Primary immune thrombocytopenia, formerly known as immune thrombocytopenic purpura, is a disease for which the clinical and therapeutic management has always been controversial. The ITP working group of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology has updated its guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary immune thrombocytopenia in children, based on current guidelines, bibliographic review, clinical assays, and member consensus. The main objective is to reduce clinical variability in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, in order to obtain best clinical results with minimal adverse events and good quality of life.

La trombocitopenia inmune primaria, anteriormente conocida como púrpura trombocitopénica inmune, es una enfermedad cuyo manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico ha sido siempre controvertido. La Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátricas, a través del grupo de trabajo de la PTI, ha actualizado el documento con las recomendaciones protocolizadas para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de esta enfermedad, basándose en las guías clínicas disponibles actualmente, revisiones bibliográficas, ensayos clínicos y el consenso de sus miembros. El objetivo principal es disminuir la variabilidad clínica en los procedimientos diagnósticos y terapéuticos con el fin de obtener los mejores resultados clínicos, los mínimos efectos adversos y preservar la calidad de vida.

Primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an immune-mediated disorder characterised by the usually acute onset of a mainly peripheral thrombocytopenia with platelet counts of less than 100000/μL in children that do not have a history or illness that can explain the cytopenia, and with isolated haemorrhagic features (usually purpura) or without clinical manifestations.1 Its annual incidence is of 1 case per 10000 children, peaking at age 2–4 years, with no apparent differences between sexes. There is usually a history of viral illness or vaccination 1–3 weeks before onset.

The main feature in the pathogenesis of primary ITP is the loss of immune tolerance towards platelet-specific antigens. The initial evidence documented and established the role of the action of the effector arm of humoral immunity (specific autoantibodies) against platelets in the pathogenesis of the disease, but advances in immunology and their applications to the study of primary ITP have brought to light the important direct and indirect roles of cell-mediated immunity through T cell–B cell cooperation. Similarly, the prevailing view historically has been that thrombocytopenia results from the exclusive destruction of peripheral platelets, but at present it is believed that, at least in a certain percentage of cases, there is impairment in megakaryocytopoiesis, which would account for the absence of megakaryocytic hyperplasia observed in some children and the good response to treatment with thrombopoietic analogues.

The standardisation of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children was published in March 2009. The word “purpura” was eliminated from the name because cutaneous or mucosal bleeding symptoms are absent or minimal in some patients. The acronym ITP (Immune ThrombocytoPenia) (and the equivalent PTI in Spanish) was preserved due to its widespread and time-honoured use.1

This consensus document also established a platelet count of 100000/μL as the threshold for diagnosis of ITP, since platelet counts between 100000 and 150000/μL are frequently found in healthy individuals and pregnant women. The classification of ITP was modified based on the natural history of primary ITP in children, characterised by the spontaneous resolution within 6 months in approximately two-thirds of children and a high probability of remission between 3 and 12 months2 or even later.

This was followed by the publication in January 2010 of the international consensus for the diagnosis and management of primary ITP.3 Primary ITP remains a diagnosis of exclusion. The main feature is an increased risk of bleeding. There is not an exact correlation between platelet counts and haemorrhagic manifestations, although the latter are more frequent with counts of less than 10000/μL. Most patients are asymptomatic or present with petechiae, haematomas or ecchymoses isolated to the skin or mucosas.4,5 However, some patients may present with more severe bleeding that may be cutaneous, mucosal, gastrointestinal or even intracranial (0.1–0.5%).6–9

In this new protocol, we have established the management of clinically relevant bleeding as the main goal of treatment, as opposed to bringing platelet counts to the normal range. It is important to avoid unnecessary treatments, which may have adverse effects, in oligosymptomatic patients, in pursuit of an adequate quality of life and the minimisation of the toxicity associated with treatment. The treatment of persistent or chronic primary ITP is complex, and we propose several alternatives.

This new protocol is an updated version of the primary ITP-2010 protocol.10

ObjectivesTo standardise the diagnostic criteria and protocols for the followup and treatment of primary ITP.

Diagnostic classification, criteria for clinical assessment and response to treatmentDiagnostic classification1Newly diagnosed primary ITPWithin 3 months of diagnosis.

Persistent primary ITPBetween 3 to 12 months from diagnosis, including:

- •

Patients not reaching spontaneous remission.

- •

Patients not maintaining complete response of therapy.

Patients that continue to have thrombocytopenia past 12 months from diagnosis.

Criteria for clinical assessment10See Table 1.

Criteria for clinical assessment.

| Asymptomatic |

| Cutaneous manifestations |

| Cutaneous-mucosal manifestations |

| Active bleeding |

| Epistaxis requiring nasal packing |

| Gross haematuria |

| Gross gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Menorrhagia |

| Severe gum bleeding |

| Any bleeding likely to require a red blood cell transfusion or to cause severe organ damage |

Source: Monteagudo et al.10

See Table 2.

Criteria for assessing response to treatment10See Table 3.

Criteria for assessing response to treatment.

| Complete response. Platelet count ≥100000/μL persisting for more than 6 weeks after discontinuation of treatment |

| Partial response. Platelet count between 30000 and 100000/μL that constitutes an increase relative to baseline persisting for more than 6 weeks after discontinuation of treatment |

| No response. No changes in clinical or biological features |

| Transient response. Initial improvement (clinical or biological) followed by development of new symptoms or a platelet count of less than 30000/μL in the first 6 weeks after discontinuation of treatment |

| Relapse. Platelet count of less than 30000/μL more than 6 weeks after discontinuation of treatment following a complete or partial response |

Source: Monteagudo et al.10

All patients with thrombocytopenia should undergo a thorough history-taking and physical examination to rule out other blood disorders or situations that could cause secondary thrombocytopenia.

We recommend performing the diagnostic tests detailed in Table 4, which are considered essential.3,10–12

Tests recommended for diagnosis.

| Complete blood count and reticulocyte count: consistent with isolated thrombocytopenia |

| Peripheral blood smear with morphology assessed by an experienced staff: normal morphology |

| Screening of haemostasis: prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, factor I assay |

| Blood group and Rh typing, direct Coombs test |

| Immunoglobulins |

| Serologic evaluation for cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, herpes simplex virus, human herpesvirus 6, HIV, hepatitis B and C |

| Blood chemistry: glutamic-oxaloacetic acid transaminase (GOT), glutamic-pyruvic acid transaminase (GPT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), glucose, urea, creatinine |

| Urine sediment test |

| Bone marrow examination in sample obtained by puncture and aspiration, indicated in all children presenting any of the following: atypical clinical manifestations, detection of other cytopenias in the complete blood count, nonresponse to first-line treatment and untreated patients that do not exhibit spontaneous remission |

Indicated in patients that do not exhibit spontaneous remission or do not respond to treatment. We recommend the following tests:

- •

Bone marrow examination, from a puncture and aspiration sample, if not performed previously. Consider performance of bone marrow biopsy, immunophenotyping and karyotyping to complete the evaluation.

- •

Lymphocyte subsets.

- •

Antinuclear antibodies and optionally other autoimmunity tests.

See Table 5.

General recommendations.

| At diagnosis, consider hospital admission in patients with active bleeding, risk factors for haemorrhage or with platelet counts ≤20000/μL |

| Avoid injection of intramuscular drugs and phlebotomy procedures in vessels that are difficult to compress |

| The use of acetylsalicylic acid or its derivatives is contraindicated, administer only if other drugs that may alter platelet aggregation are strictly necessary (antihistamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) |

| Sports: restrict based on clinical manifestations and risk of trauma |

| Antifibrinolytics: tranexamic acid.13 Especially in patients with active bleeding and mucosal bleeding. Contraindicated in case of haematuria. It can be administered orally at a dose of 20mg/kg/8–12h or intravenously at a dose of 10mg/kg/8–12h |

Patients with newly diagnosed primary ITP1 may present with haemorrhagic manifestations of variable severity usually depending on the platelet count, usual activity of the patient and the presence of other factors that may play a role in haemostasis. The entire constellation of clinical and physiological features needs to be taken into account to establish an adequate therapeutic approach. We have decided to classify patients into various groups based on the clinical features and risk factors for bleeding with the aim of selecting the most appropriate therapeutic approach.3,10,11,14–19

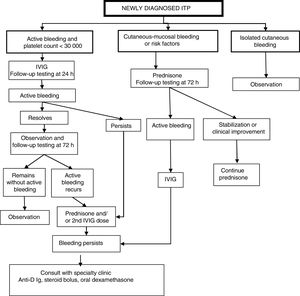

Classification of patients and management protocol (Fig. 1)Patients with active bleeding and platelet count of less than 30000/μLWe propose administration of 1 dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) followed by a new assessment at 24h: Fig. 1

- •

If active bleeding persists, add a corticosteroid (prednisone o methylprednisolone) and/or a second dose of IVIG.

- •

If symptoms resolve, assess patient again at 72h and,

- •

If clinical improvement persists, keep patient under observation;

- •

If active bleeding recurs, initiate steroid therapy (prednisone o methylprednisolone) or administer a second dose of IVIG.

If active bleeding continues after the above treatment, we recommend consulting with a specialty paediatric haematology unit about the potential administration of anti-D immune globulin (if the patient is Rh+),17 a steroid bolus or oral high-dose dexamethasone.20

Patients with cutaneous-mucosal bleeding or haemorrhagic risk factorsWe propose initiating treatment with steroid therapy (prednisone or methylprednisolone). If the patient progresses to active bleeding, administer a dose of IVIG and proceed with the sequence specified for patients with active bleeding in the previous section.

Patients with exclusively cutaneous bleedingWe propose watchful waiting and testing at regular intervals with subsequent management based on the symptoms and laboratory findings.

Persistent and chronic primary ITPPatients with symptomatic chronic primary ITP that need sequential or permanent treatment ought to be monitored fully by or in coordination with hospitals that have a specialised paediatric haematology unit.

Patients with persistent and chronic primary ITP may have manifestations of variable severity, usually in relation to the platelet count, usual activity of the patient and presence of other factors that influence haemostasis. All clinical and laboratory features must be taken into account to establish an appropriate treatment plan to help the patient have a normal life as possible and minimise the adverse effects of treatment19,21 while awaiting remission.3,10,11,22,23 There is widespread consensus in the literature that platelet count of 300000 is a reasonable threshold to expect the maintenance of a normal everyday, and therefore this parameter has been established as one of the determining factors in the initial decision-making process. Nevertheless, the lifestyle, usual activity, clinical manifestations and risk factors for bleeding of each individual patient are also key, especially when it comes to prescribing specific interventions.

Patient classification and management protocol (Fig. 2)Patients with a stable platelet count of more than 30000/μLWe recommend maintaining the patient under observation while performing whichever tests the physician in charge considers necessary.

Patients with a platelet count of less than 30000/μLAdequate treatment planning requires consideration of potential risk factors associated with the patient's age, physical activity, household environment and access to health care. We recommend maintaining patients without episodes of active bleeding or risk factors for bleeding under observation. For all other patients, we recommend:

- •

Patients with persistent ITP: during bleeding episodes, administration of IVIG,3,10,11,14,15,23 anti-D Ig,3,15,17 oral prednisone or dexamethasone.24–27 If the patient continues to have episodes of bleeding, we recommend referral to a speciality clinic for evaluation and assessment of other treatment options.

- •

Patients with chronic primary ITP and persistent symptoms: we recommend administration of thrombopoietin analogues as first-line treatment,28–36 reserving steroid therapy or IVIG for treatment of episodic bleeding. Only if first-line treatment fails, consider second-line treatments such as splenectomy,3 rituximab11,22,33,37–39 or other immunosuppressive drugs, such as mycophenolate.33,40,41

See Table 6.

Recommendations for the management of life-threatening emergencies, special risk situations and scheduled splenectomy.

| Life-threatening emergencies |

| CNS bleeding |

| Other life-threatening haemorrhages |

| Successive administration of: |

| 1. IV methylprednisolone 10mg/kg |

| 2. IV gamma globulin 400mg/kg |

| 3. Platelets 1 unit/5–10kg/6–8h |

| 4. IV gamma globulin 400mg/kg |

| 5. Urgent splenectomy: consider on a case-by-case basis |

| Special risk situations |

| Head trauma, polytrauma and urgent surgery |

| Administration of IVIG at 0.8–1g/kg if platelet count <50000/μL and platelets if count <10000/μL |

| Scheduled surgery (assess haemorrhagic risk based on procedure) |

| IVIG 0.8–1g/kg if platelet count <50000/μL |

| Scheduled splenectomy |

| IVIG 0.8–1g/kg if platelet count <20000/μL |

| Early clamping of splenic artery |

Corticosteroids are historically the first-line treatment of primary ITP.

Dosage- •

Oral prednisone or intravenous methylprednisolone, split into 3 doses given after breakfast, lunch and dinner. Dose of 4mg/kg/day (to a maximum of 180mg/day) given for 4 days, followed by 2mg/kg for 3 days and discontinuation.

- •

Steroid bolus: methylprednisolone 30mg/kg/day to maximum of 1g, for 3 days, infused over 2h. It requires monitoring of blood pressure and glucose in urine.

- •

Oral dexamethasone: 0.6mg/kg/day to a maximum of 40mg given in a single dose for 4 days. It is usually given in monthly cycles.

The main toxic effects of steroids are hyperglycaemia and hypertension, mood changes and sleep disturbances, and, in case of prolonged treatment, Cushing syndrome, osteoporosis and growth retardation. Due to their immunosuppressive activity, steroids also increase the susceptibility to infection.

Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG)Dosage- •

0.8–1g/kg single dose given as a continuous intravenous infusion over 6–8h, with a slower infusion rate at initiation; we recommend adhering to the infusion rate schedule specified for the product that is administered.

- •

Anaphylaxis, in patients with IgA deficiency: we recommend having ready for immediate use the specific treatment and resuscitation drugs (adrenaline).

- •

Headache, nausea, vomiting (we recommend slowing the infusion rate).

- •

Low-grade fever/fever.

- •

Alloimmune haemolytic disease.

- •

Aseptic meningitis.

Blocking of macrophage Fc receptors by anti-D-coated red blood cells.

Dosage- •

50–75μg/kg/day in a single IV dose. Infusion over 1h in a physiological saline solution. We recommend previous administration of paracetamol.

Immune haemolytic anaemia and, since this is a blood derivative, there is a risk of transmission of infectious diseases. There are also reported cases of hepatitis C transmission.

We recommend the following tests: haemoglobin, direct Coombs, reticulocyte count and indirect bilirubin. We recommend against giving another dose (2–4 weeks later) in case of indirect bilirubin greater than 1.5mg% and a proportion of reticulocytes greater than 5% with bilirubin elevation or choluria, or a decrease in haemoglobin greater than 2g.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonistsThe thrombopoietin analogues, eltrombopag and romiplostim, are two molecules with different characteristics that induce thrombopoiesis through the stimulation of their respective receptors. They have been developed in recent years and clinical trials have demonstrated that they can achieve a sustained response in a high percentage of cases in which treatment with other drugs (steroid therapy, IVIG) fails or does not achieve a sustained response off therapy. At present, their summaries of product characteristics include the indication for treatment of chronic primary ITP in children aged more than 1 year and adults.

The introduction of thrombopoietin analogues has significantly improved symptoms and quality of life in patients with an acceptable safety profile.22,28,29,32,36

Their place in the treatment pathway of chronic ITP has moved ahead of treatments that may carry greater risk, such as splenectomy and rituximab, all the more so in children, in whom cases of late spontaneous remission of disease have been documented. Clinical trials have shown that patients that do not respond to one of these drugs may respond to the other.

Treatment with thrombopoietin receptor agonists should be prescribed and managed in paediatric haematology units.

Mechanism of action- •

Romiplostim is a recombinant protein with 2 thrombopoietin receptor-binding domains. It stimulates megakaryocyte growth and maturation by binding the Mpl receptor, in the same fashion as endogenous thrombopoietin (TPO), and through the JAK2, STAT5, P38 MAPK and AKT pathways.

- •

Eltrombopag is a small, orally-active nonpeptide molecule that binds the transmembrane portion of the TPO receptor at a different site than endogenous TPO, upon which it activates the JAK2/STAT signalling pathway that stimulates platelet production.

Eltrombopag and romiplostim are indicated for use in children aged more than 1 year with chronic primary ITP in whom other treatments of primary ITP have failed.

DosageRomiplostim- •

1 dose per week administered subcutaneously.

- •

Initial dose: 1μg/kg/week.

- •

Dose titration: increase of 1μg/kg/week (to a maximum of 10μg/kg/week) until the platelet count exceeds 50×109/L.

- •

The median weekly dose required is of about 5μg/kg. The response to treatment peaks 2 weeks after the first dose.

- •

If the platelet count is greater than 150×109/L in 2 consecutive weeks, lower the dose by 1μg/kg. Once the platelet count exceeds 250×109/L, treatment should be suspended temporarily to be restarted with a dose 1μg/kg lower than the last dose once the platelet count drops below 150×109/L.

- •

Platelet counts must be measured weekly until the count stabilises, and monthly thereafter.

- •

Single dose daily administered orally.

- •

Initial dose:

- •

Children aged 1–5 years: 25mg/day.

- •

Children aged 6–17 years: 50mg/day.

- •

In patients of East Asian origin or those with evidence of moderate to severe liver damage: 12.5–25mg/day.

- •

- •

Dose titration: if 2 weeks after initiating treatment the platelet count is less than 50×109/L, increase the dose by 12.5mg (age <6 years) or by 25mg (age ≥6 years). Further dose adjustments following this pattern must be made at least 2 weeks apart until a platelet count greater than 50×109/L is achieved, never exceeding the maximum dose of 75mg/day.

- •

To facilitate absorption, eltrombopag must be taken on an empty stomach, and since eltrombopag is a polyvalent cation chelator, it should be taken at least 4h after and 2h before consumption of any antacid medications, calcium (dairy products) or supplements containing iron, magnesium, selenium, zinc or aluminium. Failure to comply with this precaution is a frequent cause of nonresponse to treatment.

Both eltrombopag and romiplostim have proven effective by increasing platelet counts in approximately 80% of patients with primary ITP refractory to other treatments, and in half of cases the response is usually stable with minimum dose changes.

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the use of a second thrombopoietin receptor agonist when treatment with the first one has failed.

Although the initial response to treatment with these drugs is usually quick (1–2 weeks), the platelet count tends to drop 2 weeks after treatment discontinuation, so that these drugs need to be administered continuously, which is not only costly but also concerning on account of the lack of evidence on the safety of their long-term use. The recent literature has included the description of cases where it was possible to withdraw the TPO receptor agonist with maintenance of a stable platelet count.

Discontinuation of treatmentTreatment should be discontinued if the platelet count does not increase to a level deemed sufficient to prevent clinically significant bleeding after 4 weeks of treatment at the maximum dose (romiplostim: 10μg/kg/week; eltrombopag: 75mg/day).

Adverse effectsThe adverse events reported in patients treated with TPO receptor agonists have mostly been mild, the most frequent ones being headache and upper respiratory tract infection.

When it comes to eltrombopag, reported adverse events have included transaminase and bilirubin elevation (reversible by discontinuation of the drug), which therefore should be monitored 2 weeks before initiation, every 2 weeks during dose titration and monthly in patients with stable platelet counts.

Infrequent adverse events have been described for both drugs, such as an increase in reticulin in the bone marrow (reversible by discontinuation of the drug) and thrombotic complications (more frequent in adults, although paediatric cases have also been reported), so caution should be exerted when administering these drugs to patients with known risk factors for thromboembolism; there is also a very low risk of progression to blood cancers and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Two cases of cataracts have also been reported in the literature in patients treated with a combination of eltrombopag and steroid therapy, as well as 2 cases of patients that developed anti-romiplostim antibodies with no evidence of cross-reactivity with endogenous TPO.

SplenectomyIndications- •

Recently diagnosed or persistent primary ITP: in case of emergent life-threatening bleeding that is not responding to previous treatment.

- •

Chronic primary ITP:

- •

In case of emergent life-threatening haemorrhage.

- •

Consider in patients aged more than 5 years who are symptomatic, have not responded to previous treatment and in whom the disease is interfering with normal daily activity, with onset more than 2 years prior.

- •

Vaccination against pneumococcus, meningococcus and Haemophilus influenzae.

- •

Daily oral penicillin or amoxicillin for a minimum of 2 years post surgery.

- •

In case of fever without source, initiate antibiotherapy covering pneumococcus, H. influenzae and meningococcus.

There are limited data on its use for treatment of primary ITP in the paediatric population, although it may be effective in patients with less severe forms of chronic ITP or patients with autoimmune cytopenias (Evans syndrome or autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome). The recommended dosage is of 20–40mg/kg/day, given in 2 doses. The overall response rate can reach up to 50–60%, with a time to response ranging between 4 and 6 weeks. It is well tolerated, and the main side effects are headache and gastrointestinal disturbances.33,40,41

Rituximab. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodyRituximab has been used in adults and also children, although there are fewer published data for the paediatric age group.33,37,42 The proportion of patients that respond to treatment range between 30% and 60% depending on the duration of follow-up. Infusion of rituximab requires monitoring for acute immune-mediated reactions that may be severe in some cases. There is a risk of infection due to prolonged depletion of B cells, and at present rituximab continues to be under surveillance due to reports of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after use of rituximab for treatment of other diseases.43 Its use would be compassionate, as this indication is not included in the summary of product characteristics.

Conflicts of interestEmilio Monteagudo: consultant in Amgen advisory board.

Itziar Astigarraga has been a consultant on Nplate-Amgen advisory boards.

Áurea Cervera has been a consultant on two Nplate-Amgen advisory boards and received fees from Novartis for giving a talk at a conference on primary ITP.

M. Angeles Dasí has been a consultant on Revolade – Novartis and Nplate-Amgen advisory boards.

Ana Sastre has been a consultant on Revolade – Novartis and Nplate-Amgen advisory boards. She has participated in an online education programme on paediatric primary ITP sponsored by Novartis and given talks in several seminars sponsored by Novartis.

Rubén Berrueco has been a consultant on a Revolade – Novartis advisory board and participated in an online education programme on paediatric primary ITP sponsored by Novartis.

José Luis Dapena has been a consultant on Revolade – Novartis and Nplate-Amgen advisory boards and has participated in an online education programme on paediatric primary ITP sponsored by Novartis.

Please cite this article as: Monteagudo E, Astigarraga I, Cervera Á, Dasí MA, Sastre A, Berrueco R, et al. Protocolo de estudio y tratamiento de la trombocitopenia inmune primaria: PTI-2018. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;91:127.

Previous presentation: This study was submitted and presented at the XI National Congress of the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátricas; May 31–June 2, 2018; Alicante, Spain.