According to the Global Pediatric Education Consortium (GPEC), paediatricians need to acquire and maintain a set of competencies in their daily practice. Continuum, the online training platform of the Spanish Association of Pediatrics, has developed training activities to explore and achieve these competencies.

MethodsCross-sectional study of the training activities delivered on Continuum over eleven years and the competencies assigned to each of them. The period 2013–2024 was analysed through a descriptive analysis of competency coverage.

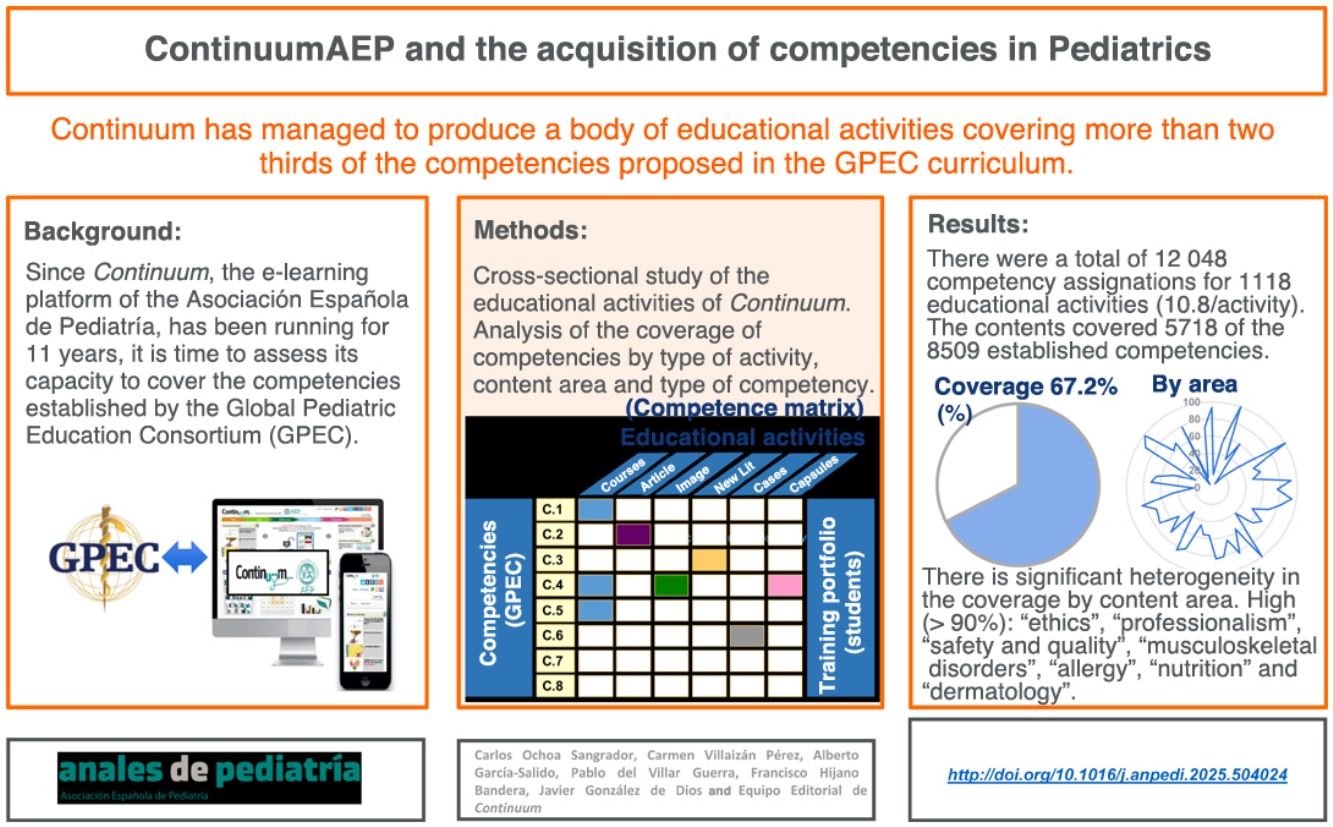

ResultsA total of 12 048 GPEC competencies were assigned to 1118 training activities, with an average of 10.8 competencies per activity. Of the 8509 competencies available in the Continuum competency matrix, 5718 were addressed at least once. This amounts to 67.2% of the total (95% confidence interval [CI], 66.2 %–68.2%). Each competency was assigned an average of 2.11 times (95% CI, 2.07–2.15). There was considerable heterogeneity in the coverage by area of competence. We ought to highlight the high coverage (>90%) for the areas of “Professionalism”, “Patient Safety and Quality Improvement”, “Musculoskeletal Disorders”, “Allergy”, “Dermatology” and “Nutrition” and the low coverage (<10%) for “Self-Leadership and Practice Management” and “Gynecology”.

ConclusionsIn the period under study, the Continuum platform enabled the attainment of more than two-thirds of the competencies required for pediatric practice as established by the GPEC. We identified asymmetries between knowledge areas. These should be considered to prioritize access to underrepresented competencies.

Según el Consorcio Global de Educación Pediátrica (GPEC), los pediatras necesitan adquirir y mantener en su práctica diaria una serie de competencias. Continuum, la plataforma de formación en línea de la Asociación Española de Pediatría, ha desarrollado actividades formativas para explorar y obtener estas competencias.

MétodosEstudio transversal de las actividades docentes impartidas en Continuum durante once años y las competencias asignadas a cada una de ellas. Se analiza el periodo 2013–2024 mediante un análisis descriptivo de la cobertura de competencias.

ResultadosSe asignaron 12 048 competencias del GPEC a 1118 actividades docentes, con una media de 10,8 competencias por actividad. De las 8509 competencias disponibles en la matriz de competencias de Continuum, 5718 fueron abordadas al menos una vez. Esto representa el 67,2% del total (intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95] 66,2 a 68,2%). Cada competencia se asignó en promedio 2,11 veces (IC95: 2,07 a 2,15). Se observó una importante heterogeneidad en la cobertura por áreas. Destacan la alta cobertura (>90%) de las áreas de “Ética en la práctica clínica”, “Profesionalismo”, “Seguridad del paciente y mejora de la calidad”, “Trastornos musculoesqueléticos”, “Alergia”, “Dermatología” y “Nutrición” y la baja cobertura (<10%) de “Autoliderazgo y gestión de la consulta” y “Ginecología”.

ConclusionesEn el periodo analizado la plataforma Continuum ha permitido obtener más de dos tercios de las competencias necesarias para el ejercicio de la pediatría según GPEC. Se objetivan asimetrías entre áreas de conocimiento. Estas deben ser consideradas para priorizar el acceso a las competencias subexpuestas.

Competency-based education (CBE) is an educational approach based on the application of specific knowledge, skills and attitudes, replacing traditional education based on the delivery of theoretical contents. This is a student-centered approach that places the responsibility of learning on the students, who are required to demonstrate their ability to perform and apply competencies successfully.1,2

Remote learning, facilitated by emerging technologies, is an efficient modality that students can adapt to their own needs.3 In 2013, the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) launched Continuum, an e-learning platform based on CBE. It hosts numerous educational activities designed to develop the competencies (knowledge, skills and attitudes) that pediatricians need in their daily practice. The available contents are structured into various activities (“Training Courses”, “New in the Literature”, “Highlighted Articles”, “Image of the Week”, “Interactive Clinical Cases”, “Learning Capsules”, “Tools”). They are articulated as educational modules developed to cover a predefine spectrum of skills that, together, have allowed the development of a matrix or framework underpinning the educational structure of Continuum.

The Continuum competency matrix was developed based on the collection of documents published by the Global Pediatrics Education Consortium (GPEC).4 This consortium is composed of leaders of 20 national, regional or international organizations devoted to education, training and accreditation in the field of pediatrics. At the same time, it assesses their efficacy with the aim of guaranteeing high-quality learning at the global level. The Continuum competency matrix is an original and standalone database. It holds more than eight thousand elements assigned to a hierarchical coding system to facilitate the management of the competencies involved in each learning activity. This design helps avoid the confusion and aimless rambling that can occur when attention is focused on process without first defining a clear destination or outcome.5

In this original article, we present and describe the CPEC pediatric competencies on which training and education is offered through the Continuum e-learning platform since its inception. The aim was to estimate the coverage of the GPEC curriculum overall and by type of activity and knowledge area. We also sought to describe the profile of the platform users and the rate of engagement and completion for the offered activities.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional and descriptive study of the training activities and competencies offered and delivered through the Continuum platform in the 2011–2024 period. A full description of the platform is available in previous publications.6–8

Study variables- •

Competencies included in the syllabus of the GPEC: included in a database in which each of them is identified through a structured alphanumeric code that refers to distinct areas (core abilities and behaviors; core skills; core knowledge and patient care syllabus), subareas (organ- and body system-based issues; acute, critical and emergency care; palliative, surgery, rehabilitation and sports medicine; developmental issues; adolescence and related issues; issues of abuse; community and preventive issues) and type of competency (history, physical examination, diagnosis, management plan). “Core abilities and behaviors” encompasses the general competencies required for the practice of medicine and pediatrics, while “core skills” encompasses common procedures in pediatric care applicable to different specialties. The database is available through the “Matriz de Competencias” (Competency matrix) page of the Continuum platform.9

- •

Training activities in the platform; we collected their names and characteristics:

- -

Image of the Week (Imagen de la Semana): published weekly. Images related to common diseases that are encountered frequently in clinical practice to expand the visual inventory of pediatricians.

- -

Interactive clinical cases (Casos Clínicos Interactivos): published every two weeks. A real-world clinical case in primary care and in hospital-based care is presented to promote clinical reasoning skills, with particular emphasis on differential diagnosis and the selection of diagnostic tests.

- -

New in the literature (Novedades Bibliográficas): published every two weeks. This section presents a recently published article to offer a review of the studies offering the most ground-breaking findings or that can be particularly significant due to the clinical relevance of their results.

- -

Highlighted articles (Artículos Destacados): published twice a month. The entry provides a link to an article published by one of the leading Spanish pediatric journals (after obtaining the journal’s authorization).

- -

Learning capsules (Píldoras Formativas): no set publication schedule. Brief activities that promote self-learning on very specific subjects.

- -

Training courses (Cursos de formación): no set publication schedule. Predominantly developed by the different societies and committees affiliated to the AEP.

- -

Other available educational contents: “Preparing my rotation in…” (Preparo mi rotación por), “Tools for clinical practice” (Herramientas para la consulta) and “Library” (Biblioteca).

- -

- •

Assigned competencies: before developing the training activities, the authors receive a list of GPEC competencies related to the topic at hand. Each developed learning activity is assigned an alphanumeric code for its identification. After completing each activity, the editorial board of Continuum designates the competencies that were actually covered in it. When the competency is not one of the competencies outlined in the GPEC framework, new competencies are defined and designated. The number of competencies assigned to each activity depends on its type and contents. Students that complete a training or course must pass an assessment test (with at least 70% of correct answers out of a total of 20–30 questions with four possible answer choices, of which only one is correct), with a limited duration (two minutes per question) and two opportunities for passing. The quality of the activity is assessed by means of a quantitative satisfaction questionnaire provided to the students for its completion.

Continuum activities are presented in reverse chronological order. The matrix allows the user to identify the competencies and check the activities that the platform offers to acquire them.

Once the student passes the final assessment for an activity, this activity and the acquired competencies are added to the student’s training portfolio. Users can check which activities they have completed successfully at any time and browse their e-portfolio to determine which competencies they have acquired in each area and which remain to be acquired.

Statistical analysisWe conducted a descriptive analysis of the completed activities, the associated competencies and the participating students. We analyzed the coverage of competencies by area, subarea ad type of competencies for the different types of activity. We estimated proportions for qualitative variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables. We calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the main estimates.

ResultsDescription of activities, authors and usersA total of 1118 activities were offered during the study period. The distribution by type of activity was: training course, 45; new in the literature, 211; images of the week, 469; interactive clinical scenario, 214; highlighted articles, 168; learning capsules, 11. These activities were developed by 2351 authors. Continuum also offered links to 2080 documents, 173 tools and 8 modules of “I prepare my rotation in…”, which are not included in the platform’s competency database.

A total of 22 342 students were registered in the platform, of who only 9936 were members of the AEP (44.4%). In 2024, a total of 2396 students signed up for courses, of who 1287 (53.71%) were residents. A median of 317 students registered for each course (Q1, 233; Q3, 454); 80% completed all the modules, out of who 99% passed the assessment test upon completion.

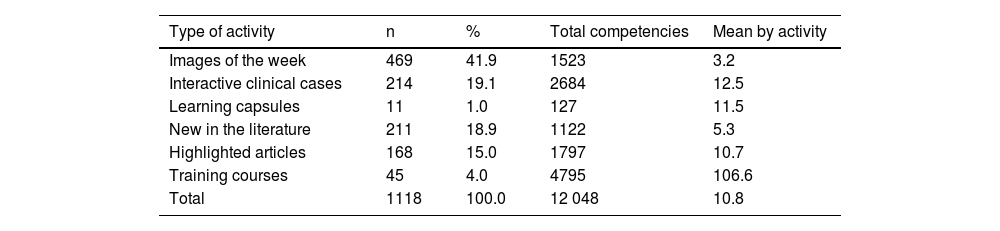

A total of 12 048 competencies were assigned to the activities offered in the first eleven years, with a mean of 10.8 competencies per activity. Table 1 presents the results of the analysis of the competencies by type of activity.

Assigned competencies by type of activity.

| Type of activity | n | % | Total competencies | Mean by activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Images of the week | 469 | 41.9 | 1523 | 3.2 |

| Interactive clinical cases | 214 | 19.1 | 2684 | 12.5 |

| Learning capsules | 11 | 1.0 | 127 | 11.5 |

| New in the literature | 211 | 18.9 | 1122 | 5.3 |

| Highlighted articles | 168 | 15.0 | 1797 | 10.7 |

| Training courses | 45 | 4.0 | 4795 | 106.6 |

| Total | 1118 | 100.0 | 12 048 | 10.8 |

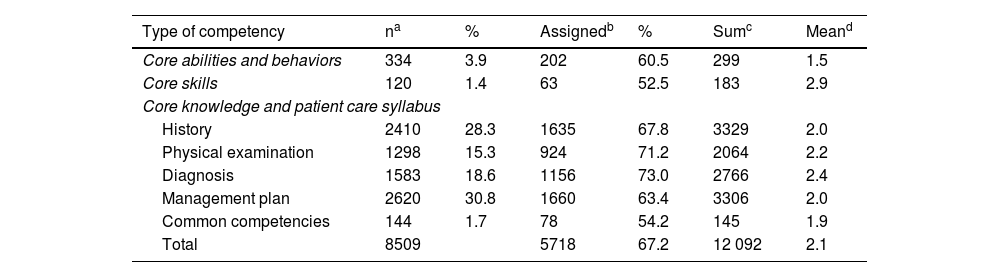

A total of 12 048 competency assignments were made, with an average of 10.8 competencies per activity. Table 1 presents the analysis of competencies per type of activity. Of the 8509 competencies included in the matrix (216 were newly defined), 5718 were addressed at least once in the Continuum activities. This amounts to 67.2% of the total (95% CI, 66.2%–68.2%). Each of these competencies was assigned a mean of 2.11 times (95% CI, 2.07–2.15; median, 2; range, 1–18; interquartile range, 2). Table 2 presents the distribution by type of competency.

Distribution of competencies by type of competency.

| Type of competency | na | % | Assignedb | % | Sumc | Meand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core abilities and behaviors | 334 | 3.9 | 202 | 60.5 | 299 | 1.5 |

| Core skills | 120 | 1.4 | 63 | 52.5 | 183 | 2.9 |

| Core knowledge and patient care syllabus | ||||||

| History | 2410 | 28.3 | 1635 | 67.8 | 3329 | 2.0 |

| Physical examination | 1298 | 15.3 | 924 | 71.2 | 2064 | 2.2 |

| Diagnosis | 1583 | 18.6 | 1156 | 73.0 | 2766 | 2.4 |

| Management plan | 2620 | 30.8 | 1660 | 63.4 | 3306 | 2.0 |

| Common competencies | 144 | 1.7 | 78 | 54.2 | 145 | 1.9 |

| Total | 8509 | 5718 | 67.2 | 12 092 | 2.1 | |

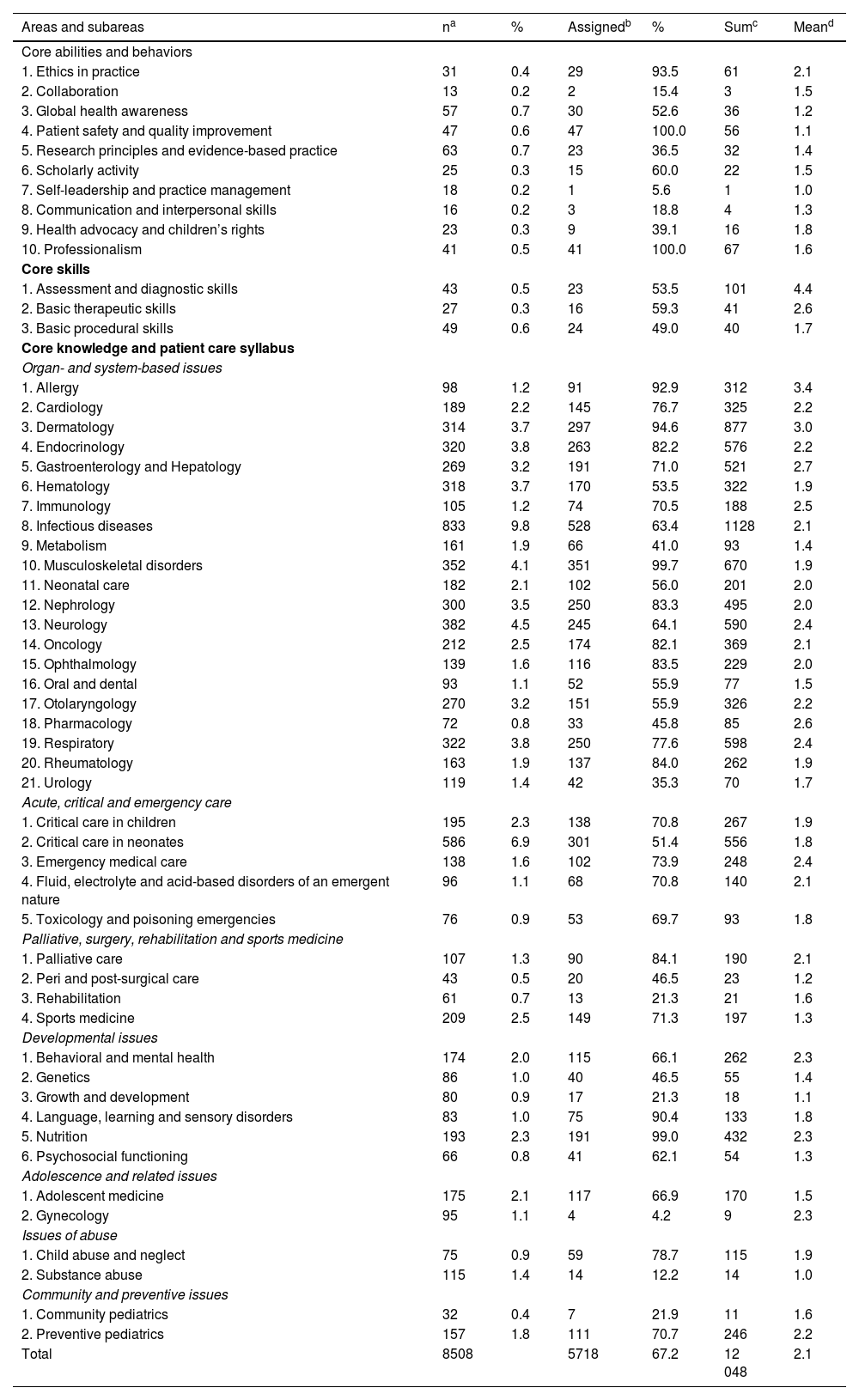

Table 3 shows the competencies covered by Continuum activities by content area. The mean competency coverage by content area was 60.9% (95% CI, 54%–67.8%; median, 64.1%; range, 4%–100%; interquartile range, 35.6%). Table 3 also reflects the total number of competency assignments, taking into account competencies that were assigned to more than one activity.

Assigned competencies by content area and subarea.

| Areas and subareas | na | % | Assignedb | % | Sumc | Meand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core abilities and behaviors | ||||||

| 1. Ethics in practice | 31 | 0.4 | 29 | 93.5 | 61 | 2.1 |

| 2. Collaboration | 13 | 0.2 | 2 | 15.4 | 3 | 1.5 |

| 3. Global health awareness | 57 | 0.7 | 30 | 52.6 | 36 | 1.2 |

| 4. Patient safety and quality improvement | 47 | 0.6 | 47 | 100.0 | 56 | 1.1 |

| 5. Research principles and evidence-based practice | 63 | 0.7 | 23 | 36.5 | 32 | 1.4 |

| 6. Scholarly activity | 25 | 0.3 | 15 | 60.0 | 22 | 1.5 |

| 7. Self-leadership and practice management | 18 | 0.2 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 1.0 |

| 8. Communication and interpersonal skills | 16 | 0.2 | 3 | 18.8 | 4 | 1.3 |

| 9. Health advocacy and children’s rights | 23 | 0.3 | 9 | 39.1 | 16 | 1.8 |

| 10. Professionalism | 41 | 0.5 | 41 | 100.0 | 67 | 1.6 |

| Core skills | ||||||

| 1. Assessment and diagnostic skills | 43 | 0.5 | 23 | 53.5 | 101 | 4.4 |

| 2. Basic therapeutic skills | 27 | 0.3 | 16 | 59.3 | 41 | 2.6 |

| 3. Basic procedural skills | 49 | 0.6 | 24 | 49.0 | 40 | 1.7 |

| Core knowledge and patient care syllabus | ||||||

| Organ- and system-based issues | ||||||

| 1. Allergy | 98 | 1.2 | 91 | 92.9 | 312 | 3.4 |

| 2. Cardiology | 189 | 2.2 | 145 | 76.7 | 325 | 2.2 |

| 3. Dermatology | 314 | 3.7 | 297 | 94.6 | 877 | 3.0 |

| 4. Endocrinology | 320 | 3.8 | 263 | 82.2 | 576 | 2.2 |

| 5. Gastroenterology and Hepatology | 269 | 3.2 | 191 | 71.0 | 521 | 2.7 |

| 6. Hematology | 318 | 3.7 | 170 | 53.5 | 322 | 1.9 |

| 7. Immunology | 105 | 1.2 | 74 | 70.5 | 188 | 2.5 |

| 8. Infectious diseases | 833 | 9.8 | 528 | 63.4 | 1128 | 2.1 |

| 9. Metabolism | 161 | 1.9 | 66 | 41.0 | 93 | 1.4 |

| 10. Musculoskeletal disorders | 352 | 4.1 | 351 | 99.7 | 670 | 1.9 |

| 11. Neonatal care | 182 | 2.1 | 102 | 56.0 | 201 | 2.0 |

| 12. Nephrology | 300 | 3.5 | 250 | 83.3 | 495 | 2.0 |

| 13. Neurology | 382 | 4.5 | 245 | 64.1 | 590 | 2.4 |

| 14. Oncology | 212 | 2.5 | 174 | 82.1 | 369 | 2.1 |

| 15. Ophthalmology | 139 | 1.6 | 116 | 83.5 | 229 | 2.0 |

| 16. Oral and dental | 93 | 1.1 | 52 | 55.9 | 77 | 1.5 |

| 17. Otolaryngology | 270 | 3.2 | 151 | 55.9 | 326 | 2.2 |

| 18. Pharmacology | 72 | 0.8 | 33 | 45.8 | 85 | 2.6 |

| 19. Respiratory | 322 | 3.8 | 250 | 77.6 | 598 | 2.4 |

| 20. Rheumatology | 163 | 1.9 | 137 | 84.0 | 262 | 1.9 |

| 21. Urology | 119 | 1.4 | 42 | 35.3 | 70 | 1.7 |

| Acute, critical and emergency care | ||||||

| 1. Critical care in children | 195 | 2.3 | 138 | 70.8 | 267 | 1.9 |

| 2. Critical care in neonates | 586 | 6.9 | 301 | 51.4 | 556 | 1.8 |

| 3. Emergency medical care | 138 | 1.6 | 102 | 73.9 | 248 | 2.4 |

| 4. Fluid, electrolyte and acid-based disorders of an emergent nature | 96 | 1.1 | 68 | 70.8 | 140 | 2.1 |

| 5. Toxicology and poisoning emergencies | 76 | 0.9 | 53 | 69.7 | 93 | 1.8 |

| Palliative, surgery, rehabilitation and sports medicine | ||||||

| 1. Palliative care | 107 | 1.3 | 90 | 84.1 | 190 | 2.1 |

| 2. Peri and post-surgical care | 43 | 0.5 | 20 | 46.5 | 23 | 1.2 |

| 3. Rehabilitation | 61 | 0.7 | 13 | 21.3 | 21 | 1.6 |

| 4. Sports medicine | 209 | 2.5 | 149 | 71.3 | 197 | 1.3 |

| Developmental issues | ||||||

| 1. Behavioral and mental health | 174 | 2.0 | 115 | 66.1 | 262 | 2.3 |

| 2. Genetics | 86 | 1.0 | 40 | 46.5 | 55 | 1.4 |

| 3. Growth and development | 80 | 0.9 | 17 | 21.3 | 18 | 1.1 |

| 4. Language, learning and sensory disorders | 83 | 1.0 | 75 | 90.4 | 133 | 1.8 |

| 5. Nutrition | 193 | 2.3 | 191 | 99.0 | 432 | 2.3 |

| 6. Psychosocial functioning | 66 | 0.8 | 41 | 62.1 | 54 | 1.3 |

| Adolescence and related issues | ||||||

| 1. Adolescent medicine | 175 | 2.1 | 117 | 66.9 | 170 | 1.5 |

| 2. Gynecology | 95 | 1.1 | 4 | 4.2 | 9 | 2.3 |

| Issues of abuse | ||||||

| 1. Child abuse and neglect | 75 | 0.9 | 59 | 78.7 | 115 | 1.9 |

| 2. Substance abuse | 115 | 1.4 | 14 | 12.2 | 14 | 1.0 |

| Community and preventive issues | ||||||

| 1. Community pediatrics | 32 | 0.4 | 7 | 21.9 | 11 | 1.6 |

| 2. Preventive pediatrics | 157 | 1.8 | 111 | 70.7 | 246 | 2.2 |

| Total | 8508 | 5718 | 67.2 | 12 048 | 2.1 | |

During the study period, Continuum, the online education platform of the AEP, offered 1118 activities to 22 342 users. A total of 5718 competencies were covered, enabling the development of more than two-thirds of the competencies proposed by the GPEC curriculum standards.4 To understand the magnitude of this figure, we must consider the large number of competencies proposed by the GPEC, many of which are repeated or diversified in different content areas (specialties) and types of competencies (history, physical examination, diagnosis, management plan). In comparison, other training curricula for general pediatrics, such as those developed by The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health or the American Board of Pediatrics, have far fewer elements.10–13

It is known that e-learning can complement formal in-person education during medical school,14 specialty training or clinical practice,15 especially in areas that tend to not be covered in depth16 or that are highly specialized.17,18 It is also useful for clinical scenarios that require standardized management, as it can improve the confidence of residents and adherence to clinical practice guidelines.19,20 In spite of this, there is still little objective evidence on the potential advantages of remote learning. Its effectiveness and impact on the performance of health care professionals and, to the extent possible, the impact on patient outcomes, all need to be evaluated.3

Based on our findings, it is reasonable to state that Continuum, built on the foundation of its matrix of competencies, enables and facilitates online learning of pediatrics competencies. More than two thirds of pediatrics competencies have been covered by the platform in its first decade in operation. At the same time, the platform hosts and organizes the training portfolios of the users, providing them with logging and tracking tools. Thus, the training portfolio becomes more than a mere collection of evaluations and attendance certificates. It turns into an actual résumé that defines the strengths and weaknesses of both the user’s training and the platform itself.

In addition, the aforementioned transition to competency-based education includes additional evidence through practical assessments within a progressive, inquiry-based and demonstrably competency-based learning plan.21 The Continuum competency matrix implements international standards for planning and implementing educational activities or courses. It promotes self-led learning, the development of clinical skills and critical thinking. There have been few previous similar experiences. Among them, we ought to highlight that of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, which has proven effective in the integration of standard curricula in e-portfolio training logs.10,21

The main challenge in covering the competencies of the GPEC syllabus lies in their uneven development across different areas of learning. This means that areas with more detailed competencies that break into a larger total number of competencies which, therefore, require a larger number of specific training activities to cover them. This makes it difficult for the platform to homogeneously cover all the skills and specialties within pediatrics; a lower percent coverage of an area’s competencies does not necessarily signal neglect of that particular area. To minimize this issue, Continuum structures and offers educational activities based on the different subspecialties of pediatrics.22–24

This probably gives rise to some of the heterogeneity in the coverage of competencies. The diverse profiles of the authors, combined with the variable contribution of the different committees and societies of the AEP, has influenced the achievements made in training. Thus, as would be expected, there is a correlation between the offered training courses and the degree of coverage of the competencies in their respective areas.

The content areas with the highest coverage (>90%) include “professionalism”, “patient safety and quality improvement”, “musculoskeletal disorders”, “allergy”, “dermatology” and “nutrition”. These cross-cutting general competencies apply to different areas of pediatrics knowledge, which is why their coverage predominates. Since the platform does not have a permanent team of instructors, at the outset, the development of educational activities was not planned to follow a uniform distribution by content area. However, after periodic reviews of the platform’s performance, it is possible to approach the development of new courses to cover underrepresented areas moving forward. The findings of our study can guide the optimization of the offered educational activities to learning areas that have not been covered yet.

We found differential behavior in activities such as “New in the literature” or “Highlighted articles”. These were influenced by the recent publications in the medical literature. On the other hand, the “Image of the week” and “Interactive clinical case” authors were sporadic collaborators not affiliated with Continuum. Both of these sections directly reflect clinical practice (“submitting what is managed in the real-world care setting”). Their contents, which align with the digital format with the use of cutaneous or radiological images, contribute to increasing the coverage of diagnostic competencies.

This study has some limitations. Although the results of the analysis show the competencies that can be acquired through the activities on our platform, it was not possible to estimate with certainty the actual learning of our students. Completing any activity requires an assessment test, but this does not guarantee an actual clinical impact on patient care. Assessing this impact is one of the challenges we should undertake in the future. On the other hand, given the observational nature of the study and the design of the matrix, we were unable to consider aspects such as whether the acceptance of training options is modified or influenced by the assigned competencies. We also could not infer whether students changed their training choices based on the absence or presence of specific competencies in their training portfolio.

In conclusion, the Continuum e-learning platform has made it possible to acquire more than two thirds of the competencies required for the practice of pediatrics based on the GPEC curriculum. Thus, the platform offers a broad range of educational activities that contributes to the development of an important part of the professional competencies in pediatric care and that support and facilitate continuing education. Still, we found imbalances in coverage between different content areas. These imbalances need to be considered to prioritize access to the underrepresented competencies in the future development of educational strategies.

FundingThis research project did not receive specific financial support from funding agencies in the public, private or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors contributed to the study concept and design. Materials were prepared and data collected and analyzed by all authors. Carlos Ochoa Sangrador and Carmen Villaizán Pérez wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors commented on this and subsequent versions of the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Directors: Javier González de Dios and Francisco Hijano Bandera. Coordinators: Alberto García-Salido, José María Garrido Pedraz, Rafael Martin Masot, Carlos Ochoa Sangrador, Esteban Peiró Molina, Manuel Praena Crespo, Carmen Villaizán Pérez and Pablo del Villar Guerra.