Moderate-late preterm (MLPT) infants amount to 80% of all infants born preterm. They exhibit a lesser degree of myelinization and sulci development and a reduced cerebral volume1,2 compared to term infants, differences that are maintained compared to term infants of the same corrected age,3 suggesting that MLPT birth could be a cause of neurodevelopmental disorders in the short and long term.4

The evidence that has emerged on the increased vulnerability of MLPT infants in recent years has contributed to the application of patient- and family-centred care in this subset of preterm infants. There are no current data on the subject in the Spanish population, and for most of Spain,5 it is also not known whether the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has led to changes in this type of care.

We conducted a descriptive study by submitting an online questionnaire to the members of the Sociedad Española de Neonatología (Spanish Society of Neonatology, SENeo). We collected demographic data for the respondents and different aspects regarding the management of MLPT infants in the delivery room and the neonatal unit (Table 1).

If we received more than one response from a single facility, we only included the one received first in the study. We received 117 responses corresponding to 87 hospitals representing every autonomous community of Spain with the exception of the autonomous city of Melilla. Of all responses, 95.4% were submitted by neonatologists or paediatricians, 3.5% by nurses and 1.1% by paediatrics medical residents.

In the delivery room, delayed cord clamping was practiced in all MLPT newborns that do not require resuscitation in 72.1% of facilities, while 11.6% of hospitals only practiced it in late preterm newborns, 5.8% practiced it in every case and 10.5% did not practice it yet. Kangaroo care practices did not change during the pandemic, with 50.6% of facilities practicing it in MLPT newborns that do not require resuscitation, 5.7% in every case, 36.8% only in late preterm newborns and 6.9% not having introduced it yet. Some facilities restricted access to the delivery room to the partner of the mother, with the overall access (for all types of delivery) decreasing from 42.5% to 34.5% (P = .27), and the presence of the partner banned in every case in 5.7% of facilities, compared to only 1.1% before the pandemic (P = .09).

When it came to rooming-in, practices in MLPT newborns have not changed much, although the frequency of rooming-in has decreased from 50.6% to 47.1% (P = .65) in hospitals that practice rooming-in in newborns delivered at or after 35 weeks, while it remained stable in hospitals that practice it in every MLPT infant. If the mother required admission to the intensive care unit, 3.4% of hospitals allowed contact with the infant during the pandemic, compared to 11.5% before (P = .04). The percentage of hospitals that did not allow it increased by 6% during the pandemic to 65.5% (P = .4).

Initiation of feeding at the breast remained stable in MLPT infants; during the pandemic, 55.2% of hospitals practiced it all MLPT infants, 14.9% in those born at or after 33 weeks, 24.1% in those born at or after 34 weeks and 5.7% in infants born at or after 35 weeks.

When it came to post-discharge hospital-level care, 86.2% of facilities did not offer these services, 6% offered it to moderately preterm infants and 8% to MLPT infants.

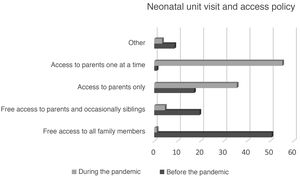

Neonatal unit access policy changes during the pandemic resulted in a decrease in the units that allowed free access to all family members 50.6% to 1.1% (P < .001) and in the units that allowed free access to parents and occasionally siblings from 19.5% to 4.6% (P = .002) (Fig. 1). The hospitals that allowed 24-h access decreased from 93.1% to 82.7% (P = .03). Respondents did not report changes in the time of skin-to-skin contact (90.8%).

In conclusion, the perinatal care of MLPT infants includes practices associated with protective factors that lower neurodevelopmental risk and that promote parent-child bonding in most neonatal units in Spain. These care practices have been introduced due to the growing understanding and interest in the vulnerability of MLPT infants. We found changes in perinatal care practices in response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, with restricted access to the delivery room and, in the case of hospital admission, decreased contact between infants and the family due to limited access to neonatal units, which could create additional emotional stress on parents and health care professionals; it is also likely that the decrease in the frequency of rooming-in, the lack of post-discharge home-based care programmes, the difficulty accessing primary care centres and the decrease in breastfeeding support groups had a negative impact on breastfeeding rates.

A greater effort in improving the specific care of MLPT infants according to the guidelines proposed by the SEN32-36 working group of the SENeo for perinatal care in MLPT infants6 would contribute to making care practices more consistent throughout Spain.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Nadal S, García Reymundo M, Ginovart G, Anquela I, Hurtado JA. Cuidados perinatales del prematuro moderado y tardío en España. Impacto de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;97:69–71.