The most frequent tick-borne diseases in Spain are Mediterranean spotted fever, Lyme disease and tick-borne lymphadenopathy (TIBOLA).1 Interest in these diseases has grown in Spain since the first autochthonous case of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever was diagnosed in 2016.2 Nevertheless, tick bites continue to be an infrequent reason for emergency department visits, which is why general paediatricians are often not familiar with their management. The aim of our study was to analyse whether the implementation of a protocol for tick removal, immediate telephonic consultation with an expert, microbiological testing of the tick and follow-up after discharge in every case achieved a significant improvement in the management of this health problem.

We conducted a retrospective study of 100 tick bite cases in patients that visited the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in the autonomous community of Madrid between March 2011 and July 2018. We then introduced the measures that we have just described and made a prospective analysis of 19 cases managed between April and December of 2019. We assessed improvement in management based on 3 diagnostic and therapeutic goals: tick removal with tweezers in case the patient arrived with the tick, microbiological confirmation of tick-borne disease in patients that start empiric targeted oral antibiotherapy and limitation of the use of targeted oral antibiotherapy against tick-borne diseases in the absence of grounds for suspicion.

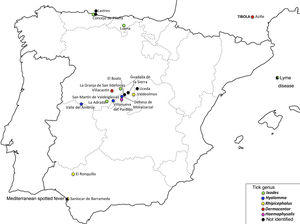

In the period under study, the number of tick bite cases managed per year at the emergency department increased progressively through 2016, when it peaked at 20. Of the total cases, 65.5% (78/119) clustered in the months of April, May and June. Fig. 1 maps the geographical distribution of the 19 tick bite cases included in the prospective analysis, and the microbiological identification of the tick if accomplished.

Table 1 summarises the basic characteristics, diagnosis and management of tick bite cases in the 2 groups under study. We did not find statistically significant differences in the sex distribution, age or presence of fever. Patients that did not receive oral antibiotherapy in the post-intervention period remained asymptomatic 30 days after the tick bite, that is, past the incubation period for the 3 most prevalent tick-borne diseases in Spain.

Clinical characteristics, diagnostic tests and management of tick bite cases in the emergency department.

| Period | March 2011–July 2018 | April 2019–December 2019 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 100 | 19 | |

| F:M ratio | 0.96 | 0.73 | .581a |

| Mean age (SD) | 6.2 years (3.6) | 7.3 years (3.0) | .210b |

| Duration of contact with tick (SD) | Unknown | 60.3h (47.2) | |

| Fever | 12 (12%) | 4 (21.1%) | .289a |

| Location | |||

| Scalp | 36 (36%) | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Face and neck | 29 (29%) | 4 (21.1%) | |

| Upper extremities | 8 (8%) | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Trunk | 18 (18%) | 4 (21.1%) | |

| Lower extremities | 10 (10%) | 1 (5.3%) | |

| Removal method | |||

| Out of hospital | |||

| Manual | 46 (46%) | 3 (15.7%) | |

| Spontaneous | 0 | 1 (5.3%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2%) | 1 (5.3%) | |

| In hospital | |||

| Tweezers | 38 (38%) | 14 (73.7%) | |

| Scalpel or needle | 14 (14%) | 0 | |

| Correct removal method in hospital setting | 38/52 (73.1%) | 14/14 (100%) | .030c |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Serology | 31 (31%) | 6 (31.5%) | .960c |

| Microbiological analysis of the tick | 0 (0%) | 12 (63.2%) | <.001a |

| Conformation of tick-borne disease | 0 (0%) | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Targeted oral antibiotherapy for tick-borne disease | 26 (26%) | 3 (15.7%) | .560a |

| Conformation of tick-borne disease | 0/26 (0%) | 2/3 (66.6%) | .007a |

| Oral antibiotherapy in absence of grounds for suspicion | 10/26 (38.4%) | 0/3 (0%) | .532a |

SD, standard deviation.

In the post-intervention period, ticks removed in the hospital setting were removed with tweezers in 100% (14/14) of children compared to use of a scalpel or needle in 26.9% (14/52) of cases in the pre-intervention period, an improvement that was statistically significant (P=.03).

In the pre-intervention period, of the 26 patients treated with oral antibiotherapy for suspected tick-borne disease, the use of this treatment was justified due to suspicion of TIBOLA in 10 cases (cervical lymphadenitis and/or eschar in the upper body3), suspicion of Mediterranean spotted fever in 4, and suspicion of Lyme disease in 2 (characteristic skin lesion). In all other cases (10/26) no grounds for suspicion of tick-borne disease had been documented. However, in the prospective case series, only 1 patient received treatment for suspected TIBOLA, and the tick genus that may act as a vector (Dermacentor) was only identified in one other patient; 2 more patients received antibiotherapy, one for suspected Lyme disease (confirmed by a positive ELISA followed by a positive western blot) and another for suspected Mediterranean spotted fever (confirmed by IgG seroconversion). Antibiotic prophylaxis was not used in either group of patients. The suspected diagnosis that justified the use of oral antibiotherapy was confirmed in a significantly greater proportion of patients in the post-intervention period (66.7% versus 0%; P=.007).

It is fair to conclude that the management of children with tick bites in the emergency care setting is an area for improvement that requires involvement of an infectious disease specialist and in which the following 3 aspects are important: (1) correct removal of the tick, (2) microbiological testing (including microscopic examination of the tick to identify the species) and (3) the overuse of antibiotic agents due to the low suspicion of tick-borne infectious disease.

Please cite this article as: García-Boyano M, Oliver Olid A, Molina Gutiérrez MÁ, Santana Rojo V, López Hortelano MG. Optimización del manejo de la mordedura de garrapata: estudio prepostintervención. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;94:110–112.