d¿Hebron, Barcelona). Gonzalo Solís Sánchez (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo). María Purificación Ventura Faci, Marivi Mallen (Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza). Pilar Crespo Suárez, Elvira de Sola (Complexo Hospitalario de Pontevedra). Caridad Tapia Collados (Hospital General de Alicante). Isabel de las Cuevas, Beatriz Martín (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander). María Luz Couce Pico, Alejandro Pérez Muñuzuri, Salomé Quintáns (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago). Ana Melgar Bonis, Eugenia Bodas (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid). Ana Concheiro Guisan, Begoña Pérez Costas (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo).

Please cite this article as: Avila-Alvarez A, Carbajal R, Courtois E, Pertega-Diaz S, Muñiz-Garcia J, Anand KJS, et al. Manejo de la sedación y la analgesia en unidades de cuidados intensivos neonatales españolas. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:75–84.