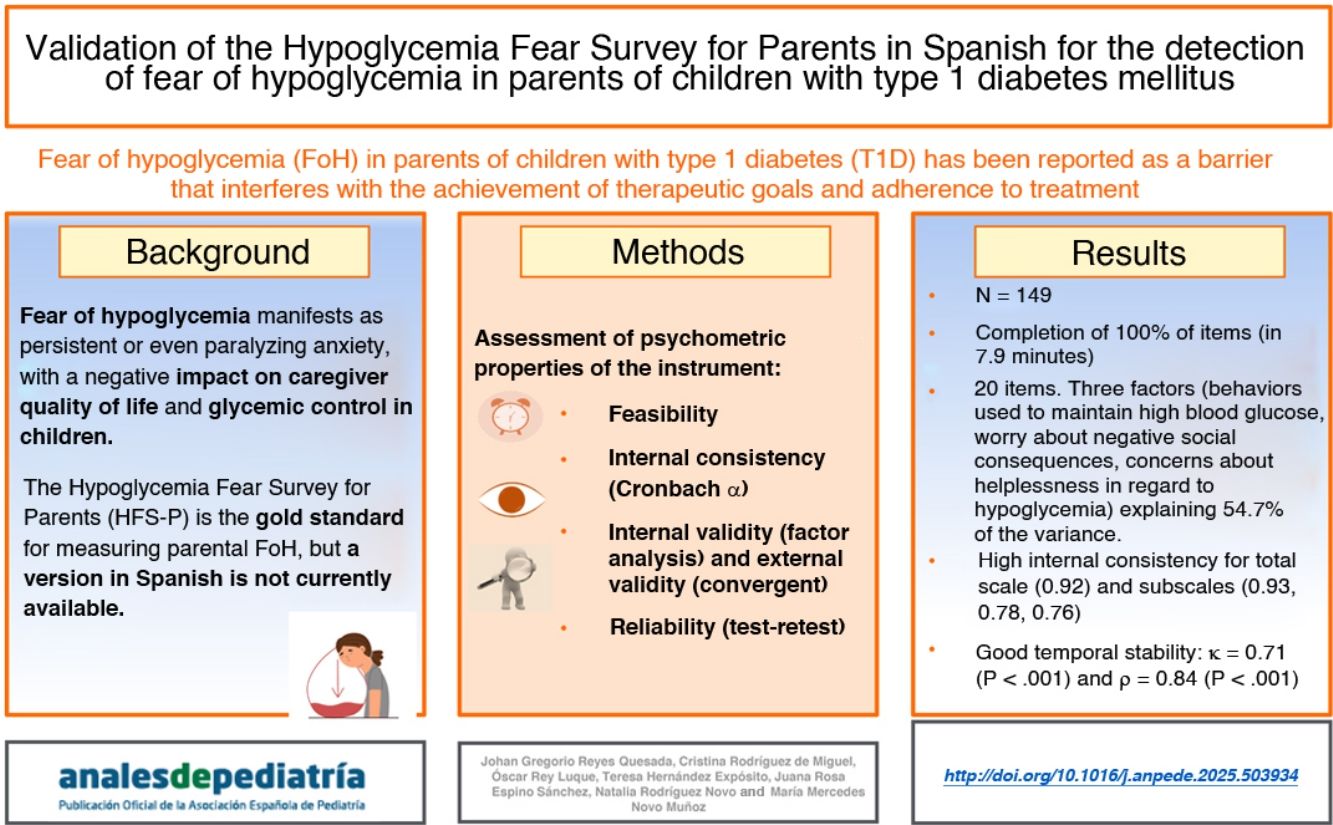

Fear of hypoglycemia (FoH) in parents of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) has been described as a barrier that affects the achievement of therapeutic goals and adherence to treatment. Objective: validating the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Parents (HFS-P) in Spanish and assessing the relationship between scores and various clinical variables.

MethodsWe conducted a psychometric analysis of the instrument, evaluating its feasibility, internal consistency, validity and reliability in the intended setting and population.

ResultsThe sample included a total of 149 participants (71.8% mothers). The mean age of the children was 9.9 years (SD, 3.2), with a mean duration of T1DM duration of 3.9 years (SD, 3.5) and a mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7.9% (SD, 1.9). Of all participants, 87.9% reported the use of new technologies for glucose monitoring. The adapted questionnaire consists of 20 items grouped into three dimensions. The Cronbach α for the total scale was 0.92. The HFS-P was significantly correlated to a general worry scale (ρ = 0.47; P < .001). The test-retest reliability analysis showed a strong positive correlation (ρ = 0.84; P < .001). Variables such as family history of T1DM, caregiver educational level, HbA1c level and use of a glucose monitoring system were significantly associated with HFS-P scores.

ConclusionThe Spanish version of the HFS-P is a valid and reliable tool that may assist health care professionals in identifying parental FoH and guide the development of interventions aimed at improving disease management in children.

El miedo a la hipoglucemia (MaH) en los padres de niños con Diabetes Mellitus tipo 1 (DM1) se ha descrito como una barrera que influye en el logro de los objetivos terapéuticos y en la adherencia al tratamiento. Objetivo: Validar al español el cuestionario Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Parents (HFS-P) y establecer relación entre las puntuaciones y distintas variables clínicas.

Material y metodoSe realizó un análisis de las propiedades psicométricas del instrumento (factibilidad, consistencia interna, validez y fiabilidad) en el contexto de destino.

ResultadosParticiparon 149 sujetos (71.8% madres). La edad de los niños fue de 9.9 ± 3.2 años, con un tiempo de diagnóstico de la DM1 de 3.9 ± 3.5 años y una hemoglobina glicosilada (HbA1c) media de 7.9% ± 1,9. El 87.9% utilizaba nuevas tecnologías para el control de la glucosa. El nuevo cuestionario consta de 20 ítems y 3 dimensiones. El alfa de Cronbach para el cuestionario total fue de 0.92. Se correlacionó el cuestionario con otro sobre la preocupación general (ρ = 0.47; p < 0.001). Para la fiabilidad test-retest, se obtuvo una correlación positiva ρ = 0.84 (p < 0.001). Antecedentes familiares de DM1, nivel académico del cuidador, nivel de HbA1c o sistema de control de glucosa, se asociaron significativamente con las puntuaciones del cuestionario.

ConclusionLa versión española del HFS-P se ha mostrado como una herramienta válida y fiable que podría ayudar a los profesionales sanitarios a detectar el MaH de los padres y orientarles en el desarrollo de intervenciones que mejoren el control de la enfermedad del menor.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) presents unique challenges in the pediatric population, in relation to the need to control blood glucose levels at all times. One of the critical elements in this scenario is the fear of hypoglycemia (FoH) experienced by parents of children with T1D. This psychosocial phenomenon manifests as persistent and even paralyzing anxiety, affecting parental quality of life and disease control.1 Previous studies have found that constant fear of hypoglycemia can lead to suboptimal management practices (such as omitting an insulin dose or unduly restricting carbohydrate intake), behaviors that, while meant to prevent hypoglycemic episodes, end up compromising optimal glucose control and long-term health in children with T1D.2,3 In addition, sustained FoH contributes to high levels of stress and fatigue in parents, affecting family dynamics and their ability to adequately manage diabetes in their children.4 In this context, it is essential to implement interventions aimed at detecting and mitigating FoH in caregivers, including ongoing diabetes education, emotional support and development of effective coping strategies. At present, the instrument of choice to quantify parental FoH is the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Parents (HFS-P).5 This questionnaire has been translated and validated to several languages,6–12 but there is no validated version in Spanish, so it is not possible to determine the degree of FoH in Spain or compare it to other countries. In 2020, the HFS-P underwent cultural adaptation and translation to Spanish,13 but the psychometric properties of the resulting instrument were not evaluated. Thus, we felt the need to validate the HFS-P in the Spanish population to make available a reliable tool for assessing FoH in the management of children with T1D in Spain, as well as analyzing the association between the level of FoH in parents and several clinical variables to identify factors related to this fear.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study for questionnaire validation, assessing the psychometric properties of the instrument (feasibility, construct validity, criterion validity, internal consistency and reliability) in the target population and analyzing the potential association of the instrument with relevant clinical variables.

Psychometric validationWe included parents or primary caregivers of children with T1D (age ≤ 14 years) managed in the pediatric endocrinology outpatient clinic of the two hospitals in Tenerife over a 3-month period. We excluded those who were not fluent in Spanish as well as caregivers of children with forms of diabetes other than T1D or with comorbidities. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines (sponsor’s protocol code CHUNSC_2019_16), and we obtained signed informed consent from the participants and safeguarded the confidentiality of the data. The sample size was calculated based on the recommendations of several authors for calculating the size required to test construct validity.14,15 These authors recommend calculation based on item-to-response ratios ranging from three to 20 subjects per item, although a minimum ratio of five subjects per item is generally recommended. Last of all, we decided to pursue a sample size of 135, and, expecting losses of approximately 10%, settled on an initial sample size of 149. Participants were recruited consecutively until the desired sample size was reached.

We calculated descriptive statistics for sociodemographic and clinical variables. Feasibility was assessed by means of the completion time and the percentage of items completed by participants. Construct validity was assessed by means of factor analysis (FA). To determine whether the data were suitable for FA, we used the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), applying the recommended threshold (> 0.5) and the Bartlett test of sphericity (P < .05).16 In FA, we tried different extraction and rotation methods. We eliminated items with correlations of less than 0.4 and those that did not correlate to any factor. The extraction method that yielded the best results was principal axis factoring with direct oblimin rotation (oblique rotation). Internal consistency was assessed through the calculation of Cronbach α coefficients for the total and subscale scores, considering values greater than 0.70 indicative of acceptable consistency. For convergent validity, we analysed the correlation between the total and subscale scores of the HFS-P with the validated Spanish version of the 11-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ-1117 (used to assess the tendency of the individual to experience general anxiety) using the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ). Last of all, to assess test-retest reliability, we asked participants to complete the questionnaire again two weeks after the first administration. We then calculated the Cohen kappa coefficient (κ) of agreement after categorizing scores into tertiles (low FoH, moderate FoH, high FoH). We also calculated the Spearman coefficient to assess the correlation between the total and subscale scores obtained in each timepoint.

For the analysis of the association with clinical variables, we started by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to determine whether the data followed a normal distribution. We then used the Mann–Whitney U test (Wilcoxon rank-sum test for two independent samples) to compare the variables. We considered P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. The data were analyzed with the statistical package SPSS version 25.0.

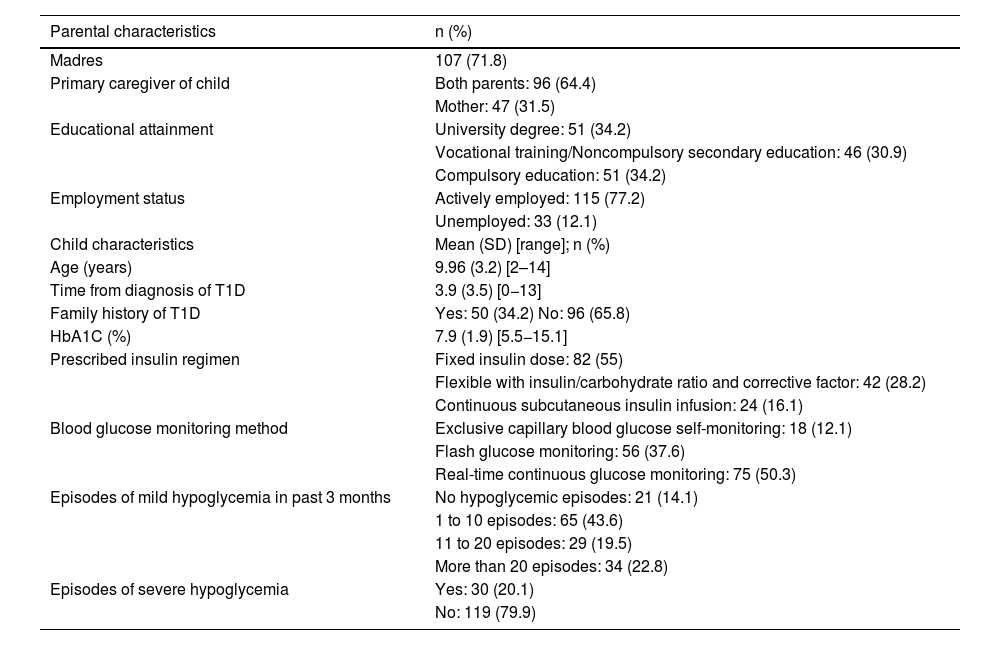

ResultsWe recruited 152 caregivers, eventually excluding three (two due to refusal to participate and one due to a language barrier). The final sample included 149 participants. Table 1 summarize the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Parental characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Madres | 107 (71.8) |

| Primary caregiver of child | Both parents: 96 (64.4) |

| Mother: 47 (31.5) | |

| Educational attainment | University degree: 51 (34.2) |

| Vocational training/Noncompulsory secondary education: 46 (30.9) | |

| Compulsory education: 51 (34.2) | |

| Employment status | Actively employed: 115 (77.2) |

| Unemployed: 33 (12.1) | |

| Child characteristics | Mean (SD) [range]; n (%) |

| Age (years) | 9.96 (3.2) [2–14] |

| Time from diagnosis of T1D | 3.9 (3.5) [0−13] |

| Family history of T1D | Yes: 50 (34.2) No: 96 (65.8) |

| HbA1C (%) | 7.9 (1.9) [5.5−15.1] |

| Prescribed insulin regimen | Fixed insulin dose: 82 (55) |

| Flexible with insulin/carbohydrate ratio and corrective factor: 42 (28.2) | |

| Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: 24 (16.1) | |

| Blood glucose monitoring method | Exclusive capillary blood glucose self-monitoring: 18 (12.1) |

| Flash glucose monitoring: 56 (37.6) | |

| Real-time continuous glucose monitoring: 75 (50.3) | |

| Episodes of mild hypoglycemia in past 3 months | No hypoglycemic episodes: 21 (14.1) |

| 1 to 10 episodes: 65 (43.6) | |

| 11 to 20 episodes: 29 (19.5) | |

| More than 20 episodes: 34 (22.8) | |

| Episodes of severe hypoglycemia | Yes: 30 (20.1) |

| No: 119 (79.9) |

Abbreviations: HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin; T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Participants completed 100% of the items, and the mean completion time was approximately 7.9 min (SD, 2.2), demonstrating the feasibility of the questionnaire for use in clinical practice.

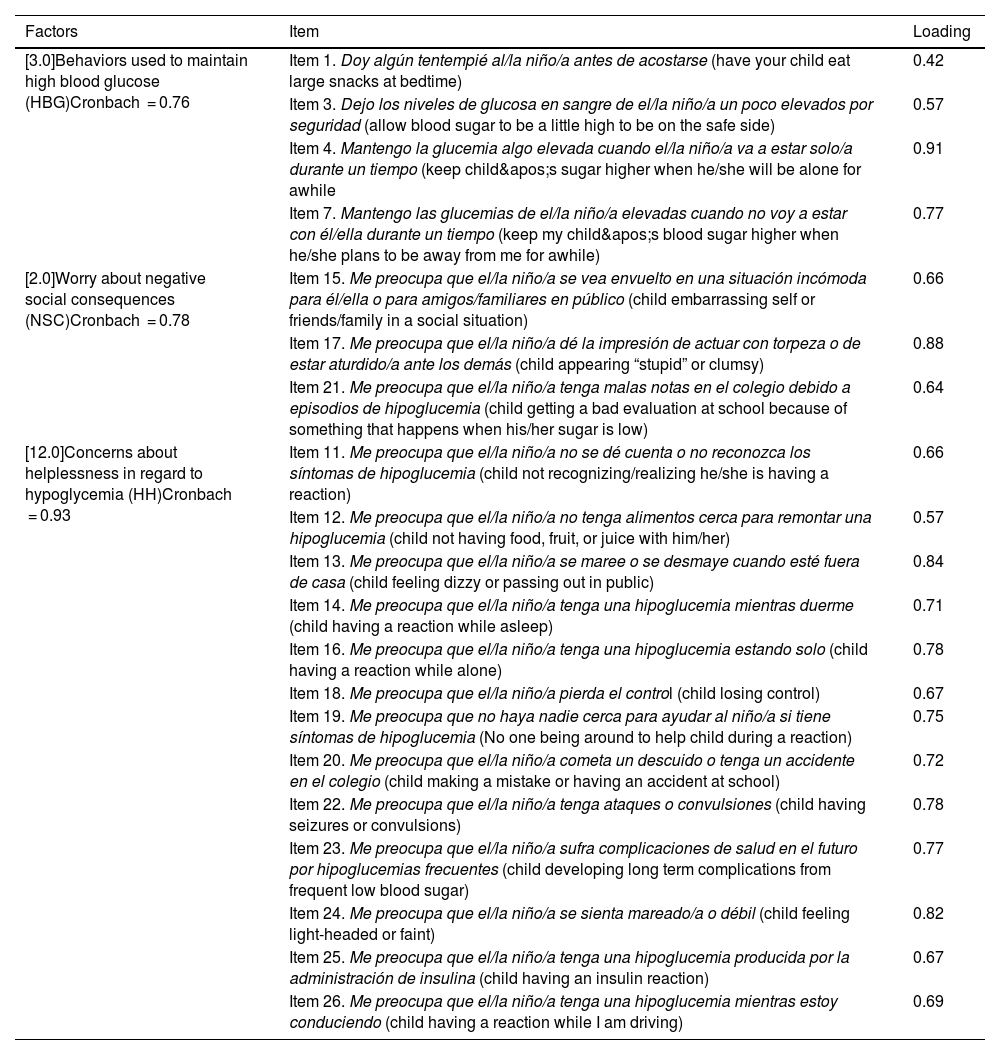

Construct validity (factor analysis)First, we studied the factor structure of the entire instrument by means of exploratory factor analysis. Examining the structure matrix, we identified several items with factor loadings below the acceptable threshold, as well as items with loadings inconsistent with the hypothesized structure established in previous validation studies conducted in other countries. Items 5, 6 and 8 did not reach factor loadings of 0.40 or greater on any of the emerging constructs. Items 2, 9 and 10, while exhibiting acceptable loadings, have been considered conceptually weak or unstable in previous studies, as they refer to avoidance behaviors with low communality with the central dimensions of the FoH construct. In addition, inclusion of these items generated a more disperse factor structure with poorly defined or single-item factors, which compromises the parsimony and conceptual coherence of the model. After refining the instrument, we repeated the factor analysis with the remaining items. We obtained a KMO of 0.90 (Bartlett’s sphericity test: P < .001). The resulting model yielded a solution with three well-defined factors that were consistent both with the expected theoretical structure and the observed psychometric properties (Table 2). All items had loadings between 0.42 and 0.91, explaining 54.7% of the total variance. The new solution improved the structural clarity and reinforced the internal validity of the instrument in the study sample. Factor 1 corresponded to “behaviors used to maintain high blood glucose” (HBG), composed by four items, factor 2 to “worry about negative social consequences” (NSC), composed by three items, and factor 3 to “concerns about helplessness in regard to hypoglycemia” (HH), composed by 13 items. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the final version of the questionnaire.

Factors extracted from the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Parents (HFS-P) in Spanish and item factor loadings.

| Factors | Item | Loading |

|---|---|---|

| [3.0]Behaviors used to maintain high blood glucose (HBG)Cronbach = 0.76 | Item 1. Doy algún tentempié al/la niño/a antes de acostarse (have your child eat large snacks at bedtime) | 0.42 |

| Item 3. Dejo los niveles de glucosa en sangre de el/la niño/a un poco elevados por seguridad (allow blood sugar to be a little high to be on the safe side) | 0.57 | |

| Item 4. Mantengo la glucemia algo elevada cuando el/la niño/a va a estar solo/a durante un tiempo (keep child's sugar higher when he/she will be alone for awhile | 0.91 | |

| Item 7. Mantengo las glucemias de el/la niño/a elevadas cuando no voy a estar con él/ella durante un tiempo (keep my child's blood sugar higher when he/she plans to be away from me for awhile) | 0.77 | |

| [2.0]Worry about negative social consequences (NSC)Cronbach = 0.78 | Item 15. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a se vea envuelto en una situación incómoda para él/ella o para amigos/familiares en público (child embarrassing self or friends/family in a social situation) | 0.66 |

| Item 17. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a dé la impresión de actuar con torpeza o de estar aturdido/a ante los demás (child appearing “stupid” or clumsy) | 0.88 | |

| Item 21. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga malas notas en el colegio debido a episodios de hipoglucemia (child getting a bad evaluation at school because of something that happens when his/her sugar is low) | 0.64 | |

| [12.0]Concerns about helplessness in regard to hypoglycemia (HH)Cronbach = 0.93 | Item 11. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a no se dé cuenta o no reconozca los síntomas de hipoglucemia (child not recognizing/realizing he/she is having a reaction) | 0.66 |

| Item 12. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a no tenga alimentos cerca para remontar una hipoglucemia (child not having food, fruit, or juice with him/her) | 0.57 | |

| Item 13. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a se maree o se desmaye cuando esté fuera de casa (child feeling dizzy or passing out in public) | 0.84 | |

| Item 14. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia mientras duerme (child having a reaction while asleep) | 0.71 | |

| Item 16. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia estando solo (child having a reaction while alone) | 0.78 | |

| Item 18. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a pierda el control (child losing control) | 0.67 | |

| Item 19. Me preocupa que no haya nadie cerca para ayudar al niño/a si tiene síntomas de hipoglucemia (No one being around to help child during a reaction) | 0.75 | |

| Item 20. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a cometa un descuido o tenga un accidente en el colegio (child making a mistake or having an accident at school) | 0.72 | |

| Item 22. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga ataques o convulsiones (child having seizures or convulsions) | 0.78 | |

| Item 23. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a sufra complicaciones de salud en el futuro por hipoglucemias frecuentes (child developing long term complications from frequent low blood sugar) | 0.77 | |

| Item 24. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a se sienta mareado/a o débil (child feeling light-headed or faint) | 0.82 | |

| Item 25. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia producida por la administración de insulina (child having an insulin reaction) | 0.67 | |

| Item 26. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia mientras estoy conduciendo (child having a reaction while I am driving) | 0.69 |

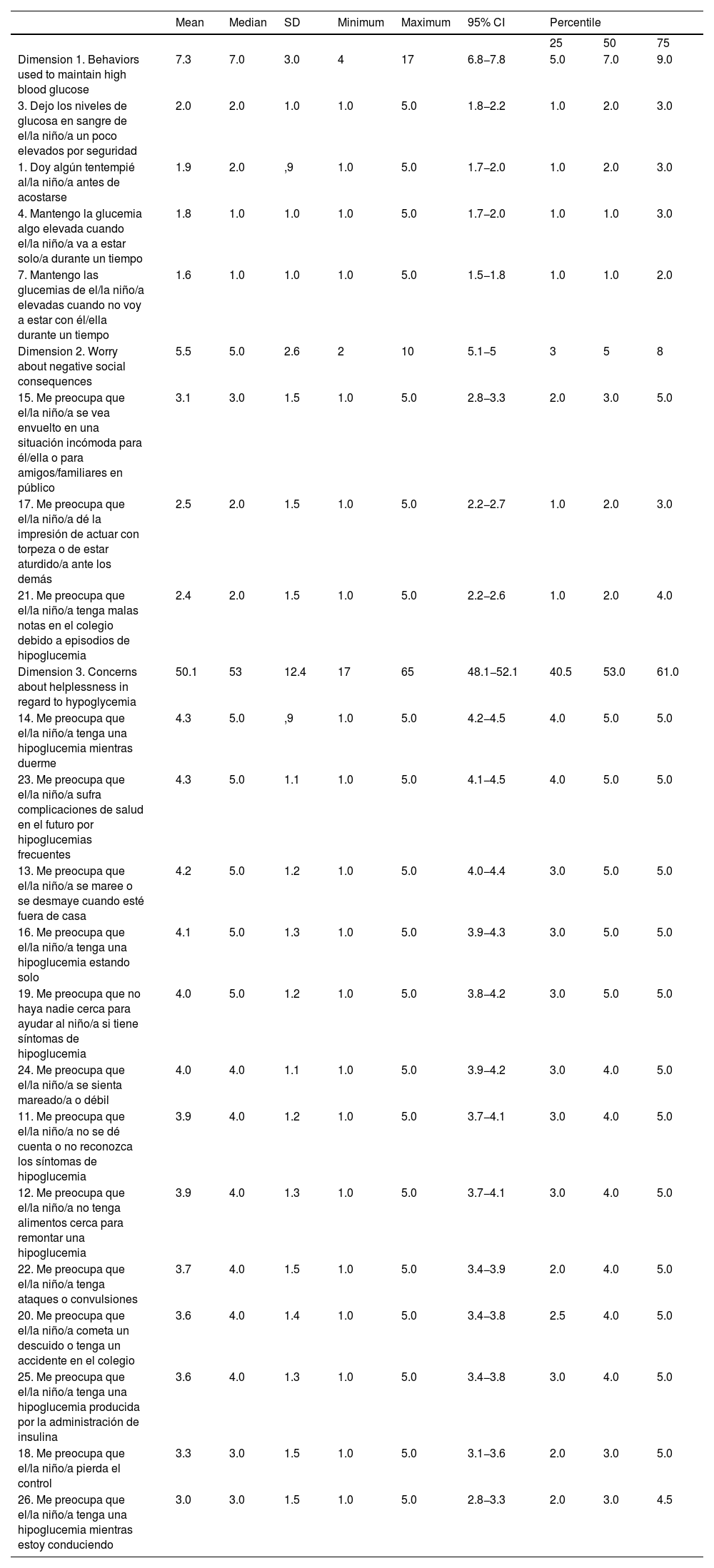

Descriptive statistics for the scores in the items of the Spanish version of the HFS-P.

| Mean | Median | SD | Minimum | Maximum | 95% CI | Percentile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 | 75 | |||||||

| Dimension 1. Behaviors used to maintain high blood glucose | 7.3 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 4 | 17 | 6.8−7.8 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 9.0 |

| 3. Dejo los niveles de glucosa en sangre de el/la niño/a un poco elevados por seguridad | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.8−2.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 1. Doy algún tentempié al/la niño/a antes de acostarse | 1.9 | 2.0 | ,9 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.7−2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 4. Mantengo la glucemia algo elevada cuando el/la niño/a va a estar solo/a durante un tiempo | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.7−2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| 7. Mantengo las glucemias de el/la niño/a elevadas cuando no voy a estar con él/ella durante un tiempo | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.5−1.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Dimension 2. Worry about negative social consequences | 5.5 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 2 | 10 | 5.1−5 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| 15. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a se vea envuelto en una situación incómoda para él/ella o para amigos/familiares en público | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.8−3.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| 17. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a dé la impresión de actuar con torpeza o de estar aturdido/a ante los demás | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.2−2.7 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 21. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga malas notas en el colegio debido a episodios de hipoglucemia | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.2−2.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| Dimension 3. Concerns about helplessness in regard to hypoglycemia | 50.1 | 53 | 12.4 | 17 | 65 | 48.1−52.1 | 40.5 | 53.0 | 61.0 |

| 14. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia mientras duerme | 4.3 | 5.0 | ,9 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.2−4.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 23. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a sufra complicaciones de salud en el futuro por hipoglucemias frecuentes | 4.3 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.1−4.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 13. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a se maree o se desmaye cuando esté fuera de casa | 4.2 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.0−4.4 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 16. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia estando solo | 4.1 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.9−4.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 19. Me preocupa que no haya nadie cerca para ayudar al niño/a si tiene síntomas de hipoglucemia | 4.0 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.8−4.2 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 24. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a se sienta mareado/a o débil | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.9−4.2 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 11. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a no se dé cuenta o no reconozca los síntomas de hipoglucemia | 3.9 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.7−4.1 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 12. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a no tenga alimentos cerca para remontar una hipoglucemia | 3.9 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.7−4.1 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 22. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga ataques o convulsiones | 3.7 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.4−3.9 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 20. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a cometa un descuido o tenga un accidente en el colegio | 3.6 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.4−3.8 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 25. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia producida por la administración de insulina | 3.6 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.4−3.8 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 18. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a pierda el control | 3.3 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.1−3.6 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| 26. Me preocupa que el/la niño/a tenga una hipoglucemia mientras estoy conduciendo | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.8−3.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

Abbreviation: HFS-P, Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Parents.

The questionnaire exhibited a good internal reliability. We obtained a Cronbach α of 0.92 for the total scale and α values of 0.76, 0.78 and 0.93 for the HBG, NSC and HH subscales, respectively, all of them indicative of good internal consistency.

Convergent validityWe found a moderate positive correlation between the HFS-P and PSWQ-11 total scores (ρ = 0.47; P < .001). The results by subscale were: HBG, ρ = 0.09 (P = .28); NSC, ρ = 0.33 (P < .001) and HH, ρ = 0.49 (P < .001). This suggests a generally increased likelihood of worrying in association with an elevated FoH.

Test-retest reliabilityThe response rate in the second round was 35%. We found substantial agreement between the scores obtained in the initial assessment and those obtained at two weeks, with a κ value of 0.71 (P < .001) and y percent agreement of 80.4%. Applying standard criteria, this indicates an acceptable measurement consistency over time. The correlation coefficients obtained in the comparison of the scores were ρ = 0.84 (P < .001) for the total scale, ρ = 0.76 (P < .001) for the HBG subscale, ρ = 0.63 (P < .001) for the NSC subscale and ρ = 0.88 (P < .001) for the HH subscale.

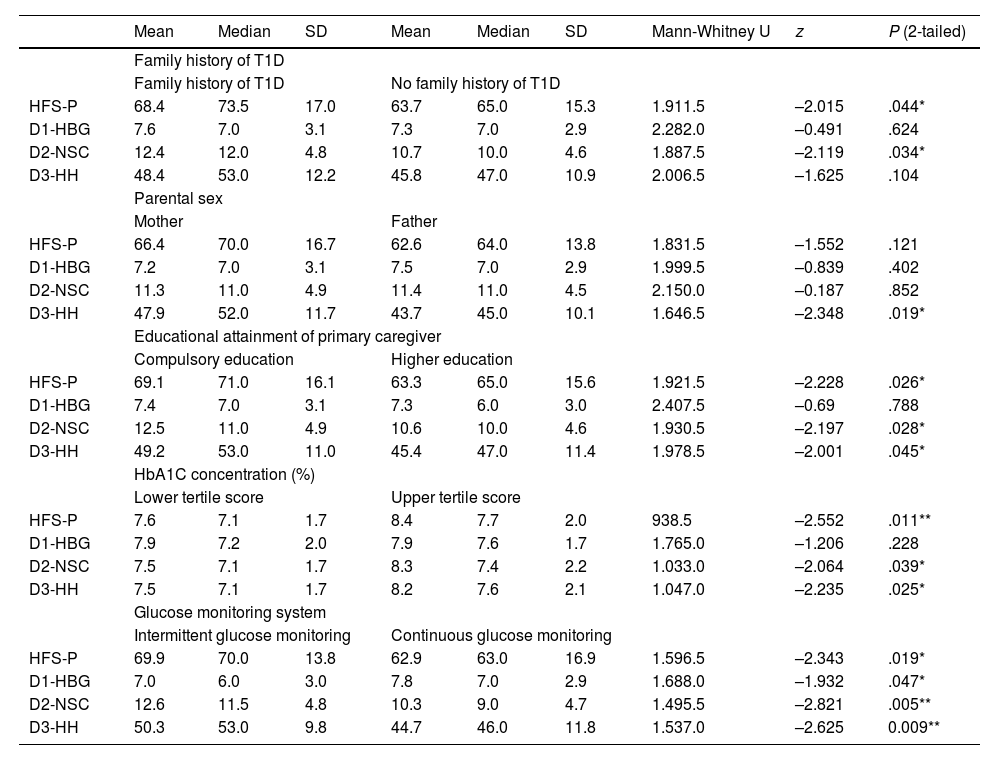

Association with clinical variablesThe FoH scores varied significantly in relation to different clinical variables, but not to parental sex (mothers, 66.4 [SD, 16.7] vs fathers 62.6 [SD, 13.8]; P = .12). Specifically, parents with a family history of T1D exhibited greater FoH compared to those without such history (68.4 [SD, 17] vs 63.7 [SD, 15.3]; P = .04). In addition, caregivers with higher educational attainment exhibited less fear compared to caregivers who had only completed compulsory education (63.3 [SD, 15.6] vs 69.1 [SD, 16.1]; P = .03). We also found that a higher mean HbA1c concentration in children of parents with elevated FoH (upper tertile) compared to children of parents with low FoH (8.4 [SD, 2.0%] vs 7.6 [SD, 1.7%]; P = .001). Last of all, parents of children managed with continuous glucose monitoring expressed less fear than parents of children with intermittent glucose monitoring (62.9 [SD, 16.9] vs 69.9 [SD, 16.0]; P = .02). Table 4 presents the findings of the correlation analysis.

Comparison of independent variables with questionnaire scores.

| Mean | Median | SD | Mean | Median | SD | Mann-Whitney U | z | P (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of T1D | |||||||||

| Family history of T1D | No family history of T1D | ||||||||

| HFS-P | 68.4 | 73.5 | 17.0 | 63.7 | 65.0 | 15.3 | 1.911.5 | –2.015 | .044* |

| D1-HBG | 7.6 | 7.0 | 3.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 2.282.0 | –0.491 | .624 |

| D2-NSC | 12.4 | 12.0 | 4.8 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 1.887.5 | –2.119 | .034* |

| D3-HH | 48.4 | 53.0 | 12.2 | 45.8 | 47.0 | 10.9 | 2.006.5 | –1.625 | .104 |

| Parental sex | |||||||||

| Mother | Father | ||||||||

| HFS-P | 66.4 | 70.0 | 16.7 | 62.6 | 64.0 | 13.8 | 1.831.5 | –1.552 | .121 |

| D1-HBG | 7.2 | 7.0 | 3.1 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 1.999.5 | –0.839 | .402 |

| D2-NSC | 11.3 | 11.0 | 4.9 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 4.5 | 2.150.0 | –0.187 | .852 |

| D3-HH | 47.9 | 52.0 | 11.7 | 43.7 | 45.0 | 10.1 | 1.646.5 | –2.348 | .019* |

| Educational attainment of primary caregiver | |||||||||

| Compulsory education | Higher education | ||||||||

| HFS-P | 69.1 | 71.0 | 16.1 | 63.3 | 65.0 | 15.6 | 1.921.5 | –2.228 | .026* |

| D1-HBG | 7.4 | 7.0 | 3.1 | 7.3 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 2.407.5 | –0.69 | .788 |

| D2-NSC | 12.5 | 11.0 | 4.9 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 1.930.5 | –2.197 | .028* |

| D3-HH | 49.2 | 53.0 | 11.0 | 45.4 | 47.0 | 11.4 | 1.978.5 | –2.001 | .045* |

| HbA1C concentration (%) | |||||||||

| Lower tertile score | Upper tertile score | ||||||||

| HFS-P | 7.6 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 938.5 | –2.552 | .011** |

| D1-HBG | 7.9 | 7.2 | 2.0 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 1.7 | 1.765.0 | –1.206 | .228 |

| D2-NSC | 7.5 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 2.2 | 1.033.0 | –2.064 | .039* |

| D3-HH | 7.5 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 1.047.0 | –2.235 | .025* |

| Glucose monitoring system | |||||||||

| Intermittent glucose monitoring | Continuous glucose monitoring | ||||||||

| HFS-P | 69.9 | 70.0 | 13.8 | 62.9 | 63.0 | 16.9 | 1.596.5 | –2.343 | .019* |

| D1-HBG | 7.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 1.688.0 | –1.932 | .047* |

| D2-NSC | 12.6 | 11.5 | 4.8 | 10.3 | 9.0 | 4.7 | 1.495.5 | –2.821 | .005** |

| D3-HH | 50.3 | 53.0 | 9.8 | 44.7 | 46.0 | 11.8 | 1.537.0 | –2.625 | 0.009** |

Abbreviations: D, dimension; HBG, behaviors used to maintain high blood glucose; HH, concerns about helplessness in regard to hypoglycemia; HFS-P, Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Parents; NSC, worry about negative social consequences.

Intergroup comparison with Mann–Whitney U test.

This study is the first validation study of a Spanish version of a questionnaire to measure fear of hypoglycemia in parents of children with T1D. Having a validated Spanish version of the HFS-P will allow, for the first time, the standardized assessment of this important psychosocial aspect in our country and to compare domestic and international results. Given that the HFS-P is the instrument used most frequently in the literature to analyze parental FoH, the availability of a Spanish version ensures that our data can be compared rigorously with data from other countries, facilitating the exchange of knowledge and the performance of international multicenter studies on the subject. In our validation study of the Spanish version of the HFS-P, we identified a structure with three subscales, in contrast to some of the previous studies in other countries that reported only two factors. For instance, validation studies conducted in Norway,7 Italy11 or Turkey10 reported two principal factors, in agreement with the original version developed by Clarke et al5 and the modified version of Patton et al18 (worry and behavior). However, more recent studies have questioned this two-dimensional structure. Specifically, Shepard et al.,19 after conducting an EFA of the HFS-P, found that the items fit better in a four-factor solution, although one of the factors (corresponding to actions to avoid hypoglycemia) had a suboptimal internal consistency (Cronbach α of approximately 0.60). Based on these findings, O’Donnell et al., in a study conducted in a large sample of parents (n > 1100),20 proposed a revision of the questionnaire, eliminating precisely the items in the avoidance dimension with a poor reliability. The revision yielded a three-factor model with an acceptable internal consistency in all three (α > 0.78). The validation study of the Greek version of the instrument, conducted by Kostopoulou et al.,12 also found an underlying three-factor structure, yielding a solution with α values greater than 0.79 for all dimensions after the elimination of 8 items from the Behavior dimension. Our results support the validity of a three-factor model similar to the one proposed by these authors. In our study, the elimination of six items yielded a final instrument with 20 items, a clear three-dimensional structure and consistent psychometric properties. All factor loadings were greater than 0.4, which indicates that each item is strongly associated with the underlying dimension. We found a high internal consistency for the total scale and all subscales, even exceeding the values reported in the Italian and Turkish validation studies and comparable to the values reported by Shepard,19 O’Donnell20 and Kostopoulou12 in their respective analyses. This suggests that the Spanish version of the HFS-P is a valid instrument for assessment of FoH in the Spanish population, and that no information has been lost with the elimination of the items. As regards the test-retest reliability, this aspect had only been evaluated in the validation of the Greek version of the HFS-P. In that case, the response rate in the second timepoint and the correlation values were lower compared to those in our study. We found an excellent temporal stability for the total scale. At the subscale level, we found substantial stability for the HBG subscale (ρ = 0.76), a moderately high stability for the NSC subscale (ρ = 0.63) and excellent stability for the HH subscale (ρ = 0.88). These results support the robustness of the instrument for use in longitudinal studies and for clinical purposes. The analysis concerning parental characteristics contributed relevant information for clinical practice. Although in our study mothers had slightly higher scores for FoH compared to fathers, the difference was only statistically significant in one of the worry subscales (helplessness regarding hypoglycemia). This was consistent with the literature, as mothers have commonly reported higher levels of anxiety in relation to hypoglycemia in their children. Several previous studies have yielded similar findings20–23 in reporting higher FoH scores in mothers (possibly because mothers are frequently the primary caregiver), while our findings were also in agreement with those of other studies that did not find significant differences based on sex.6 In any case, health care providers must be aware of this tendency and assess the level of fear individually in both fathers and mothers. Another salient finding was the association of parental educational attainment with parental FoH. A possible explanation is that a higher level of education facilitates a better understanding of the disease and health care recommendations, resulting in increased parental confidence and autonomy in the management of diabetes in their children. Our results support the hypothesis proposed by some authors that the educational attainment of the primary caregiver may act as a moderator in fear questionnaire scores.11,22 Thus, in the context of diabetes care, it would be appropriate to adapt educational interventions in relation to this factor, ensuring that parents with lower educational attainment receive explanations in simple and understandable language, reinforcing key learning points regarding blood glucose control and even offering additional training sessions focused on the management of hypoglycemic episodes. This would empower those caregivers that face greater challenges, reducing their anxiety by improving their understanding and practical skills. In agreement with previous studies, we found a significant association between the parental fear of hypoglycemia and glycemic control in the child. Parents with more severe FoH tended to have children with poorer metabolic outcomes (higher levels of HbA1c). This supports the hypothesis that excessive fear may interfere with the optimal management of diabetes, possibly due to overprotective or avoidant behaviors that result in sustained hyperglycemia. Other studies have reported this association,6,11,21 demonstrating that greater parental fear correlates to poorer disease control. Recognizing the influence of parental FoH on their children’s glycemic control underscores the importance of managing this fear with a psychological approach: reducing FoH could indirectly contribute to improving glycemic control in the pediatric population. Last but not least, we ought to highlight the observed association with the family history of diabetes. Although no previous studies have found a link between having relatives with T1D and FoH, in our sample, parents with a positive family history had higher FoH scores compared to those without it, with significant differences in the scores for the total scale and the worry about social consequences subscale. A possible explanation is that caregivers who have experienced diabetes up close (having lived with diabetic relatives) are more aware of the risks and complications of the disease, which could intensify their fear of hypoglycemic events. This novel finding suggests that clinicians should be particularly mindful in the case of families with a history of diabetes, keeping in mind that they may develop greater FoH and, consequently, providing additional support and guidance from diagnosis to help mitigate it.

LimitationsIn the first place, since the study was conducted in two hospitals, it would be useful to include centers in other geographical areas to assess the applicability of the questionnaire in different contexts. In addition, the prospective data collection relied on the parental recall, which may have resulted in underestimation of the incidence of hypoglycemic episodes, especially those that are asymptomatic or unconfirmed. Finally, although we used a validated questionnaire to measure parental worry, the use of additional instruments (eg, assessments of adherence to treatment or quality of life) and a larger sample size would allow establishment of more robust clinical relationships.

ConclusionWe conducted a study to validate the Spanish version of the HFS-P, which yielded a questionnaire with excellent psychometric properties. We have demonstrated the feasibility, validity (content, construct and criterion), high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability of the Spanish version. Therefore, it is now available as a valid, standardized and reliable instrument to detect the fear of hypoglycemia in parents and caregivers of children with T1D. The use of this questionnaire in pediatric diabetes clinics will allow early identification of families with elevated FoH and implementation of specific support and education interventions aimed at reducing this fear and, potentially, optimizing diabetes control in the pediatric population.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.