Violence is a public health problem, and when it affects childhood, it can cause illness throughout the individual’s life. Apart from being able to cause damage in the physical, mental and social spheres, it represents a violation of the rights of the affected children, and a high consumption of resources, both economic and social.

A multitude of investigations have improved attention to this violence. However, these advances are not consistent with the practical management of victims, both in Primary and Hospital Care. There is a significant area of improvement for paediatric care.

Through this article, different professionals from all established paediatric health care facilities develop general lines of knowledge and action regarding violence against children. An overview is taken of the legislation related to childhood, the different types of abuse that exist, their effects, management and prevention. It concludes with an epilogue, through which we aim to move sensibilities.

In summary, this work aims to promote the training and awareness of all professionals specialized in children’s health, so that they pursue the goal of achieving their patients’ greatest potential in life, and in this way, to help create a healthier society, with less disease, and more justice.

La violencia es un problema de salud pública. Esta, cuando afecta a la infancia, puede generar enfermedad a lo largo de toda la vida del individuo. Aparte de poder producir daños en la esfera física, psíquica y social, supone una vulneración de los derechos de los niños afectados y un elevado consumo de recursos tanto económicos como sociales.

Multitud de investigaciones han mejorado la atención a esta violencia. Sin embargo, estos avances no son parejos con el manejo práctico que se realiza a las víctimas tanto en la atención primaria como en la hospitalaria. Existe una significativa área de mejora para la atención pediátrica.

A través de este artículo, distintos profesionales de todas las áreas sanitarias pediátricas establecidas desarrollan líneas generales de conocimiento y actuación con respecto a la violencia contra la infancia. Se hace un recorrido a través de la legislación relacionada con la infancia, las distintas tipologías de maltrato que existen, sus efectos, manejo y prevención. Concluye con un epílogo, a través del cual pretendemos mover sensibilidades.

En resumen, este es un trabajo que pretende fomentar la formación y sensibilización de todos los profesionales especializados en la salud infantil, para que persigan como objetivo el que sus pacientes alcancen su mayor potencial en la vida y, de esa manera, ayudar a crear una sociedad más sana, con menos enfermedad y más justa.

In 1883, the Spanish translation of the Étude médico-légale sur l’infanticide (“Estudio médico-legal sobre el Infanticidio”), a forensic study on infanticide by Auguste Ambroise Tardieu, was published in Spain. It was the first published work devoted to the abuse suffered by children. Later, in the mid-20th century, a theoretical framework on the subject of child abuse started to be developed. Authors like Caffey, Evans, Silverman and, most decisively, Henry Kempe established the scientific basis of a problem that had until then been perceived as concerning exclusively the family and society spheres and, in extreme cases, required the involvement of incipient welfare services. At the same time, the first efforts to protect children and adolescents started to emerge. Pioneers like Concepción Arenal in Spain, a revolutionary spirit ahead of her time, or Mary Ellen Wilson in the United States paved the way for the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), an international treaty promulgated by the United Nations and ratified by Spain in 1990, in which the definition of “child” was any individual aged less than 18 years. It is based on four fundamental principles regarding the rights of minors: non-discrimination, the best interests of the child, the right to life, survival and development and respecting the views of the child in all matters affecting the child.

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared violence a public health problem. Subsequent definitions added to the physical, psychological and social damage the violation of the human rights of the victim and the power and control exerted by the perpetrator on the victim. Violence has consequences that manifest in the short, medium and long term. It not only causes pain and injury to the individual, but also has a social impact and has substantial economic costs. Preventing violence is highly beneficial, not only from an economic standpoint, for society as a whole.1

In recent years, the scientific evidence on child abuse has continued to grow, and new and significant concepts have emerged. These include the impact of adverse as well as positive childhood experiences, trauma-informed care, allostasis and allostatic load or toxic stress, among others,2 which have contributed significantly to the development of a new comprehensive care model for abused minors.

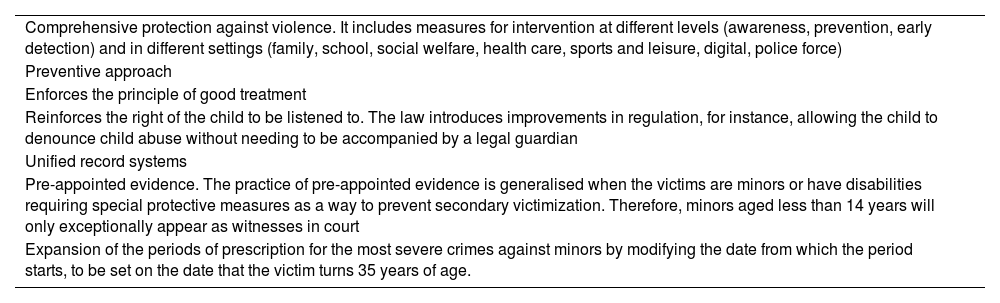

Legal frameworkThe legislation concerning the care of minors is extensive both at the regional, national and international level. The knowledge of health care professionals on this legislation tends to be poor.3 In Spain, at the national level, the changes introduced in 2015 with Organic Law 8/2015 and Organic Law 26/2015 amending the child and adolescent protection system, constituted a significant advance in child welfare. They were followed 6 years later by the promulgation of the Organic Law on the Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents against Violence (commonly referred to as LOPIVI, its acronym in Spanish). Table 1 presents the key changes introduced by this law. Organic Law 10/2023 on the comprehensive guarantee of sexual freedom includes specific measures to guarantee the protection of children and adolescents from sexual abuse and eliminates the distinction between sexual assault and sexual abuse, so that the latter term is thereby rendered obsolete. It considers any behaviour that violates sexual freedom and without express consent from the other person as sexual assault.

Changes introduced by Organic Law 8/2021, on the comprehensive protection of children and adolescents against violence.

| Comprehensive protection against violence. It includes measures for intervention at different levels (awareness, prevention, early detection) and in different settings (family, school, social welfare, health care, sports and leisure, digital, police force) |

| Preventive approach |

| Enforces the principle of good treatment |

| Reinforces the right of the child to be listened to. The law introduces improvements in regulation, for instance, allowing the child to denounce child abuse without needing to be accompanied by a legal guardian |

| Unified record systems |

| Pre-appointed evidence. The practice of pre-appointed evidence is generalised when the victims are minors or have disabilities requiring special protective measures as a way to prevent secondary victimization. Therefore, minors aged less than 14 years will only exceptionally appear as witnesses in court |

| Expansion of the periods of prescription for the most severe crimes against minors by modifying the date from which the period starts, to be set on the date that the victim turns 35 years of age. |

At the international level, the CRC is the supreme law in regard to the recognition of the child as a holder of rights. Article 3.3 of the Treaty on European Union establishes the protection of the rights of the child as one of the aims of the union, further expanded on in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, the European Convention on Human Rights, the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (Lanzarote Convention) and the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights.4

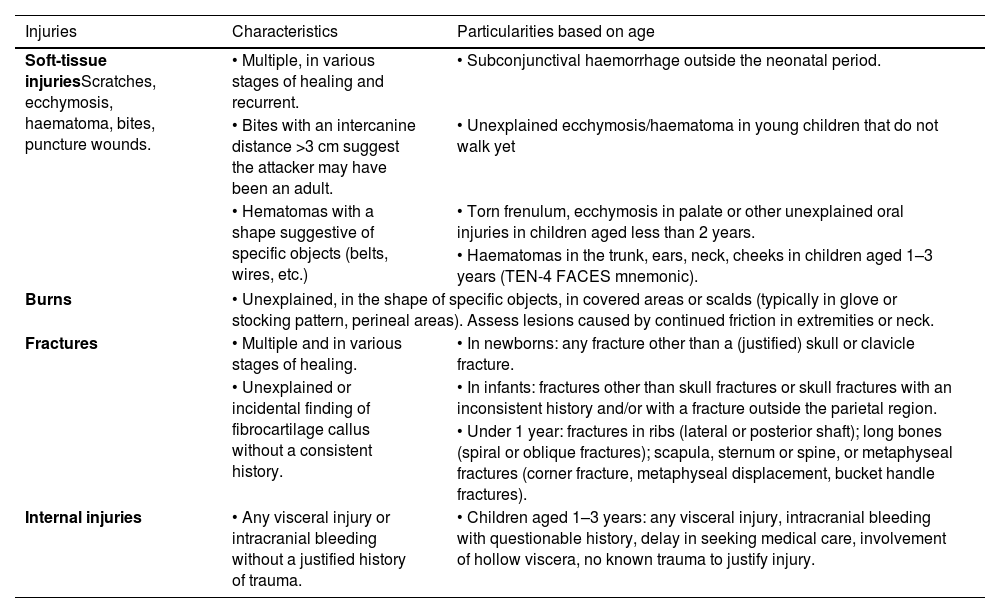

Types of abuseThere are four recognised types of child abuse. The most frequent type is neglect, in which the basic needs of the child or adolescent (nutrition, clothing, hygiene, health care, protection, education, emotional needs, etc.) are not being fulfilled by their primary caregivers. In 2021, neglect accounted for 76% of reported cases of child abuse in the United States5 and 42.75% of cases recorded in the Unified Register of Child Abuse (known as RUMI) in Spain,6 which has since been replaced by the Unified Register of Welfare Services concerning Violence against Children (RUSSVI). We ought to highlight that child abuse reports are least frequently filed from health care settings, although there has been a mild increase in frequency in recent years. Of all reports recorded in RUMI, 30.75 % were for psychological or emotional abuse, which occurs when the primary caregivers of children or adolescents make them feel unloved, unheard, unappreciated, unsafe or rejected. In spite of being the most frequent forms of child abuse, neglect and psychological/emotional abuse tend to be harder to identify, address and manage, and are often the forms of abuse that generate the most uncertainty in paediatric health care professionals. Physical abuse accounted for 16.91% of cases, and it is defined as any nonaccidental behaviour of the parents or caregivers that constitutes a risk of or causes physical injury or disease in a child or adolescent. Lack of training and awareness regarding child abuse frequently leads to the misconception that physical abuse is the only type of abuse that can be exerted against minors. In most cases of physical or psychological/emotional abuse, a medical visit is not made expressly for this reason, and it is the skill, knowledge, experience and awareness of health care professionals that allows its detection. In the case of children aged less than 2 years, sentinel injuries have been described that could be associated with child abuse (Table 2).

Sentinel injuries suggestive of physical abuse.

| Injuries | Characteristics | Particularities based on age |

|---|---|---|

| Soft-tissue injuriesScratches, ecchymosis, haematoma, bites, puncture wounds. | • Multiple, in various stages of healing and recurrent. | • Subconjunctival haemorrhage outside the neonatal period. |

| • Bites with an intercanine distance >3 cm suggest the attacker may have been an adult. | • Unexplained ecchymosis/haematoma in young children that do not walk yet | |

| • Hematomas with a shape suggestive of specific objects (belts, wires, etc.) | • Torn frenulum, ecchymosis in palate or other unexplained oral injuries in children aged less than 2 years. | |

| • Haematomas in the trunk, ears, neck, cheeks in children aged 1–3 years (TEN-4 FACES mnemonic). | ||

| Burns | • Unexplained, in the shape of specific objects, in covered areas or scalds (typically in glove or stocking pattern, perineal areas). Assess lesions caused by continued friction in extremities or neck. | |

| Fractures | • Multiple and in various stages of healing. | • In newborns: any fracture other than a (justified) skull or clavicle fracture. |

| • Unexplained or incidental finding of fibrocartilage callus without a consistent history. | • In infants: fractures other than skull fractures or skull fractures with an inconsistent history and/or with a fracture outside the parietal region. | |

| • Under 1 year: fractures in ribs (lateral or posterior shaft); long bones (spiral or oblique fractures); scapula, sternum or spine, or metaphyseal fractures (corner fracture, metaphyseal displacement, bucket handle fractures). | ||

| Internal injuries | • Any visceral injury or intracranial bleeding without a justified history of trauma. | • Children aged 1–3 years: any visceral injury, intracranial bleeding with questionable history, delay in seeking medical care, involvement of hollow viscera, no known trauma to justify injury. |

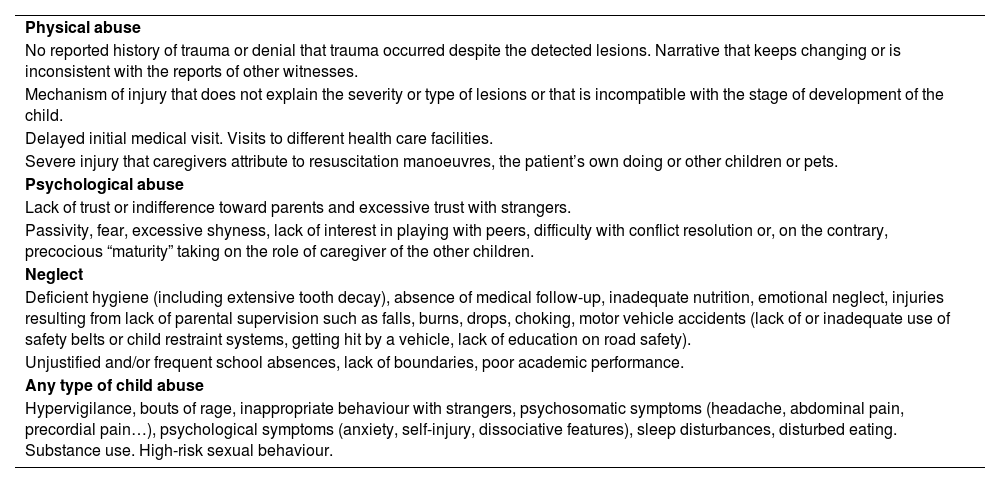

During medical visits, providers can identify warning signs leading to suspicion of violence against children7 (Table 3). We ought to mention the improvement in the diagnosis of bone lesions with the appropriate combination of radiography, magnetic resonance and bone scintigraphy.8

Warning signs suggestive of physical abuse, psychological abuse or neglect.

| Physical abuse |

| No reported history of trauma or denial that trauma occurred despite the detected lesions. Narrative that keeps changing or is inconsistent with the reports of other witnesses. |

| Mechanism of injury that does not explain the severity or type of lesions or that is incompatible with the stage of development of the child. |

| Delayed initial medical visit. Visits to different health care facilities. |

| Severe injury that caregivers attribute to resuscitation manoeuvres, the patient’s own doing or other children or pets. |

| Psychological abuse |

| Lack of trust or indifference toward parents and excessive trust with strangers. |

| Passivity, fear, excessive shyness, lack of interest in playing with peers, difficulty with conflict resolution or, on the contrary, precocious “maturity” taking on the role of caregiver of the other children. |

| Neglect |

| Deficient hygiene (including extensive tooth decay), absence of medical follow-up, inadequate nutrition, emotional neglect, injuries resulting from lack of parental supervision such as falls, burns, drops, choking, motor vehicle accidents (lack of or inadequate use of safety belts or child restraint systems, getting hit by a vehicle, lack of education on road safety). |

| Unjustified and/or frequent school absences, lack of boundaries, poor academic performance. |

| Any type of child abuse |

| Hypervigilance, bouts of rage, inappropriate behaviour with strangers, psychosomatic symptoms (headache, abdominal pain, precordial pain…), psychological symptoms (anxiety, self-injury, dissociative features), sleep disturbances, disturbed eating. Substance use. High-risk sexual behaviour. |

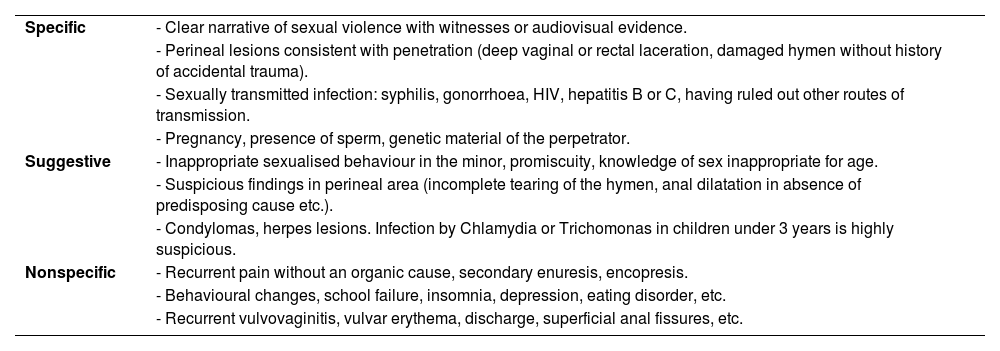

Sexual violence against children (SVC), which amounts to 9.59% of child abuse cases recorded in the RUMI register, is defined on the imposition of activities of a sexual nature by an adult to a minor under 18 years through coercion, which may or may not involve physical contact. The definition also includes any activity of a sexual nature between an adult and minor aged less than 16 years even if the latter consents to it, as in Spain the law sets the minimum age for sexual consent at 16 years. It also includes sexual activity between minors if there is an obvious disparity in physical or psychological development between the victim and the perpetrator or if, in parties of similar age and maturity, force, threats or other means are used to coerce the victim. Current legislation in Spain considers lawful sexual behaviour between minors aged less than 16 years of similar age and physical and psychological development that consent freely to it. In cases of SVC, there are usually no abnormal findings in the physical examination9 and/or diagnostic tests that could be clearly associated with SVC, and it is the report of the victim or of individuals in the victim’s immediate environment that allows its suspicion and/or confirmation (Table 4). Therefore, it is important that all health care professionals know how to manage SVC correctly, with an emphasis on avoiding secondary victimization through inappropriate professional interventions that, in addition to being potentially deleterious to the protection and healthy development of the victim could also hinder the legal process.

Evidence suggestive of sexual violence.

| Specific | - Clear narrative of sexual violence with witnesses or audiovisual evidence. |

| - Perineal lesions consistent with penetration (deep vaginal or rectal laceration, damaged hymen without history of accidental trauma). | |

| - Sexually transmitted infection: syphilis, gonorrhoea, HIV, hepatitis B or C, having ruled out other routes of transmission. | |

| - Pregnancy, presence of sperm, genetic material of the perpetrator. | |

| Suggestive | - Inappropriate sexualised behaviour in the minor, promiscuity, knowledge of sex inappropriate for age. |

| - Suspicious findings in perineal area (incomplete tearing of the hymen, anal dilatation in absence of predisposing cause etc.). | |

| - Condylomas, herpes lesions. Infection by Chlamydia or Trichomonas in children under 3 years is highly suspicious. | |

| Nonspecific | - Recurrent pain without an organic cause, secondary enuresis, encopresis. |

| - Behavioural changes, school failure, insomnia, depression, eating disorder, etc. | |

| - Recurrent vulvovaginitis, vulvar erythema, discharge, superficial anal fissures, etc. |

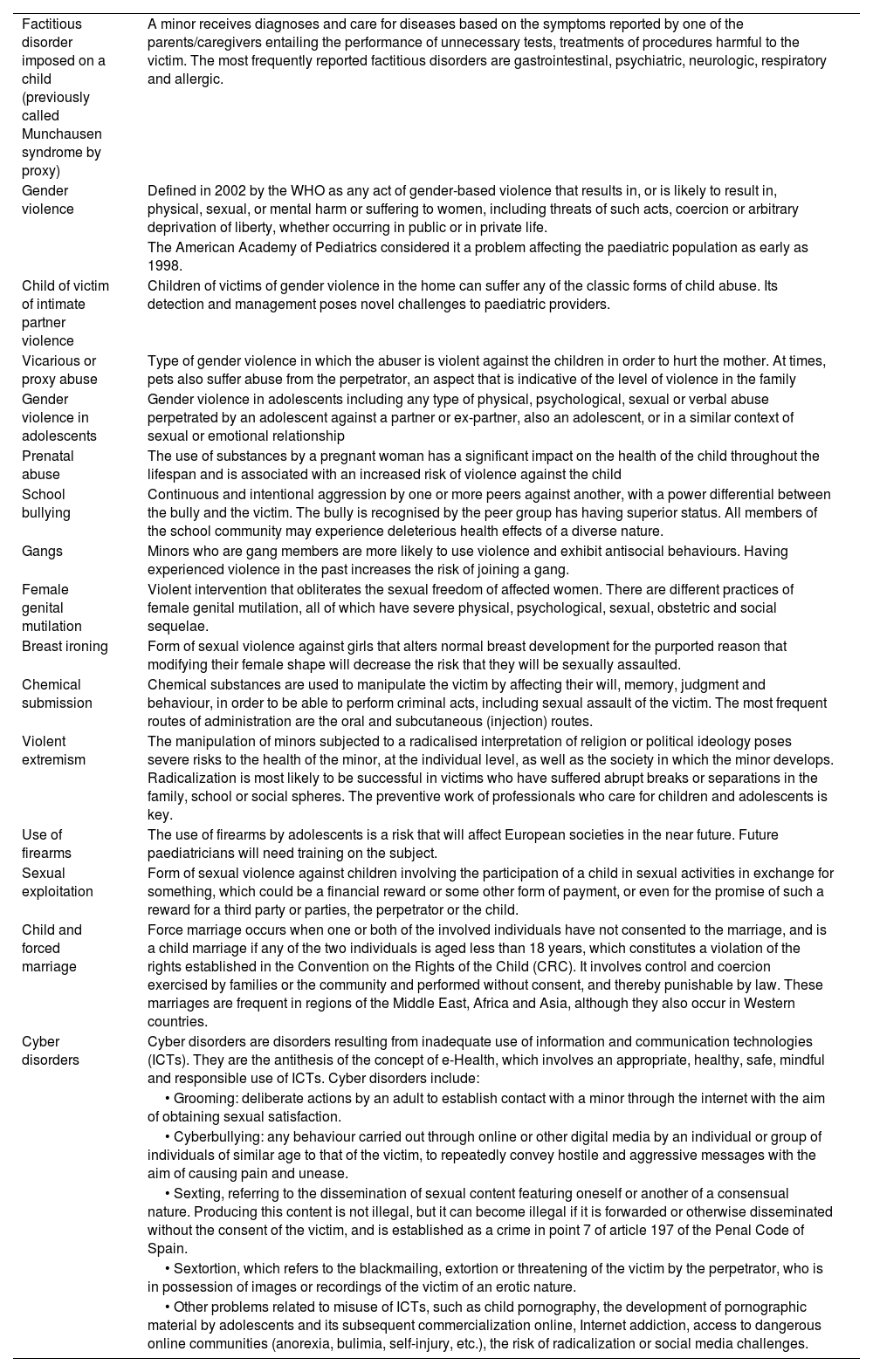

Violence against children is not limited to the 4 classical types we have discussed above. Based on the context where it takes place, the involved parties, the use of technology or other factors, different types of violence have been emerging that need to be known and that are increasingly frequently leading to seeking paediatric care services10–18 (Table 5).

Emerging forms of violence against children.

| Factitious disorder imposed on a child (previously called Munchausen syndrome by proxy) | A minor receives diagnoses and care for diseases based on the symptoms reported by one of the parents/caregivers entailing the performance of unnecessary tests, treatments of procedures harmful to the victim. The most frequently reported factitious disorders are gastrointestinal, psychiatric, neurologic, respiratory and allergic. |

| Gender violence | Defined in 2002 by the WHO as any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life. |

| The American Academy of Pediatrics considered it a problem affecting the paediatric population as early as 1998. | |

| Child of victim of intimate partner violence | Children of victims of gender violence in the home can suffer any of the classic forms of child abuse. Its detection and management poses novel challenges to paediatric providers. |

| Vicarious or proxy abuse | Type of gender violence in which the abuser is violent against the children in order to hurt the mother. At times, pets also suffer abuse from the perpetrator, an aspect that is indicative of the level of violence in the family |

| Gender violence in adolescents | Gender violence in adolescents including any type of physical, psychological, sexual or verbal abuse perpetrated by an adolescent against a partner or ex-partner, also an adolescent, or in a similar context of sexual or emotional relationship |

| Prenatal abuse | The use of substances by a pregnant woman has a significant impact on the health of the child throughout the lifespan and is associated with an increased risk of violence against the child |

| School bullying | Continuous and intentional aggression by one or more peers against another, with a power differential between the bully and the victim. The bully is recognised by the peer group has having superior status. All members of the school community may experience deleterious health effects of a diverse nature. |

| Gangs | Minors who are gang members are more likely to use violence and exhibit antisocial behaviours. Having experienced violence in the past increases the risk of joining a gang. |

| Female genital mutilation | Violent intervention that obliterates the sexual freedom of affected women. There are different practices of female genital mutilation, all of which have severe physical, psychological, sexual, obstetric and social sequelae. |

| Breast ironing | Form of sexual violence against girls that alters normal breast development for the purported reason that modifying their female shape will decrease the risk that they will be sexually assaulted. |

| Chemical submission | Chemical substances are used to manipulate the victim by affecting their will, memory, judgment and behaviour, in order to be able to perform criminal acts, including sexual assault of the victim. The most frequent routes of administration are the oral and subcutaneous (injection) routes. |

| Violent extremism | The manipulation of minors subjected to a radicalised interpretation of religion or political ideology poses severe risks to the health of the minor, at the individual level, as well as the society in which the minor develops. Radicalization is most likely to be successful in victims who have suffered abrupt breaks or separations in the family, school or social spheres. The preventive work of professionals who care for children and adolescents is key. |

| Use of firearms | The use of firearms by adolescents is a risk that will affect European societies in the near future. Future paediatricians will need training on the subject. |

| Sexual exploitation | Form of sexual violence against children involving the participation of a child in sexual activities in exchange for something, which could be a financial reward or some other form of payment, or even for the promise of such a reward for a third party or parties, the perpetrator or the child. |

| Child and forced marriage | Force marriage occurs when one or both of the involved individuals have not consented to the marriage, and is a child marriage if any of the two individuals is aged less than 18 years, which constitutes a violation of the rights established in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). It involves control and coercion exercised by families or the community and performed without consent, and thereby punishable by law. These marriages are frequent in regions of the Middle East, Africa and Asia, although they also occur in Western countries. |

| Cyber disorders | Cyber disorders are disorders resulting from inadequate use of information and communication technologies (ICTs). They are the antithesis of the concept of e-Health, which involves an appropriate, healthy, safe, mindful and responsible use of ICTs. Cyber disorders include: |

| • Grooming: deliberate actions by an adult to establish contact with a minor through the internet with the aim of obtaining sexual satisfaction. | |

| • Cyberbullying: any behaviour carried out through online or other digital media by an individual or group of individuals of similar age to that of the victim, to repeatedly convey hostile and aggressive messages with the aim of causing pain and unease. | |

| • Sexting, referring to the dissemination of sexual content featuring oneself or another of a consensual nature. Producing this content is not illegal, but it can become illegal if it is forwarded or otherwise disseminated without the consent of the victim, and is established as a crime in point 7 of article 197 of the Penal Code of Spain. | |

| • Sextortion, which refers to the blackmailing, extortion or threatening of the victim by the perpetrator, who is in possession of images or recordings of the victim of an erotic nature. | |

| • Other problems related to misuse of ICTs, such as child pornography, the development of pornographic material by adolescents and its subsequent commercialization online, Internet addiction, access to dangerous online communities (anorexia, bulimia, self-injury, etc.), the risk of radicalization or social media challenges. |

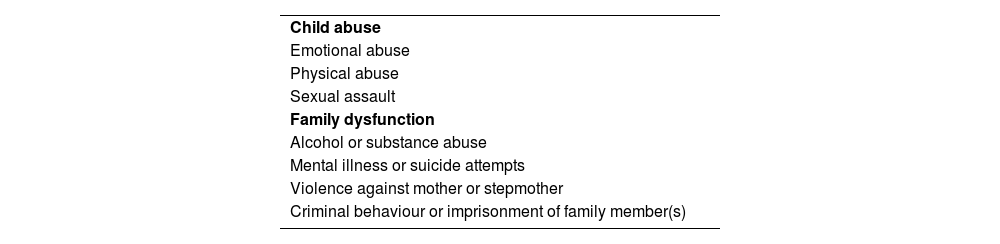

Although the immediate effects are more evident, the exposure to violence at an early age has a prolonged impact on health. Since the late 20th century, it is known that the experience during childhood of dysfunction in the family or adverse social conditions, including child abuse, is associated with the development of various diseases and risk behaviours.19 This led to the coining of the term adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which initially included 10 categories about child and family experiences. Table 6 presents the original ACE categories proposed by Vincent Felitti. The presence of 4 or more ACEs is associated with deleterious effects on health throughout the lifespan of the individual. According to a recent meta-analysis of 37 studies including 250 000 participants in total,20 the risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cancer is doubled in adults with a history of ACEs compared to the general population. The risk of substance use, mental illness or risk behaviours is four times greater, and the risk of violent behaviour in general (including attempted suicide, with an odds ratio of 30) is seven times greater. This association between ACEs and diseases that do not appear to be related to social determinants of health, combined with previous studies describing an increased incidence in common diseases of childhood21 (otitis media, viral infections, asthma, dermatitis, urticaria, gastrointestinal and urinary tract infections), have led to the recognition of early exposure to violence, with the resulting health sequelae, as one of the modifiable risk factors with the highest impact on public health.

Adverse childhood experiences.18

| Child abuse |

| Emotional abuse |

| Physical abuse |

| Sexual assault |

| Family dysfunction |

| Alcohol or substance abuse |

| Mental illness or suicide attempts |

| Violence against mother or stepmother |

| Criminal behaviour or imprisonment of family member(s) |

The scientific literature also demonstrates that the effect of violence against children is perpetuated intergenerationally, increasing the risk of exposure to violence, mental illness, substance abuse and risk behaviours in future generations.22 The pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie the long-term consequences of ACEs remain unclear. The prenatal period and the first years of life are key for the development of the central nervous system, a process in which interaction with the environment and external stimuli play an essential role. Different pathways have been proposed to explain the association between early adverse experiences and neurocognitive and psychosocial development, among which we should highlight alterations in the stress response, remodelling of synapses in the hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal and medial orbitofrontal cortex and immunologic and epigenetic changes in neurotransmitters with accelerated ageing.23 However, it is impossible to isolate the effects of ACEs and other social determinants of health. Factors like poverty, poor nutrition, housing insecurity, residing in marginalised areas or exposure to environmental pollutants probably have an impact on cognitive functions as well, especially executive functioning, which could result in poorer academic performance and an increased risk of mental illness, in addition to the subsequent development of chronic diseases and fewer opportunities in personal development, education and employment and lower incomes.24 Therefore, violence is a priority in global health.

Management of violence against childrenThe management of situations of violence against children should include a detailed history-taking and physical examination, assessing for indicators of biopsychosocial risk,25,26 observing the interactions between minors and caregivers and their behaviour and safeguarding the rights of children and adolescents. Once this initial assessment is complete, it may be useful to apply the STAR mnemonic,27 which can guide the comprehensive management of child abuse: Stop—Do you think it could be a case of child abuse?; Think—assess the certainties and uncertainties in the case; Act—contact available resources for child welfare and support; Review—Did you follow specific recommendations, protocols or algorithms for the response to suspected child abuse? This strategy fails if institutions and professionals are not genuinely invested and fully coordinated in the management of violence against children and adolescents, and to facilitate this coordination it is important to understand the difference between risk situations and situations from which the child needs to be removed.28

The severity of child abuse is determined by different factors, chiefly the age of the victim, the type and frequency of the violence experienced by the child, the emotional closeness of the perpetrator, the support available within the family, available social welfare and health care resources, socioeconomic level, etc.

In cases of mild or moderate severity in which there are physical or psychological signs or social risk factors but that allow non-urgent management, the initial intervention will be performed in the setting in which the abuse is detected and the situation will be reported to child protection services through the Risk and Abuse Report form. Child protection services will develop a family intervention plan including measures to improve the current situation, including the rest of the family in the assessment with particular emphasis on the siblings of possible victims.29 Referral to social paediatrics services or care teams specialised in the management of violence victims can be considered.

When severe child abuse is suspected, the situation is urgent, as the life and integrity of the child or adolescent are threatened. The case should be reported to law enforcement, the duty court and juvenile justice system (also when the presumed perpetrator is a minor as well) and the child protection system. The need to involve child protection services and coordination with units specialised in violence or social paediatrics should be considered. The need for hospital admission should also always be assessed.

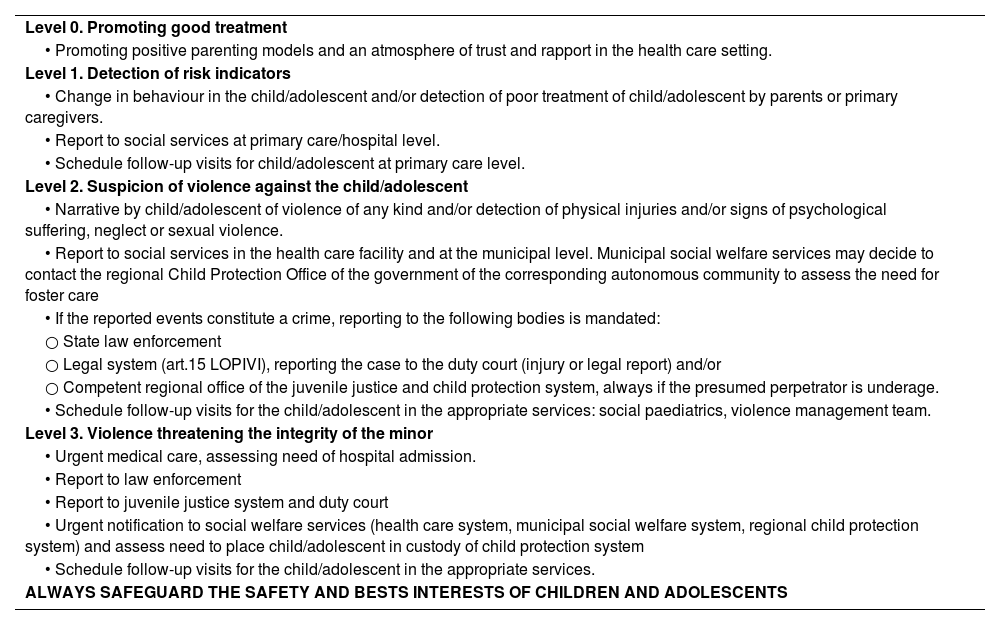

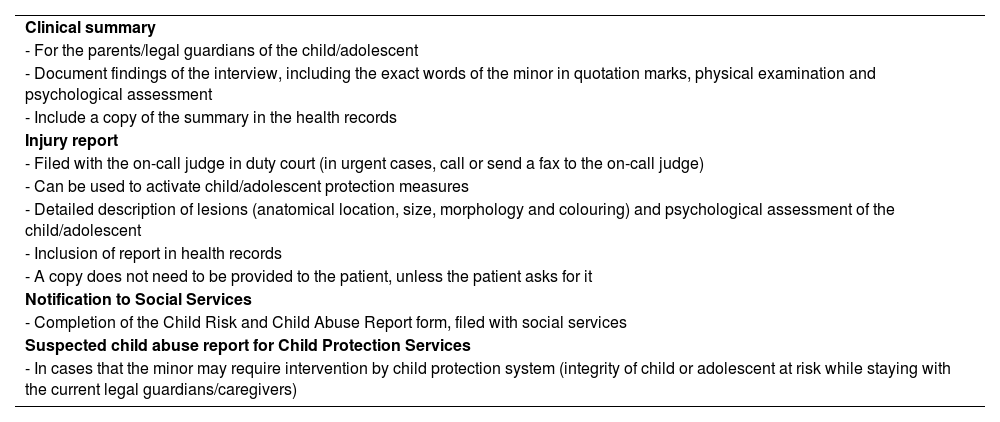

Table 7 lists the levels of intervention and Table 8 the documentation that needs to be completed.

Levels of intervention.

| Level 0. Promoting good treatment |

| • Promoting positive parenting models and an atmosphere of trust and rapport in the health care setting. |

| Level 1. Detection of risk indicators |

| • Change in behaviour in the child/adolescent and/or detection of poor treatment of child/adolescent by parents or primary caregivers. |

| • Report to social services at primary care/hospital level. |

| • Schedule follow-up visits for child/adolescent at primary care level. |

| Level 2. Suspicion of violence against the child/adolescent |

| • Narrative by child/adolescent of violence of any kind and/or detection of physical injuries and/or signs of psychological suffering, neglect or sexual violence. |

| • Report to social services in the health care facility and at the municipal level. Municipal social welfare services may decide to contact the regional Child Protection Office of the government of the corresponding autonomous community to assess the need for foster care |

| • If the reported events constitute a crime, reporting to the following bodies is mandated: |

| ○ State law enforcement |

| ○ Legal system (art.15 LOPIVI), reporting the case to the duty court (injury or legal report) and/or |

| ○ Competent regional office of the juvenile justice and child protection system, always if the presumed perpetrator is underage. |

| • Schedule follow-up visits for the child/adolescent in the appropriate services: social paediatrics, violence management team. |

| Level 3. Violence threatening the integrity of the minor |

| • Urgent medical care, assessing need of hospital admission. |

| • Report to law enforcement |

| • Report to juvenile justice system and duty court |

| • Urgent notification to social welfare services (health care system, municipal social welfare system, regional child protection system) and assess need to place child/adolescent in custody of child protection system |

| • Schedule follow-up visits for the child/adolescent in the appropriate services. |

| ALWAYS SAFEGUARD THE SAFETY AND BESTS INTERESTS OF CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS |

Forms that need to be filled out in the event of a suspected or confirmed case of violence against children.

| Clinical summary |

| - For the parents/legal guardians of the child/adolescent |

| - Document findings of the interview, including the exact words of the minor in quotation marks, physical examination and psychological assessment |

| - Include a copy of the summary in the health records |

| Injury report |

| - Filed with the on-call judge in duty court (in urgent cases, call or send a fax to the on-call judge) |

| - Can be used to activate child/adolescent protection measures |

| - Detailed description of lesions (anatomical location, size, morphology and colouring) and psychological assessment of the child/adolescent |

| - Inclusion of report in health records |

| - A copy does not need to be provided to the patient, unless the patient asks for it |

| Notification to Social Services |

| - Completion of the Child Risk and Child Abuse Report form, filed with social services |

| Suspected child abuse report for Child Protection Services |

| - In cases that the minor may require intervention by child protection system (integrity of child or adolescent at risk while staying with the current legal guardians/caregivers) |

When children or adolescents report being a victim of violence, they often need to report their experiences several times, which contributes to secondary victimization. The Barnahus model,30 which is gradually being introduced throughout Spain and was initially developed for cases of SVC but subsequently expanded to other types of child abuse, is an approach that safeguards the rights, health and integrity of minors. To implement it, there will be a progressive integration of all the agencies and institutions with the aim of pursuing the best interests of the minor. The cornerstone of the model is that the child or adolescent should only be subjected to a single forensic interview that would later be admissible as pre-appointed evidence in court31 and remain valid for the duration of the legal process.

Prevention, good treatment, protective factors and resilienceThe LOPIVI defines good treatment of minors as respecting the fundamental rights of children and adolescents and promotes the principles of mutual respect, the dignity of human beings, democratic coexistence, peaceful conflict resolution, equal rights and protection under the law, equal opportunity and non-discrimination of children and adolescents. Another concept along the lines of good treatment is positive parenting,32 which refers to parents acting based on the best interests of the child, nurturing their development and abilities, never using violence and offering guidance, including the establishment of boundaries, to allow the full development of the child.

The prevention of violence is a key issue, given its impact on health, but it requires a multidisciplinary and comprehensive approach. For instance, the INSPIRE programme,33 developed by the WHO, proposes and elaborates on seven evidence-based strategies to reduce violence against children. Chief of them are the strategies based on norms and values, parent and caregiver support and response and support services. Its implementation requires comprehensive partnerships with coordination of health care systems, community resources, education systems, social and welfare services, the legal system and law enforcement.

Another fundamental aspect is the promotion of protective factors, both in victims and in the professionals caring for them.34 We know that there is substantial variation in individual responses to violent situations, and that this variation is related to what we know as resilience, understood as positive coping of the individual subjected to challenging and traumatic life events, overcoming adversity and transforming painful experiences into opportunities for growth and development.35 By promoting good treatment, resilience, the detection of ACEs and positive childhood experiences (PCEs), whose importance has been recently demonstrated,36 health care professionals can play a key role in the suppression of the effects of violence on the victims.37

In the present article, we have offered a succinct and up-to-date perspective on the terrible impact of violence on children. This approach supports the undertaking of a comprehensive approach to paediatric care now and in the future. The future needs a holistic perspective,38 based on the interaction between the child and the child’s family, social, cultural and environmental context. General Comment No. 26 of the Committee on the Rights of the Child considers environmental degradation, including climate change, a form of structural violence against children and adolescents.39 Knowledge of the social determinants of health and of adverse as well as positive childhood experiences will facilitate the provision of comprehensive care and the prevention of adverse experiences in early life, and therefore help children and adolescents reach their full human potential while building a more just and democratic society.

ConclusionWe conclude by quoting the words of psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman about trauma, the manifestation of the damage caused by violence.40 It is a call for the professional and ethical commitment of every professional involved in the care and support of children. “To study psychological trauma means bearing witness to horrible events […] But when the traumatic events are of human design, those who bear witness are caught in the conflict between victim and perpetrator. It is morally impossible to remain neutral in this conflict. It is very tempting to take the side of the perpetrator. All the perpetrator asks is that the bystander do nothing. He appeals to the universal desire to see, hear, and speak no evil […] After every atrocity one can expect to hear [that] it never happened; the victim lies; the victim exaggerates; the victim brought it on herself; and in any case it is time to forget the past and move on […] The victim, on the contrary, asks the bystander to share the burden of pain. The victim demands action, engagement, and remembering.”

BBQL has received a Río Hortega Grant from the Carlos III Health Institute - Ministry of Health, co-financed by Feder Funds from the European Union (CM23/00057). TS has received a grant from the European Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID Springboard Award).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.