Home birth is a controversial issue that raises safety concerns for paediatricians and obstetricians.

Hospital birth was the cornerstone to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality. This reduction in mortality has resulted in considering pregnancy and childbirth as a safe procedure, which, together with a greater social awareness of the need for the humanisation of these processes, have led to an increase in the demand for home birth. Studies from countries such as Australia, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom show that home birth can provide advantages to the mother and the newborn. It needs to be provided with sufficient material means, and should be attended by trained and accredited professionals, and needs to be perfectly coordinated with the hospital obstetrics and neonatology units, in order to guarantee its safety. Therefore, in our environment, there are no safety data or sufficient scientific evidence to support home births at present.

El parto extrahospitalario es un tema controvertido que genera dudas a obstetras y pediatras sobre su seguridad.

El nacimiento hospitalario fue la pieza clave en la reducción de la mortalidad materna y neonatal. Esta reducción en la mortalidad ha derivado en considerar el embarazo y el parto como fenómenos seguros, lo que unido a una mayor conciencia social de la necesidad de humanización de estos procesos, ha conducido a un aumento en la demanda del parto domiciliario. Estudios en países como Australia, Países Bajos y Reino Unido muestran que el parto en casa puede aportar ventajas para la madre y el recién nacido, pero es necesario que se dote de los suficientes medios materiales, que sea atendido por profesionales formados y acreditados, y que se encuentre perfectamente coordinado con las unidades de obstetricia y neonatología hospitalarias, para poder garantizar su seguridad. En nuestro medio, no hay suficientes datos de seguridad ni evidencia científica que avalen el parto domiciliario en la actualidad.

Going back in history, most births took place at home or in the community.1 Hospital birth is a relatively recent phenomenon that became established in most developed countries throughout the 20th century.2 In the late 1940s, the development of antibiotics, blood transfusions and safe anaesthesia led to a decrease in maternal mortality. In Spain, childbirth moved from the home to the hospital setting in the 1970s as public health care coverage became universal.3 Thus, institutional births were the cornerstone for a reduction in maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide through the admission to hospital of pregnant women on going into labour, which allows strict monitoring of maternal and foetal wellbeing, reduces the risk of infection and guarantees medical intervention if the need arises.

Hospital-based delivery in recent years has resulted in a medicalization and denaturalization of childbirth, which, combined with the conception that it is a safe process that has emerged in our society, has prompted a resurgence in the home birth alternative.1 In December 2014, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published an update to its guideline for intrapartum care that sparked considerable debate. This guideline stated that birth at home on in a midwifery-led unit (freestanding or alongside) was suitable for low-risk multiparous women because the rate of interventions is lower and the outcome for the baby is no different compared with a hospital-based obstetric unit. In the case of low-risk nulliparous women, it stated that birth at home or in an obstetric unit are equally appropriate, with no difference in baby outcomes, although home birth in this group of mothers is associated with an increase (of approximately 4‰) in adverse events in the newborn, most frequently hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) and meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS). The guideline emphasises that it is important to ensure that all women that choose to give birth outside the hospital have rapid and safe access to a hospital-based obstetrics unit in the event of medical complications.4,5

In Spain, the Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (Spanish Socieety of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, SEGO) and the Federación de Asociaciones de Matronas de España (Federation of Spanish Midwife Associations, FAME) have recommended and advocated for the development of more humane models of care during labour and delivery to bring them closer to the natural physiological process of birth while continuing to ensure the safety of the mother and newborn.3 In 2010, the Colegio Oficial de Enfermería (Official Board of Nursing) of Barcelona published a guideline for care delivery in home births6 that was later updated in 2018.7 This guideline was developed for midwives that attend home births so that they can provide adequate care. The guideline reported that current evidence showed that morbidity and mortality outcomes in both mothers and newborns, user satisfaction and the benefit-cost ratio were good in countries where home births were an option offered within the public health system. These good outcomes are directly correlated to the coordination between different levels of care, facilitating the transport of pregnant women and newborns to the hospital. In Spain, there is no officially established level of care coordination pathway facilitating transfer from the home to the hospital, an important aspect to be considered by future parents and health care professionals when choosing a home birth.7

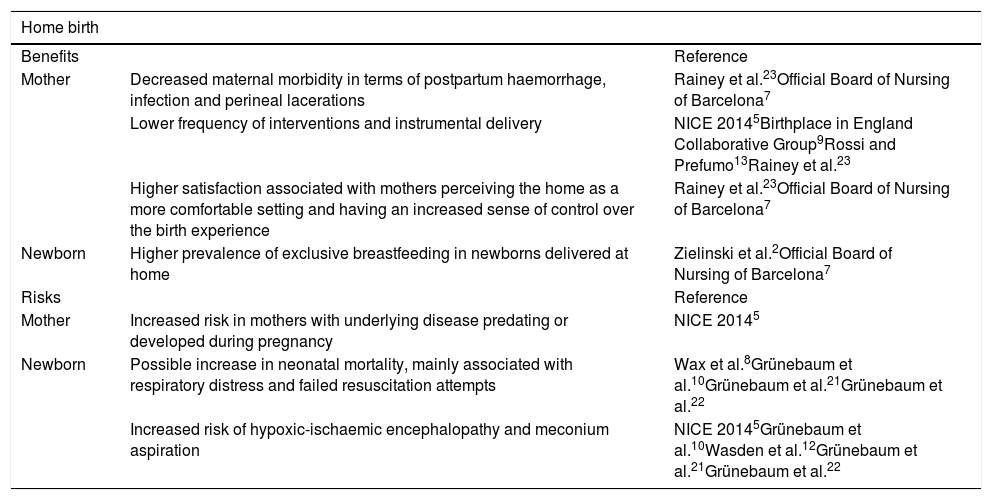

Scientific evidence from the past 10 years on the subject of home and hospital births (Table 1)A meta-analysis published in 2010 by Wax et al. found that the overall neonatal mortality rate was nearly double in planned home births compared to planned hospital births. The reduction in medical interventions was associated with an increased risk of neonatal mortality. This meta-analysis, which did not include information on the assessment of the quality of the included studies, has been criticised for its suboptimal methodology (Table 1).8

Benefits and risks of home birth.

| Home birth | ||

|---|---|---|

| Benefits | Reference | |

| Mother | Decreased maternal morbidity in terms of postpartum haemorrhage, infection and perineal lacerations | Rainey et al.23Official Board of Nursing of Barcelona7 |

| Lower frequency of interventions and instrumental delivery | NICE 20145Birthplace in England Collaborative Group9Rossi and Prefumo13Rainey et al.23 | |

| Higher satisfaction associated with mothers perceiving the home as a more comfortable setting and having an increased sense of control over the birth experience | Rainey et al.23Official Board of Nursing of Barcelona7 | |

| Newborn | Higher prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in newborns delivered at home | Zielinski et al.2Official Board of Nursing of Barcelona7 |

| Risks | Reference | |

| Mother | Increased risk in mothers with underlying disease predating or developed during pregnancy | NICE 20145 |

| Newborn | Possible increase in neonatal mortality, mainly associated with respiratory distress and failed resuscitation attempts | Wax et al.8Grünebaum et al.10Grünebaum et al.21Grünebaum et al.22 |

| Increased risk of hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy and meconium aspiration | NICE 20145Grünebaum et al.10Wasden et al.12Grünebaum et al.21Grünebaum et al.22 | |

In 2011, a large prospective cohort study conducted in the United Kingdom found that women with low-risk pregnancies that gave birth at home or in midwifery units were more likely to have vaginal deliveries with a lower frequency of medical interventions compared to women who gave birth in the obstetrics unit setting. Transfers to hospital from non-obstetric unit settings (home, midwifery unit) were more frequent for nulliparous women (36%-45%) compared to multiparous women (9%-13%). The incidence of adverse perinatal events (stillbirth after start of care in labour, HIE, MAS, brachial plexus injury, fractured humerus, or fractured clavicle) in healthy women with low-risk pregnancies was low in every childbirth setting. However, the risk was higher in home births compared to hospital births (odds ratio [OR], 1.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–2.52). The analysis by parity group did not detect differences in adverse perinatal outcomes in healthy multiparous women with low-risk pregnancies. However, when it came to low-risk nulliparous women, the odds of adverse perinatal outcomes were higher in the home birth group compared to the hospital obstetrics unit setting (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.59–4.92).9

In 2014, Grünebaum et al. published a study conducted in the United States in the 2006–2009 period that assessed early and total neonatal mortality in term newborns with a cephalic presentation, product of a singleton pregnancy and without congenital malformations comparing those whose birth were attended by midwives and doctors in hospitals and those delivered out of hospital by midwives and in some cases by non-health care professionals in emergency situations. The study found that home birth was associated with a nearly 4-fold increase in total neonatal mortality (1.26‰ vs 0.32‰ of births; P < .001) and a nearly 7-fold increase in early neonatal mortality (0.93‰ vs 0.14‰; P < .001) compared to hospital birth. In the subset of nulliparous mothers, the total neonatal mortality was nearly 7 times greater (2.19‰ vs 0.33‰; P < .001) and the early neonatal mortality was nearly 14 times greater (1.82‰ vs 0.13‰; P < .001). In short, this study found a significant increase in total and early neonatal mortality associated with home birth. Home birth was also associated to increases in other adverse neonatal outcomes, such as an Apgar score of 0 at 5 min, convulsive seizures and HIE. The authors noted that the comparability with studies on home birth outside the United States, such as Australia, the Netherlands or the United Kingdom, is limited since home birth in these countries is integrated in the health care system, which is not the case in the United States. Thus, they consider that obstetricians in the United States should advise against the option of giving birth at home.10

In 2015, a study in the Netherlands compared planned home births and hospital births and did not find an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes in planned home births of women with low-risk pregnancies. The authors specified that these results could only be extrapolated to home births in countries where this birth option is fully integrated in the health care system.11

Another case-control study conducted in 2017 in New York City analysed the association between home birth and HIE. Newborns with HIE that required cooling were 16.9 times more likely to have been born out of hospital (whether the setting had or not been planned) compared to newborns without HIE (95% CI, 1.9–153.8). Newborns with HIE were 21 times more likely to have been delivered in a planned home birth compared to newborns without HIE (95% CI, 1.7–256.4). Thus, birth out of hospital, whether planned or not, was more frequent in newborns that underwent cooling for management of HIE. One of the limitations of this study was the small sample size, which resulted in very broad confidence intervals.12

In 2018, a systematic review with meta-analysis conducted by Rossi and Prefumo, did not find differences in the risk of perinatal birth between planned home births and planned hospital births. Transfer to a hospital occurred in 10% of home births and was performed during delivery in 82.2% of cases and post partum in 17.7%. In 43% of cases, the indication for transfer involved the mother and in 57% the foetus or newborn. The articles included in the analysis did not compare maternal and neonatal outcomes of caesarean deliveries performed after transfer to hospital versus caesarean deliveries in mothers that were giving birth in hospital from the outset. Several complications that cannot be anticipated, such as foetal distress, dystocia, placental abruption and others, may develop independently of the planned place of birth and the level of risk of the pregnancy and require prompt intervention, and therefore the hospital setting is much safer than the home when these complications arise. The authors concluded that given the lack of data on maternal and neonatal morbidity after home birth and the limitations of the current literature, the safety of home birth remained in question.13

Another systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2018 with a strict selection of high-quality studies that analysed outcomes in women with low-risk pregnancies in high-income countries concluded that place of birth seemed to have an insignificant impact on the incidence of adverse perinatal events. Most studies included in the analysis had limited statistical power to detect differences in rare outcomes, as the low perinatal mortality in developed countries require combining data from different studies to obtain sufficiently large samples of home births to get significant results.14

In 2019, Hutton et al. published a very thorough systematic review with meta-analysis conducted to determine whether the risk of fetal or neonatal loss differs among low-risk women who begin labour intending to give birth at home compared to low-risk women intending to give birth in hospital. In nulliparous women intending a home birth in settings where midwives attending home birth are well integrated in health services, the OR of perinatal or neonatal mortality compared to those intending hospital birth was 1.07 (95% CI, 0.70–1.65) and in less integrated settings 3.17 (95% CI, 0.73–13.76). The authors concluded that in low-risk women, the risk of perinatal or neonatal mortality or morbidity did not increase in case of a planned home birth as opposed to a planned hospital birth. It should be taken into account that most of the studies of highest quality came from settings where the midwives that attended home births were well integrated in the health care system. The authors acknowledged that this was a source of bias due to the exclusion of studies in less integrated settings in which the likelihood of adverse outcomes is probably higher. They also noted that while they did not find differences between intended home births versus intended hospital births, in less well-integrated settings there was a trend towards favouring hospital births that could be of interest.15

Current situation of home birth in different countriesHome birth is well integrated in the health care systems of some countries, such as Canada, United Kingdom, Iceland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and the state of Washington in the United States.16

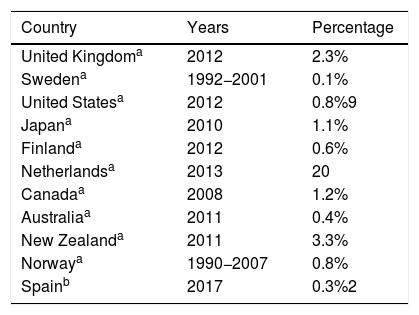

At present, the proportion of home births in Western countries range from 0.1% in Sweden to 20% in the Netherlands (Table 2).17 In Spain, based on data of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (National Institute of Statistics) a total of 1273 births occurred at home in 2017, amounting to 0.32% of all births.18

Comparison of percentages of home births by country.

In the United Kingdom, births outside the hospital are nearly always attended by experienced midwives in the framework of the national health system with established referral pathways to obstetric units if complications occur. Therefore, the findings of studies conducted in the United Kingdom cannot be generalised to countries with a different model of care delivery for home births.9

In the NetherlandsIn the Netherlands, starting at 37 weeks’ gestation, mothers with low-risk pregnancies can choose between giving birth at home, in a midwife-led birthing centre or at hospital. Most midwives in the country form group practices. When complications arise, the woman is transferred to a hospital. There is a multidisciplinary guideline developed through consensus of all health professionals involved in perinatal care on the indications for transfer.19

In AustraliaIn Australia, relatively few women choose to give birth at home (in 2013, home births amounted to 0.3% of all deliveries). Publicly funded home births have emerged as a model of maternity care in Australia. Women also have the option of having a home birth managed by one or more midwives in private practice.20

In the United StatesThe option of out-of-hospital birth is not well integrated in the health care system. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) state that hospital births are safer compared to home births given the increased risk of perinatal adverse events found in population-based studies. These 2 professional associations published a statement on planned home birth that provided recommendations on when to consider this option, detailing strict criteria for selection of appropriate candidates21 associated with lower perinatal mortality rates. These criteria include:

- -

Absence of pre-existing maternal disease

- -

Absence of significant disease with onset in pregnancy.

- -

Singleton pregnancy.

- -

Cephalic presentation.

- -

Gestational age greater than 36 weeks and less than 41 weeks.

- -

Spontaneous or induced labour.

- -

Women not referred from another hospital.

In cases in which these criteria are met, in order to reduce perinatal mortality and achieve favourable outcomes of home birth, it is essential that the birth be attended by a certified midwife trained in neonatal resuscitation practicing within a regulated and integrated health care system and with access, if needed, to a medical transport team for safe transfer of the mother and newborn to a nearby hospital within an optimal time frame.

Absolute contraindications include a previous history of caesarean delivery, abnormal foetal presentation and multiple pregnancy. In these cases, both doctors and midwives are bound by professional ethics to strongly recommend a hospital delivery and refuse requests to attend home births under these circumstances.21

To these contraindications we must add those identified in a study recently published by Grünebaum et al, who reported an increase in neonatal mortality associated with breech presentation, nulliparous status and gestational age equal to or greater than 41 weeks. This risk seems to increase when these factors are combined with maternal age greater than 35 years.22

Current recommendations proposed for SpainThe minimum criteria for home birth are delivery by a skilled provider and availability of immediate care in the event of complications. The safety of home births depends on multiple factors, as the availability of resources for home birth varies widely based on location, even within each country.

There are several important determinants of poor perinatal outcomes in home births, including the quality of intrapartum foetal monitoring, the experience of the attending professionals, the access to neonatal care and above all the response to the development of complications during home birth, with the time elapsed to the decision to seek care and to arrival to a facility offering adequate perinatal being the greatest contributors to this increase in risk.1

Professionals that attend homebirths must have sufficient knowledge and experience not only to attend the birth, but also to guide the appropriate selection of candidates to this childbirth modality and to detect early signs of nonreassuring foetal status.3,22 In this instances, adequate and early transport of these women should be guaranteed, as transfer in the event of acute and sudden events such as cord prolapse, placental abruption and shoulder dystocia may not take place fast enough if these potential complications are not anticipated, which would result in an increased incidence of HIE and other adverse perinatal outcomes.1

The establishment of standardised guidelines detailing the criteria for eligibility and the risk factors at play in home birth is an essential component of safety in this childbirth option.2 While the evidence on the neonatal outcomes of home birth is largely inconclusive,23 it seems clear that when there are established guidelines and systems for transfer to hospital there is no increased risk associated with home birth in women with low-risk pregnancies.2

In Spain, home birth would require fulfilment of all of these criteria3:

- -

Selection of candidates based on the absence of risk criteria during pregnancy.

- -

Full understanding of future parents, who must be informed appropriately, of what a home birth entails.

- -

Availability of adequate resources for the home setting in addition to support by close family.

- -

Existence of a care network of health providers highly qualified to attend births with the support of a medical transport system that would allow urgent transfer to a hospital.

Given the current structure of the health care system in Spain, home birth cannot be recommended in our country. In the context of how health care should evolve in the future, we are now at a perfect juncture in which to take steps toward a model of childbirth better fitting the physiological process that it actually is. Our health care system must provide settings that are respectful of women during pregnancy and labour and avoid excessive medicalization of childbirth while optimizing the safety of the mother and the child. Data from other countries such as Australia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom evince that birth outside the hospital can offer significant benefits to the mother and newborn, and in the future, this option could also be available in Spain, especially to multiparous women. However, this would require allocation of adequate material resources, management of childbirth by properly trained and accredited providers, and seamless coordination with hospital-based obstetrics and neonatology units.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Redondo MD, Cernada M, Boix H, Fernández MGE, González-Pacheco N, Martín A et al. Parto domiciliario: un fenómeno creciente con potenciales riesgos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:266.