Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is rare in the paediatric population (incidence of 2.5%–5% of total paediatric cardiomyopathy cases).1 It is characterised by reduced diastolic volume with preserved systolic function and normal wall thickness.2 Most cases are idiopathic. Some of the known causes of RCM are genetic changes (mainly involving sarcomere protein genes) and infiltrative diseases (infrequent in children).3 There have been descriptions in the literature of pure RCM or mixed-phenotype RCM associated to hypertrabeculation (noncompaction cardiomyopathy [NCCM)) or hypertrophy.4 Medical treatment does not improve outcomes and there is rapid progression of pulmonary hypertension (PHT) and risk of sudden death.5 Therefore, performance of a heart transplant should be considered early on.

We have summarised the data as median and interquartile range (IQR).

We present a retrospective study conducted in 9 patients with RCM diagnosed in our hospital between September 2002 and September 2019. The median duration of follow-up was 95.57 months (IQR, 0.76–209.74) and the median age at diagnosis was 24.02 months (IQR, 0.00–176.03). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the patients. All had primary cardiomyopathy except 1 patient with suspected endomyocardial fibrosis secondary to schistosomiasis.6 Six patients presented a pure RCM phenotype (median age at diagnosis, 35.99 months; IQR, 1.81–176.03) and 3 a mixed RCM/NCCM phenotype (median age at diagnosis, 0.53 meses; IQR, 0–123.30); 2 had a family history of cardiomyopathy (1 of NCCM in a first-degree relative and 1 of RCM in first-degree and second-degree relatives). Five underwent genetic testing, with negative result in 1, detection of Alström syndrome in 1 and detection of a pathogenic variant in sarcomere protein genes in 3 (in the troponin T gene [TNNT2] in 1, and in the gene encoding the myosin heavy chain beta isoform [MYH7] in 3); 6 patients (4 with pure RCM and 2 with RCM/NCCM mixed phenotype) had onset with heart failure.

Demographic, electrocardiographic and haemodynamic characteristics of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 10.5 | 4.0 | 0.05 | 2.0 | 0.15 | 14.6 | 10.3 | 0.08 | 0.5 |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male |

| Type of RCM | Secondary Schisto | Primary | Primary | Primary | Primary | Primary | Primary | Primary | Primary |

| Phenotype | RCM | RCM | RCM/NCCM | RCM | RCM | RCM | RCM/NCCM | RCM/NCCM | RCM |

| CM FHx | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Genetic testing | Not done | done | Negative | done | Alström syndrome | Change in TNNT2 | done | Change in MYH7 | Change in MYH7 |

| Symptoms of HF | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Electrocardiogram | |||||||||

| HR (bpm) | ND | 87 | 83 | 84 | 125 | 75 | 98 | 103 | 100 |

| PR interval (ms) | ND | 130 | 160 | 145 | 121 | 130 | 192 | 164 | 110 |

| P-wave amplitude (mV) | ND | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| QRS (ms) | ND | 89 | 90 | 90 | 65 | 125 | 90 | 82 | 98 |

| QRS (axis) | ND | 90 | 10 | 30 | 67 | 147 | 20 | 79 | 117 |

| R amplitude, L II (mV) | ND | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| QTc | ND | 437 | 448 | 440 | 454 | 488 | 402 | 490 | 413 |

| Abnormal repolarization | ND | ST depression, inferolat | Inv. T-wave lateral leads | ST depression and inv. T-wave, inferolat | Inv. T-wave Lateral leads | Inv. T wave Lateral leads | No | No | Inv. T-wave anterolat. lead |

| P:QRS ratio, L II | ND | 0.36 | 0.5 | 0.36 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Arrythmias | FibA | AVB | VES | No | No | VT/SD | No | No | No |

| Echocardiography | |||||||||

| LA (z-score) | 5,20 | 2.39 | 5.57 | 2.09 | 4.26 | 4.56 | 4.60 | 4.20 | 2.60 |

| TI (mmHg) | 100 | 35 | 80 | 54 | 58 | 48 | 66 | 90 | 15 |

| LVEF (%) | 55 | 55 | 70 | 54 | 60 | 69 | 59 | 50 | 73 |

| E (m/s) | ND | 0.40 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 1.07 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1.50 |

| A (m/s) | ND | 0.58 | 0.32 | Not done | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.70 | 0.30 |

| E/A | ND | 0.69 | 2.60 | Not done | 4.50 | 3.69 | 2.22 | 1.10 | 5.00 |

| E/e’ | ND | 7.60 | 8.30 | 7.40 | 13.70 | 21.40 | 8.50 | 16.80 | 10.00 |

| Catheterization | |||||||||

| mPAP (mmHg) | 62 | 17 | 55 | 37 | Not done | 37 | 23 | 58 | Not done |

| LAP (mmHg) | 21 | 13 | 28 | 31 | Not done | 25 | 21 | 26 | Not done |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 24 | 15 | 27 | 21 | Not done | 32 | 28 | 28 | Not done |

| PVRI (UW·m2) | 23 | 2.2 | 12 | 6.1 | Not done | 6.0 | 5.7 | 6.1 | Not done |

| Current status | HLT/Dec | HT/Alive | HT/Alive | HT/Alive | TF/Alive | Dec | TL/Alive | HT/Alive | TL/Alive |

A, A-wave (transmitral flow); anterolat, anterolateral; AFib, atrial fibrillation; AVB, atrioventricular block; bpm, beats per minute; CM FHx, family history of cardiomyopathy; E, E-wave (transmitral flow); Dec, deceased; HF, heart failure; HLT, heart-lung transplant; HR, heart rate; HT, heart transplant; inferolat, inferolateral; inv., inverted; L, lead; LA, left atrium; LAP, left atrial pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; ND, not documented; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; QTc, corrected QT interval; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy; RCM/NCCM, mixed restrictive cardiomyopathy associated with hypertrabeculation; Schisto, schistosomiasis; SD, sudden death; TF, transplant-free; TI, tricuspid insufficiency; TL, transplant list; VES, ventricular extrasystoles; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

All patients for whom we could obtain electrocardiographic data (n = 9) had a high P:QRS ratio (median, 0.5 mV; IQR, 0.33–1.00) due to an increased P-wave amplitude (median, 0.40 mV; IQR, 0.20−0.60]) and a decreased QRS complex amplitude (median, 7.5 mV; IQR, 5–12). During the follow-up, 4 patients developed arrhythmias (median months from diagnosis): 1 with left hemiparesis to an episode of atrial fibrillation (36.50), 1 with frequent ventricular extrasystoles (9.30), 1 with atrioventricular block (60.65) and 1 with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and sudden death (0.76).

Eight patients had PHT, the degree of which was estimated based on the pressure gradient measured by echocardiography at the level of the dysfunctional tricuspid valve (median, 62 mmHg; IQR, 35–100). Seven patients underwent a haemodynamic assessment (Table 1).

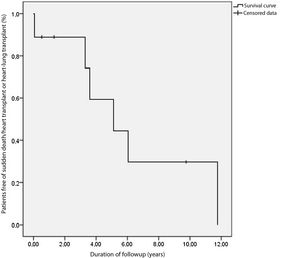

After a median of 7.9 years of follow-up, 3 of the patients were alive and transplant-free (Fig. 1), 5 had undergone a transplant and 1 died suddenly while on the transplant waiting list (case 6); 4 patients underwent transplantation at a median of 61.37 months post diagnosis (IQR, 39.72–141.04). The reason for transplantation was severe bilateral ventricular failure in 1 patient (case 2) that required venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and later biventricular support before transplantation. In 3 patients (cases 3, 4 and 8), the indication for transplantation was severe PHT and heart failure. Case 3 had suprasystemic pulmonary pressures and a pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) of 12 WU·m2, leading to initiation of left ventricular support to reduce pulmonary resistance before adding the patient to the heart transplant waiting list at 4 weeks (PVRI, 3.4 WU·m2) and preforming the transplantation after 11 months of circulatory support. Case 1 had been referred from another hospital and the evaluation at admission revealed severe and irreversible PHT (mean pulmonary artery pressure [mPAP], 62 mmHg; PVRI, 23 WU·m2), so the patient underwent a heart-lung transplant. All patients survived at 4 years from transplantation. Case 1 died at 4.4 years post transplantation due to chronic rejection of the lung transplant.

In conclusion, this article presents the largest case series to date in Spain of paediatric patients with RCM, an infrequent disease in children with a very poor prognosis and a 5-year overall survival/transplant-free survival of 20%. Placement of a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator for primary prevention should be contemplated in the early stages due to the high risk of arrhythmias, including atrioventricular block or sudden death.1 Pulmonary hypertension is a frequent complication that may contraindicate heart transplant, so early performance of heart transplant should be considered soon after detection of PHT, and also on account of the poor prognosis and lack of treatments. In patients with high PVRIs, ventricular support may be considered before transplantation. Due to the high incidence of complications and poor prognosis of RCM, it is particularly important to refer patients early for diagnosis and follow-up to highly specialised centres with paediatric arrhythmia and heart failure units that can also perform paediatric heart transplants.

Please cite this article as: Brunet-Garcia L, Roses-Noguer F, Betrián P, Balcells J, Gran F. Miocardiopatía restrictiva: la importancia de su diagnóstico precoz. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;95:368–370.