With the advent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), countries had to make drastic and unexpected decisions for their populations. The Spanish government declared the state of alarm (14/03/2020–21/06/2020) and imposed strict measures (home confinement, remote working, closure of businesses, childcare centres, schools and universities) so that adults and children had to stay home for a long period of time.

Families experienced additional stress due to the fear of contagion,1 contracting the disease, the uncertainty surrounding the new virus, the death of loved ones and economic or job losses.2 Economic crises, infectious disease epidemics and significant disruption in the everyday life of the population affect mental health3 and increase the frequency of child abuse. The home environment worsens in small or crowded households, especially in unstructured situations, so the confinement to the home of these at-risk children, with no social contact beyond their family, deprived of the external support of teachers, paediatricians or other professionals, results in an increase in the cases of child abuse,4 although some studies suggest that more cases may go undetected when restrictions are in place, especially mild cases.5,6

Child abuse comprehends any action or omission that impinges on the rights or wellbeing of minors or threatens or interferes with their physical, mental or social development, independently of the form it takes or the medium in which it unfolds, including abuse committed through information technology, such as online abuse. There are four types of abuse: physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse and emotional abuse. When the state of alarm was lifted and restrictive measures de-escalated, we started to notice an increase in the number of visits related to child abuse in our paediatric emergency department. Given the absence of a specific child abuse register and previous data to use as reference, we decided to investigate whether there was a significant increasing trend in its incidence and whether there had been changes in the characteristics of child abuse cases relative to the same time period the year prior as a result of the confinement. If our impression were confirmed, we thought it would be an aspect of wellbeing sufficiently important to reach out to the scientific community and share the knowledge obtained on the subject with the ultimate purpose of developing early detection and prevention strategies.

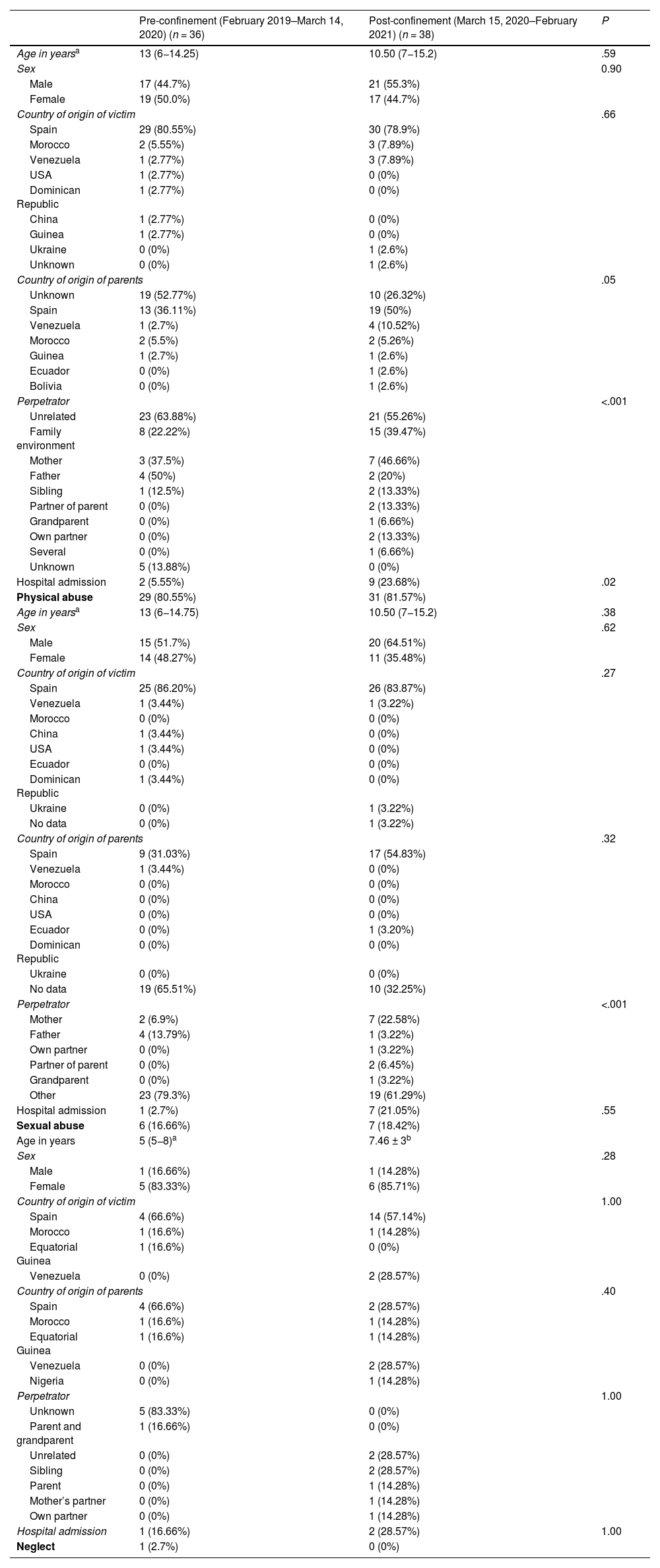

We conducted a retrospective descriptive and inferential study through the review of the health records of patients aged 0 to 18 years who received care for complaints related to child abuse in our department over a 24-month period. We compared the characteristics of the patients before the confinement (February 2019–March 14, 2020) and post confinement (March 15, 2020–February 2021), including the strict confinement period, during which there were no detected or suspected cases (14/03/2020–05/06/2020). There were no changes in the child abuse protocol applied during each of the periods (injury report form, consultation with social work services and police report, and involvement of a pathologist in cases of severe physical abuse and every case of sexual abuse). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of all the cases, and Table 2 the characteristics of the cases in each period and by type of abuse. During the post-confinement period, we found a change in the profile of the perpetrator, which used to be used to be someone outside the family before the confinement and someone in the household after the confinement, with an increase in the violence perpetrated by mothers and a decrease in the violence perpetrated by fathers, and a greater proportion of cases requiring hospital admission, differences that were statistically significant. When we analysed these same variables based on the type of abuse, we only found differences in the profile of the perpetrator in physical abuse, probably due to the sample size. Home confinement seems to increase the frequency of physical and sexual aggressions against children at the hand of family members, in addition to the severity of the assaults and the number that require hospitalization. Minors are vulnerable to crises and, while the impact of SARS-CoV-2 terms of the morbidity and mortality caused by the infection is lesser in this population, the consequences of the pandemic and confinement could have deleterious consequences on them and result in lifelong sequelae.3 The pandemic has highlighted the absence of a multidisciplinary public health approach, and the lack of early detection programmes, the lack of access to these services (leading to the underdetection of neglect) and the lack of preventive interventions in social and psychiatric care. Furthermore, given the observed increase in incidence, it is likely that we are now more aware of the problem and therefore reporting has increased. We believe that many of the variables analysed in this study would provide additional information and would be clinically relevant if child abuse registers were instituted in every care setting and level and studies of larger scope were conducted on the subject, so we take this opportunity to reach out and ask the scientific community to study these aspects.

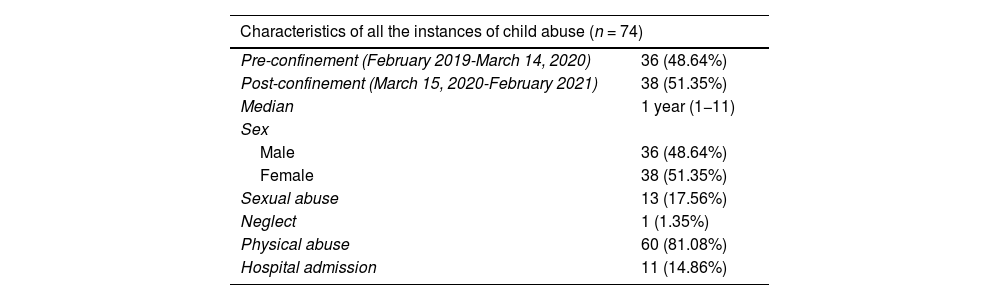

Description of the characteristics of child abuse cases overall.

| Characteristics of all the instances of child abuse (n = 74) | |

|---|---|

| Pre-confinement (February 2019-March 14, 2020) | 36 (48.64%) |

| Post-confinement (March 15, 2020-February 2021) | 38 (51.35%) |

| Median | 1 year (1−11) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 36 (48.64%) |

| Female | 38 (51.35%) |

| Sexual abuse | 13 (17.56%) |

| Neglect | 1 (1.35%) |

| Physical abuse | 60 (81.08%) |

| Hospital admission | 11 (14.86%) |

Description of the characteristics of child abuse cases in the pre-confinement and post-confinement periods.

| Pre-confinement (February 2019–March 14, 2020) (n = 36) | Post-confinement (March 15, 2020–February 2021) (n = 38) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yearsa | 13 (6−14.25) | 10.50 (7−15.2) | .59 |

| Sex | 0.90 | ||

| Male | 17 (44.7%) | 21 (55.3%) | |

| Female | 19 (50.0%) | 17 (44.7%) | |

| Country of origin of victim | .66 | ||

| Spain | 29 (80.55%) | 30 (78.9%) | |

| Morocco | 2 (5.55%) | 3 (7.89%) | |

| Venezuela | 1 (2.77%) | 3 (7.89%) | |

| USA | 1 (2.77%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Dominican Republic | 1 (2.77%) | 0 (0%) | |

| China | 1 (2.77%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Guinea | 1 (2.77%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ukraine | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Country of origin of parents | .05 | ||

| Unknown | 19 (52.77%) | 10 (26.32%) | |

| Spain | 13 (36.11%) | 19 (50%) | |

| Venezuela | 1 (2.7%) | 4 (10.52%) | |

| Morocco | 2 (5.5%) | 2 (5.26%) | |

| Guinea | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Ecuador | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Bolivia | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Perpetrator | <.001 | ||

| Unrelated | 23 (63.88%) | 21 (55.26%) | |

| Family environment | 8 (22.22%) | 15 (39.47%) | |

| Mother | 3 (37.5%) | 7 (46.66%) | |

| Father | 4 (50%) | 2 (20%) | |

| Sibling | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (13.33%) | |

| Partner of parent | 0 (0%) | 2 (13.33%) | |

| Grandparent | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.66%) | |

| Own partner | 0 (0%) | 2 (13.33%) | |

| Several | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.66%) | |

| Unknown | 5 (13.88%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hospital admission | 2 (5.55%) | 9 (23.68%) | .02 |

| Physical abuse | 29 (80.55%) | 31 (81.57%) | |

| Age in yearsa | 13 (6−14.75) | 10.50 (7−15.2) | .38 |

| Sex | .62 | ||

| Male | 15 (51.7%) | 20 (64.51%) | |

| Female | 14 (48.27%) | 11 (35.48%) | |

| Country of origin of victim | .27 | ||

| Spain | 25 (86.20%) | 26 (83.87%) | |

| Venezuela | 1 (3.44%) | 1 (3.22%) | |

| Morocco | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| China | 1 (3.44%) | 0 (0%) | |

| USA | 1 (3.44%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ecuador | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Dominican Republic | 1 (3.44%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ukraine | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.22%) | |

| No data | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.22%) | |

| Country of origin of parents | .32 | ||

| Spain | 9 (31.03%) | 17 (54.83%) | |

| Venezuela | 1 (3.44%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Morocco | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| China | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| USA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ecuador | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.20%) | |

| Dominican Republic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ukraine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| No data | 19 (65.51%) | 10 (32.25%) | |

| Perpetrator | <.001 | ||

| Mother | 2 (6.9%) | 7 (22.58%) | |

| Father | 4 (13.79%) | 1 (3.22%) | |

| Own partner | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.22%) | |

| Partner of parent | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.45%) | |

| Grandparent | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.22%) | |

| Other | 23 (79.3%) | 19 (61.29%) | |

| Hospital admission | 1 (2.7%) | 7 (21.05%) | .55 |

| Sexual abuse | 6 (16.66%) | 7 (18.42%) | |

| Age in years | 5 (5−8)a | 7.46 ± 3b | |

| Sex | .28 | ||

| Male | 1 (16.66%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Female | 5 (83.33%) | 6 (85.71%) | |

| Country of origin of victim | 1.00 | ||

| Spain | 4 (66.6%) | 14 (57.14%) | |

| Morocco | 1 (16.6%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 (16.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Venezuela | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| Country of origin of parents | .40 | ||

| Spain | 4 (66.6%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| Morocco | 1 (16.6%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 (16.6%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Venezuela | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| Nigeria | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Perpetrator | 1.00 | ||

| Unknown | 5 (83.33%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Parent and grandparent | 1 (16.66%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unrelated | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| Sibling | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| Parent | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Mother’s partner | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Own partner | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Hospital admission | 1 (16.66%) | 2 (28.57%) | 1.00 |

| Neglect | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

Previous meeting: The study was presented an oral communication at the as II Online Congress of the Asociación Española de Pediatría, June 3–5, 2021, with the title Cambios en las características del maltrato infantil durante la pandemia por SARS-Cov2 and signed by Maite Bayón Cabanes, Blanca Cano Sánchez De Tembleque, Elena Oyaga De Frutos, Ruth Púa Torrejón, María Jesús Ceñal González Fierro, Sara Chinchilla Langeber.