Teenage pregnancy is considered an important public health problem, as it has a considerable social, personal and medical impact in the adolescent population. In Spain, the rates of pregnancy in adolescents in 2010 were 2.2 per 1000 individuals aged 15 years and 20.7 per 1000 individuals aged 19 years.1

The main goal of our study was to analyse the reasons why female adolescents that received a pregnancy diagnosis initially sought medical care. As detection of pregnancy in this age group is challenging, paediatricians tend to not suspect it, and early diagnosis is essential for adequate management of the patient.

Another objective was to assess the risk factors in these patients to propose hypotheses that could guide the development and implementation of effective preventive measures in Spain.

We conducted a retrospective and descriptive study of all the pregnancies diagnosed in a tertiary children's hospital in the Community of Madrid in a period of over 11 years (January 2005 through January 2017, both included).

We collected the available data regarding past medical and psychiatric history, substance use, home and social environment, psychomotor development, academic performance and country of origin.

We also collected all the available information on the sexual history of these patients, such as pregnancies past and in the 6 years that followed, engagement in unprotected sex after the pregnancy, and the proportion of pregnancies under study that ended with voluntary termination of pregnancy (VTP) or birth of a baby in those patients that were followed up at our clinic.

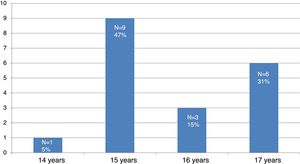

A total of 19 pregnancies were detected in girls aged 14–17 years. The mean age was 15.7 years and the median and mode were 15 years (Fig. 1).

Seven patients sought care for decompensation of a pre-existing psychiatric disorder, 8 for gastrointestinal symptoms (3 for vomiting and diarrhoea and 2 for abdominal pain), 3 for amenorrhoea in the context of an eating disorder, and 1 for abundant vaginal bleeding. Only 1 sought care for suspected pregnancy. Two of the patients had previously sought care for the same manifestations, with the pregnancy remaining undetected.

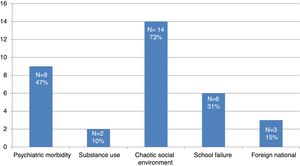

Forty-seven percent of these pregnant adolescents (9/19) had a history of psychiatric disorders (eating disorder in 4, depressive disorder in 3, and behavioural disorder in 2). There were problems in the social environment of 14, substance use in 2, and school failure with the patient dropping out of school in 6. Three were immigrants, all of them from South America (Fig. 2).

Pregnancy was diagnosed through detection of β-hCG in urine in 18 patients and in blood in 1. Of the pregnancies for which follow-up data were available (15/19), 11 ended with VTP, and 4 reached full term with delivery of healthy babies.

When it came to sexual history and followup, 2 of the patients had been pregnant in the past, 36% (7 patients) became pregnant again in the 6 years that followed, and 3 sought emergency contraception at later dates after having unprotected sex.

Most of the works in the literature we reviewed identified socioeconomic disadvantage as an important contributor to teenage pregnancy.2,3 In the cases reviewed in this study, conflict in the home or social environment and a history of psychiatric morbidity were risk factors present in large proportions of the sample.

The design of our study does not allow for calculating incidence or prevalence rates, but most patients sought care for symptoms that were either nonspecific or could be attributed to underlying disorders (for instance, amenorrhea, which can be a manifestation of eating disorders), and only one patient suspected pregnancy, which demonstrates that diagnosis of teenage pregnancy is challenging and, while infrequent, pregnancy should be included in the differential diagnosis of girls in this age group, especially those that present with abdominal pain or decompensations of pre-existing psychiatric disorders.

The literature suggests that a combination of multiple strategies such as educational interventions and the use of contraceptive methods can reduce the rate of teenage pregnancy.4 However, in Spain, despite the unrestricted availability of contraceptive methods and the wide diffusion of information, the rate of teenage pregnancy has remained constant in recent decades, with mild fluctuations up and down but no significant changes overall.

These data suggest that while the widespread implementation of a combination of strategies mentioned above is important, the effectiveness of these general interventions may not be homogeneous throughout the entire population,5,6 so that specific interventions targeting high-risk groups may be needed, with more individualised education and followup and adaptation to the recipients’ social and cultural context.

We want to thank the Coding and Records Department of the Hospital Niño Jesús, which allowed the performance of this study.

Please cite this article as: Palomino Pérez LM, Pérez Suárez E, Cabrero Hernández M, de la Cruz Benito A, Cañedo G. Embarazo en adolescentes en los últimos 11 años. Motivos de consulta y factores de riesgo. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89:121–122.