Managing the impact of the death of paediatric patients is a critical challenge for resident physicians and paediatricians, who experience the emotional repercussions of the death of young patients and its impact on families. Some of the possible strategies to address this challenge would be the delivery of structured comprehensive training in palliative care and bereavement management from the early stages of medical education, pursuing an institutional culture that supports the emotional wellbeing of health care professionals, promoting multidisciplinary collaboration in paediatric end-of-life care and fostering self-care and self-compassion in healthcare professionals.1 Previous publications have proposed various structured interventions to facilitate the processing of loss and grief, improve coping strategies and, ultimately, strengthen the emotional resilience of professionals working in clinical settings.2

“Death rounds,” one of the tools available to healthcare professionals, are based on established grief and bereavement counselling principles and provide a specific opportunity for participants to express, share and process grief resulting from their clinical work.3–5 We developed an interventional study with the aim of exploring this tool for improvement of care delivery by paediatric professionals, processing the impact and emotional repercussions of end-of-life experiences shared with children and their families and addressing challenges and deficits in managing these situations.

We conducted a qualitative interventional study in the department of paediatrics of a tertiary care hospital that includes a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and offers residency training. With the collaboration of a mental health specialist with expertise on psychotherapy and grief, we designed and held structured meetings for healthcare professionals to address end-of-life care for paediatric patients and bereavement care for families. During these meetings, which lasted approximately 2 hours, attendees discussed aspects related to counselling and support skills using the same clinical scenario as a guiding thread for educational purposes, a case narrative based on the death of a real patient from a subjective and emotional perspective. The narrative, written by the organisers, highlighted essential aspects about the moment of death, including the provision of support by health care professionals and their own self-care and management of emotions, followed by a discussion in which participants shared their opinions and experiences. We invited groups of 4–6 professionals to participate on a voluntary basis, with different participants in each meeting, and meetings were held monthly after being announced in the department.

To assess the impact of these meetings, we analysed the responses to two questionnaires. The first one focused on the previous experience and knowledge of participants in relation to end-of-life care, and the second evaluated the perceived knowledge and skills acquired through the meeting and their perceived usefulness in the participant’s practice. The questionnaires were administered through the Google Forms platform.

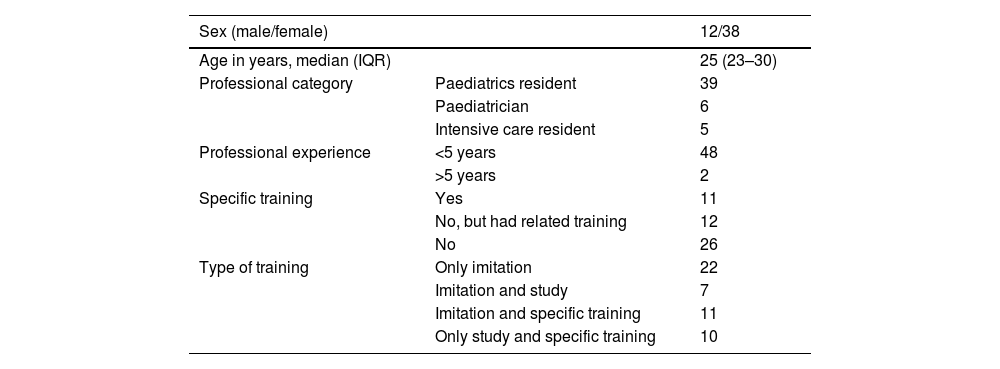

During the study period, between 2018 and 2019, a total of 50 physicians divided in groups participated in at least one of the nine meetings held. Table 1 summarises the demographic and professional characteristics of the participants. Eighty percent (n = 40) reported having developed skills in end-of-life care through imitation of other professionals (which was the sole means of training in 44%) and only a minority (n = 10) reported learning through reading and studying. In the questionnaire prior to training, nearly all participants (92%) expressed a need for specific training in grief/bereavement, ethics, delivering bad news and the management of challenging situations.

Characteristics and previous experience of training participants.

| Sex (male/female) | 12/38 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 25 (23–30) | |

| Professional category | Paediatrics resident | 39 |

| Paediatrician | 6 | |

| Intensive care resident | 5 | |

| Professional experience | <5 years | 48 |

| >5 years | 2 | |

| Specific training | Yes | 11 |

| No, but had related training | 12 | |

| No | 26 | |

| Type of training | Only imitation | 22 |

| Imitation and study | 7 | |

| Imitation and specific training | 11 | |

| Only study and specific training | 10 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Out of the 50 participants, 80% (n = 40) evaluated the experience and the knowledge they had acquired in the training through a second questionnaire. Of this subset, 77% (31) reported and demonstrated the acquisition of new knowledge and support skills and 88% expressed increased confidence in facing the death of a patient. When it came to self-care, 95% of professionals rated the received training as useful or very useful, highlighting aspects like teamwork, sharing feelings and experiences and introspection. Most of them (92%) considered the duration and number of participants adequate. All participants that completed the post-intervention questionnaire agreed on attending additional sessions and establishing a continuing education programme on the subject.

As a novel approach, the strategy presented here was based on the use of the case narrative for medical education, which, combined with other training approaches, proved more effective than any of them in isolation,6 underscoring the importance of the message and its alignment with the target audience and the objectives of the training. During the intervention, the physicians that participated requested further training on end-of-life care and related coping and bereavement management skills. Death rounds emerged as a useful tool to address and process these aspects and were rated very positively by the same professionals that demanded training. This and other strategies can help prepare them to face the emotional and professional challenges associated with death and contribute to reducing burnout among paediatricians and medical residents.

FundingManuel Gijón Mediavilla receives funding for his research through a Río Hortega grant/contract of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, a public entity for health research promotion in Spain.

We thank all the physicians that participated in the death rounds and contributed to this work with their responses regarding their personal experience and self-efficacy.