Sjögren syndrome (SjS) is a systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) characterised by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands (mainly salivary and lachrymal), asthenia and tissue and organ destruction of variable degree. It can be primary or secondary, and affects 10% to 18% of patients with other autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis.

It is one of the most frequent SAD. Primary SjS has an incidence of 6 to 10 per 100.000 people and a prevalence of 40 to 70 per 100.000 people. It is more frequent in women (ratio 6–9:1) between 30 to 50 years. Only 1% of the patients have pediatric-onset.1 Its low frequency in paediatrics and the scarce number of publications in Spanish might explain that a number of paediatricians are not familiar with this disease, which motivated us to review the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 9 patients diagnosed with JSjS in our hospital between 2011 and 2023 (Table 1)

Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 9 patients with juvenile Sjögren syndrome at diagnosis.

| Variables | Patients with JSjS (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 8 |

| Male | 1 | |

| Age at diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 12.3 ± 1.1 | |

| Reason for consultation | No symptoms | 5 |

| Xerophthalmia | 2 | |

| Xerostomia | 0 | |

| Recurrent parotitis | 1 | |

| Arthritis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | 1 | |

| Arthralgia | 4 | |

| Asthenia | 2 | |

| Fever | 1 | |

| Recurrent oral aphthae | 2 | |

| ESSDAIa (mean ± SD) | (3.1 ± 3.5) | |

| - No activity (ESSDAI = 0) | 2 | |

| - Without high activity in any domain | 6 | |

| - High activity in at least one domain | 1 | |

| Laboratory features | Cytopenia | 2 |

| Rheumatoid factor (+) (≥14 IU/mL) | 7 | |

| ANA (+) | 7 | |

| SSA/Anti-Ro (+) | 8 | |

| SSB/Anti-La (+) | 5 | |

| ESR (mm/h, mean ± SD) | (29.4 ± 24.2) | |

| - Normal | 5 (12.4 ± 4.8) | |

| - Elevated (≥25 mm/h) | 4 (50.7 ± 21) | |

| C-reactive protein ≥1 mg/dL | 2 | |

| Elevated IgG (mg/dL, mean ± SD) | 8 (1.817 ± 572) | |

| Urinary changes | 1 | |

| Diagnostic tests | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca in at least 1 eye | 6 |

| Positive Schirmer’s test ( ≤5 mm/5 min) in at least one eye | 3 | |

| OSSb ≥5 in at least one eye | 2 | |

| Salivary gland ultrasound | ||

| - Normal or nonspecific changes | 4 | |

| - Abnormal (OMERACT SGUSc 2/3) | 5 | |

| Focal lymphocytic sialadenitis in salivary gland biopsy | 9 | |

The disease was more frequent in women (8/9), and the mean age at diagnosis was 12.3 years. Five out of nine patients were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis and were referred due to the presence of autoantibodies found during the workup performed for variety of reasons. Among these patients, one had a history of self-limited episodes of mild bilateral parotid swelling that was not considered relevant by the family. Two out of nine patients had xerophtalmia, which was the reason for referral in one of them; one recurrent parotitis and one arthritis associated with thrombotic thrombocytoenic purpura (TTP). When the history taken at admission was reviewed, she reported xerostomia of several months for which se had not sought medical care. Table 1 details other minor symptoms in the patients.

In regards to laboratory tests, 8/9 tested positive for anti-SSA/Ro antibodies, 7/9 for rheumatoid factor (RF), 7/9 for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and 5/9 for anti-SSB/La antibodies. Two patients had cytopenias at disease onset, one of them secondary to TTP.

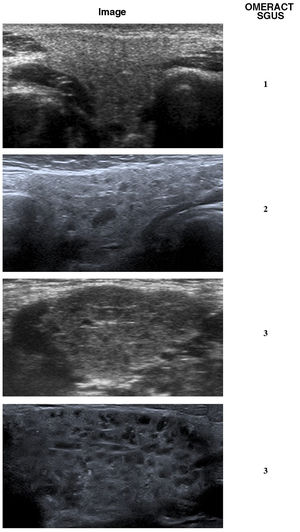

Table 1 presents the results of the ophthalmological evaluation and the salivary gland ultrasound (SGU). Fig. 1 shows the changes observed in the SGUS.

Ultrasound features characteristic of the changes found in the salivary glands of patients with juvenile Sjögren syndrome. All images are of the submandibular gland, and the abnormalities were bilateral. The assessment of the changes on a scale from 0 to 3 was performed using the Salivary Gland Ultrasound Scores (SGUS), a scoring system developed by Outcome measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) to measure sonographic salivary gland abnormalities in patients with Sjögren syndrome. The analysed variables include the inhomogeneity of the parenchyma, the presence of anechoic/hypoechoic areas (micro- or macrocysts) and the echogenicity of the surrounding tissue (normal or fibrotic).

Juvenile SjS is an olygosymptomatic disease: although only 2 of the 9 patients referred xeropthalmya, 6 had keratoconjunctivitis sicca, and while only 5 had abnormal sonographic features, all 9 had focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis.

The presentation of JSjS is different from the presentation in adults, and currently there are no validated classification criteria available for the paediatric population. The predominant feature in adults is dryness (xerostomia and xerophthalmia), which are rare in adolescents,2 while parotitis is the most frequent symptom in children,2,3 a finding that was not corroborated in this series. In 2017, the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism jointly updated their classification criteria for SjS,4 requiring a score of 4 points or greater in the assessment of the five following variables: (1) focal lymphocytic sialadenitis and focus score of ≥1 foci/4 mm2 in a minor salivary gland biopsy specimen (3 points); (2) Anti-SSA/Ro positive (3 points); (3) ocular staining score [OSS] ≥5 in at least 1 eye (1 point); (4) Schirmer's test≤5 mm/5 minutes in at least 1 eye (1 point); (5) Unstimulated whole saliva flow rate ≤0.1/minute (1 point).

None of these variables refers directly to the presence of oral or ocular dryness, and the criteria may be applicable to the paediatric population, although their use requires the performance of a minimally invasive outpatient procedure, the minor salivary gland biopsy. In recent years, some authors have suggested that the SGU score (SGUS) combined with other criteria, such as positive autoantibody results and keratoconjunctivitis sicca, may replace the biopsy in adult patients5; in our series, however, 4 of the 9 patients had histological changes with a normal SGUS.

Laboratory criteria, such as positive results for anti-SSA/Ro and RF in absence of arthritis, are highly suggestive of JSjS and were key for suspecting the diagnosis in asymptomatic patients. When these tests are positive, especially in the presence of hypergammaglobulinaemia, the patient must be referred for an ophthalmological evaluation and SGU.

In 2021, Big Data Sjögren Project Consortium international multicentre register published the largest JSjS case series to date, including 158 patients younger than 19 years at disease onset.6 The most frequent symptoms at onset were salivary gland swelling (36%) and xerostomia/xerophthalmia, combined (24%) or isolated (22%). It is remarkable that 70 to 80% of the patients of this series reported sicca syndrome at disease onset, which resembled the published data on adults more than the data in paediatric case series like the one presented here.

Disease awareness and close collaboration with primary care paediatricians, Ophthalmology services caring for patients with keratoconjunctivitis, and Maxillofacial surgery units following children with recurrent parotitis are crucial for early diagnosis. This strategy would allow better control of the disease, and anticipation of fetal morbidity, including pregestational obstetric referral to reduce the complications associated with neonatal lupus.