After more than 50 years of experience, newborn screening (NBS) programs represent one of the most significant advancements in public health, particularly in pediatric and neonatal care, benefiting almost 350 000 children annually in Spain. Following the inclusion of congenital hearing loss screening in 2003 and screening for seven congenital diseases by newborn blood spot test in 2014 as part of the population-wide neonatal screening program of the National Health System (NHS), significant advances have been achieved in recent years. This progress is evident in the implementation of screening for critical congenital heart diseases, approved in January 2024 by the National Public Health Commission of the Interterritorial Council of the NHS, as well as screening for congenital diseases through the newborn blood spot test, with the incorporation of new conditions enabled by advances in second-tier testing and emerging scientific evidence. Neonatologists and pediatricians must keep abreast of these developments and where the field is heading, as even more rapid progress may take place with the advent of genomic newborn screening.

Tras más de 50 años de recorrido, los programas de cribado neonatal constituyen uno de los avances más significativos que se han producido en Salud Pública y a nivel asistencial pediátrico y neonatal, beneficiando a casi 350.000 niños/año en España. Tras la inclusión en 2003 del cribado de hipoacusia congénita y en 2014 del cribado de 7 enfermedades congénitas por la prueba del talón en el programa poblacional de cribado neonatal del Sistema Nacional de Salud, se han ido produciendo avances significativos en estos últimos años. Ello se manifiesta con la implementación del cribado de cardiopatías congénitas críticas, aprobado en enero de 2024 en la Comisión Nacional de Salud Pública del Consejo Interterritorial del SNS y en el cribado neonatal de enfermedades congénitas en prueba de talón con la incorporación de nuevas entidades por los avances en la utilización de pruebas de segundo nivel y las evidencias científicas generadas. Los neonatólogos y pediatras en general debemos conocer este nuevo presente, así como hacia donde vamos con un posible avance más rápido con el cribado genómico neonatal.

Population-based newborn screening is an intervention performed for the early detection of congenital disorders that, without apparent symptoms, could cause serious physical, mental or developmental problems and for which early diagnosis and treatment significantly improve outcomes. The aim is to screen 100% of newborns.

Newborn screening is not just testing: it is a program that must focus on the best interests of the child, and the health system must guarantee diagnosis, treatment and follow-up for children identified early through screening. Its widespread use has been one of the great public health and health care achievements in pediatrics as a whole and in neonatology in particular.1

History of newborn screeningGlobal levelIn 1958, what would become the first worldwide newborn screening program for phenylketonuria (PKU) was initiated in the city of Cardiff (United Kingdom) after corroborating that these patients benefited from early initiation of a diet with strict restriction of phenylalanine, which motivated testing for the presence of phenylpyruvic acid in urine in all newborns at 3 weeks post birth. In 1963, the journal Pediatrics published an article on the Guthrie test for PKU screening, demonstrating the usefulness of a blood spot sample in a special filter cardstock for measurement of phenylalanine levels, which set the methodological and theoretical foundations for newborn screening programs.2 Screening for congenital hypothyroidism in the dry blood samples was added in 1970.

In the 1990s, based on the findings of Millington at Duke University in the United States,3 tandem-mass spectrometry (MS/MS) was introduced in newborn screening programs, expanding their scope through the analysis of amino acids and acylcarnitines in the same Guthrie card for the simultaneous screening of several diseases. This is the most powerful tool to emerge in the past 25 years in the field of newborn screening, as this is a method that offers a high versatility, sensitivity and breadth of analysis and has allowed expanded screening through the simultaneous measurement of several metabolites, thereby realizing the ideal of “one sample, one analysis, multiple diagnoses” for a screening test.

SpainIn Spain, newborn screening began in 1968 for PKU, when Professor Federico Mayor Zaragoza launched the program through the University of Granada. In the following years, other centers throughout Spain joined the initiative. In 1978, the Ministry of Health established the Neonatal Early Detection Program for Phenylketonuria and Congenital Hypothyroidism with the publication of Royal Decree 2176/1978 of August 25. Starting in 1979, the National Plan for the Prevention of Retardation was created and implemented in the framework of the Royal Board of Education and Care for the Disabled. With the support of this initiative, several screening laboratories were established, so that by 1980 there were already 10 screening centers (currently, there are 15) and the program covered 25% of newborns. In 1982, the budgeting authority was transferred to regional governments (ACs), which came to be responsible for screening programs.

In the years that followed, there were some advances, such as the introduction of screening tests for additional disorders like congenital adrenal hyperplasia. But, without question, the most important technological advance applied to newborn screening was the introduction by some ACs of MS/MS for the detection of inborn errors of metabolism from year 2000. Galicia was the first autonomous community to introduced expanded newborn screening with MS/MS in June of 2000.4

The Program for the Early Detection of Congenital Hearing Loss in Newborns was approved in 2003 by the Interterritorial Council of the NHS. The goal of the program is to screen all newborns for hearing loss in the first month of life.5,6

Types of newborn screening. Current situationNewborn screening for congenital diseasesThe dried blood spot or heel prick test, formerly referred to as newborn metabolic screening. It is carried out 24 to 72hours post birth after a normal feed by applying drops of blood on a filter paper card, commonly known as “Guthrie card”, that meets the standards established by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (2014/07, Munktell TNF).

The test is designed to detect diseases whose treatment can be initiated within 10-15 days of birth if the detection is based on biochemical markers, as is usually the case, or within 30 days in the case of genetic markers.

How is the sample obtained? The heel prick is the most widely used method to obtain blood samples for newborn screening. The lancet should be inserted in the lateral plantar surface of the heel to avoid damaging nerves, tendons or even cartilage. In addition, the foot should be massaged beforehand to increase local blood flow and sanitized with 2% chlorhexidine aqueous solution or 70° alcohol wiped with a gauze. For the sample to be optimal, the blood spot must contain at least 75μL of blood (approximately 13mm in diameter) and must be allowed to air dry at room temperature away from direct sunlight.

The prick used to collect the screening sample causes pain to the newborn. The analgesic techniques that have been found useful to alleviate this pain are, based on a Cochrane review, breastfeeding or administration of glucose or sucrose solution during the procedure. Other nonpharmacological interventions could enhance these measures, such as eye contact, tactile stimulation, skin-to-skin contact, a pacifier or nonnutritive sucking.7,8

Venipuncture on the back of the hand is another procedure sometimes used in newborns to collect blood samples for screening.9 Although it offers some advantages, like a decreased risk of hemolysis or coagulation, a larger sample volume and possibly less pain, it may give rise to false negatives, so its use is generally not recommended.

In three autonomous communities (ACs) in Spain (Galicia, Murcia, Extremadura) a urine sample is collected at the same time in the same type of filter paper, which is placed in the diaper. It can complement the information obtained from the blood sample and expand the diagnostic spectrum.

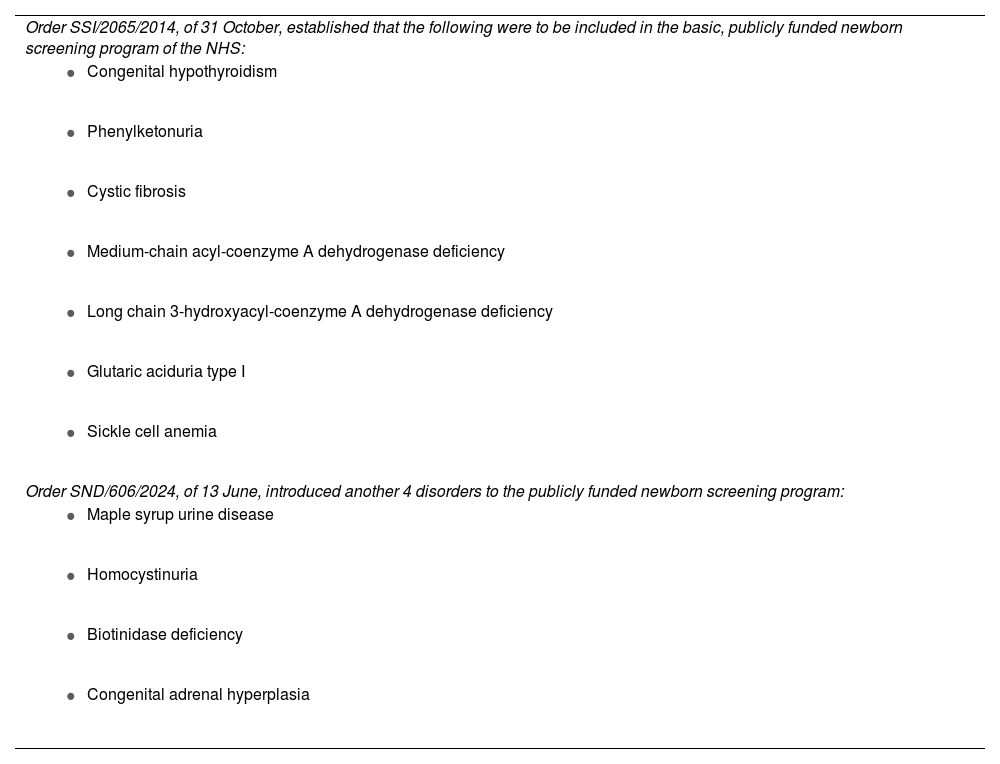

Table 1 presents the diseases currently included in the newborn screening program of the national health system (NHS) and Table 2 the main impact of the diagnosis and the therapeutic interventions available against these diseases. The current situation is one of inequality between ACs, for while five of them (Asturias, Cantabria, Castilla-León, Basque Country, Valencia) screen for the 11 diseases recommended by the NHS, the remaining 12 screen for a greater number of diseases,10–12 with screening covering, for instance, 24 diseases in the first-tier panel in Murcia or 37 in the first-tier panel in Galicia. There is also heterogeneity in newborn screening in Europe and the United States.

Diseases for which neonatal heel prick screening is offered as part of the National Health Service (NHS) universal service portfolio.

| Order SSI/2065/2014, of 31 October, established that the following were to be included in the basic, publicly funded newborn screening program of the NHS: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Order SND/606/2024, of 13 June, introduced another 4 disorders to the publicly funded newborn screening program: |

|

|

|

|

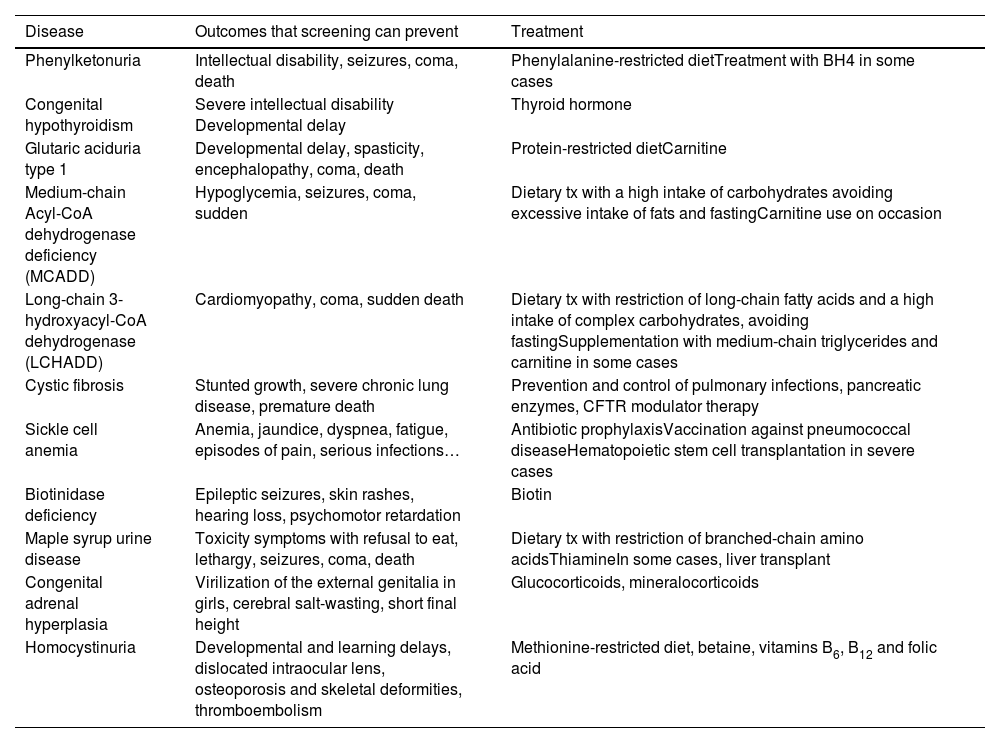

Congenital diseases currently recommended for inclusion in the heel prick test in Spain, outcomes that can be prevented and therapeutic approach.

| Disease | Outcomes that screening can prevent | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Phenylketonuria | Intellectual disability, seizures, coma, death | Phenylalanine-restricted dietTreatment with BH4 in some cases |

| Congenital hypothyroidism | Severe intellectual disability Developmental delay | Thyroid hormone |

| Glutaric aciduria type 1 | Developmental delay, spasticity, encephalopathy, coma, death | Protein-restricted dietCarnitine |

| Medium-chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD) | Hypoglycemia, seizures, coma, sudden | Dietary tx with a high intake of carbohydrates avoiding excessive intake of fats and fastingCarnitine use on occasion |

| Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHADD) | Cardiomyopathy, coma, sudden death | Dietary tx with restriction of long-chain fatty acids and a high intake of complex carbohydrates, avoiding fastingSupplementation with medium-chain triglycerides and carnitine in some cases |

| Cystic fibrosis | Stunted growth, severe chronic lung disease, premature death | Prevention and control of pulmonary infections, pancreatic enzymes, CFTR modulator therapy |

| Sickle cell anemia | Anemia, jaundice, dyspnea, fatigue, episodes of pain, serious infections… | Antibiotic prophylaxisVaccination against pneumococcal diseaseHematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe cases |

| Biotinidase deficiency | Epileptic seizures, skin rashes, hearing loss, psychomotor retardation | Biotin |

| Maple syrup urine disease | Toxicity symptoms with refusal to eat, lethargy, seizures, coma, death | Dietary tx with restriction of branched-chain amino acidsThiamineIn some cases, liver transplant |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | Virilization of the external genitalia in girls, cerebral salt-wasting, short final height | Glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids |

| Homocystinuria | Developmental and learning delays, dislocated intraocular lens, osteoporosis and skeletal deformities, thromboembolism | Methionine-restricted diet, betaine, vitamins B6, B12 and folic acid |

Abbreviations: BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; Tx, treatment.

What technique is used for screening? Currently, screening consists of biochemical tests (metabolites, hormones, proteins) and allows the detection of biomarkers in blood or urine, such as metabolite levels for inborn errors of metabolism (by means of MS/MS), immunoreactive trypsin for cystic fibrosis, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels for congenital hypothyroidism or hemoglobin A for sickle cell anemia. Carriage (genomic) tests are used in first-tier screening for spinal muscular (SMA) and second-tier testing for cystic fibrosis.

Newborn hearing screeningWhat disorders does it cover? Newborn hearing loss, which is usually neurosensory, with 50% to 60% of these cases having a genetic cause.

What technique is used? Objective hearing tests considered adequate for screening include the following:

- 1

The automated auditory brainstem response test evaluates the activity of the auditory pathway from the distal end of the auditory nerve to the midbrain. It has a sensitivity of97% to 100% and a specificity of 86% to 96%. A brief auditory stimulus (clicks or tones) activates the pathway and generates electrical potentials, detectable through electrodes placed on the scalp similar to those used in electroencephalography. The test is carried out when the newborn is at rest with an acoustic stimulation system (headphones) and three electrodes placed on the shoulder, back of the neck and forehead. The headphones issue special sounds, known as clicks, at specific frequencies and volumes, and the electrodes capture the cerebral response to the stimuli. The test takes approximately 3 to 5minutes per ear. The results are obtained automatically and do not require interpretation. The system gives a result of either pass (negative screen) or fail (positive screen). The test can be performed within hours from birth.

- 2

Otoacoustic emission tests are the alternative option, which we consider less adequate, as they do not assess the entire auditory pathway: they assess cochlear, but not retrocochlear, activity, that is, cannot detect auditory neuropathy. They have a specificity of 87% to 99% that is decreased in the first 48hours of life, so performance past this timepoint is recommended. These tests take less time, between 1 and 3minutes.

When should it be performed? The greatest benefit of hearing loss screening is the early detection of moderate to severe congenital hearing loss before age 3 months. Treatment outcomes, in terms of language acquisition and the integration of affected children, depend on how early hearing loss is diagnosed. That is, early rehabilitation improves outcomes both in terms of final hearing levels and communication.13

For this reason, all newborns should undergo hearing screening in their first month of life. The complexity and cost of the screening systems make it strategically desirable to perform the testing in the first days of life, while the child is in the maternity ward, since most children in Spain are born in hospitals. This also allows for the standardization of hearing screening and adequate training of the staff that carries out testing.

In very preterm newborns, screening with either approach should be conducted before 3 months of corrected age.

Screening of critical congenital heart defectsIt was approved by the National Public Health Commission of the Interterritorial Council of the NHS in January 2024. It is performed by means of pulse oximetry, measuring the oxygen saturation of infants born at or after 34 weeks’ gestation in the first 24hours of life.14

What diseases does it include? The purpose of screening is to reduce the risk of delayed diagnosis of critical congenital heart defects, defined as those requiring invasive intervention or resulting in death within 30 days of birth.

What technique is used, and how is screening performed? Pulse oximetry is performed in 2 locations, the right hand and one foot. An oxygen saturation of less than 90% in any of the extremities is interpreted as a positive result, whereas a saturation between 90% and 94% in any location (right hand or either foot) or a difference in saturation greater than 4% is considered inconclusive.

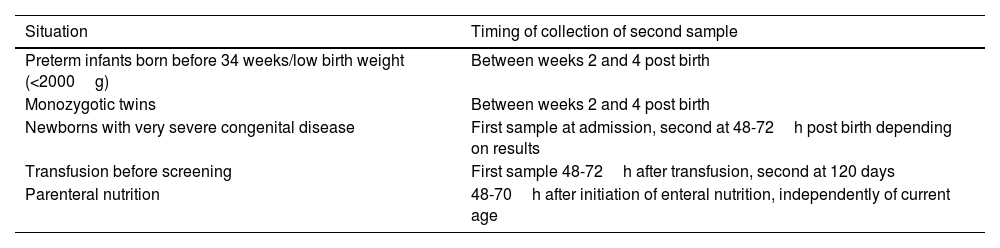

Need for collection of second samples in newborn screening of congenital diseasesWhen screening for congenital diseases in newborns by means of a heel prick test, a single test is sufficient in most cases. However, there are risk situations in which a second test is recommended to minimize the probability of a false negative (Table 3).

Special situations in which a second heel prick sample needs to be collected.

| Situation | Timing of collection of second sample |

|---|---|

| Preterm infants born before 34 weeks/low birth weight (<2000g) | Between weeks 2 and 4 post birth |

| Monozygotic twins | Between weeks 2 and 4 post birth |

| Newborns with very severe congenital disease | First sample at admission, second at 48-72h post birth depending on results |

| Transfusion before screening | First sample 48-72h after transfusion, second at 120 days |

| Parenteral nutrition | 48-70h after initiation of enteral nutrition, independently of current age |

In the case of the hearing screening, if the newborn does not pass the automated auditory brainstem response test, a second test is not necessary and the infant should be referred for diagnostic confirmation with the brainstem auditory evoked response test. However, if otoacoustic emissions are used, especially if screening takes place before 72hours post birth (the external auditory canal is usually filled with detritus the first two days of life), the screening should be repeated at least once before referring the patient for diagnosis.

In the screening for critical congenital heart defects, the recommendation in the case of inconclusive results is to repeat the test only once after 30 to 60minutes and, if the observed values persist, to refer the newborn for immediate evaluation.

New steps in newborn screening in SpainThe Ministry of Health is currently conducting an evaluation to expand the basic, publicly funded screening program to more than 20 diseases. Some of the factors that have contributed to the inclusion of additional conditions are, on one hand, the use of second-tier tests, which improve the efficiency of screening, and, on the other, the growing scientific evidence on the diseases newly included in some programs.

In January 2024, the Public Health Commission of the Interterritorial Council of the NHS approved the inclusion of tyrosinemia type I in the newborn screening program. The framework required to implement it within the fully funded basic health care service portfolio of the NHS is currently being established after the approval from the Committee on Benefits, Insurance and Funding and the Interterritorial Council of the NHS. Additional diseases, such as methylmalonic, propionic and isovaleric acidemias or SMA, among others, are currently being evaluated for possible inclusion in the program.

It is important to keep in mind that today, the technological revolution brought by MS/MS to newborn screening programs, combined with other advances in different serological techniques, capillary electrophoresis and other methods, makes it possible to detect more than 60 diseases in newborns through biochemical markers.15 It is also worth noting that some of the biomarkers or tests used do not offer the desired specificity and give rise to false positives. This has made it necessary to use second-tier tests or markers to minimize the false positive rate. Second-tier tests are performed in the initial dry blood spot sample that yielded abnormal results in the newborn screening, which is the only circumstance under which second-tier tests are used to identify or rule out a disease.16 Only some diseases, such as severe combined immunodeficiencies or SMA, required genetic tests for their detection, although some ACs in Spain and some countries directly use genetic testing for screening of cystic fibrosis. However, the generalized application of next generation sequencing, combined with the reduction in the associated costs, is going to change the landscape of newborn screening.17

If we consider the following:

- •

There are more than 7000 rare diseases and 80% have a genetic basis

- •

The current average delay in the diagnosis of congenital diseases with a genetic etiology is of 6 years

- •

The understanding of the molecular underpinnings of congenital genetic disorders is increasing by the day

- •

The decreasing cost of massive sequencing techniques

- •

The opportunity afforded by molecular testing to provide genetic counseling to families

- •

The increased pace at which new treatments are being developed

We can see the potential for more rapid advances in the field with the implementation of genomic newborn screening, which could also help elucidate the underlying molecular defect in many more diseases. To our knowledge, there are currently 34 groups across the world that are conducting research on genome sequencing as a means to expand newborn screening with the aim of identifying infants with treatable genetic disorders, most of them in the early stages.18–22 Such pilot studies are taking place in the United States, Australia, United Kingdom, Qatar, Greece, France, Germany and Belgium. At the level of the European Union, a multicenter study is currently underway with participation of several countries and coordinated by Italy (Screen4Care).

An innovative pilot study for genomic newborn screening (CRINGENE) to supplement biochemical screening approved by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and supported by European funds is going to be conducted in Spain in 2500 newborns from nine autonomous communities in the 2025-2026 period. Genomic methods will be used for the early detection and treatment of approximately 300 diseases, thus benefitting newborns. This will be an advanced in neonatal care and position Spain as an international leader in the research that is being conducted to open up highly novel and strategic fields.

ConclusionAdvances in technology and metabolomic markers, combined with the growing body of evidence on additional diseases that could be suitable for screening, have been contributing to substantial progress in population-based newborn screening programs in recent years, and the future appears promising with the incorporation of next generation sequencing techniques. All of these developments are of great interest to pediatricians.