Vertigo is described as the illusion of intrinsic or extrinsic swaying or spinning motion of either the surroundings or the self. It is a relatively common condition in the paediatric population with an estimated prevalence of 5.20% and 6.00% and with a predominance of the female sex.1

These symptoms can result in delayed maturation of postural balance, coordination problems and the development of paroxysmal torticollis (head tilt) to compensate for the deficit.2 Challenges in the clinical evaluation, anxiety and the lack of communication ability can delay the ordering of vestibular function tests and therefore the definitive diagnosis.3

The aims of this study were basically twofold: first, to characterize the most frequent causes of vertigo in childhood from a comprehensive audiovestibular perspective and, second, to assess the potential association with anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with vestibular disorders.

We designed a cross-sectional retrospective observational study in a tertiary care centre. The sample included 46 patients who were followed for 4.32 years (range, 2–7), with a mean age of 10.19 years (SD, 6.10; range 6–14) and a predominance of female patients (71.73%; n=33). The statistical analysis was performed with the software R Studio, version 1.4.1106.

In the otoneurological examination using video nystagmography goggles (VideoFrenzel Interacoustics, Denmark), 28.26% of patients (n=13) tested positive for spontaneous nystagmus, with abnormal visual fixation indicative of a vestibular or central cause. The video head impulse test (vHIT, GN Otometrics, Denmark) yielded abnormal results in 15.21% (n=7), that is, detected impairment in the vestibulo-ocular reflex indicative of problems coordinating eye movements with head movements. Vestibular evoked myogenic potential testing (VEMPS, Eclipse, Interacoustics, Denmark) detected abnormalities in 45.65% (n=21), indicating impairment of the otholitic organs responsible for stabilising linear motion and maintaining balance and posture.

The mean pure tone average (PTA) (AC40, Interacoustics, Denmark) was 25.54dB (SD, 3.64), indicative of mild hearing impairment or loss. From an audiometric perspective, patients with a diagnosis of Ménière disease stood out on account of the aggressive progression typically observed in childhood-onset cases of this disease. However, the patients with the most severe hearing impairment were those with third window syndrome, such as perilymphatic fistula or enlarged vestibular aqueduct, 3 of whom required placement of cochlear implants.

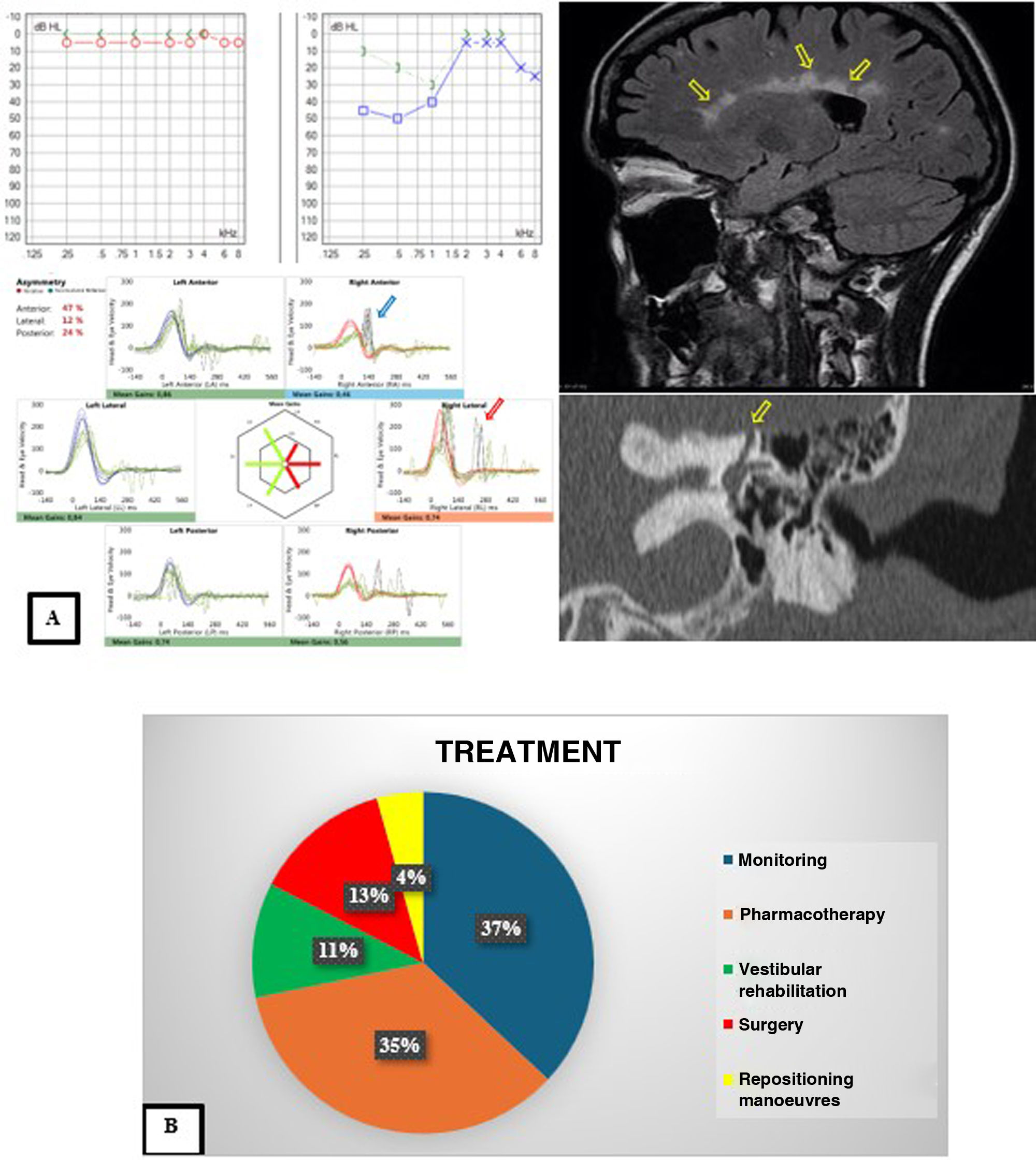

Some of the diagnoses made in the patients with the results of the audiovestibular tests can be found in Fig. 1A, Fig. 1B summarises the management, and Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of diagnosis and treatment.

(A) Images of different diagnostic tests performed to make the diagnosis. The top left image shows the audiogram of a patient with Ménière disease of the left ear, with the characteristic pattern of low frequency hearing loss. The bottom left image corresponds to the vHIT of a patient with vestibulopathy of the right ear, with impaired function on the right side and presence of both covert (blue arrow) and overt (red arrow) saccades. The top right image shows an MRI scan of a patient with vertigo and hearing loss due to multiple sclerosis, with the characteristic feature of Dawson fingers (yellow arrows). Lastly, the bottom right image corresponds to a patient with third window syndrome due to superior semicircular canal dehiscence (yellow arrow). (B) Summary of the treatments used to manage the diseases of the patients in the cohort.

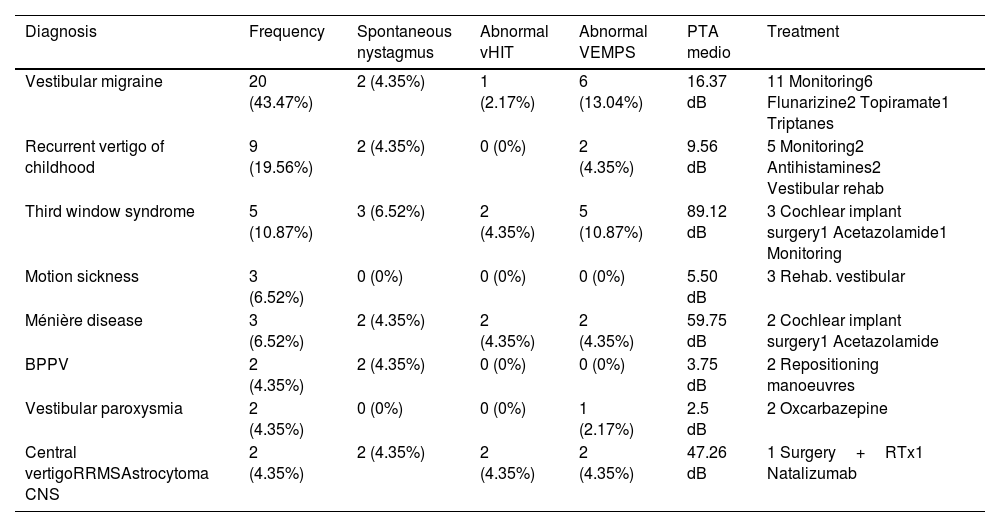

Summary of the diagnoses, testing results and treatments for the entire cohort of patients.

| Diagnosis | Frequency | Spontaneous nystagmus | Abnormal vHIT | Abnormal VEMPS | PTA medio | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vestibular migraine | 20 (43.47%) | 2 (4.35%) | 1 (2.17%) | 6 (13.04%) | 16.37 dB | 11 Monitoring6 Flunarizine2 Topiramate1 Triptanes |

| Recurrent vertigo of childhood | 9 (19.56%) | 2 (4.35%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.35%) | 9.56 dB | 5 Monitoring2 Antihistamines2 Vestibular rehab |

| Third window syndrome | 5 (10.87%) | 3 (6.52%) | 2 (4.35%) | 5 (10.87%) | 89.12 dB | 3 Cochlear implant surgery1 Acetazolamide1 Monitoring |

| Motion sickness | 3 (6.52%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5.50 dB | 3 Rehab. vestibular |

| Ménière disease | 3 (6.52%) | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (4.35%) | 59.75 dB | 2 Cochlear implant surgery1 Acetazolamide |

| BPPV | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (4.35%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3.75 dB | 2 Repositioning manoeuvres |

| Vestibular paroxysmia | 2 (4.35%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.17%) | 2.5 dB | 2 Oxcarbazepine |

| Central vertigoRRMSAstrocytoma CNS | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (4.35%) | 2 (4.35%) | 47.26 dB | 1 Surgery+RTx1 Natalizumab |

CNS, central nervous system; Rehab, rehabilitation; RRMS, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; RTx, radiation therapy.

It is worth noting that 16 of these patients (34.8%) had a previous diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorder. In fact, 10 of them (62.50%) were currently in treatment with antidepressant agents and/or psychotherapy at the time of the assessment of their vestibular manifestations. Thirty-five percent of patients with vestibular migraine (VM) (n=7) had psychosomatic symptoms, a proportion that increased to 44.44% (n=4) in patients with recurrent vertigo of childhood (RVC).

As we observed in our sample, VM or RVC are considered the main causes of episodic vertigo in the paediatric population with a corresponding reduction in the frequency of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), which may be due to anatomical differences that favour the trapping of otoconia in children,4 and ischaemic stroke, two of the most common causes in adult of both acute and chronic vertigo. What we propose is the investigation of whether childhood vertigo is frequently associated with an underlying anxious-depressive component. According to Erbek et al., there is a bidirectional relationship between neuro-otological and psychiatric disorders, since the symptoms of vestibular disorders tend to have an impact on the biopsychosocial domain. Symptoms may lead patients to withdraw with the aim of avoiding triggering stimuli, which in turn gives rise to anxiety, depression and/or behavioural disorders, causing emotional stress.5

In summary, the challenges met in the diagnosis of childhood vertigo often lead to the attribution of presenting symptoms to psychosomatic disorders rather than their more common causes, such as MV or RVC. The limitations to daily living that result from these symptoms cause an emotional stress that may mask an underlying vestibular disorder or a central nervous system disorder for which medical or surgical treatment is available, so audiovestibular testing should always be performed to avoid overlooking disorders that, with proper treatment, may have a minimal impact on the patient's quality of life.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

Informed consentWe obtained written informed consent for all the participants in the study.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved in April 2024 by the Ethics Committee of the Clínica Universidad de Navarra (file CEI 2024.168). In addition, the study was designed and conducted in adherence to the declarations of the Declaration of Helsinki de 1975.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.