Enterovirus (EV) infections are common in childhood. They usually cause benign diseases such as herpangina or hand, foot and mouth disease, and are the most frequent cause of lymphocytic meningitis. Occasionally there is an outbreak that includes cases with neurologic involvement that manifests with acute flaccid paralysis and/or rhombencephalic involvement, as occurred in a 2016 outbreak in Catalonia.

Our aim was to describe the cases of the 4 patients admitted to our hospital with neurologic disease secondary to infection by EV between June and December 2016.

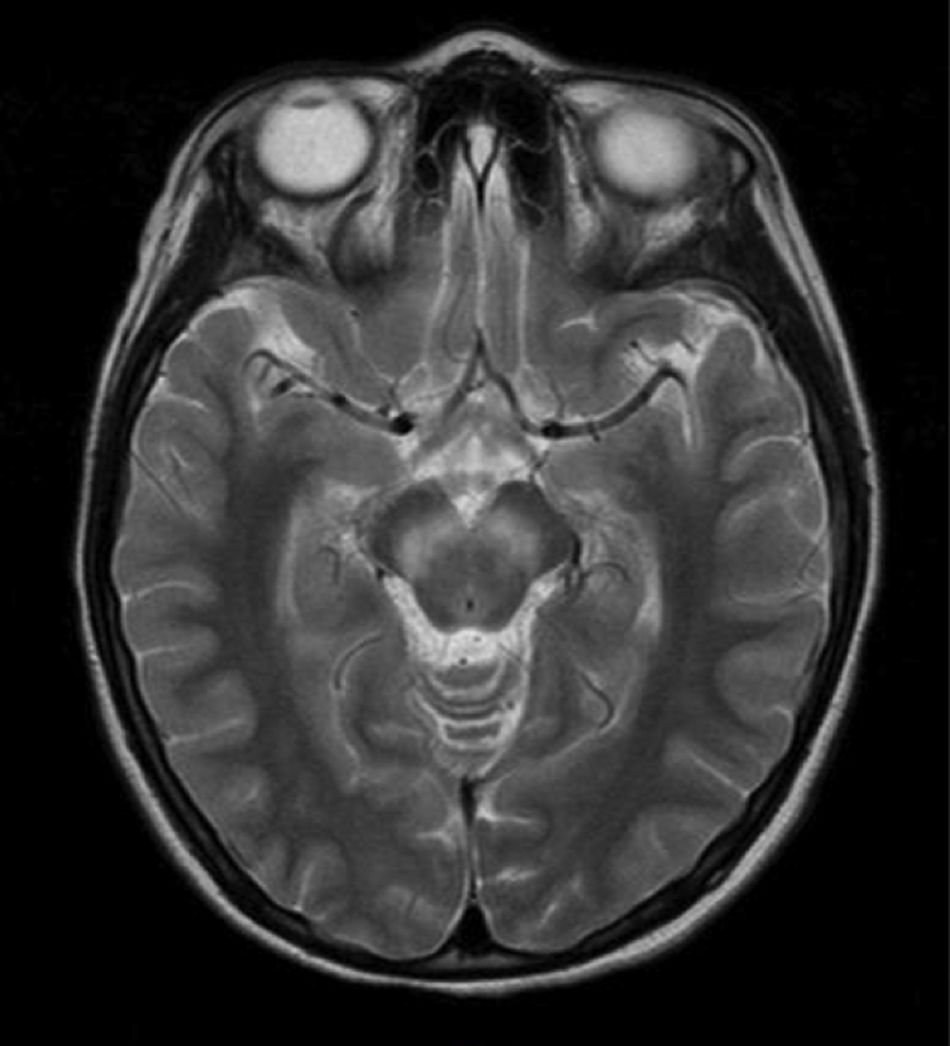

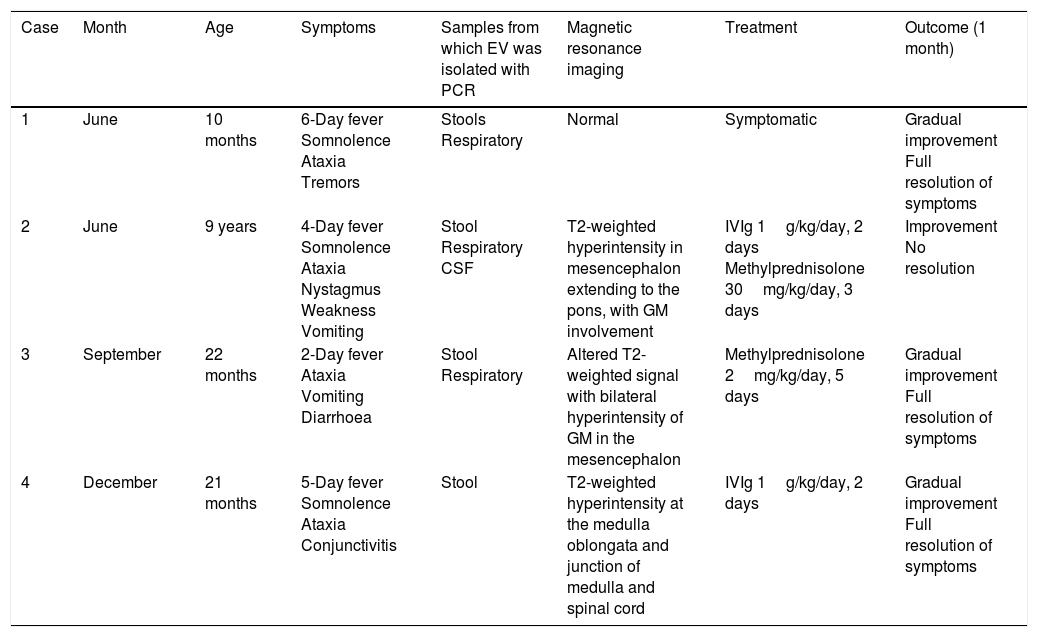

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the patients. At admission, all of them presented with fever of several days’ duration and a constellation of neurologic symptoms that ranged from depression and somnolence to instability, ataxia and involuntary tremors. All patients underwent a lumbar puncture, and microscopic examination of the specimens revealed lymphomononuclear pleocytosis in 3 cases (1, 2 and 3). Testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), respiratory secretion and stool samples by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected EV in at least 1 of the samples in all 4 patients. The virus was detected in the CSF in only 1 case, and in the stool sample in all cases. In 3 of the 4 cases, cranial MRI revealed hyperintense lesions at the level of the rhombencephalon (Fig. 1). When it came to treatment, 2 patients received corticosteroids, 2 intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, and only 1 symptomatic treatment. All patients had favourable outcomes, as they were either asymptomatic or their symptoms had greatly improved compared to admission at the time of discharge.

Main characteristics of cases of acute neurologic disease due to enterovirus.

| Case | Month | Age | Symptoms | Samples from which EV was isolated with PCR | Magnetic resonance imaging | Treatment | Outcome (1 month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | June | 10 months | 6-Day fever Somnolence Ataxia Tremors | Stools Respiratory | Normal | Symptomatic | Gradual improvement Full resolution of symptoms |

| 2 | June | 9 years | 4-Day fever Somnolence Ataxia Nystagmus Weakness Vomiting | Stool Respiratory CSF | T2-weighted hyperintensity in mesencephalon extending to the pons, with GM involvement | IVIg 1g/kg/day, 2 days Methylprednisolone 30mg/kg/day, 3 days | Improvement No resolution |

| 3 | September | 22 months | 2-Day fever Ataxia Vomiting Diarrhoea | Stool Respiratory | Altered T2-weighted signal with bilateral hyperintensity of GM in the mesencephalon | Methylprednisolone 2mg/kg/day, 5 days | Gradual improvement Full resolution of symptoms |

| 4 | December | 21 months | 5-Day fever Somnolence Ataxia Conjunctivitis | Stool | T2-weighted hyperintensity at the medulla oblongata and junction of medulla and spinal cord | IVIg 1g/kg/day, 2 days | Gradual improvement Full resolution of symptoms |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EV, enterovirus; GM, grey matter; IVIg, nonspecific intravenous immunoglobulin therapy; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

In Europe, unlike China, infection by EV serotype 71 had been rare until recently and was associated with fever or hand, food and mouth disease. The virus is transmitted by the faecal–oral route or the oral–oral route. Certain EV serotypes, such as A71, are particularly neurotropic, and it has been hypothesised that neuroinvasion occurs through retrograde axonal transport.1 Starting in March 2016, there were 100 cases in Catalonia that met the case definition criterion of “presentation with rhombencephalic involvement or myelitis with detection of EV.”2 However, isolation of EV is not always associated with neurologic disease, and in fact, one study described that out of a total of 2788 respiratory samples from children with respiratory infections, 148 (5%) corresponded to EV infections, of which only 8 were by the EV-A71 serotype. Among these 8, there was only 1 case with neurologic involvement, which manifested as lymphocytic meningitis; this patient had a favourable outcome.3

In children, the presence of fever and neurologic involvement at the level of the rhombencephalon (myoclonic jerks, tremors and/or ataxia) and/or the medulla oblongata (cranial nerve involvement, abnormalities in swallowing or speech, apnoeic episodes and neurogenic pulmonary oedema)4 should be assessed by examination of the CSF, which usually reveals lymphocytic pleocytosis, and by performance of a MRI exam in the acute stage of disease, whose typical findings are the presence of hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images, especially at the level of the pons, cervical spinal cord, mesencephalon, dentate nucleus and hypothalamus.5

The most sensitive and quick technique to establish the aetiological diagnosis, which is also currently the gold standard, is PCR. Despite the severity of the presentation, detection of EV in the CSF is rare. In fact, in our series only 1 of the 4 patients had a positive result, case 2, a female patient who had more severe neurologic manifestations. Therefore, suspicion of this disease should be approached by the collection of respiratory and stool samples, and detection of enterovirus alone does not suffice to rule out other diseases that may cause acute neurologic symptoms.

Unfortunately, we were unable to perform a serotype analysis of the enteroviruses found in our sample, and therefore, while the clinical and epidemiological data were mainly suggestive of EV-A71, we are unable to state that this was the involved type with certainty.

There is no specific treatment that is effective against infection by EV. Following the guidelines recommended by Spanish scientific societies, patients with severe symptoms received polyvalent immunoglobulins intravenously, as it has been proposed that they have an immunomodulator effect on the release of cytokines involved in the development of severe neurologic symptoms associated with infection by EV, although the evidence on the use of immunoglobulin is scarce and not from randomised controlled trials. Megadose corticosteroid therapy (30mg/kg/day, 3–5 days) has been used in patients with severe neurologic involvement, although its use is not supported by evidence from randomised controlled trials6 and has been extrapolated from previous use in cases of acute myelitis.

Enterovirus A71 spread from the site of its earlier identification in Germany to France and Catalonia,2 causing an outbreak that has not recurred in our province, which suggests that there are environmental and microbiological factors that play a role in the infection rate and virulence that have yet to be identified.

Please cite this article as: Valdivielso Martínez AI, Carazo Gallego B, Cubiles Arilo Z, Moreno-Pérez D, Urda Cardona A. Patología neurológica aguda por enterovirus: revisión de casos clínicos en un hospital andaluz de tercer nivel tras brote epidémico de Cataluña. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89:249–251.