The detection of child abuse is essential to allow adequate intervention with the aim of improving the situation of the patient and prevent its recurrence. Emergency departments (EDs) are the main point of entry to the health care system for many patients, yet several studies have demonstrated that detection of abuse could improve in the emergency care setting.1 The challenge posed by the differential diagnosis of many injuries, in which abuse may be confused with accidental, infectious or neurologic aetiologies, combined with the heavy workloads in EDs, results in failure to detect abuse in some instances, which may have significant consequences for the child. Due to these difficulties, different screening methods have been developed that are used routinely in in some countries,1,2 but not in Spain, where their application has not been studied. In this context, the Working Group on Abuse of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, SEUP) carried out a multicentre study to assess the tools used to screen for abuse in paediatric EDs in Spain.

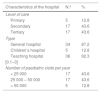

We designed an observational descriptive study with data collection by means of questionnaires. The study was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of the hospital. In November 2018, we contacted the directors of the EDs affiliated with the SEUP to request their participation in the study. We provided the link to an online questionnaire and sent 2 reminders by email in the 2 months that followed. The questionnaire included items about the characteristics of the ED, the methods used for detection of abuse, the existence and type of child abuse protocol and its availability. We contacted 80 directors and received responses from 39 of them (48.8%), corresponding to hospitals in 16 autonomous communities of Spain. Table 1 presents the characteristics of participating hospitals. In every hospital, abuse was suspected based on the findings of the history and the physical examination. None of the hospitals used a standardised abuse screening tool, and 5 (12.8%) were planning introducing one in the near future. Thirty-seven hospitals (94.9%) had a child abuse protocol in place in the emergency care setting (29 an in-house protocol and 8 a regional protocol) and 33 (84.6%) reported that the staff was acquainted with the protocol.

Characteristics of participating hospitals (n = 39).

| Characteristics of the hospital | N.º | % |

|---|---|---|

| Level of care | ||

| Primary | 5 | 12.8 |

| Secondary | 17 | 43.6 |

| Tertiary | 17 | 43.6 |

| Type | ||

| General hospital | 34 | 87.2 |

| Children’s hospital | 5 | 12.8 |

| Teaching hospital | 36 | 92.3 |

| [0.1–3] | ||

| Number of paediatric visits per year | ||

| < 25 000 | 17 | 43.6 |

| 25 000 – 50 000 | 17 | 43.6 |

| > 50 000 | 5 | 12.8 |

Based on our findings, we surmise that the suspicion of abuse in EDs depends exclusively on the ability of physicians to identify it, which in turn depends greatly on their training and experience on the subject. It is also worth noting that a large proportion of hospitals still did not fulfil the child abuse quality indicator established by the SEUP,3 which involves the existence of a child abuse protocol accessible to the ED staff, who in turn should be aware of its location. The lack of standardization involves a considerable heterogeneity in the approach to the identification of abuse, so that existing cases may go undetected, even severe ones.4 If we increase the frequency of early detection, the outcomes of these children may improve.4,5 A recent study found that the use of a screening checklist such as the SPUTOVAMO combined with a top-to-toe physical examination of all patients that visited the ED was a good method for detection of possible cases of abuse.6 On the other hand, Rumball-Smith et al. have advocated for the integration of a child abuse screening tool in the electronic health record system to be completed for every patient, as the authors observed an increase in the number of reported cases of suspected abuse.2 However, depending on the level of care and workload of each hospital, these strategies may be difficult to implement in Spain. One option, perhaps as a first step to improve detection, is to programme red flag alerts in the electronic health record system to be triggered with certain discharge diagnoses to alert the physician in charge of the potential of abuse before the patient is discharged. This would give the physician the opportunity to complete the child abuse checklist and review all the records shared in the system before discharging the patient, or to start an evaluation to address this suspicion. A similar option is being investigated for implementation in primary care clinics in Catalonia, and we believe that its implementation in EDs would be feasible. For this or other strategies, it is essential that patient records are available electronically and that the information contained in the electronic health records can be shared by the health care staff of different facilities while safeguarding confidentiality.

In conclusion, given the deficiencies observed in the EDs under study, it is our duty as specialist in paediatric emergency care to promote the knowledge and implantation of screening tools and to disseminate existing screening protocols to attempt to improve the care of potential victims of abuse and reduce its potential impact.

We thank the directors of the EDs of the following hospitals that participated in the study: Hospital de Barbastro, Hospital Comarcal San Juan de la Cruz de Úbeda, Hospital Virgen de Altagracia Manzanares, Hospital General San Jorge (Huesca), Hospital de Laredo, Hospital de Mendaro, Hospital Universitario San Agustín de Avilés, Hospital San Agustín de Linares, Hospital Ramón y Cajal (Madrid), Hospital Universitario Francesc de Borja (Gandía), Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Hospital General de Granollers, Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida, Hospital Royo Villanova (Zaragoza), Hospital Universitario Río Hortega (Valladolid), Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Hospital San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe (Bormujos), Hospital Infanta Cristina (Badajoz), Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (Cadiz), Hospital Universitario Basurto, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa, Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Hospital de la Santa Creu i de Sant Pau (Barcelona), Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía (Madrid), Hospital Universitario Son Espases (Majorca), Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias (Alcalá de Henares), Hospital Materno Infantil Teresa Herrera (A Coruña), Hospital Parc Taulí de Sabadell, Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucia (Murcia), Hospital Vall d'Hebron (Barcelona), Complejo Hospitalario Navarra, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (Las Palmas), Hospital Miguel Servet (Zaragoza), Hospital Universitario Cruces (Barakaldo), Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Madrid), Hospital Virgen de las Nieves (Granada), Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Murcia), Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (Barcelona).

Amaia Arbeloa Miranda, Ana Barrios, Ana Fábregas Martori, Ana I. Curcoy Barcenilla, Antonio Gancedo Baranda, Carme Pérez Velasco, Esther Tobarra Sanchez, Eva Moncunill Martinez, Elena Daghoum Dorado, Francesc Ferrés Serrat, Gemma Nadal Rey, Gerardo Suarez Otero, Glória Estopiñá Ferrer, Gloria López Lois, Isabel López Contreras, Juan Cozar Olmo, Julia Ruiz Jimenez, Karmele Díez Sáez, Leticia González Martin, Lorena Braviz Rodríguez, María Rimblas, Marisa Herreros Fernández, Noemí Franch Cabedo, Rafael Marañón Pardillo, Raquel Garcés Gómez, Teresa Vallmanya Cucurull.

Please cite this article as: Curcoy AI, Trenchs V. Cribado de maltrato en urgencias, una asignatura pendiente. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:337–338.

Appendix Alists the members of the Working Group on Abuse of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (SEUP).

Previous presentation: this study was presented at the XXIV Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría; Murcia, Spain; 2019.