Infants under 28 days of age are an especially vulnerable population, and data regarding coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in this age group are scarce. We aimed to describe the clinical course and the probability of severe illness in a series of infants admitted to hospital with confirmed infection by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

We performed a multicentre, observational and descriptive study in 5 secondary and tertiary care hospitals in Spain between March 1 and June 3, 2020. We included hospitalised infants aged 28 days and younger with a positive result of in the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for detection SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal samples.

We recorded the sex, age and weight of the patients, the symptoms, reason for admission, history of chronic disease or treatment with immunomodulators, length of stay, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), treatment received and laboratory findings.

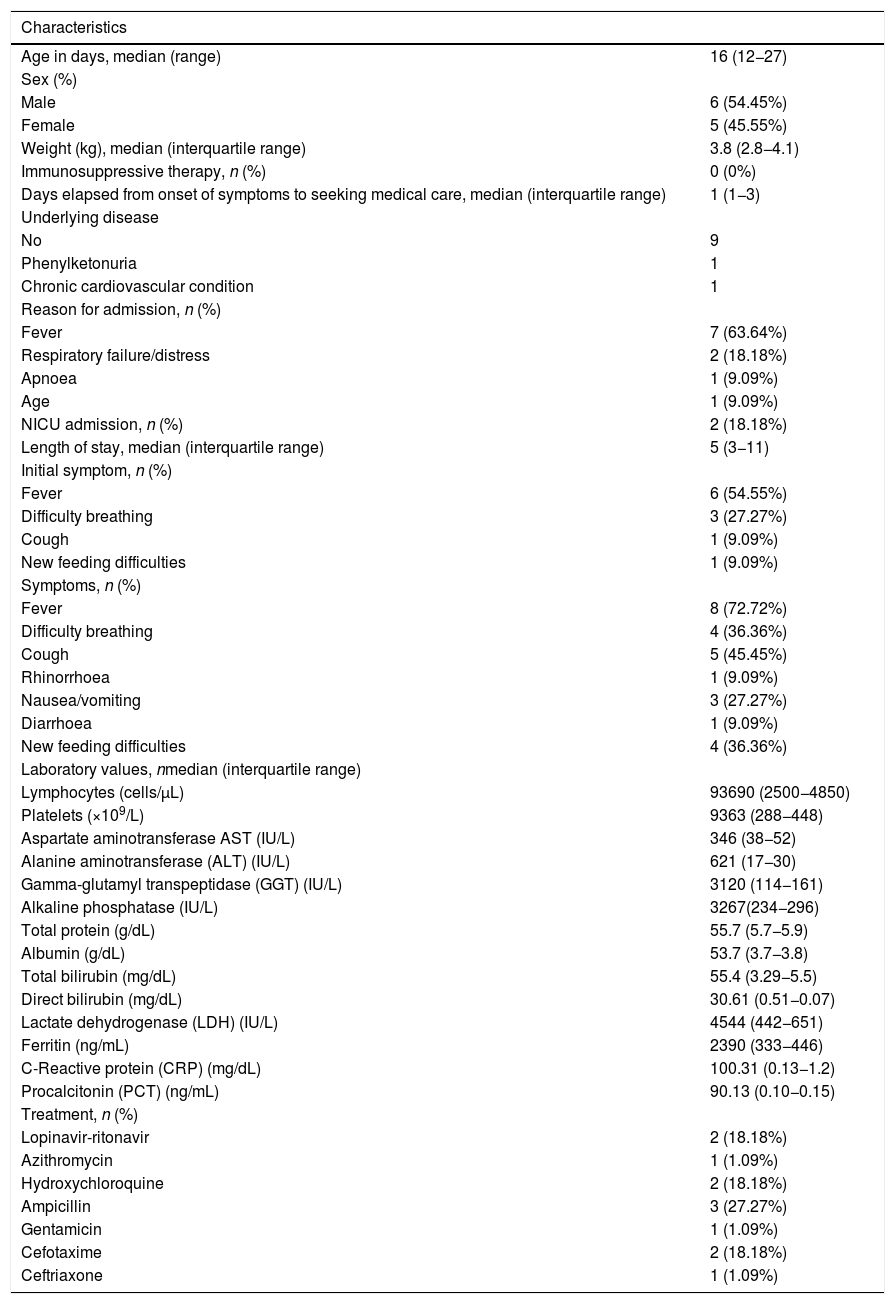

The sample included 11 patients aged 12 to 27 days. Only 2 patients required admission to the NICU (18%), 1 of who had a chronic cardiovascular disease. Table 1 summarises epidemiological and clinical data for the sample.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics, laboratory test results and received treatment in the study sample.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age in days, median (range) | 16 (12−27) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Male | 6 (54.45%) |

| Female | 5 (45.55%) |

| Weight (kg), median (interquartile range) | 3.8 (2.8−4.1) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Days elapsed from onset of symptoms to seeking medical care, median (interquartile range) | 1 (1−3) |

| Underlying disease | |

| No | 9 |

| Phenylketonuria | 1 |

| Chronic cardiovascular condition | 1 |

| Reason for admission, n (%) | |

| Fever | 7 (63.64%) |

| Respiratory failure/distress | 2 (18.18%) |

| Apnoea | 1 (9.09%) |

| Age | 1 (9.09%) |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 2 (18.18%) |

| Length of stay, median (interquartile range) | 5 (3−11) |

| Initial symptom, n (%) | |

| Fever | 6 (54.55%) |

| Difficulty breathing | 3 (27.27%) |

| Cough | 1 (9.09%) |

| New feeding difficulties | 1 (9.09%) |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Fever | 8 (72.72%) |

| Difficulty breathing | 4 (36.36%) |

| Cough | 5 (45.45%) |

| Rhinorrhoea | 1 (9.09%) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 3 (27.27%) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (9.09%) |

| New feeding difficulties | 4 (36.36%) |

| Laboratory values, nmedian (interquartile range) | |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 93690 (2500−4850) |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 9363 (288−448) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase AST (IU/L) | 346 (38−52) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (IU/L) | 621 (17−30) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) (IU/L) | 3120 (114−161) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 3267(234−296) |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 55.7 (5.7−5.9) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 53.7 (3.7−3.8) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 55.4 (3.29−5.5) |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 30.61 (0.51−0.07) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (IU/L) | 4544 (442−651) |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 2390 (333−446) |

| C-Reactive protein (CRP) (mg/dL) | 100.31 (0.13−1.2) |

| Procalcitonin (PCT) (ng/mL) | 90.13 (0.10−0.15) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| Lopinavir-ritonavir | 2 (18.18%) |

| Azithromycin | 1 (1.09%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 2 (18.18%) |

| Ampicillin | 3 (27.27%) |

| Gentamicin | 1 (1.09%) |

| Cefotaxime | 2 (18.18%) |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 (1.09%) |

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

The highest observed values of aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase were 54 IU/L and 42 IU/L, respectively. One infant had hyperbilirubinaemia (total bilirubin 11.3mg/dL, conjugated bilirubin 0.7mg/dL). Three patients had high levels of C-reactive protein (CPR) and/or procalcitonin (PCT). In 1 patient, penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus agalactiae was isolated from blood culture.

When it came to the use of the options currently available for treatment of COVID-19, only the 2 infants that were admitted to the NICU received lopinavir-ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine, and 1 of them was also treated with azithromycin.

The most frequent symptom was fever, followed by respiratory symptoms like cough and breathing difficulty, in agreement with previously published paediatric reports.1,2 It is worth noting that more than one third of the infants showed gastrointestinal symptoms like feeding difficulties, nausea/vomiting or diarrhoea. These features, previously thought to be rare, have been reported with increasing frequency during the pandemic. The virus binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, expressed in the pulmonary epithelium but also throughout the gut, which would explain the gastrointestinal symptoms observed in patients with COVID-19.

The reason for admission in 3 infants, who presented with symptoms like respiratory failure and apnoea, was presumed to be related to COVID-19. The rest were hospitalized due to the presence of fever, as most hospital protocols indicate admission of febrile neonates. Only 2 infants required intensive care, 1 of who had an underlying condition. These data suggest that most infants with SARS-CoV-2 have mild presentations, especially if they were previously healthy.

Unfortunately, the limited evidence currently available on the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in young infants precludes direct comparison with other sources. Zhang et al. identified 4 neonates with SARS-CoV-2 infection, none of who had severe complications.3 Zeng et al. published a case series of 3 neonates with SARS-CoV-2 infection, all of who presented with respiratory symptoms. One of them required mechanical ventilation but his symptoms may have been caused by prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis.4 Alonso et al. reported the first case of neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infection in Spain. The only symptom in this patient was intermittent polypnea, which lasted for 24h and required no specific treatment.5 McLaren et al. published a case series of febrile infants with SARS-CoV-2 infection that included 3 patients under 28 days. None of them had poor outcomes.

None of the infants in our study exhibited significant abnormalities in any of the blood chemistry tests. One had a positive blood culture (penicillin-susceptible S. Agalactiae) and only 3 had elevation of CRP and/or PCT. This suggests that secondary bacterial infection or bacteraemia, though uncommon, should always be ruled out in symptomatic patients.

There is no clear evidence of vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Maternal SARS-CoV-2 status and the timing of detection of the virus by RT-PCR in newborns (48−72h after delivery) need to be considered to determine the type of transmission. We assumed that transmission in our patients was horizontal because the positive result for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal samples occurred at least 12 days after delivery.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the sample size was relatively small. Second, we were unable to ensure that the health records were complete for infants that were retrospectively identified. Third, some of the laboratory tests were not performed in all patients.

In conclusion, infants under 28 days of age are also susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The large majority of these patients had milder symptoms and more favourable outcomes compared to older children and adults. However, some infants may also require intensive care. For this reason, providers must consider the possibility of COVID-19 in infants presenting with fever and respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, screen pregnant women, implement strict infection control measures and closely monitor neonates at risk.

Please cite this article as: Velasco Rodríguez-Belvís M, Medina Benítez E, García Tirado D, Herrero Álvarez M, González Jiménez D. Infección por SARS-CoV-2 en neonatos menores de 28 días. Serie de casos multicéntrica. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96:149–151.