The incidence of pulmonary thromboembolism (PE) currently exhibits an upward trend in the pediatric age group,1 and, while it is still rare in children, it is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. The estimated incidence in some case series ranges from 2 to 6 cases per 10 000 hospital discharges, and it is greater in adolescents with a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).2 Its low frequency, combined with an atypical presentation and the absence of validated scores for children, results in delays in diagnosis of approximately one week on average.3 We describe the two cases diagnosed in our hospital.

Case 1. Girl aged 12 years admitted to a regional hospital with pneumonia due to coinfection with influenza B virus and SARS-CoV-2. She was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of our hospital due to bacterial superinfection with elevation of acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein [CPR], 313mg/dL and procalcitonin [PCT], 11ng/mL) and development of parapneumonic effusion. At the time of admission to our hospital, the patient met the criteria for sepsis and required noninvasive ventilation and vasoactive drugs, so treatment was initiated with intravenous cefotaxime. She also received prophylactic antithrombotic treatment with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (enoxaparin) at a dose of 0.5mg/kg/12h due to the associated risk factors: central venous catheter (CVC), being bedridden and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite prophylaxis, 5 days after admission, an ultrasound scan revealed catheter-related right iliac vein thrombosis.

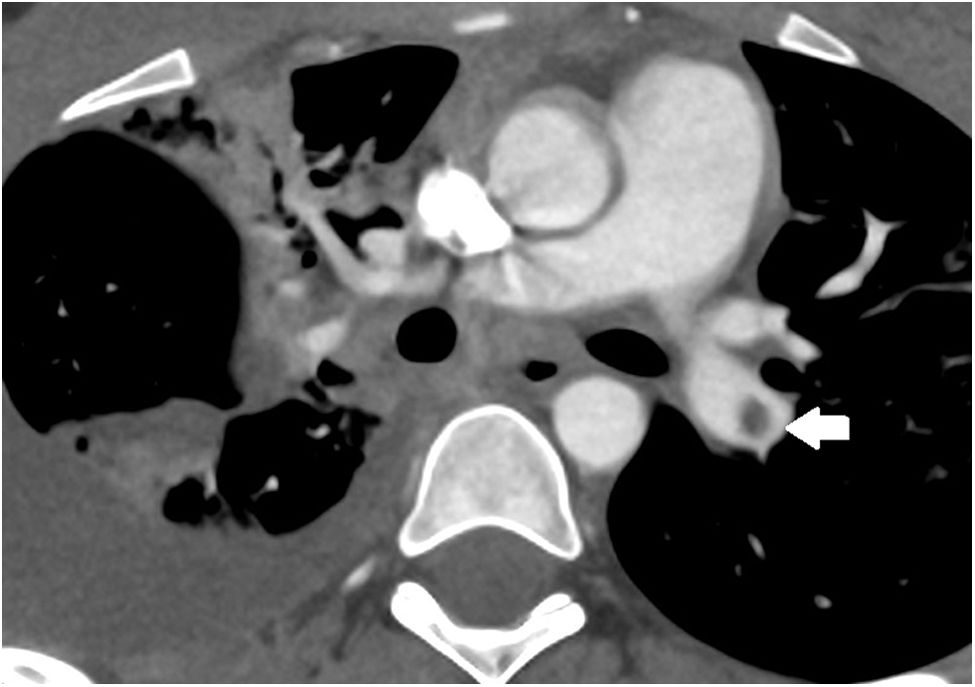

The patient showed clinical improvement with a reduction in oxygen requirements, but the chest CT scan performed to assess pleural effusion detected PE in the left pulmonary artery (Fig. 1). Since the embolism was not clinically significant, the dose of enoxaparin was increased to a therapeutic dose (1mg/kg/12h to maintain antifactory Xa levels in the range of 0.3–1U/mL) for three months, after which the follow-up CT scan confirmed the resolution of the PE.

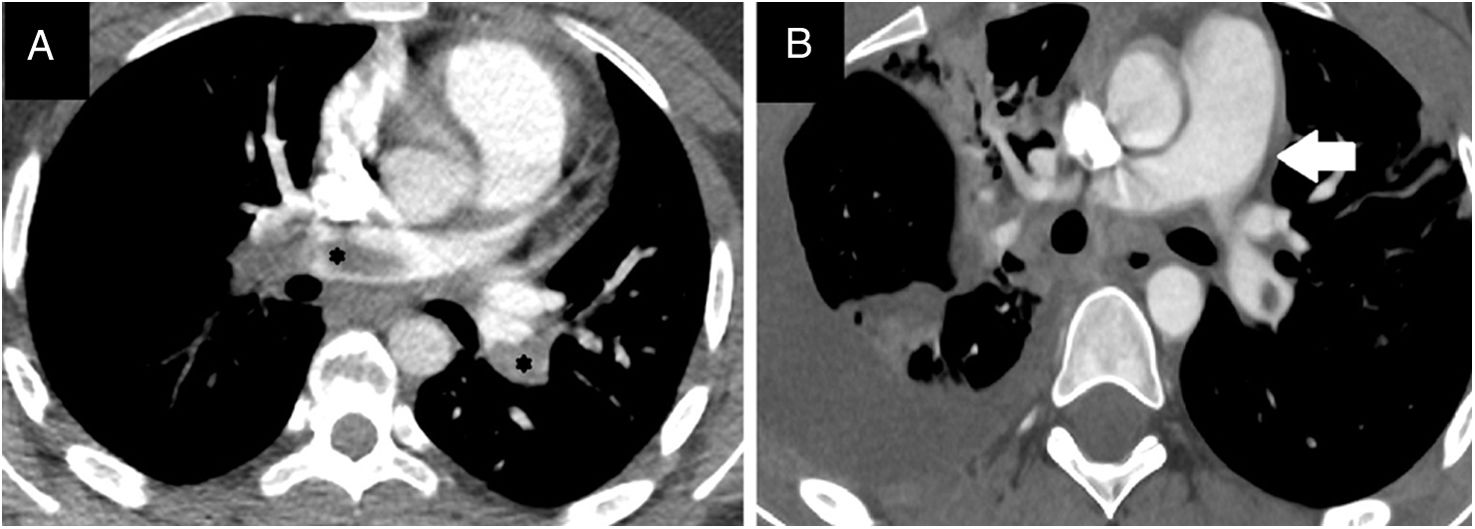

Case 2. Female adolescent aged 14 years with morbid obesity (weight, 115kg; BMI, 38) assessed in the emergency department for dyspnea of abrupt onset associated with chest pain and syncope. She had tachycardia (160bpm) with an arterial blood pressure at the limit of normal for age (105/50) and did not require vasoactive drugs. The relevant recent history was having been bedridden the previous week due to a knee sprain without receiving antithrombotic prophylaxis, leading to development of DVT in the left popliteal vein. The salient findings of blood tests were a D-dimer level of 13 700ng/mL and elevation of troponin levels to up to 506ng/L and of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide to 589pg/mL. The CT angiogram confirmed bilateral PE (Fig. 2) with signs of right ventricular (RV) overload, which was also assessed by means of echocardiography (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion [TAPSE], 1.6cm; normal range, 1.9–2.7cm). She was transferred to our PICU, where treatment was initiated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) for anticoagulation and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) at a dose of 25mg for thrombolysis, with progressive clinical improvement over the next 24h. Intravenous infusion of UFH was maintained for four days (adjusting the dose as needed to maintain anti-Xa levels in the 0.3–0.7U/mL range) and subsequently switched to subcutaneous HBPM for three weeks followed by acenocoumarol for 6 months, maintaining the international normalized ratio (INR) between 2 and 3. The follow-up CT scan showed resolution after completion of treatment.

The risk stratification for PEs is generally carried out by means of the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI), an instrument that is not yet validated in the pediatric population and that assesses aspects characteristic of adult disease such as heart failure or chronic lung disease and cancer. Thus, the authors of a review published in CHEST in 20223 recommended stratifying risk based on hemodynamic status: high risk for patients requiring vasoactive drugs, intermediate risk in the presence of RV failure without hypotension and low risk when none of the aforementioned criteria are met.

The therapeutic approach depends on the risk stratification. As we saw in case 1, anticoagulation with HBPM is sufficient in hemodynamically stable patients (low risk).3 However, there is controversy regarding the appropriate approach in patients with intermediate or high risk, as anticoagulation alone could result in pulmonary hypertension in the long term but thrombolysis carries a risk of intracranial hemorrhage of up to 2%.4 In consequence, in case 2 (RV strain without hypotension: intermediate risk) the chosen approach was to administer a “safe dose” of rtPA, that is, half the standard dose used for thrombolysis, administered intravenously over 2h. Although this approach is only supported by evidence from case series,3,5 it appears to be effective in adult patients at low risk of severe bleeding.

We believe that multidisciplinary management is of the essence, making decisions in consultation with adult intensive care, cardiology and radiology specialists, given their expertise in the disease. In light of the increasing incidence in the pediatric population, further research should be conducted to assess the particular characteristics of PE in this age group and validate diagnostic and risk stratification instruments, thus enabling the development of clinical guidelines adapted to pediatric patients.