The protocol for the management of mild cranioencephalic trauma in the emergency department was changed in July 2013. The principal innovation was the replacement of systematic skull X-ray in infants with clinical observation. The aims of this study were to determine whether there was (1) a reduction in the ability to detect traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the initial visit to Emergency, and (2) a change in the number of requests for imaging tests and hospital admissions.

MethodologyThis was a retrospective, descriptive, observational study. Two periods were established for the study: Period 1 (1/11/2011–30/10/2012), prior to the implementing of the new protocol, and Period 2 (1/11/2013–30/10/2014), following its implementation. The study included visits to the emergency department by children ≤2 years old for mild cranioencephalic trauma (Glasgow Scale modified for infants ≥14) of ≤24h onset.

ResultsA total of 1,543 cases were included, of which 807 were from Period 1 and 736 from Period 2. No significant differences were observed as regards sex, age, mechanism, or risk of TBI. More cranial fractures were detected in Period 1 than in Period 2 (4.3% vs 0.5%; P<.001), without significant changes in the detection of TBI (0.4% vs 0.3%; P=1). However, there were more cranial X-rays (49.7% vs 2.7%; P<.001) and more ultrasounds (2.1% vs 0.4%; P<.001) carried out, and also fewer hospital admissions (8.3% vs 3.1%; P<.001). There were no significant differences in the number of computerised tomography scans carried out (2% vs 3%; P=.203).

ConclusionsThe use of clinical observation as an alternative to cranial radiography leads to a reduction in the number of imaging tests and hospital admissions of infants with mild cranioencephalic trauma, without any reduction in the reliability of detecting TBI. This option helps to lower the exposure to radiation by the patient, and is also a more rational use of hospital resources.

En julio 2013 se cambió el protocolo de manejo del traumatismo craneoencefálico leve en urgencias, siendo la principal novedad la sustitución sistemática de las radiografías craneales en lactantes por la observación clínica. Los objetivos son determinar si este cambio ha implicado: 1) una disminución en la capacidad de detección de lesiones intracraneales (LIC) en la visita inicial de urgencias y 2) cambios en la solicitud de pruebas de imagen e ingresos.

MetodologíaEstudio retrospectivo, descriptivo-observacional. Se establecen 2 periodos: periodo 1 (1/11/2011-30/10/2012), preimplantación nuevo protocolo, y periodo 2 (1/11/2013-30/10/2014), postimplantación. Se incluyen las consultas por traumatismo craneoencefálico leve a urgencias (escala Glasgow modificada para lactantes≥14) de≤24h de evolución de niños≤2años.

ResultadosSe incluyen 1.543 casos, 807 del periodo 1 y 736 del periodo 2, sin observarse diferencias significativas en sexo, edad, mecanismo y riesgo de LIC. En el periodo 1 se diagnostican más fracturas craneales que en el periodo 2 (4,3 vs. 0,5%; p<0,001) sin cambios significativos en la detección de LIC (0,4 vs. 0,3%; p=1). Asimismo, se realizan más radiografías de cráneo (49,7 vs. 2,7%; p<0,001), más ecografías (2,1 vs. 0,4%; p<0,001) e ingresan más casos (8,3% vs 3,1%; p<0,001). No se hallan diferencias significativas en las tomografías computarizadas realizadas (2 vs. 3%; p=0,203).

ConclusionesLa observación clínica como alternativa a la radiografía craneal permite reducir las pruebas de imagen y los ingresos en los lactantes con traumatismo craneoencefálico leve sin disminuir la fiabilidad diagnóstica de LIC. Esta opción permite la reducción de irradiación al paciente y un uso más racional de los recursos sanitarios.

Head trauma (HT) is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in children in developed countries.1–3 Approximately 3%–5% of paediatric visits to primary care centres and emergency departments (EDs) are due to HT, which are mild in 90% of cases.1,2 There are still several points of controversy in the management of HT,4 one of which is the role of skull radiography. Historically, the presence of a skull fracture has been considered a risk factor for traumatic brain injury (TBI),2,3,5 although the absence of the former does not rule out the latter. It is estimated that about 2% of children with HT may present with a skull fracture, a prevalence that increases in children aged less than 2 years,6–8 which is why skull radiography is still recommended in Spain for specific cases of young children with mild HT.9,10

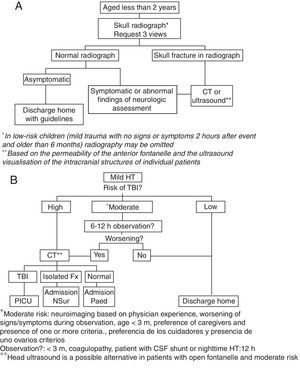

In 2013 we conducted a study in our ED11 that included 800 children aged 2 years or less with mild HT and found a low prevalence of TBI in this group of patients that was independent of the concomitant presence of skull fracture. With the aim of reducing exposure to radiation in these children, and in the awareness that skull radiography was no longer a recommended practice in the guidelines of countries with ample experience in the management of these patients,12–16 the protocol for the management of mild HT in our hospital was updated in July of the same year. The main change consisted in replacing skull radiography in children aged less than 2 years with mild HT and moderate risk of TBI by inpatient observation, with performance of head computed tomography (CT) in case of unfavourable progression. Fig. 1 shows the protocol in place until July 2013 (1A) and the protocol that has been applied since (1B).17,18

Algorithm for the management of mild head trauma in children aged less than 2 years in the hospital where the study was conducted (A: until July 2013; B: from July 2013).

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; Fx, fracture; HT, head trauma; NSur: neurosurgery; Paed, paediatrics ward; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

The primary objective of this study was to assess whether the implementation of the new protocol led to a reduction in the ability to detect TBI in the initial ED visit, and the secondary objective was to determine the changes in the requests for imaging tests and in hospital admissions that have occurred.

MethodsWe conducted a study in the ED of an urban tertiary care maternity and children's hospital with 264 paediatric beds that serves patients aged 0–18 years. The hospital serves a catchment area of 1800000 inhabitants and receives an average of 280 emergency visits a day.

The study had a retrospective, observational descriptive design. We established 2 study periods based on the introduction of the new HT protocol: period 1 (pre-implementation) from November 1, 2011 to October 30, 2012; and period 2 (post-implementation) from November 1, 2013 to October 30, 2014.

We searched electronic health records and selected ED discharge summaries for patients managed in the periods under study with a discharge diagnosis of HT (SEUP code 850.9).19 We included cases of mild HT (modified Glasgow Coma Scale for infants ≥14 points)20 in which the traumatic event had occurred within less than 24h. We excluded children with HT in the context of polytrauma, patients referred to the hospital that had already undergone imaging tests, and repeat visits considered part of the same episode.

We collected the following data for each visit: age; sex; mechanism of injury; score in the modified Glasgow Coma Scale for infants; risk of TBI (Table 1); diagnosis of skull fracture and/or TBI; performance of skull radiography, transfontanellar ultrasound and/or CT in the ED; patient destination after ED and outcome. We calculated the length of stay in the ED as the time elapsed between patient arrival and discharge, and length of hospital stay as the time elapsed between patient arrival to the ED and discharge from hospital.

Criteria to assess risk of traumatic brain injury in children aged less than 2 years with mild head trauma.

| Low risk | •Modified Glasgow coma scale for infants 15 points |

| •Normal neurologic assessment | |

| •Absence of sighs of skull fracture | |

| •Absence of associated symptoms | |

| •Mild traumatic mechanism | |

| •Absence of occipital, parietal or temporal cephalohaematoma | |

| Moderate risk | •Loss of consciousness lasting less than 5min |

| •History of vomiting | |

| •Moderate–severe headache or abnormal behaviour as reported by caregiver | |

| •Violent mechanism (motor vehicle accident with ejection of patient, death of another passenger, vehicle rollover, falls from heights >90cm, head struck by high-impact object) | |

| •Occipital, parietal or temporal cephalohaematoma | |

| •Convulsions immediately after trauma | |

| •Coagulopathy | |

| •Patient with cerebrospinal fluid shunt | |

| High risk | •Loss of consciousness longer than 5min |

| •Modified Glasgow coma scale for infants <15 points | |

| •Signs of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, Battle's sign, periorbital ecchymosis) | |

| •Palpable fracture | |

| •Penetrating trauma | |

| •Altered level of consciousness (agitation, somnolence, repetitive questions, amnesia, slowed speech) | |

| •Focal neurologic deficits | |

| •Seizures after symptom-free interval | |

| •Suspected child abuse |

Source: Trenchs and Muñoz-Santanach18.

We defined TBI as any finding secondary to HT in a neuroimaging test interpreted by a radiologist, with the exception of skull fracture. We defined clinically-important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI) as injury resulting in the death of the patient, indication of neurosurgery, mechanical ventilation lasting more than 24h, inotropic support or hospital admission lasting 2 or more nights due to HT.14

To determine the outcome of each patient, we reviewed the clinical notes entered during hospitalisation through discharge. For children that were discharged home from the ED, we reviewed the hospital's records as well as the linked Catalonia health system primary care records to identify potential complications of HT documented in subsequent visits.

We entered and processed the collected data in a Microsoft Access database. We tabulated data for quantitative and categorical variables. Data were subsequently analysed using SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). We have described quantitative variables as means or medians and categorical variables as percentages. We used statistical tests to analyse the distribution of data (Kolmogorov–Smirnov) and to compare quantitative data (Student's t, Mann–Whitney U) and qualitative data (chi square, contingency tables, Fisher's exact test). We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for proportions using the Wilson method. We considered P-values of less than .05 statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital.

ResultsWe included 1,543 visits; 807 (52.3%) in period 1 and 736 (47.7%) in period 2. We did not find significant differences between the two periods under study in patient age, sex, mechanism of injury, modified Glasgow Coma Scale for infants score during assessment at the ED, and risk of TBI (Table 2).

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of children aged less than 2 years with mild head trauma managed at the emergency department during the two periods.

| Characteristic | Period 1 (n=807) | Period 2 (n=736) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 11.0 (7.5–17.1) | 11.5 (7.1–17.3) | .752 |

| Male sex | 430 (53.3) | 386 (52.4%) | .742 |

| Documented HT mechanism | 782 | 672 | |

| Mechanism of fall | 703 (89.9%) | 587 (87.4%) | .126 |

| Glasgow 15 in ED | 807 (100%) | 734 (99.7%) | .227 |

| Risk of TBI | .133 | ||

| Low | 408 (50.6%) | 405 (55%) | |

| Moderate | 396 (49.1%) | 326 (44.3%) | |

| High | 3 (0.4%) | 5 (0.7%) | |

HT, head trauma; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range) and qualitative variables as absolute frequency (percentage).

During period 1, skull fracture was diagnosed in 35 infants (4.3%; 95% CI, 3.1%–6%), TBI in 3 (0.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%–1.0%) and ciTBI in 2 (0.3%; 95% CI, 0.07%–0.9%) compared to skull fracture in 4 infants (0.5%; 95% CI, 0.2%–1.4%; P<.001), TBI in 2 (0.3%; 95% CI, 0.07%–1.0%; P=1) and ciTBI in 1 (0.1%; 95% CI, 0.02%–0.8%; P=1) in period 2. Clinically important TBI was diagnosed based on hospitalisation lasting more than 48h in all cases, as no children required ventilatory or haemodynamic support or underwent neurosurgery.

Table 3 compares the management of these patients as regards imaging tests and hospital admission during the 2 periods. In patients admitted to hospital, the median length of stay was 36.4h in period 1 (interquartile range [IQR], 17.8–46.3) and 15.7h in period 2 (IQR, 12.9–19.6) (P<.001). In patients discharged home from the ED, the median length of stay in the ED was 1.8h in period 1 (IQR, 0.8–3.2) and 2h in period 2 (IQR, 1.2–3.7) (P<.001).

Imaging tests performed in the emergency department during both periods.

| Period 1 (n=807) | Period 2 (n=736) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging test | |||

| Skull radiograph | 401 (49.7) | 20 (2.7) | <.001 |

| Head CT scan | 16 (2.1) | 22 (3) | .203 |

| Head ultrasound | 17 (2.1) | 3 (0.4) | .003 |

| Hospital admission | 67 (8.3) | 23 (3.1) | <.001 |

CT, computed tomography.

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range) and qualitative variables as absolute frequency (percentage).

Thirteen patients (1.6%) made a repeat visit to the ED in period 1, compared to three (0.4%) in period 2, and complications from HT were diagnosed in none.

All patients with mild HT had good outcomes. No cases of TBI were detected in any of the children discharged home from the ED at a later time.

DiscussionThe results of our study show that the new protocol for the management of mild HT in children aged less than 2 years implemented in the ED is beneficial for both the patient and the health system. On the one hand, we found that the ability to detect TBI did not change significantly with the new protocol. On the other hand, there was a significant reduction in the number of radiographs and head ultrasound examinations and the percentage of patients admitted to hospital, as well as the associated lengths of stay. All of the above resulted in a decreased exposure to radiation for the patients and less inconvenience for their families, as well as lower costs for the health system. It is well known that ionising radiation is carcinogenic and that children are particularly sensitive to it, with a risk that is twice or three times that of the general population, so it is particularly important for the use of radiology techniques to be justified and optimised in paediatrics.21 Physicians generally have limited knowledge of the doses involved in the radiology tests that they request, and some surveys have found that physicians often underestimate the radiation dose and its associated risks.21–24 The new protocol introduced in our hospital helped eliminate nearly all exposure due to skull radiographs and limits the use of brain CT, which is the diagnostic test that is most concerning in terms of radioprotection.21,25,26

As we noted above, the reason skull radiography used in the management of children with HT in emergency settings is the increased risk of TBI in the event of a skull fracture; however, the limitations of radiography must be taken into account: it is difficult to interpret, has a low sensitivity for the diagnosis of TBI, and subjects children to a significant dose of ionising radiation.21 Due to these limitations, most current guidelines14–16 do not include radiography in the management of paediatric HT save for specific instances, such as the radiological assessment of young children when child abuse is suspected.27 Consistent with these international guidelines,14–16 the new protocol for HT uses clinical criteria to assess the risk of TBI and determine the approach to its management. Thus, patients with mild HT and moderate risk of TBI, who would have undergone skull radiography under the previous protocol, are now kept under observation in the ED until at least 6h have passed since the traumatic event. The study we present here demonstrates that observation is an adequate alternative to determine which patients are eligible for a brain CT scan, as the proportion of detected cases of TBI was similar in both periods, with no significant increase in the number of CT scans or evidence of delays in diagnosis. In this regard, it is also worth noting that the change in protocol did not result in a substantial increase in ED length of stay. This finding is probably due to the fact that while it may not have been explicitly included in the previous protocol, children with HT were also kept under observation. As for the length of stay in the ED of children not admitted to hospital, it is important to consider that they were kept under observation until at least 6h had elapsed from the traumatic event, so that length of stay was also influenced by the time elapsed between the event and the ED visit.

The reduction in the number of skull radiographs was associated to a decrease in the number of cases of skull fracture that were diagnosed. The latter was probably due to nondetection of fractures rather than their absence, as the samples in both periods were similar in terms of age and mechanisms of injury. The risk associated with failing to diagnose a skull fracture in this context is low, as fractures heal spontaneously in most cases.28,29 A small proportion of skull fractures can progress to a growing skull fracture, a rare complication that occurs in 1% of cases, mostly in patients with neurologic manifestations or a palpable fracture30,31 that would be identified by brain CT.

We found that the percentage of hospital admissions decreased by more than 60% and the length of hospitalisation by nearly 24h in period 2. This is probably due to a reduced detection of skull fractures, which were the reason for admitting most young children with mild HT to hospital. Current data show that when detected, most cases of linear nondisplaced skull fractures in children do not require hospital admission and that observation in the ED is sufficiently safe.29,32–34

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design, due to which we were unable to determine the mechanism of injury in all cases, and cannot rule out the possibility of inaccuracies in the clinical manifestations or physical examination findings recorded in the ED discharge summaries. Furthermore, we did not have data on the time elapsed between the traumatic event and the visit to the ED, so we could not determine the total number of hours of observation from the moment of HT. Another limitation is that we do not know the number of skull fractures that may have gone unnoticed in period 2 due to omitting skull radiography. However, we must take into account that we also cannot be certain that all skull fractures were diagnosed in period 1, as skull radiographs were not made in approximately 50% of patients. Another aspect to consider is that not all children underwent a CT scan, so it is possible, although very unlikely, that TBI or a growing skull fracture was subsequently diagnosed in some of the patients discharged home from the ED. We did not find any cases with complications in our review of additional visits by these patients to the hospital and of the Catalonia public health system records, so it would be reasonable to assume that they all had favourable outcomes.

To conclude, we would like to state that clinical observation as an alternative to skull radiography enables a decrease in the number of imaging tests and hospital admissions in young children with mild HT without diminishing reliability in diagnosing TBI. This option helps reduce radiation exposure in patients and make more rational use of health resources.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz-Santanach D, Trenchs Sainz de la Maza V, Maya Gallego S, Cuaresma González A, Luaces Cubells C. Observación clínica: una alternativa segura a la radiología en lactantes con traumatismo craneoencefálico leve. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:164–169.

Previous presentation: the results of this study were presented at the XX Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, receiving the award to the best oral communication in the meeting.