The family structure and parenting are changing in society, sedentary lifestyle, the use of screens and social networks is increasing. Families and health professionals must learn to educate, adapting their health advice to the new social and digital environment.

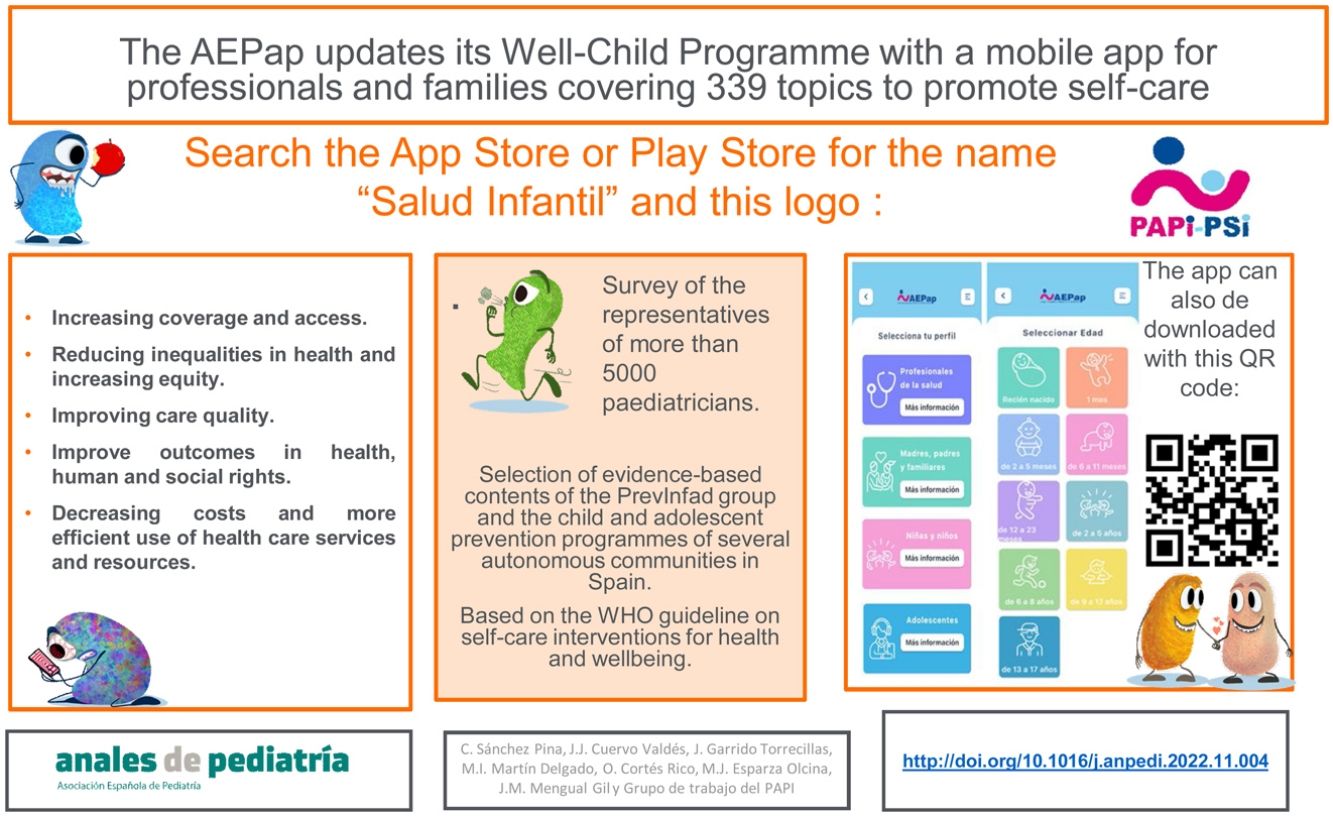

Materials and methodsA survey was sent to the representatives of more than 5000 paediatricians to renew the Well Child Visits Programme of the Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics (AEPap). Contributions from preventive programmes from Andalusia, the Balearic Islands and Asturias were incorporated. The different interventions and advice were distributed in nine age groups.

ResultsPart of the recommendations are based on the work of the PrevInfad group. It uses the methodology of evidence-based medicine and performs the evaluation and synthesis of the evidence in the proposed preventive activities.

The AEPap considers that the Well Child Programme should be carried out by the paediatric team: the paediatrician and the nurse, thus enhancing specific skills.

The WHO considers it essential to empower individuals, families, and communities to optimize their health by making them caretakers of themselves and others, equipping them with tools that protect their well-being.

ConclusionHence, it was decided to capture the Well Child Programme in the format of a free APP for mobile devices, as an innovative and affordable method of disseminating child and adolescent health. Information is given on parenting advice for family members, for children and adolescents and describes health check-ups for health workers.

La estructura familiar y la crianza están cambiando en la sociedad, se incrementa el sedentarismo, el uso de pantallas y de redes sociales. Las familias y los profesionales sanitarios deben aprender a educar, adaptando sus consejos de salud al nuevo entorno social y digital.

Material y métodosPara renovar el Programa de Salud Infantil (PSI) de la Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AEPap) se envió una encuesta a los representantes de más de 5.000 pediatras. Se incorporaron aportaciones de los programas preventivos de Andalucía, Baleares y Asturias. Se distribuyeron las diferentes intervenciones y consejos en nueve grupos etarios.

ResultadosParte de las recomendaciones están basadas en el trabajo del grupo PrevInfad, llevadas a cabo con metodología de medicina basada en la evidencia, mediante la evaluación y síntesis de la evidencia de las actividades preventivas propuestas.

La AEPap considera que el PSI debe realizarse por el equipo de pediatría: pediatra y enfermera/o, potenciándose así las competencias específicas.

La OMS considera primordial empoderar a las personas, familias y comunidades para que optimicen su salud al convertirlas en cuidadoras de sí mismas y de otros, dotándolas de herramientas que protegen el bienestar.

ConclusionesPor todo ello se decide plasmar el PSI en formato de APP para dispositivos móviles gratuita, como método innovador y asequible de divulgación de salud infantojuvenil. Se informa sobre consejos de crianza para los familiares, para los niños/as y adolescentes y describe las revisiones de salud para los sanitarios.

The health care professionals that promote the biopsychosocial health of children and adolescents have witnessed a transformation in lifestyle habits across society in only a few years. The traditional family structure is changing, and there are different models of attachment and parenting1, new dietary trends and an increase in sedentary lifestyles, overweight and obesity in children and adolescents2–8. Means for communicating through screens, mobile phones and social networks are proliferating9,10. Today, there is increasing access, ubiquitous and instantaneous, to any type of information or images at increasingly early ages. Constant interpersonal communication and information are encroaching on our free time and becoming dominant, leading to progressive isolation11.

All these changes can have a positive or negative impact in the biopsychosocial health of the most vulnerable individuals: children and adolescents. Therefore, families need to learn how to educate children on this new reality, and health care professionals have to adapt health guidance to the new social and digital environment of the patients.

There are key subjects that must be addressed, such as promoting positive and consistent parenting, respect, equality, emotional health and healthy sexual development, in addition to setting boundaries for children. It is important to improve stimulation of spoken language, promote adequate screen use and specify when mobile phones can be used. Another essential aspect is the prevention of domestic violence and sexual abuse, as prevention can reduce the probability of abuse by half12. Evidence-based information must be given on novel topics such as the prevention of bullying and cyberbullying, avoiding environmental pollutants and promoting environmental awareness. Ongoing efforts must be made to promote physical activity and healthy dietary habits3,5.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends promoting self-care interventions as critical elements for achieving universal health coverage, promoting health and help vulnerable populations. This allows individuals to have better control of their own health13.

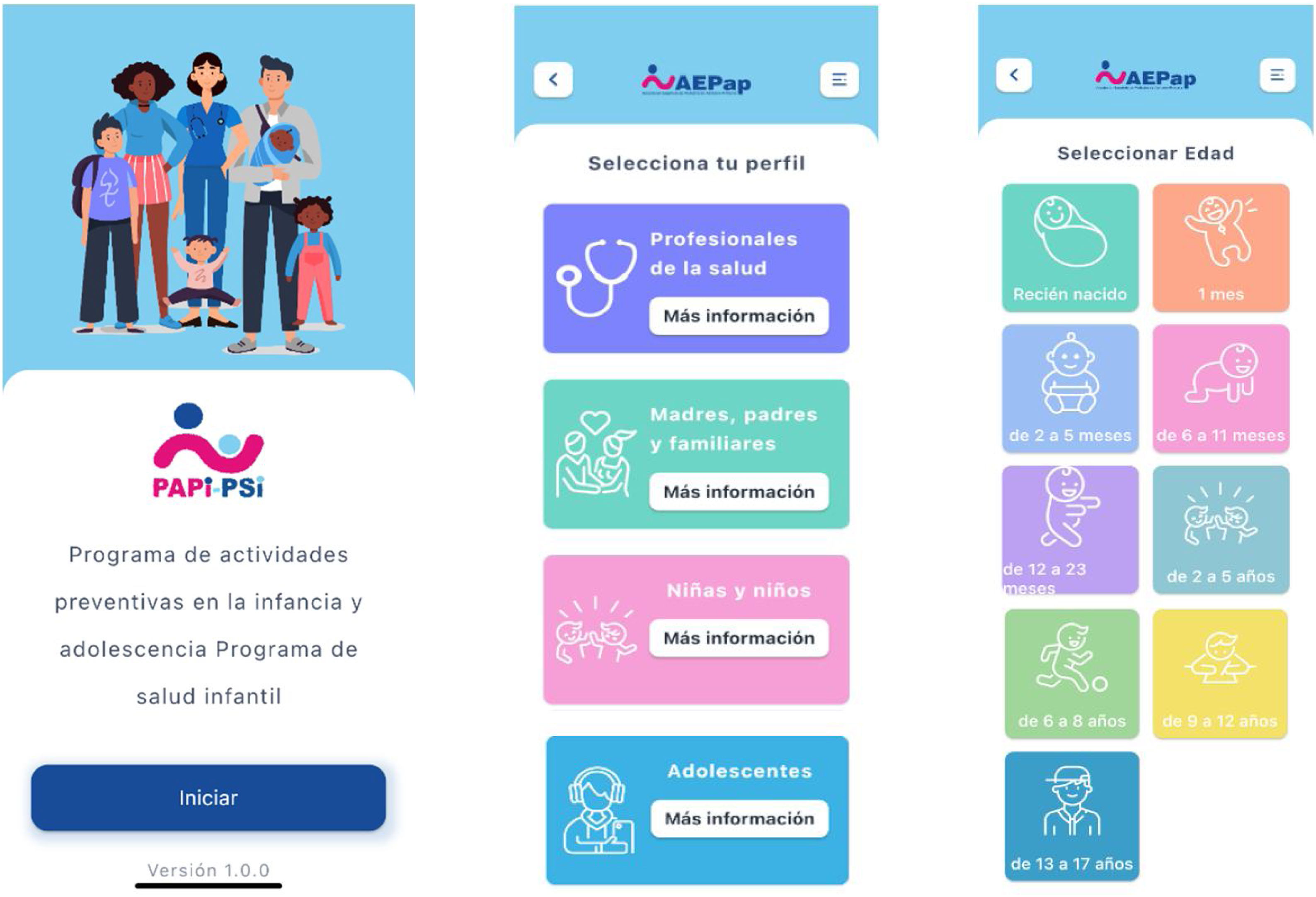

For all the above reasons, the Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics, AEPap) has updated its Well Child Programme (WCP). The new Programme for Preventive Activities in Childhood and Adolescence (known as PAPI, for the Spanish acronym), presented in the form of a mobile application (app), was developed to update and expand the WCP published in 201114 to adapt it to the emerging needs of the population and of the health care professionals that provide services to children and adolescents at the primary care level. The PAPI acronym is also a playful reminder by paediatricians of the need to promote equality in childcare and parenting.

MethodsThe WCP was updated taking into account the contributions of working groups of the AEPap with a particular focus on health guidance and preventive paediatrics. The updates of the WCPs established by various public administration bodies in different autonomous communities in Spain were also reviewed.

The AEPap is an association that represents more than 5000 primary care (PC) paediatricians. In the years it has been operating, it has developed informational tools for the general population, chief of which is the Familia y Salud website that provides health guidance to families and adolescents. This site has had more than 9 003 614 users and received more than 12 785 306 visits15. The following working groups of the AEPap also collaborated in the development of PAPI: health education, social and community paediatrics, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and psychoeducational development, paediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, sleep and PrevInfad (prevention in paediatrics). Experts in childhood vaccination and breastfeeding affiliated with the baby-friendly hospital initiative in Spain (known as IHAN) also participated. These working groups include several experts in paediatrics that are considered leaders in their respective fields at the national level. The PAPI programme has also drawn from the parenting and health guidance contents developed by the Familia y Salud and other materials produced by different working groups of the AEPap.

Within the public health care administration, some primary care management teams have published WCP documents developed in close cooperation with paediatrics associations and societies at the regional level. The AEPap is a federation formed by the PC paediatrics societies of different autonomous communities. At the local level, some of these societies have developed their own WCPs, which were reviewed during the development of PAPI.

To get the PAPI project started, a Google form was submitted in December 2020 to the spokespersons of the board of directors of the regional societies, which represent more than 5000 PC paediatricians. The same form was submitted to the coordinators of the 17 working groups of the AEPap. The form was used to collect information on the different WCP documents developed or updated in the past 5 years and any aspects newly introduced to these programmes.

The programmes used in the development of PAPI were the WCP of Andalusia published in 201416, the programme of the Balearic Islands published in 201817 and the programme of the Principality of Asturias also published in 201818. The new WCP of the Basque Country had not been developed in full at the time19. The Andalusian programme was selected on account of the additional topics it introduced, such as positive and consistent parenting, appropriate screen use, stimulation of speech, reading aloud, promotion of drawing and prevention of sexual abuse20. The programme from the Balearic Islands was selected due to its contributions in health education, as it incorporated 2 workshops for parents: one on positive parenting21 and one for health education22. The programme from Asturias was selected due to its coverage of social and community paediatrics.

We distributed the different interventions into 9 age groups, based on the volume of specific information available, with a larger number of topics in the first year of life, when families and providers alike tend to have more questions and concerns (Table 1: age groups).

Evidence-based recommendationsPart of the recommendations of the PAPI programme and regional WCPs are based on the work carried out PrevInfad, a working group of paediatricians that was formed in 1990, originating in the childhood and adolescence group within the Programme of Preventive Activities and Health Promotion (PAPPS) of the Sociedad Española de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria (Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine, SEMFYC), and which has been a working group of the AEPap since year 2000.

The PrevInfad assesses and summarises the evidence for each of the prevention activities it proposes, which can be consulted at: https://previnfad.aepap.org.

PrevInfad uses the approach of evidence-based medicine to develop its recommendations (Table 2), and the method used in their development has been published in its working manual23. It grades its recommendations either with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) or the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) system, depending on the subject matter.

Evidence-based medicine approach applied in the development of the recommendations.

| Framing the question |

| Literature search and selection of evidence |

| Evaluation and synthesis of evidence |

| Statistical methods used to measure results |

| Magnitude of benefit |

| Magnitude of harm |

| Applicability |

| Development of recommendations |

A work manual is available at https://previnfad.aepap.org/manual-de-trabajo23.

We selected some of the interventions recommended by the PrevInfad working group in Spain in addition to those of other institutions, such as the USPSTF, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States and the WHO, synthesising the evidence for the supporting recommendations for childhood preventive interventions for primary health care endorsed by the WHO24,25.

Results and discussionIn the synthesis of the evidence published by the WHO, the authors found a high degree of consensus between international institutions regarding the effectiveness of the single interventions of administering vitamin D and topical fluoride through oral hygiene. Consensus was more variable for the multiple interventions described to prevent sudden infant death syndrome and the prevention of unintentional injuries, as evidence of their effectiveness is harder to ascertain. Institutions generally agreed in recommending vision screening based on age and recommending against universal screening for language and speech delay and iron deficiency, they had some differences for pulse oximetry and autism24.

Table 3 summarises the recommendations regarding screening, prophylaxis or health guidance in the field of PC paediatrics developed by PrevInfad, along with their grading based on the quality of the evidence; for some interventions, there was sufficient evidence to support their implementation, for others, there were some questions, and for yet others the evidence supported a recommendation against their implementation26,27.

Summary of the PrevInfad recommendations, 2022 update https://previnfad.aepap.org/.

| PREVINFAD recommendations | Recommendation grading method | |

|---|---|---|

| USPSTF | GRADE | |

| Screening | ||

| Vision screening at 3−5 years | B | |

| Vision screening at 6−14 years | I | |

| Universal coeliac disease screening | Weak against | |

| Risk group coeliac disease screening | Strong in favour | |

| Universal chlamydia screening in sexually active adolescents | I | |

| Chlamydia screening in adolescents engaging in sexual risk behaviours | B | |

| Cryptorchidism | B | |

| Major depression | D | |

| Scoliosis | Weak against | |

| Universal screening for iron-deficiency anaemia | Strong against | |

| Risk group screening for iron-deficiency anaemia | Weak in favour | |

| Risk group screening for high cholesterol | I | |

| Hypertension | I | |

| Hearing loss (newborn hearing screen) | Weak in favour | |

| Universal autism spectrum disorder screening | Weak against | |

| Risk group autism spectrum disorder screening | Strong in favour | |

| Universal developmental disorder screening | Weak against | |

| Developmental disorder screening if there is clinical suspicion | Weak in favour | |

| Universal tuberculosis screening | Strong against | |

| Risk group tuberculosis screening | Strong in favour | |

| Prophylaxis | ||

| Vitamin D in infants under 1year | B | |

| Vitamin D in children aged >1year in risk groups | B | |

| Vitamin D in preterm infants under 1year | A | |

| Vitamin K for prophylaxis of VKDB of the newborn | Strong in favour | |

| Iodine supplementation during pregnancy and breastfeeding | Weak against | |

| Guidance | ||

| Physical activity and sports | Weak in favour | |

| Breastfeeding support | Strong in favour | |

| High cholesterol | B | |

| Prevention of hypertension | A | |

| Prevention of smoking in adolescents | Strong in favour | |

| Prevention of unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases in adolescents | B | |

| Prevention of unintentional injury at home in children | B | |

| Prevention of road traffic injuries in children | B | |

| Prevention of sudden infant death syndrome | A | |

| Prevention of sudden infant death syndrome | B | |

| Prenatal care | A | |

VKDB: vitamin K deficiency bleeding, USPSTF: US Preventive Task Force. Available in: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions. GRADE metodología GRADE. Available in: https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/.

Recommendation grading categories of the USPSTF 2012.

The USPSTF has defined 5 grades to assign to recommendations.

A - There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.

B - There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

C - Fair evidence that there is likely to be only a small benefit from this service.

D - There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.

I - Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

Assessment of recommendations with the GRADE method:

a. Use recommended – Strong in favour.

b. Use suggested – Weak in favour.

c. Use recommended against – Strong against.

d. Use discouraged – Weak against.

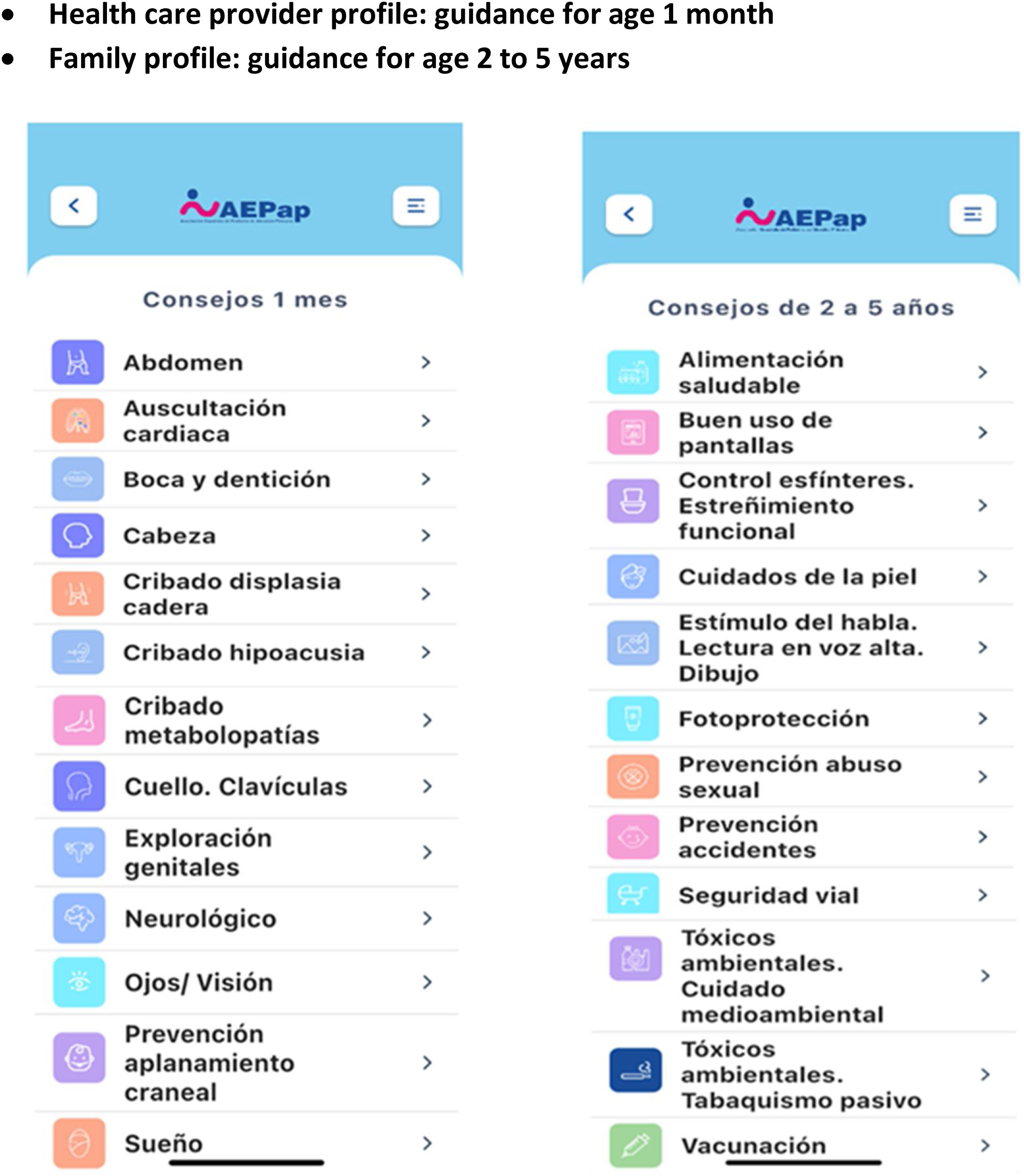

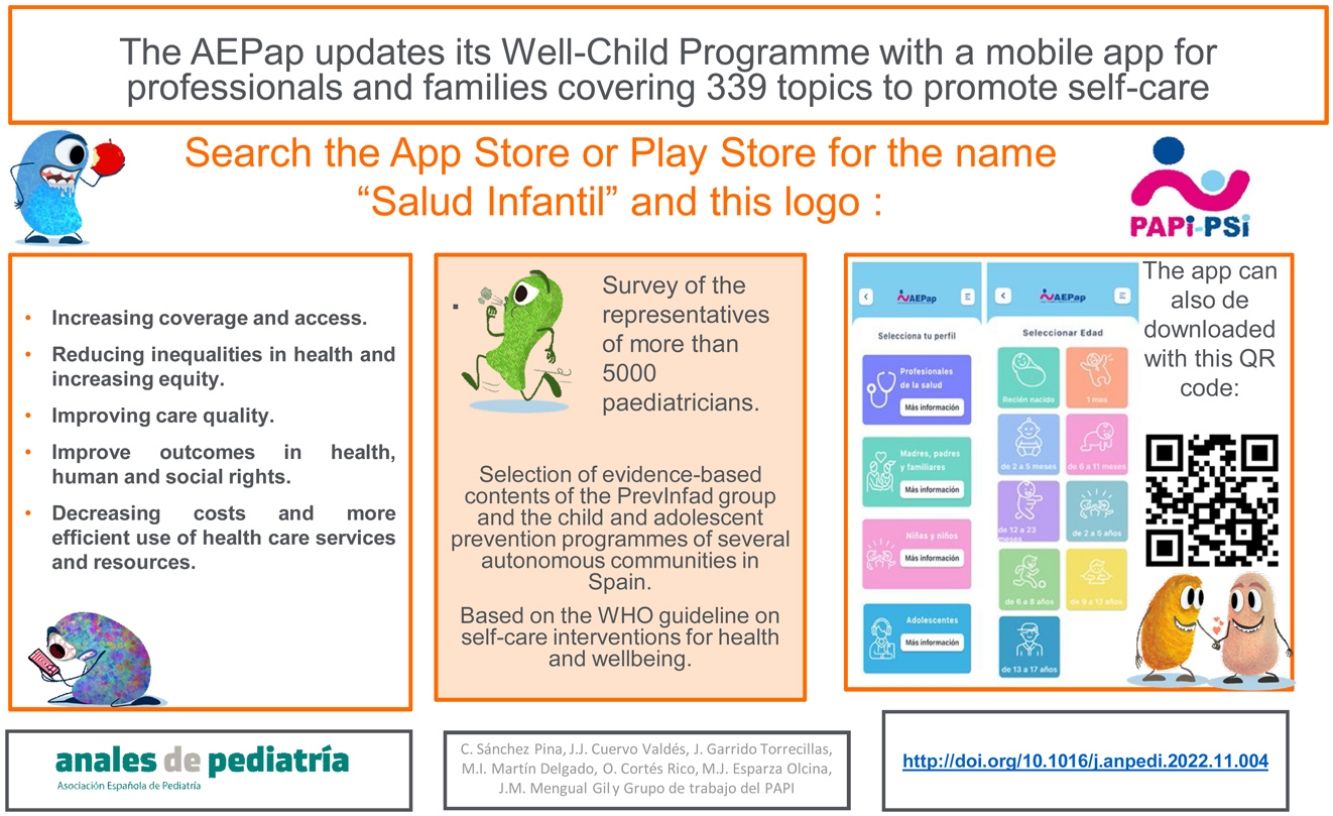

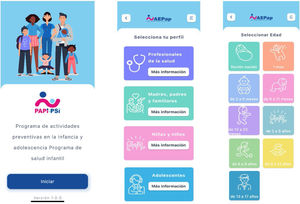

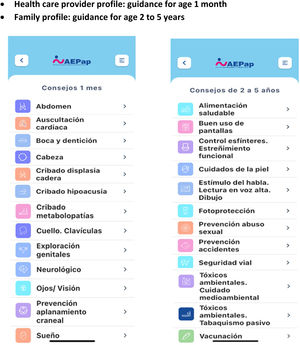

The PAPI application covers a total of 339 topics on child and adolescent care, broken down into 9 age groups that range from the neonatal period to age 13−17 years. There are 194 topics offering guidance for family members on a variety of issues, 31 topics for older children and adolescents and 114 topics for paediatric care providers. The topics are summarised, presenting a selection of the most useful advice in a user-friendly format. For topics for which there was insufficient scientific evidence, the contents were written by paediatric care experts that are leaders in Spain on the subjects of vaccination, nutrition, social paediatrics, ADHD, members of the team of the Familia y Salud website and members of the working group on health education. Topics related to breastfeeding were written by paediatricians members of the baby-friendly hospital initiative in Spain (IHAN).

The AEPap considers that the WCP must be implemented by the paediatric care team: the paediatrician and nurse, ideally, a paediatric nurse28,29. Organic Law 8/2015 of 22 July on the amendment of the child and adolescent protection system advocates for guaranteeing protection for minors consistently throughout the state and develops on and reinforces right of minors to have their best interests upheld, a fundamental principle in this field30,31. In spite of these, there are regions, such as the autonomous community of Andalusia or certain areas of Madrid, that do not have specific clinics nor paediatric nurses specifically allocated to provide these services32,33.

The role of nurses in monitoring growth, visual acuity, hearing, development and other aspects, administering vaccines and offering guidance in health prevention and promotion complements the work of physicians specialised in paediatric care. The paediatrician is the specific provider responsible to carry out full physical examinations, prescribe the vaccines appropriate for each age, order diagnostic tests and prescribe any medication needed by the patient. A full physical examination by the paediatrician is not necessary in every scheduled well-child visit, as suggested in Table 4.

Children and adolescents will receive better care from the paediatric care team at the primary care centre if physicians and nurses work in tandem and on a 1:1 ratio34. At least one of each of these professionals, a paediatrician and a nurse, must be allocated to each caseload so that the specific competencies that fall in the scope of each of these professionals are best utilised in each programmed well-child visit35. This would make it possible to assess for adequate growth and development, review the vaccination schedule, provide up-to-date health recommendations and revise prescriptions upon the early detection of changes in health to deliver prompt and appropriate treatment in a single visit.

Within the framework of PAPI, the AEPap proposes that WCP activities should be carried out in specialised paediatric clinics, with waiting areas separate from those of adults and designed to be more welcoming to young patients.

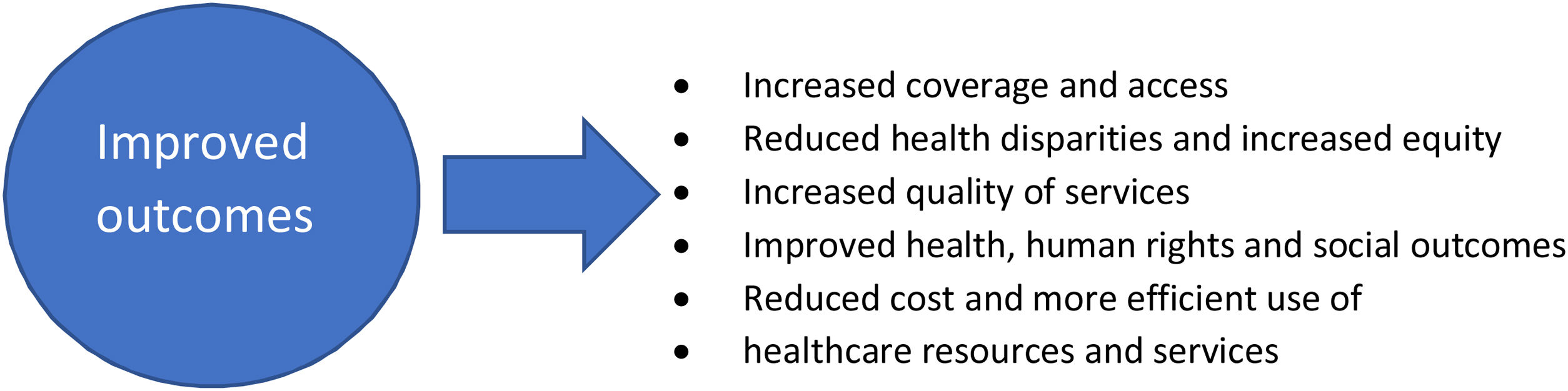

The WHO considers it essential to empower individuals, families and communities to improve their own health by enabling them to care for themselves and others and providing tools to protect wellbeing. Health promotion encompasses a broad range of social and environmental interventions aimed at improving and protecting the quality of life of all individuals13.

For all of the above, the decision was made to present the PAPI as a free mobile application as a novel means for disseminating information about child and adolescent health. This mobile app offers guidance on parenting for families, healthy lifestyle recommendations for children and adolescents and information on how to carry out WCP checkups in each specific age group for health care professionals in paediatric PC teams (Fig. 1: main screens of the app).

The three main elements of primary healthcare described in the 2018 Declaration of Astana are13:

- 1

Meeting people’s needs through comprehensive and integrated health services (including promotive, protective, preventive), prioritizing primary care and essential public health functions;

- 2

Systematically addressing the broader determinants of health (including social, economic and environmental factors as well as individual characteristics and behaviours); and

- 3

Empowering individuals, families and communities to optimize their health as advocates of policies that promote and protect health and well-being, as codevelopers of health and social services and as self-carers and caregivers (Fig. 2: WHO guideline on self-care interventions).

Figure 2.WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being, 2022 revision: executive summary.

WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being, 2022 revision: executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available in: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1438249/retrieve.

Self-care interventions give individuals more choice and improve individual autonomy when they are accessible, appropriate and affordable. These interventions are significant drivers of self-determination, self-efficacy, autonomy and active participation in their own health in both self-carers and caregivers13.

In its good practice statements, the WHO declares that “All self-care interventions for health must be accompanied by accurate, understandable and actionable information, in accessible formats and languages, about the intervention itself and how to link to relevant community- or facility-based healthcare services, and the opportunity to interact with a health worker or a trained peer supporter to support decisions around, and the use of, the intervention”. Ideally, the paediatrician and/or the nurse will provide guidance during routine checkups, thus personalising the contents covered by the app for each child or adolescent13.

The time allocated to provide health guidance and the multiple current recommendations is never sufficient in the overcrowded primary care centres in Spain. The aim in using the novel mobile application format is to extend the time that families can access parenting guidance developed by paediatricians who are leaders in their respective fields in Spain, for the purpose of promoting and prolonging personalised intensive interventions. Individual or group intensive interventions (multiple sessions lasting 30min or longer) have been found to achieve better short- and long-term outcomes compared to short- and intermediate-length interventions36.

The AEPap decided to design the programme as a mobile app to facilitate and improve the delivery of information on disease prevention, and to make it free to the public to provide unlimited access to parenting advice developed by PC paediatricians to every family. This is a modern, manageable, structured and dynamic format chosen with the aim of empowering parents by delivering all contents relevant to the health of their children through a simple QR code used to download the app, with no administrative red tape.

The application is a tool meant to palliate the lack of time and scarcity of human resources of primary care centres, consolidating the health recommendations of different revisions of the WCP by age group. Thus, families will be able to consult the recommendations whenever they need, at home or prior to attending a scheduled well-child visit with the child to be able to ask any questions they may have about them (Fig. 3: Examples of topics in the app).

The AEPap hopes that this new tool will prove useful to both providers and families. The app is called “Salud Infantil” (paediatric health) and has been available for download to mobile devices since September 2022 in the App Store and the Play Store. It can also be downloaded through a QR code (Fig. 4: How to download the app).

FundingThe study did not receive any funding from the public, private or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Marta Esther Vázquez Fernández, Catalina Núñez Jiménez, Ana Fierro Urturi, Cristina García de Ribera, Elena Santamaría Marcos, Fátima Muñoz Velasco, Margarita Escudero Lirio, María Alfaro González, María José García Mérida, María Tríguez García, María Rosa Pavo García, M.ª Esther Serrano Poveda, Elena Fernández Segura, Nieves Nieto del Rincón, Carolina Hernández-Carrillo Rodríguez, Ana María Lorente García Mauriño, Paloma de la Calle Tejerina, Ana Garach Gómez, Teresa Cenarro Guerrero, Juan Rodríguez Delgado, Esther Ruíz Chércoles, Laura García Soto, José María Mengual Gil, Julia Colomer Revuelta, Olga Cortés Rico, María Jesús Esparza Olcina, José Galve Sánchez-Ventura, Ana Gallego Iborra, José Ignacio Pérez Candás, Ángel Carrasco Sanz, María de los Ángeles Ordóñez Alonso, Narcisa Palomino Urda, Manuela Sánchez Echenique, Ignacio Cruz Navarro, Clara García Cendón, Judith Montañez Arteaga, Gema Perera de León, José Miguel García Cruz, Rufino Hergueta Lendínez, Cecilia Matilde Gómez Málaga, Francisco Javier Soriano Faura, Lourdes Aguilera López, Edurne Ciriza Barea, Francisco Javier Navarro Quesada, Ángel Hernández Merino, José Murcia García, Mireia Cortada Gracia, Ramón Ugarte Líbano.