Perampanel (PER) is an antiepileptic drug approved for patients aged more than 12 years with partial and generalised tonic-clonic seizures. At present, the available data on their effectiveness in the management of absence seizures are scarce, and the number of patients aged less than 4 years included in these studies in negligible.1,2 We present the cases of 3 children that developed atypical absence seizures at the time of initiation of PER.

Case 1. Girl aged 3 years with no history of interest with onset at age 2 years of progressive myoclonus epilepsy of unknown aetiology, with impairment predominantly of motor skills, ataxia and dysarthria. The patient did not respond to multiple antiepileptic drugs (valproic acid, levetiracetam, ethosuximide, phenytoin, lacosamide, topiramate, zonisamide, clobazam, piracetam and brivaracetam) or a ketogenic diet. Treatment with PER was initiated, reaching a total dose of 2mg/day, in combination with brivaracetam, clobazam and piracetam. After 1 week she started experiencing frequent atypical absence seizures associated with episodes of progressive atony with a slow drooping of the head and trunk that were documented by video encephalography (VEEG). The patient experienced electroencephalographic resolution of the atypical absence seizures 1 week after discontinuation of PER.

Case 2. Girl aged 3 years and 2 months with Angelman syndrome. The patient presented with psychomotor delay and myoclonic seizures with onset at 12 months, and developed an epileptic encephalopathy electroencephalographic pattern with daily episodes of myoclonus refractory to antiepileptic drugs (levetiracetam, valproic acid and clobazam). Treatment with PER in combination with valproic acid and clobazam was initiated, reaching a maximum daily dose of 4mg/day. The patient exhibited progressive general deterioration with continuous episodes of halts in activity accompanied by repetitive blinking, and VEEG monitoring revealed features of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (continuous atypical absence seizures). After discontinuation of PER, there was a decrease in the absence episodes, with evidence of electrographic improvement.

Case 3. Boy aged 1 year and 7 months with psychomotor delay from the early months of life of unknown aetiology. He had onset of epilepsy at age 6 months, with focal hypomotor seizures and several forms of status epilepticus in the posterior cortex. The epilepsy was refractory to valproic acid, levetiracetam, clobazam, zonisamide, carbamazepine, lacosamide and the ketogenic diet. Treatment with PER was initiated in association with valproic acid, levetiracetam and clobazam. The patient reached a maximum dose of 2mg/day. Perampanel was discontinued after 3 and a half months following evidence in VEEG of nonconvulsive status epilepticus with atypical absence seizures that disappeared after discontinuation of the drug (Fig. 1).

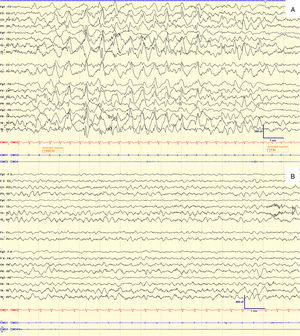

Electroencephalogram of case 3 during treatment with PER (A) and after discontinuation of PER (B).

The top image (A) shows the ictal tracing during one of the episodes of reduced movement and changes in facial expression, associated with continuous mild blinking occurring every 5–10s. The tracings show a slow, high-amplitude spike-wave activity, more or less rhythmical, diffuse and with predominance of the posterior regions pattern, with abrupt onset and end. At this time, the patient was receiving PER at a dose of 2mg/day.

The lower image (B) shows the interictal EEG 2 weeks later, after discontinuation of PER. The tracings reveal adequately organised wake activity, with a tendency towards slowing, without epileptiform abnormalities or asymmetries. There were no atypical absence seizures.

Changes in the concomitant treatments were not made in any of the patients, and none experienced any relevant side effects from these treatments.

We did not find any reports in the literature of cases of development of atypical absence seizures with PER, but the paradoxical worsening of epilepsy induced by antiepileptic drugs is already a well-known complication.3

At present, the literature on the use of PER in the treatment of absence seizures is scarce. French et al.2 included patients with absence seizures, and although they found no evidence that the drug exacerbated these seizures, they did not analyse the efficacy of PER against them.2 Villanueva et al. included 37 patients with absence epilepsy, of who only 7% experienced worsening.4

We believe that certain characteristics of our patients may have contributed to their clinical worsening. One was their age, as the study by Biro et al.5 revealed a greater increase in seizures during treatment with PER in the 2-to-5-year age group. On the other hand, the data on the effectiveness of PER for treatment of atypical absence seizures are scarce. Swiderska et al.6 analysed the efficacy of PER in 4 patients with atypical absence seizures, and none exhibited a reduction in the seizures. Biro et al.5 included 4 patients with atypical absence seizures and found 2 patients that did not respond and 1 that experienced an exacerbation of these seizures.5 Last of all, we think a relevant factor was that our patients had epilepsy refractory to drugs in addition to other unfavourable conditions. For instance, when Villanueva et al.4 compared the outcomes of treatment with PER in patients with myoclonic seizures, they found a higher frequency of improvement compared to other studies that included patients with refractory epilepsy and other unfavourable conditions, such as progressive myoclonic epilepsy.4

The limitations of our study are significant due to its retrospective design and a small sample. However, we believe that contributing information from clinical experience is of great interest for the purpose of starting to profile the characteristics of patients at higher risk of experiencing worsening of specific seizures with PER.

Please cite this article as: Duat Rodríguez A, Cantarín Extremera V, García Fernández M, García Peñas JJ, Ruiz-Falcó Rojas ML. Inducción de crisis de ausencia atípica durante el tratamiento con perampanel. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;91:346–348.