In 2012, the Adolescents with Cancer Working Group published the results of a survey on care delivery for the adolescent population in Spain as a starting point for future intervention. The aim of this nationwide survey was to outline the current situation and assess whether the implemented strategies have resulted in changes in care delivery.

Material and methodsSurvey consisting of the same items analysed and published in 2012. The questionnaire was structured into sections devoted to epidemiology, psychosocial care, infrastructure, treatment and follow-up of adolescents with cancer. It was submitted to all hospitals in Spain with a paediatric haematology and oncology unit. We conducted a descriptive analysis of the results.

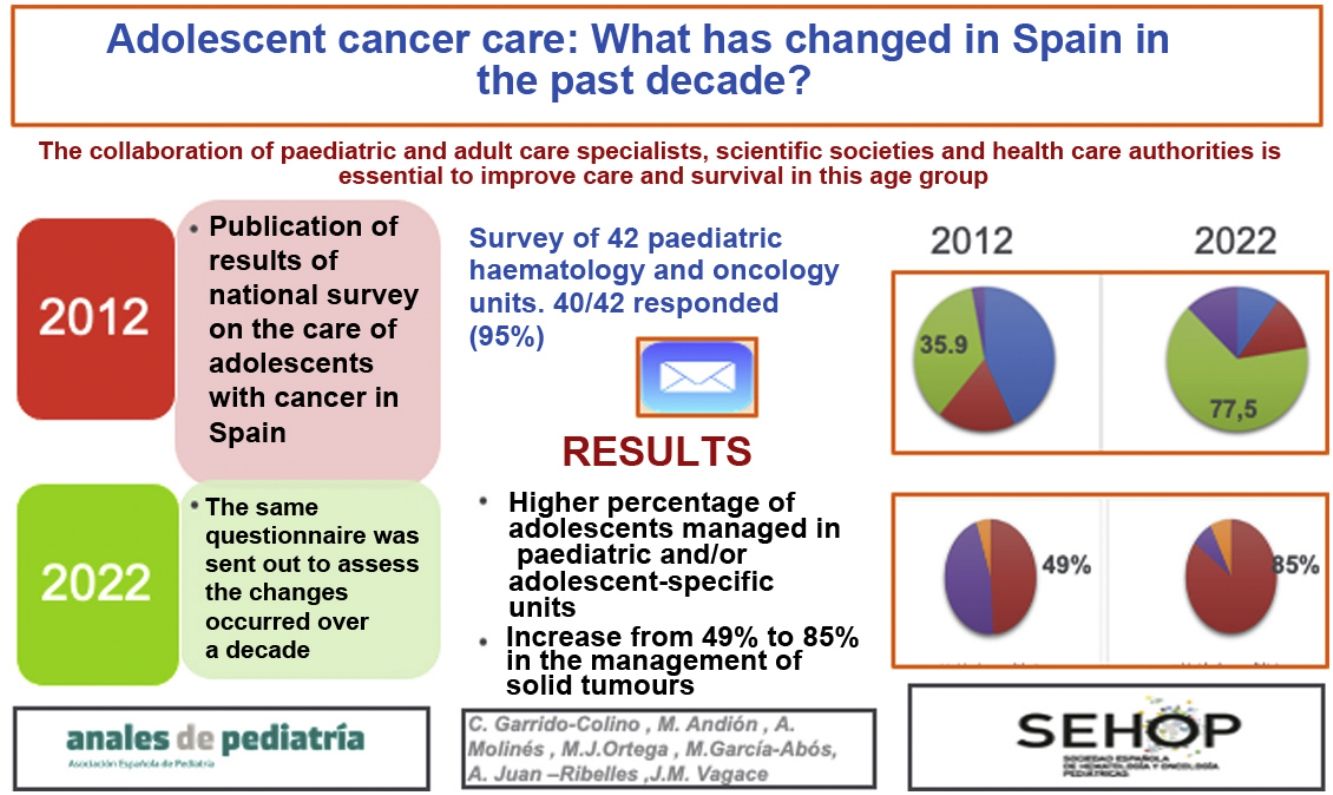

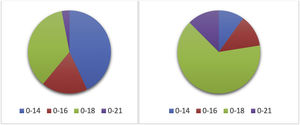

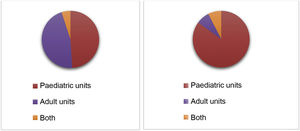

ResultsThe percentage of patients aged up to 18 years managed in paediatric units has increased from 35.9% to 77.5% in the past decade. The proportion of malignant blood tumours treated in paediatric units increased from 31% to 52%, and the proportion of solid tumours from 49% to 85%. In 2012, 30 units (out of 39) reported that new cases in adolescents amounted to up to 10% of the total. At present, only 14 (out of 40) continue to report this percentage. A decade ago, there were no specific adolescent cancer units in Spain. Now, 7 centres (out of 40) have specific multidisciplinary units. There has been little change in psychological support services for adolescents. The follow-up of survivors is carried out by paediatric specialists in 82.5% of the hospitals.

ConclusionsThe efforts made to centralise the care of adolescents with cancer in specific multidisciplinary adolescent units or, failing that, paediatric units, is reflected in the changes in care delivery in Spain in the past decade. Much remains to be done in key components of the management of adolescents with cancer.

En el año 2012, el grupo de trabajo de adolescentes con cáncer publicó los resultados de una encuesta sobre la asistencia a adolescentes en España, como punto de partida para futuras actuaciones. Evaluar si las líneas de trabajo han supuesto cambios asistenciales en la última década.

Material y métodosEncuesta, que consta de las mismas preguntas analizadas y publicadas en el año 2012. La encuesta se divide en: epidemiología, atención psicosocial, infraestructuras, tratamiento y seguimiento de los adolescentes con cáncer.

Se envío a todos los hospitales con Unidades de hematología y Oncología Pediátrica.

Análisis estadístico descriptivo de los resultados.

ResultadosEl porcentaje de pacientes hasta 18 años tratados en unidades pediátricas ha aumentado del 35.9% al 77.5%. Las hemopatías malignas tratadas en unidades pediátricas se incrementan del 31% al 52%. Los tumores sólidos del 49% al 85%. En 2012, 30 (39) unidades, referían que los casos nuevos de adolescentes representaban un 10%. Actualmente 14 (40), mantienen este porcentaje. Hace una década no existían unidades específicas para adolescentes con cáncer en España. Actualmente, 7 (40) centros disponen de unidades. La atención psicológica para adolescentes apenas ha variado. El seguimiento de supervivientes se realiza por especialistas pediátricos en el 82.5% de los centros.

ConclusionesEl trabajo para centralizar los cuidados de adolescentes con cáncer en unidades específicas multidisciplinarias o en su defecto pediátricas, se ve reflejado en los cambios en la atención sanitaria en nuestro país en la última década. Aún queda un largo recorrido en pilares fundamentales en el abordaje de esta población.

In the past 20 years, the importance of having specialised units to address the specific needs of adolescents with cancer has become evident, and this has turned into a clinical and research field that is prioritised to improve the care and survival of this group of patients1–6.

In the last 50 years, survival has improved significantly in both childhood cancers (age <14 years) and adult cancers7. In Europe, survival studies in adolescents and young adults evince advances in survival worldwide1,8,9. The EUROCARE-5 study, which compares the 5-year overall survival in adults, children and adolescents, has found lower survival in adolescents in different types of tumours10. This difference has multifactorial roots, and some of the described causes include tumour biology, delays in diagnosis, poor adherence to treatment in adolescents and a paucity of professionals specifically trained to manage this age group11–13. This difference is also associated to the lack of specific treatment protocols and infrequent inclusion in clinical trials. If we focus exclusively on adolescents aged 14–19 years, only 10% of these patients were included in clinical trials in the United States between 1975 and 199714,15.

In the late 1990s, a significant difference in survival started to become evident in adolescents with cancer treated in paediatric units compared to those treated in adult units. In the mid-2000s, several international groups analysed differences in survival in adolescents and young adults with lymphoblastic leukaemia treated with adult versus paediatric protocols, demonstrating the superiority of paediatric protocols in terms of overall and event-free survival16–20.

Different movements have emerged worldwide with the aim of closing this gap in survival in adolescents. In 1998, the Adolescents and Young Adult Committee was created in the United States within the Children’s Cancer Group. In Europe, in 2003, the Teenage Cancer Trust was created in the United Kingdom. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE) created a joint Working Group on cancer in 2015, with the aim of raising awareness in paediatric and adult oncologists and haematologists of the need to work collaboratively, improve the knowledge of cancer in adolescents and disseminate adolescent and young adult care standards in Europe21. In Spain, the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátrica (Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology) instituted a Committee on Adolescents in 2011. In addition, in 2018, the first specialised adolescent care units opened in the Community of Madrid.

Thus, an assessment of the advances that have taken place in Spain seems warranted, using as reference the survey on the subject conducted in 201222.

Material and methodsThe same questionnaire that had been sent out in 2012 via email to 40 paediatric haematology and oncology units in Spain was submitted again, except for the portion that addressed the relationship of surveyed paediatric haematology and oncology units with adult haematology and oncology units, which was deemed subjective and of little relevance. The survey was addressed personally to one physician in each of the 42 units of interest. The questionnaire included 16 items arranged in 4 sections (Table 1):

Full survey.

| 1. Up to which age does your paediatric haematology and/or oncology unit manage patients? | Age 0−12 years/age 0−14 years/age 0−16 years/age 0−18 years/age 0−21 years |

| 2. Are there adolescent-specific units in your hospital? | Yes, general unit for adolescents who need admission for a variety of diseasesYes, specific unit for adolescent with blood or solid tumours No, remain to be developed |

| 3. Your unit manages patients with blood and solid tumours: | All managed in the same ward by the same physiciansAll managed in the same ward by different physiciansWe have separate wards and physicians We have 2 completely independent units |

| 4. How many new patients with cancer does your unit manage per year? | <10 new cases/year—10 to 20 new cases/year20 to 40 new cases/year40 to 80 new cases/year>80 new cases/year |

| 5. Of these patients, which percentage is aged 14–18 years? | <5%5% to 10%10% to 20%>20%I don’t know |

| 6. In your hospital, who manages adolescent patients (14−18 years) with blood tumours? | Us. Adult haematologists (who admit patients to our ward)Adult haematologists, but patient is admitted to our ward |

| 7. In your hospital, who manages adolescent patients (14−18 years) with solid tumours? | Us. Adult oncologists (who admit patients to our ward)Adult oncologists, but patient is admitted to our ward |

| 8. In your unit, is there a physician specifically dedicated to the care of adolescents with cancer? | Yes/no |

| 9. In your unit, are there rooms or spaces specifically designed for adolescents with cancer? | Yes/no |

| 10. The psychological support available in your unit is: | A psychologist on staff is exclusively dedicated to oncological patientsA psychologist exclusively dedicated to oncological patients paid by an institution other than our hospital We have access to the mental health services of the hospital, which provides support when we request itNo psychological support is available to our patients |

| 11. Does your unit have a psychologist exclusively dedicated to adolescents with cancer? | Yes/no |

| 12. Does your hospital have a department of clinical oncology (adult care)? | Yes/no |

| 13. Does your hospital have a department of haematology (adult care)? | Yes/no |

| 14. Did you know that the Strategy for Cancer of the National Health System of Spain, ratified in 2018, clearly specifies that children and adolescents with cancer should be preferably managed in paediatric haematology and oncology units by a multidisciplinary team? | No, I was not awareI’ve heard something about itYes, I knew it |

| 15. Does your unit ever admit patients aged more than 18 years newly diagnosed with a typically paediatric tumour? | Yes, alwaysYes, whenever the administration allowsSometimesRarelyNever |

| 16. Once patients have completed treatment and turn 18 years old, what is the usual procedure? | We discharge the patients and refer them to their primary care physicianWe discharge the patients and refer them to the adult oncology or haematology departmentWe do the follow-up, even if they have turned 18 |

The first section of the questionnaire sought general information on the annual incidence of new cases of cancer in the unit, the age range of managed patients and the distribution of patients by type of tumour (solid vs blood) in the unit.

The second section was devoted specifically to adolescents aged 14–18 years: percentage out of the total patients, and environments and staff specifically dedicated to this age group.

The third section focused on the psychological support offered to these patients: whether services were available and specific for adolescents.

The last section assessed the knowledge of National Plan for Cancer and the follow-up of patients after they reached age 18 years.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the data with the statistical software SPSS 26.0.

ResultsIn 2012, a total of 39 hospitals of the 40 addressed by the survey did participate, corresponding to a response rate of 98%. The response rate was similar in 2022: 95% (40 hospitals out of 42).

At present, the percentage of paediatric units that manages patients through age 18 years is 77.5% (5 units managed patients through age 21 years), compared to 35.9% in 2012 (Fig. 1).

In the past, 71.8% (28) units managed patients with both solid and blood tumours with the same staff. At present, this is still the case in 60% of units (24).

In 2012, there were no units specifically dedicated to adolescents with cancer. In 2022, there are 7 hospitals with specific adolescent cancer units, and 8 are in the process of developing such units.

In 2012, only 25.6% (10) of the units managed more than 40 new paediatric cases a year. The percentage of patients aged 14–18 years was less than 10% in 76.9% of the units (30). At present, 35% (12) of the units manage more than 40 new cases per year. The percentage of patients aged 14–18 years was less than 10% in 35% (14) of the units.

When it came to the management of adolescent patients with blood tumours in Spanish hospitals, we found that in the past, only 30.8% (12) of the paediatric haematology and oncology units managed adolescents with blood cancers. In all other hospitals, adolescents were managed in adult haematology units (Fig. 2). When it came to solid tumours, 48.7% (19) of paediatric units managed adolescent patients with solid tumours. At present, 20 paediatric haematology and oncology units (51.3%) manage adolescents with blood cancers, while 85% of solid tumours in adolescents were managed in 34 paediatric units (Fig. 3).

As regards adolescent-specific infrastructure and care staff, in 2012 only 1 paediatric haematology and oncology unit in Spain had a physician specifically dedicated to adolescents with cancer, and only 2 units had some form of environment, room or space specifically designed for adolescents with cancer. At present, 8 units have physicians dedicated to adolescent care and 11 hospitals have specific adolescent environments.

As for the psychosocial care of patients aged 0–18 years with cancer, in 2012 all units had a psychologist to offer care to patients. In 30.5% of hospitals, the psychologists were hospital staff exclusively dedicated to oncological patients, in 51.6% of units, this specialised position was funded by a foundation, and 17.9% of units could access the psychological services of the hospital to provide support on demand. Only 2 paediatric units had a psychologist dedicated specifically to the care of adolescents with cancer. In 2022, one unit reported not having psychological services for the patients, and in the rest the situation has barely changed, with a foundation funding mental health professionals in 60% of cases. In 5 hospitals, the centre had a psychologist specifically dedicated to the care of adolescents with cancer.

The previous survey assessed knowledge of the strategic plan for cancer of the National Health System of 2006. Of the total participants, 20.5% was not aware of the recommendation that adolescent patients be managed in a paediatric haematology and oncology unit, 15.4% had heard something about it and the rest knew about it. Knowledge in this area has improved, and in the current survey only 3 of the 40 respondents did not know of this strategy.

The last items referred to the follow-up of patients once they became adults, and whether paediatric haematology and oncology units accepted patients aged more than 18 years with typical paediatric diagnoses. In this past, 66.7% of units followed up patients past age 18 years. This percentage has increased to up to 82.5%.

However, when it came to newly diagnosed cases, only 12.8% of units routinely accepted patients aged more than 18 years with a new paediatric cancer diagnosis. At present, 17.5% admits these patients routinely and 12.5% admits them if the management of the hospital authorises it.

DiscussionIn recent years, the awareness of the need to provide specialised care to adolescents with cancer has been increasing through the efforts of scientific societies, governmental bodies, the general population and the demands of patients themselves3,23–26.

One of the most recent advances in the United States includes the Blue Ribbon Panel, instituted in 2016, which gathers the efforts of government agencies, industry, health care professionals and patients and has established a pathway to improve and eventually close the existing gap in survival in adolescents compared to children and/or adults with cancer. The proposed pathway involves the implementation of the recommendations of this expert panel, the creation of a network for collaborative work, including promotion of clinical trials, equity in care, research on the biological characteristics of tumours and identification of the optimal approach to the management of this population26.

In Europe, there are marked differences in the availability of specialised services for adolescents between northern and southern countries. The ESMO/SIOPE Working Group recently published the results of a survey of its members, in which 60% of respondents in Northern Europe reported access to specialised adolescent services compared to 45% in Western Europe and a much lower 13% in Southern Europe, which was consistent with the survey at the national level21. The Working Group considered even the percentages in Northern Europe insufficient. In 2015, these two societies joined efforts and created a Working Group to establish standards of care for adolescents with cancer in Europe27.

In Spain, the Committee on Adolescents was formed in 2011 within the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátrica, and its initial goals were as follows: a) to create awareness of the cancer strategy of the National Health System and its recommendations; b) to promote specialised adolescent environments within oncology units; c) to promote coordination with adult haematologists and oncologists; d) to improve psychosocial support in this age group; and e) to facilitate the delivery of information and referral from primary care centres.

Compared to the previous survey, there was greater awareness of the subject and scientific societies and working groups had since collaborated with the health care authorities in developing a new strategy for paediatric and adolescent cancer that improved on the 2006 approach, with the aim of implementing and assessing the guidelines on the organization of care for cancer in childhood and adolescence approved by the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System in the plenary meeting held on November 15, 2018. The measures approved for implementation were: 1) creation in each autonomous community (AC) of a regional care coordination committee for all cases of childhood and adolescent cancer. This committee had to be created and defined according to applicable regulations; 2) centralization of care delivery in paediatric haematology and oncology units. This model involves the designation, in accordance with any applicable regional regulations, of paediatric haematology and oncology units in the autonomous community such that they would manage the necessary patient volume to be able to deliver optimal care. The SIOPE recommends management of at least 30 new cases a year to acquire sufficient experience. Adolescent patients aged up to 18 years should be managed in paediatric units, unless they can access specific adolescent care units. The care of adolescents should be managed jointly by paediatric haematology and oncology specialists and adult oncologists as appropriate based on the type of tumour.

In 2012, the survey revealed not only that 20.5% of respondents was not aware that these recommendations existed, but also that only 36% of paediatric units in Spain accepted patients aged up to 18 years. At present, 7.5% of respondents still do not know the national plan, but 77.5% of adolescents are managed in paediatric or adolescent care units. The most important milestone was the institution in 2018 of the first 4 multidisciplinary adolescent cancer units in Spain, all in the Community of Madrid. As of now, the survey shows that there are a total of 7 operational adolescent units and 8 in the process of being established. These units have been created with the aim of managing adolescents with cancer in adherence to the care standards defined by European oncology societies27 (Table 2).

Minimum essential requirements for adolescent cancer units.

| Multidisciplinary team |

| Clinical trial availability in adolescent cancers |

| Flexibility in terms of age eligibility for access to diagnosis and treatment services |

| Paediatric and adult care specialists with experience in the management of different cancers in adolescents |

| Age-appropriate psychosocial support meeting the needs of adolescents |

| Fertility preservation programmes |

| Late effect follow-up in survivors |

| Transition programmes |

| Access to genetic testing for assessment of predisposition to cancer |

| Genetic counselling. Genetic testing for hereditary cancer syndrome |

| Adolescent-specific palliative care. Age-specific training programmes for staff involved in care |

| Specific training programmes on adolescent cancer care for health care professionals accredited by health care authorities |

The current literature approaches the psychological management of this age group as unique, as the needs of adolescents differ from those of children or adults28,29. The surveys do not demonstrate any clear advances in this field, which is chiefly explained by the lack of psychologists trained in the speciality and/or exclusive allocation of these providers to adolescent care.

Although multiple sources evince that survival improves when adolescents are managed with paediatric care protocols, we must not forget that adolescents are not “big children”, and in this regard, the promotion of adolescent-specific research and clinical trials involving close cooperation between paediatricians and adult care specialists is the cornerstone of future improvements in survival. European initiatives such as the ACCELERATE platform established by the Cancer Drug Development Forum, SIOPE and Innovative Therapies for Children with Cancer European network30 pursue strategies such as reducing the age of inclusion in phase 2 trials to 12 years and participation of adolescents in phase 1 trials in cases in which there could be potential benefits, such as tumours with specific mutations that are a therapeutic target. The SEHOP and its Working Group on adolescents endorse and promote this initiative.

ConclusionWithout question, the efforts in dissemination and the centralization of care in multidisciplinary specialised adolescent care units or, failing that, paediatric units have been the main and most important advance in Spain in the past decade. Much remains to be done in establishing the fundamental pillars of adolescent cancer care, such as psychological support, care delivery by teams specifically trained on and exclusively dedicated to this age group, participation in European working groups, establishment of specific protocols and/or clinical trials, follow-up of survivors and transitional care bridging paediatric and adult care.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.