Recent studies show an increase in the use of antidepressants in minors (younger than 18 years), although few antidepressants are indicated for this age group. The aim of our study was to calculate the annual prevalence of antidepressant use in children and adolescents and to review the adherence of prescription to current indications.

MethodsStudy of the prevalence of antidepressant use in minors based on the records of the Electronic Database for Pharmacoepidemiologic Studies in Primary Care (BIFAP) of Spain for the 2013–2018 period, considering at least one prescription per year for each patient.

ResultsThe prevalence of antidepressant prescription in patients from the BIFAP cohort increased between 2013 (7.97 prescriptions per 1000 patients) and 2018 (8.87 prescriptions per 1000 patients), in most groups and in both sexes. In this period, female patients received the most prescriptions, surpassing prescriptions in male patients by up to 2.5 points in the overall rates. In patients younger than 13 years, this trend was inverted and antidepressant use was higher in male patients. The prevalence of prescription rose with increasing patient age, as did the proportion of off-label prescriptions. The use of off-label medication decreased over time.

ConclusionsThere was a gradual increase in the prevalence of antidepressant prescription in minors younger than 18 years, with a predominance of the female sex. The high proportion of unapproved medication use in this age group calls for more thorough investigation of the risk-benefit balance of these treatments and of safer treatment alternatives.

Estudios recientes muestran un aumento del uso de antidepresivos en menores de 18 años aunque pocos de ellos cuentan con indicación en este grupo de edad. El objetivo de este estudio es calcular la prevalencia anual del uso de antidepresivos en niños y adolescentes y revisar la adecuación de la prescripción a las indicaciones actuales.

MétodosEstudio de prevalencia de la utilización de antidepresivos en menores de 18 años a partir de los registros de la Base de datos para la Investigación Farmacoepidemiológica en Atención Primaria (BIFAP) durante el periodo 2013–2018, considerando al menos una prescripción por año para un mismo paciente.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de prescripción de antidepresivos entre los pacientes de la cohorte BIFAP ha aumentado de 2013 (7,97 prescripciones/1000 pacientes) a 2018 (8,87 prescripciones/1000 pacientes) en la mayoría de los grupos y en ambos sexos. El sexo femenino suma la mayoría de las prescripciones, superando al masculino en hasta 2,5 puntos en las tasas generales. En menores de 13 años la tendencia se invierte y los antidepresivos predominan en los chicos. La prevalencia de las prescripciones aumenta con la edad de los pacientes, igual que la proporción de tratamientos fuera de ficha técnica. El empleo de fármacos sin indicación disminuye con el transcurso del tiempo.

ConclusionesObservamos un aumento gradual en la prevalencia de prescripción de antidepresivos en menores de 18 años, preponderante en el sexo femenino. La elevada proporción de uso de estos fármacos sin indicación autorizada, exige profundizar en el balance beneficio-riesgo y en alternativas de tratamiento más seguras.

Recent studies have evinced increases in the use of antidepressant drugs in children and adolescents in the past few years.1–4 These drugs were developed for use in adults, and few are indicated for treatment in these age groups.5

At present, only 7 antidepressants are indicated for use in individuals under 18 years in Spain. Each of them was authorised for use under very specific conditions and starting from a specific age.1,6 It is important to keep in mind that while the number of trials of antidepressant drugs in children and adolescents has been increasing, off-label prescriptions are still being made and are often associated with an increase in adverse events because safe dosage ranges and contraindications have yet to be established.7–9 While off-label use is frequent in the paediatric age group, the Committee on Medicines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Pediatrics) has underscored the need to improve the information available on medicines used in this population.10

In addition to the adverse reactions and side effects that antidepressants may trigger,11 it is important to consider the potential risk of suicidal behaviour associated with their use.11–15 The increasing reluctance worldwide to use antidepressants at these ages has motivated the performance of a review by the Committee on Medicines Used in Humans to assess the risk-benefit ratio of antidepressant use in the paediatric population.16 Its results showed that these drugs should not be used in children and adolescent outside the specific authorised indications, and in the sporadic cases in which physicians may choose to initiate treatment with one, the patient should be closely monitored.

Due to all of the above, it is important to know the current situation of antidepressant prescribing in children and adolescents. The aim of our study was to estimate the annual prevalence of antidepressant use in children and adolescents from 2013 to 2018 and to determine temporal trends during this period, in addition to assessing the appropriateness of prescribing based on current indications.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective observational study of antidepressant prescriptions made to individuals aged less than 18 years from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2018 through the electronic records held in the primary care pharmacological surveillance database of Spain (BIFAP: http://www.bifap.org),17 which has data on nearly 12 million patients in 10 autonomous communities in Spain updated since 2001. This study was conducted in the framework of the ANSIONIA project (pharmacological epidemiology of anti-anxiety and antidepressant treatment in children and adolescents), authorised by the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y productos Sanitarios (AEMPS, Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices) under file DPS-ANS-2019-01.

The data collected for the study included a numerical identification code for the patient, which allowed their anonymization, patient sex, date of inclusion and exit from the cohort, year of birth and information on the prescription based on Anatomical, Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) codes. Table 1 presents all the active substances included in this study for which indications for use in patients aged less than 18 years have been approved in Spain.

Classification and indications of antidepressants authorised in Spain for use in individuals aged less than 18 years.

| ATC code | Active ingredient | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Tricyclic antidepressants (TAD) | ||

| N06AA02 | Imipramine | Nocturnal enuresis from age 5 years |

| N06AA04 | Clomipramine | OCD and nocturnal enuresis from age 5 years. |

| N06AA06 | Trimipramine | Depressive mood and anxiety and sleep disturbances from age 12 years. |

| N06AA09 | Amitriptyline | Persistent nocturnal enuresis from age 6 years after failure of other approaches |

| N06AA10 | Nortriptyline | Treatment de la depression, bipolar disorder and atypical depression from age 6 years. |

| N06AA12 | Doxepin | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | ||

| N06AB03 | Fluoxetine | Moderate to severe depression episodes in individuals aged more than 8 years who do not respond to psychotherapy. |

| N06AB04 | Citalopram | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| N06AB05 | Paroxetine | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| N06AB06 | Sertraline | OCD from age 6 years. |

| N06AB08 | Fluvoxamine | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| N06AB10 | Escitalopram | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| Monoaminoxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | ||

| N06AF04 | Tranylcypromine | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| N06AG02 | Moclobemide | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| Dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (DSNRIs) | ||

| N06AX16 | Venlafaxine | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| N06AX21 | Duloxetine | Safety and efficacy not evaluated in paediatric age group |

| N06AX23 | Desvenlafaxine | Safety and efficacy not evaluated in paediatric age group |

| Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) | ||

| N06AX12 | Bupropion | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) | ||

| N06AX18 | Reboxetine | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| Atypical antidepressants | ||

| N06AA21 | Maprotiline | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| N06AX03 | Mianserin | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| N06AX05 | Trazodone | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| Other antidepressants | ||

| N06AX01 | Oxitriptan | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| N06AX11 | Mirtazapine | Should not be used before age 18 years. |

| N06AX14 | Tianeptine | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| N06AX22 | Agomelatine | Safety and efficacy not evaluated in paediatric age group |

| N06AX26 | Vortioxetine | Not recommended before age 18 years. |

| Compounding | ||

To calculate the prevalence of antidepressant use in each year under study and its temporal trends, we counted the total number of prescriptions (were there more than 1) for different antidepressants given to each patient. The population on which we made these calculations comprised all individuals included in the BIFAP cohort in each year under study. Also, to analyse differences in prescribing based on patient sex, we analysed the total number of prescriptions made to male and female patients for each subgroup of antidepressants. Similarly, we analysed differences in prescribing based on patient age, excluding records for children under 6 years, as none of the active substances under study was indicated for use in this age group. We calculated the total number of prescriptions per subgroup of antidepressants by adding the prescriptions for all the active substances included in each of the subgroups.

Lastly, to assess whether antidepressant prescribing adhered to current recommendations, we divided records in 2 categories: prescription for indication of the active substance under conditions authorised by the AEMPS, and lack thereof.

ResultsThe number of prescriptions for antidepressants has been increasing, from 7.97 prescriptions per 1000 patients in 2013 to 8.87 prescriptions per 1000 patients in 2018, except in years 2014 and 2015 and between 2017 and 2018. The year with the greatest number of prescriptions in the period under study was 2016, and 2013 was the year with the fewest prescriptions. Table 2 shows the annual prevalence of antidepressant prescribing throughout the study period (2013–2018).

Annual prevalence of antidepressant prescription per 1000 patients in the BIFAP cohort by patient sex and therapeutic subgroup.

| Subgroup | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female patients (n) | Male patients (n) | Female patients (n) | Male patients (n) | Female patients (n) | Male patients (n) | |||||||

| 435 805 | 458 324 | 445 562 | 469 847 | 445 190 | 469 676 | |||||||

| n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | |

| TADs | 411 | 0.943 | 186 | 0.406 | 424 | 0.952 | 188 | 0.400 | 438 | 0.984 | 192 | 0.409 |

| SSRIs | 1483 | 3.403 | 1080 | 2356 | 1781 | 3997 | 1127 | 2399 | 1745 | 3920 | 1129 | 2404 |

| Other | 119 | 0.273 | 57 | 0.124 | 128 | 0.287 | 55 | 0.117 | 90 | 0.202 | 46 | 0.098 |

| Atypical | 30 | 0.069 | 16 | 0.035 | 43 | 0.097 | 23 | 0.049 | 44 | 0.099 | 27 | 0.057 |

| DSNRIs | 75 | 0.172 | 49 | 0.107 | 128 | 0.287 | 55 | 0.117 | 103 | 0.231 | 50 | 0.106 |

| NRIs | 8 | 0.018 | 17 | 0.037 | 8 | 0.018 | 15 | 0.032 | 6 | 0.013 | 14 | 0.030 |

| NDRIs | 5 | 0.011 | 6 | 0.013 | 8 | 0.018 | 15 | 0.032 | 11 | 0.025 | 6 | 0.013 |

| MAOI | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 |

| Total | 2131 | 4.890 | 1411 | 3079 | 2520 | 5656 | 1478 | 3146 | 2437 | 5474 | 1464 | 3117 |

| Annual rate | 7968 | 8801 | 8591 | |||||||||

| Subgroup | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female patients (n) | Male patients (n) | Female patients (n) | Male patients (n) | Female patients (n) | Male patients (n) | |||||||

| 436 326 | 460 773 | 427 566 | 451 185 | 433 312 | 457 013 | |||||||

| n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | |

| TADs | 424 | 0.972 | 179 | 0.388 | 421 | 0.985 | 194 | 0.430 | 435 | 1004 | 191 | 0.418 |

| SSRIs | 1800 | 4125 | 1185 | 2572 | 1765 | 4128 | 1123 | 2489 | 1720 | 3969 | 1124 | 2459 |

| Other | 117 | 0.268 | 48 | 0.104 | 116 | 0.271 | 58 | 0.129 | 137 | 0.316 | 71 | 0.155 |

| Atypical | 45 | 0.103 | 35 | 0.076 | 52 | 0.122 | 34 | 0.075 | 49 | 0.113 | 35 | 0.077 |

| DSNRIs | 93 | 0.213 | 43 | 0.093 | 88 | 0.206 | 38 | 0.084 | 97 | 0.224 | 42 | 0.092 |

| NRIs | 2 | 0.005 | 10 | 0.022 | 3 | 0.007 | 4 | 0.009 | 3 | 0.007 | 1 | 0.002 |

| NDRIs | 11 | 0.025 | 9 | 0.020 | 5 | 0.012 | 6 | 0.013 | 7 | 0.016 | 6 | 0.013 |

| MAOIs | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 |

| Total | 2492 | 5711 | 1509 | 3275 | 2450 | 5730 | 1457 | 3229 | 2448 | 5650 | 1470 | 3217 |

| Annual rate | 8986 | 8959 | 8866 | |||||||||

DSNRIs, dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; MAOIs, monoaminoxidase inhibitors; NDRIs, norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors; NRIs, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TADs, tricyclic antidepressants.

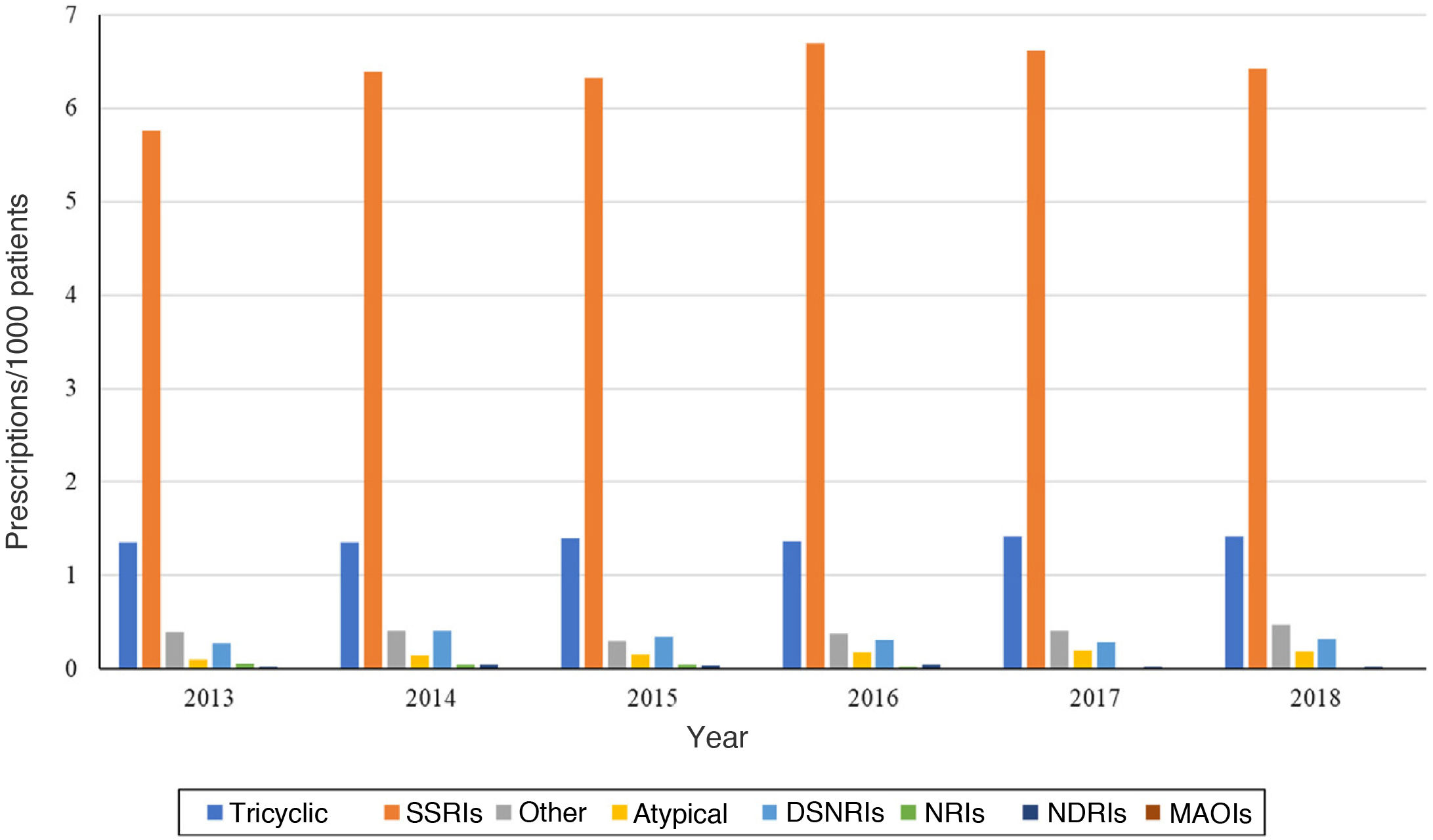

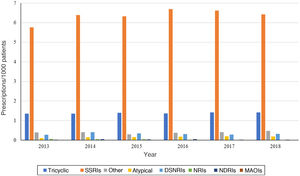

Analysing the trends in prescribing during the study period, we found an increase in the number of prescriptions per 1000 patients in the BIFAP in nearly all antidepressant subgroups. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) remained the most frequently prescribed subgroup throughout the 6-year period, with a prescribing prevalence up to 5 points greater compared to the second leading subgroup, tricyclic antidepressants (TADs), peaking in 2016 (Fig. 1). The only exception involved norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), the least used subgroup, for which prescribing declined between 2013 and 2018. We observed a similar trend in norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), with prescriptions declining between 2013 and 2016, increasing to the initial frequency in 2017 and exceeding it in 2018.

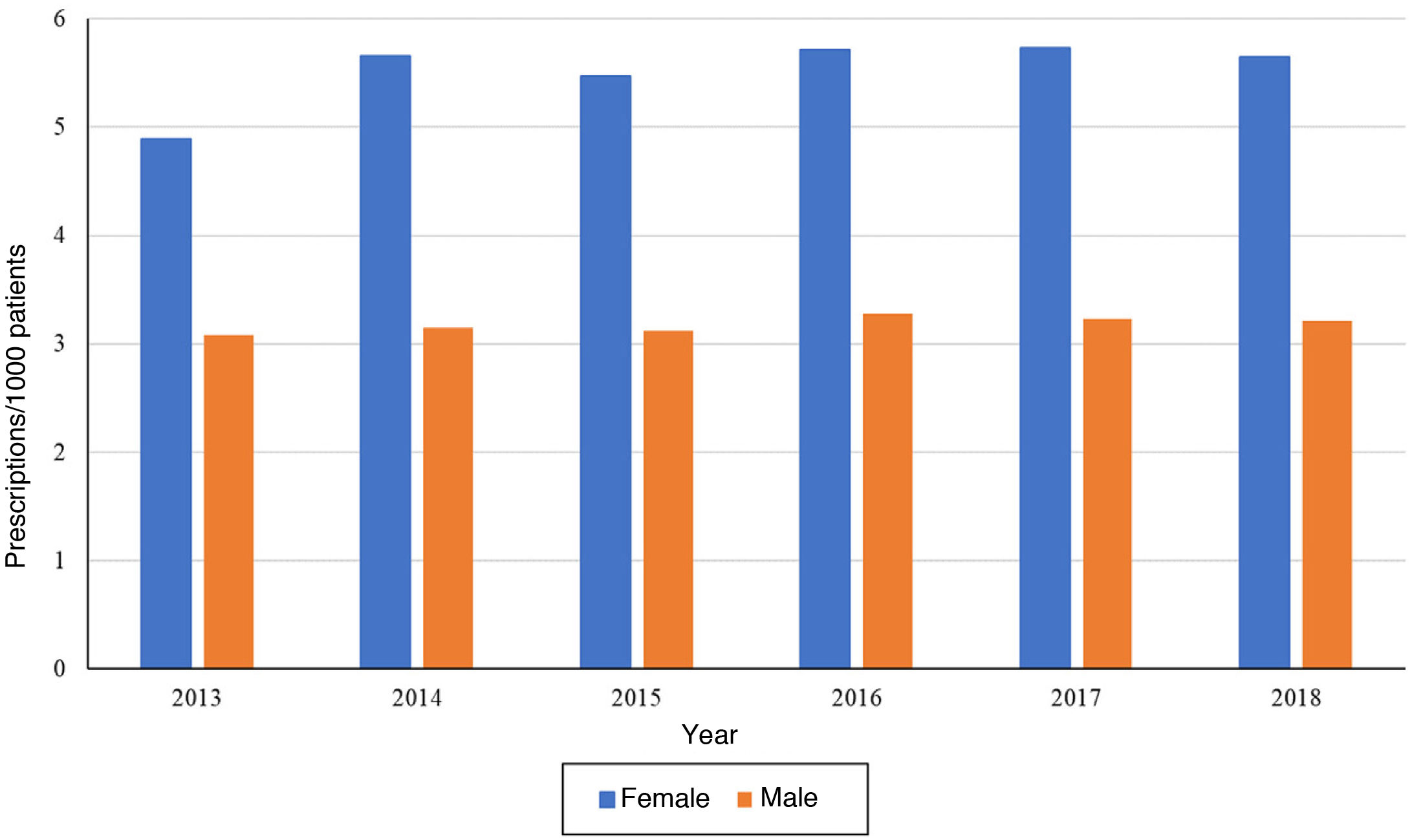

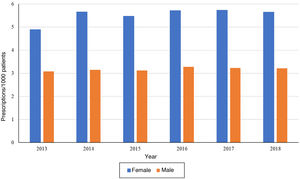

On one hand, when it came to patient sex, we found that the temporal trends in the frequency of prescription were the same. We ought to highlight that the number of prescriptions per 1000 patients was greater in female patients compared to male patients in each of the years under study (Fig. 2). The temporal trends by antidepressant subgroup were the same in patients of either sex and were consistent with the overall trends.

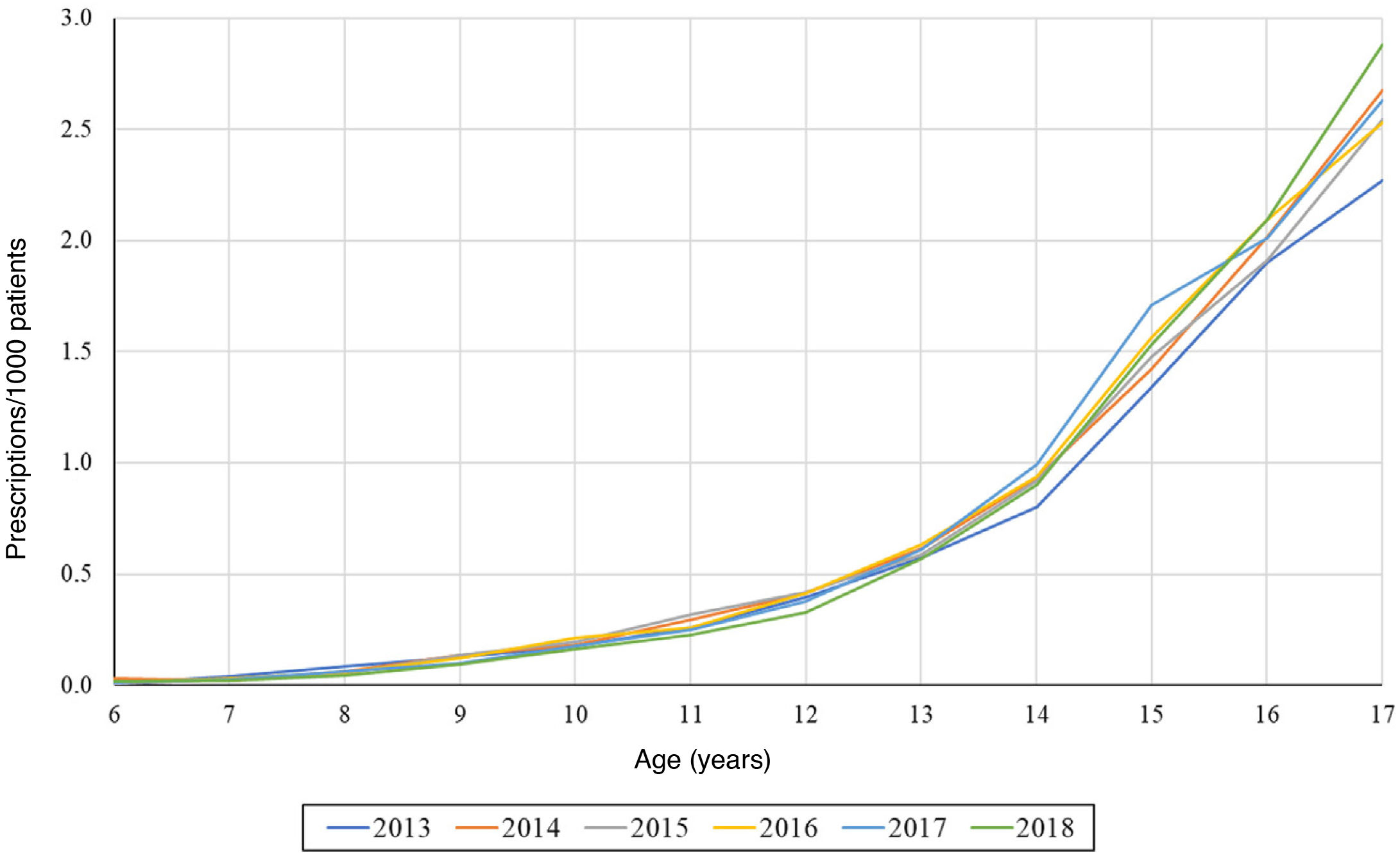

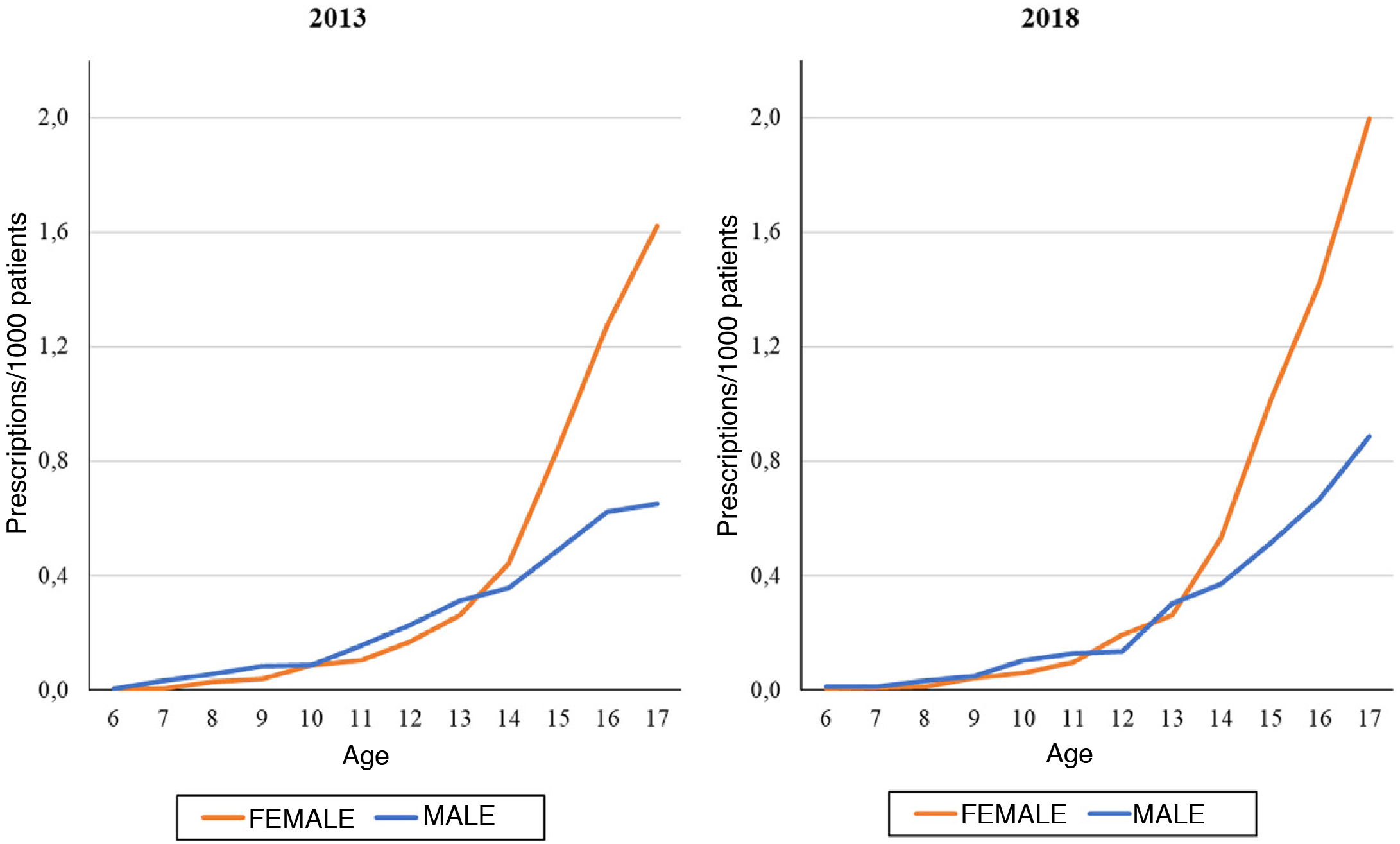

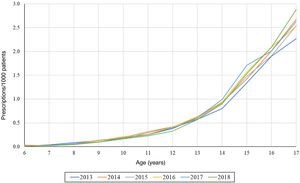

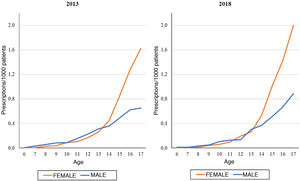

On the other hand, we found that the number of prescriptions per 1000 patients in the BIFAP cohort increased progressively with age, and that this increase was more marked in adolescence (Fig. 3). This means that while in patients aged less than 13 years there were no differences based on sex (Fig. 4), the overall frequency of prescription (not taking age into account) was greater in female patients. We also found a decreasing trend in the frequency of prescription in patients aged 6–13 years throughout the study period.

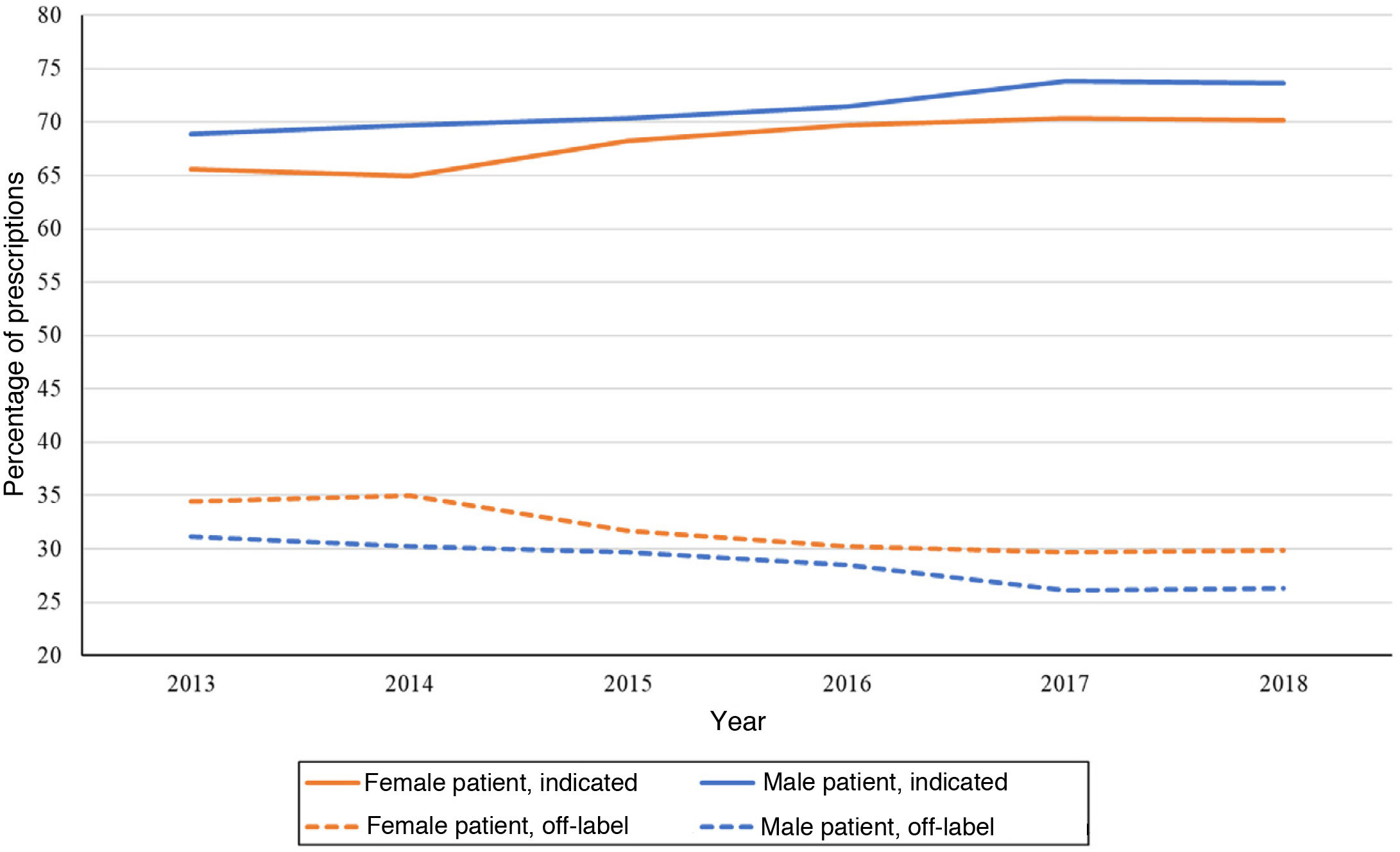

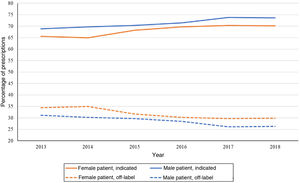

Fig. 5 shows the variation in antidepressant prescribing in male and female patients based on whether the use of given active substances was indicated in the patient. Another difference between the sexes emerged, for while more prescriptions were made to female patients, the percentage of prescriptions that adhered to established indications was between 2% and 4% lower in female versus male patients throughout the study period.

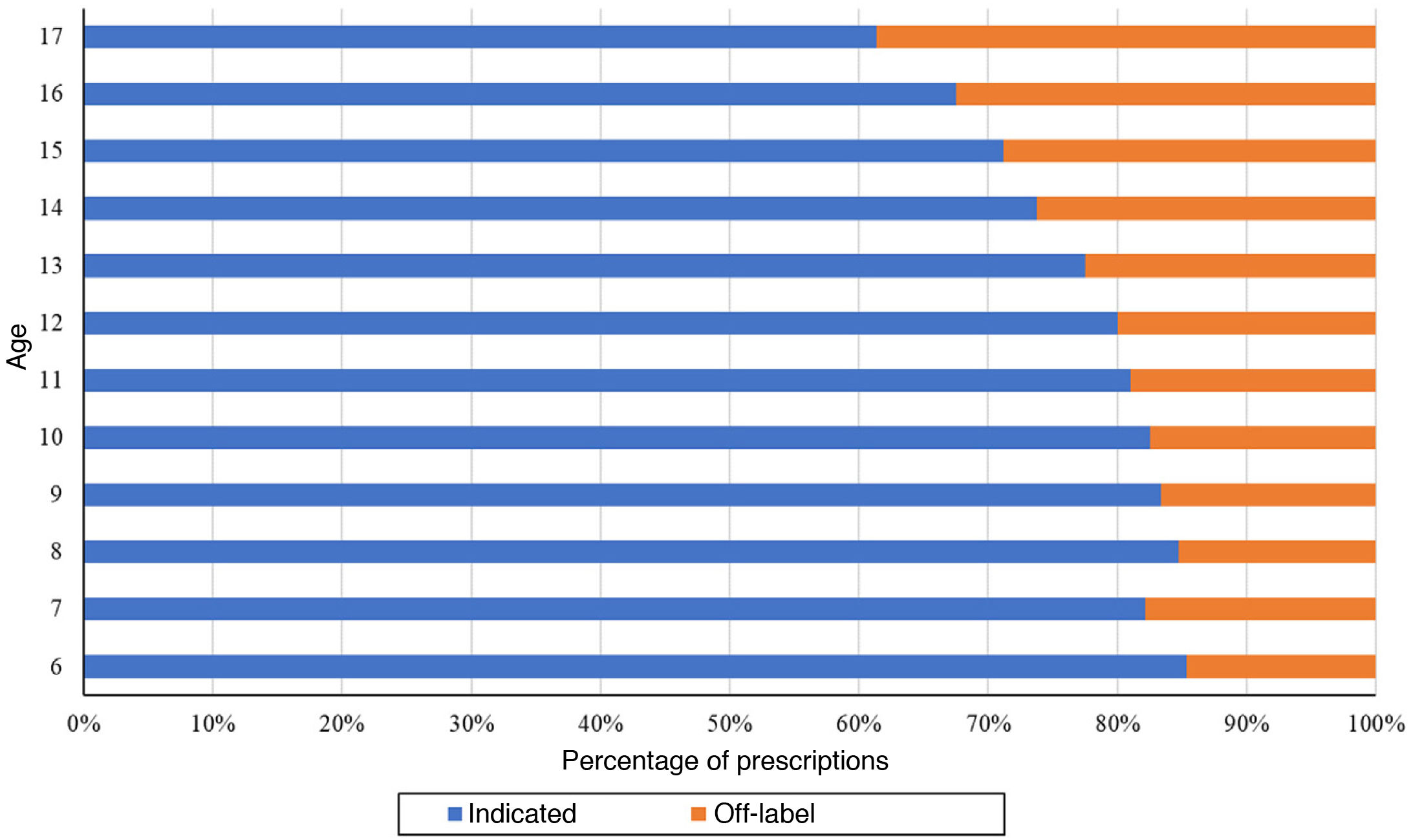

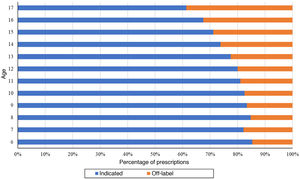

The proportion of off-label antidepressant prescriptions increased with age, and therefore the proportion of indicated antidepressants decreased with age, with a predominance of off-label prescription in individuals aged 14 years or older (Fig. 6).

DiscussionOur findings evince a gradual increase in the frequency of prescription of antidepressants to children and adolescents in the period under study. This increase was consistent with what has been previously described by other authors in relation to the use of antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs. In recent decades, there has been a sustained increase in antidepressant prescribing in many countries, including countries in Western Europe and the United States. The prescribing prevalence rates found in the analysis of the BIFAP database were greater compared to the frequencies reported in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and France, but lower compared to the frequencies reported in the United States, Norway and the United Kingdom.1,3,7,8,19–22 Revet et al.7 found an increase of 3.9% in antidepressant prescribing between 2009 and 2016 in France, with the prevalence increasing from 0.51% to 0.53%. These values were very low compared to the results published by Hoffmann et al.,8 who, analysing antidepressant prescription trends in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States between 2005 and 2012 found increases ranging from 17.6% in the Netherlands to 60.5% in Denmark, where the prevalence increased from 0.61% to 0.98%. Of these 5 countries, Germany was the one with the lowest prevalence (0.48% in 2012). Hoffmann et al.8 also observed an increase in Germany, where the prevalence rose from 0.32% in 2005 to 0.48% in 2012. Sarginson et al.1 found similar results in the United Kingdom, where the prevalence of antidepressant prescription was 0.47% in 2002 and 0.49% in 2015. On the other hand, John et al.21 explored this phenomenon by analysing the incidence and not the prevalence, and found the same trend in the data, with an increase from 5.26 to 7.69 new prescriptions per 1000 individuals aged 6–18 years by year 2013.

Prescribing of the different antidepressant subgroups increased over the 6 years under study with the exception of NRIs and NDRIs. The decrease in reboxetine prescriptions could be due to the controversy surrounding its effectiveness compared to placebo, a lower response rate compared to SSRIs and higher rates of attrition compared to more recently developed drugs.23,24 This was not the case in France, Germany or the United Kingdom, where prescription of TADs and other non-SSRI antidepressants has been steadily declining. When making this comparison, it is important to take into account that in Spain, 5 of the 7 antidepressants authorised for use in the paediatric population belong to the TAD subgroup. The predominance of SSRIs over all other types of antidepressants was a pattern consistent with the trends observed in other European countries and the United States. The most frequently prescribed active substance in patients in the BIFAP cohort was sertraline, followed by fluoxetine, in every year under study. This was consistent with the data published for countries like Sweden2 or France,7 while in Germany and the United Kingdom fluoxetine and citalopram were the most frequently prescribed antidepressants.1,3,8,21

The differences in prescribing observed between the sexes are not unique to this cohort, but have been described before repeatedly. We found a predominance of antidepressant prescribing in female minors, compared to the findings of Steinhausen et al.,18 Hartz et al.19 and Steffenak et al.24 regarding treatment with other psychotropic drugs, such as stimulants. When considering the use of antidepressants in isolation, those authors also found the trend observed in our study.

Patient age is an important factor in this study, as most antidepressants should not be used in individuals aged less than 18 years (only 7 of the drugs in the analysis have indications for use in specific paediatric age groups specified in the summary of product characteristics). While the frequency of prescription increased with age, this was not a linear trend. The most significant increase took place in early adolescence, when trends change and prescribing becomes more frequent in female versus male individuals, which is consistent with the hypothesis that most mood and anxiety disorders have onset in this stage of development.5,25 Between 2013 and 2018, the prevalence kept increasing overall, while decreasing in children aged 6–13 years, consistent with the findings of Revet et al.7 in France, where there was a slight increase in the general population and in adolescents aged 12–17 years, but a decrease in children aged 6–11 years group. Similar results have been reported by Sarginson et al.1 in the United Kingdom and Hoffmann et al.8 in Germany. Other studies in several different countries have evinced increases in every age group.2,19,26

Despite the drawbacks of treatment with antidepressants in children and adolescents, both in regard to the authorization for their use by health care authorities and the risk-benefit ratio, especially considering aggressive behaviours and the risk of suicide,27,28 our analysis evinced a large proportion of patients given prescriptions for active substances whose summaries of product characteristics do not include indications for these age groups. In 2013, such off-label prescriptions amounted to 33.12% of prescribed treatments, which stood in contrast to the data published by Lagerberg et al.2: in the same year, only 10% of antidepressant prescriptions in Sweden were for active substances not authorised for use in paediatric age ranges, once again with a higher proportion in adolescents. Although in the period under study off-label prescription gradually declined, 28.50% of the sample had off-label prescriptions in 2018. Revet et al.7 also found a decline in the proportion of off-label prescriptions in the general population (6−17 years). Once again, there were differences based on sex, as the proportion of off-label prescription in male patients was 2%–4% lower compared to female patients in the overall sample, although these disparities between the sexes were nearly negligible at certain ages. We found a directly proportional association between age and off-label prescribing.

This study of the BIFAP cohort, as is the case of other studies conducted using databases, has a series of limitations. First of all, it is important to consider that most records correspond to prescriptions of an antidepressant, and data on their dispensation was rarely available. Thus, it is possible that the collected data do not reflect the actual use of these drugs, as we do not know whether they were eventually consumed. Secondly, we ought to highlight that an increase in the frequency of prescription is not necessarily due to an increase in the prevalence of one or more specific disorders, as the indications or diagnoses that motivated the prescription of the antidepressants were not documented. In addition, it is possible that the prevalence rates found in our study underestimate the actual prevalence in the total population, as the data only refer to prescriptions made by primary care physicians registered in the databases of 10 of the 17 autonomous communities in Spain. Therefore, it may not be possible to extrapolate the results to the entire population aged less than 18 years of Spain.

In conclusion, we can highlight that in the 6 years under study, we found evidence of an increased prevalence of prescribing to children and adolescents in the BIFAP cohort for most antidepressant subgroups. This increase was more marked in female individuals, in whom the prevalence of antidepressant prescription was greater compared to male individuals at all times. In younger children, the prevalence of prescription has been declining over time. In addition, it is much lower compared to the prevalence found in adolescents, and with a lower proportion of active substances used off-label. This does not justify the high percentage of treatments with drugs whose use is not authorised or is recommended against in the paediatric population. Given the adverse effects associated with antidepressant use and the results of our study, we believe it would be advisable to carry out more studies regarding the risk-benefit ratio of these drugs in the paediatric age group and to seek safer treatment alternatives.

Conflict of interestNone.