Paediatric post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) is defined as the collection of physical, mental and emotional symptoms that continue to persist after a patient is discharged from the unit. This term applies both to paediatric patients (p-PICS) and to their families (f-PICS).1

Up to 84% of carers of patients admitted to paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) develop post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms, and other disorders, such as anxiety and depression, have also been reported. In parents, having the opportunity to discuss their feelings openly has been described as a protective factor, so early interventions that improve family communication could be helpful in this regard.2,3

Intensive care unit (ICU) diaries are prospective narratives in which health care professionals or family members describe the experiences and feelings of the writer and the patient. Reading these narratives after the ICU stay has been proposed as a means to prevent and treat PICS.4

In the paediatric population, only one ICU diary initiative has been carried out, in the United States, in a group of 20 participants.5 More initiatives should be implemented especially focused on children and their particular vulnerability. Therefore, we present a pilot experience with the introduction of PICU diaries carried out between May 2021 and May 2022 in the PICU of the Hospital 12 de Octubre in Madrid, Spain.

We conducted a prospective descriptive study to assess the feasibility of implementing this initiative and how it was received by the participants.

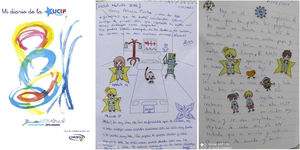

We developed original diaries specifically designed for the paediatric population by a paediatrician and an early childhood education teacher. The pages had a depiction of a patient box for a background, and there were stickers representing the devices and staff most frequently found in a PICU (Fig. 1). The diaries were printed by Ordesa© (Huesca, Spain) free of charge, and the study did not receive any other form of financial support. The inclusion criteria were PICU stay longer than 4 days, recovery from cardiac arrest or septic shock.

During the follow-up, we recruited a total of 24 families, in which the median patient age was 1.3 months (interquartile range [IQR], 0.26–15 months). The inclusion criterion was stay longer than 4 days in 22 cases and septic shock in 2. The most frequent reason for admission was postoperative care following heart surgery (14/24). The median length of stay in the PICU was 15 days (IQR, 5–27).

Entries were chiefly written by parents (24 parents, 114/182 entries), followed in frequency by staff (33 professionals, 57/182 entries), which diverged from the previous literature, in which most entries were written by health care workers. This highlights the importance of involving the family in patient care in a situation in which the role of protecting the minor is taken away from the usual carers; the quality and frequency of parental involvement during the stay in the PICU is a determinant in the capacity to cope with F-PICS post discharge.6

As for the narrative structure of the diary, we found that most entries contained information about the hospital stay (124/309); and there were also frequent messages of encouragements and entries about feelings in the family.

We developed a satisfaction questionnaire that we sent electronically to families after discharge. Fourteen of the 24 participants submitted responses. All families had read the diary, most of them (8/14) between 5 and 10 times. On a scale from 1 to 4, the usefulness of the diary in involving the family in patient care was rated at 3.7 points. In addition, 13 of the 14 respondents considered that it helped discuss the experience of the PICU stay with other family members.

The entries in the open text field provided for families to assess the diary (Table 1) were positive in every case, highlighting how it facilitated sharing the experience with other family members (especially siblings) and that it was a source of emotional support during the stay.

Number and subject of the entries written in the notebooks. Results of the survey of family members.

| Number of entries over total entries. The absolute number of authors is presented in parentheses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Nurses | Doctors | NAs | Patients | Other | Total |

| 114 (24) | 26 (17) | 23 (10) | 8 (6) | 6 (3) | 5 (3 siblings, 2 radiology technicians) | 182 |

| Subjects of the entries | ||||||

| Hospital events | Encouragement messages | Feelings of relatives | Feelings of patients | Out-of-hospital events | Feelings of professionals | Other |

| 124 | 52 | 45 | 45 | 21 | 14 | 8 |

| Family questionnaires (rated over 4 points) | ||||||

| Do you feel the diary was helpful while you/your family member were/was staying in the PICU? | 3.64 | |||||

| Did the diary help you discuss your experience with the PICU stay with your family? | 3.42 | |||||

| The diary helped me during the PICU stay to entertain myself/to feel that I could contribute to the recovery of my child | 3.71 | |||||

| General rating of the diary | 3.78 | |||||

| Open-ended question. Positive-negative perception | ||||||

| Positive. I think it is a way to express what is happening through stickers, and it is actually entertaining for them | ||||||

| Positive. It helps clear your mind as you write about the experience. Later you have good memories of the days you spent there, so traumatic but so necessary | ||||||

| Very positive, although it is an experience nobody wants to have, as family, it served as an outlet for me, to describe a bit what was going on with my daughter. It is wonderful to move forward with this project | ||||||

| Positive. During the stay in the PICU, it served as a distraction and was very entertaining for my child | ||||||

| Positive, as it reminds you of what is good about the PICU | ||||||

| Positive, because it helps you express all that is happening | ||||||

| Positive. It is a beautiful way to remember everything I experienced with my daughter clearly, and at the time I was writing it helped to relieve stress a bit | ||||||

| Positive. Today, my older children can read the diary and have an idea of what was going on with their newborn sister | ||||||

| Positive. It is a way to identify your emotions at a very difficult time | ||||||

| Positive, as we watched his evolution day to day and when we read it we see that he kept improving and it helps us stay positive about his disease | ||||||

| I liked the initiative a lot, at the time I did not have the strength or desire to talk about my experience or share my feelings even with my closest family, and the diary gave an outlet to my feelings. We kept using it until we came back home | ||||||

| I think it’s positive, [the patient’s] siblings could write things down and learn more about [the patient’s] situation | ||||||

| Positive. Our son is a baby and does not understand yet, but it helps us remember, as parents, and we will be able to show it to him and tell him what he went through when he grows up | ||||||

| Positive, because it is a positive and fun way to tell [the patient] what they went through in the ICU, and tell [the patient] with drawings, and so [the patient] has a story and good memories | ||||||

ICU, intensive care unit; NA, nurse assistant.

There are numerous limitations to this study, as it was a pilot experience conducted in a single centre without a control group, and there was no standard reference that would allow comparing the incidence of F-PICS in the “intervention” group.

Nevertheless, our experience suggests that PICU diaries are a feasible initiative that should be contemplated during PICU stays, as they are very well received by families and could help prevent and cope with F-PICS by improving intrafamily communication.

FundingThe diaries were created in-house. They were printed free of charge by Ordesa©, and the study did not receive any other form of financial support.

Previous presentation: The study was presented at the 36th Congress of the Sociedad de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos, June 12–15, 2022, Seville, Spain.