Lymphadenopathy is a frequent finding in the pediatric physical examination. The most prevalent etiology is inflammation secondary to a benign and self-limiting condition, usually infection. The differential diagnosis must include other conditions, including malignancies.1

Approximately 4% of chronic lymphadenopathy biopsy specimens exhibit features compatible with a condition known as progressive transformation of germinal centers (PTGC) that is not well understood.2 It is a reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of unknown clinical significance that may precede, follow or develop simultaneously with certain cancers, especially nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL),3,4 so its characterization is important.

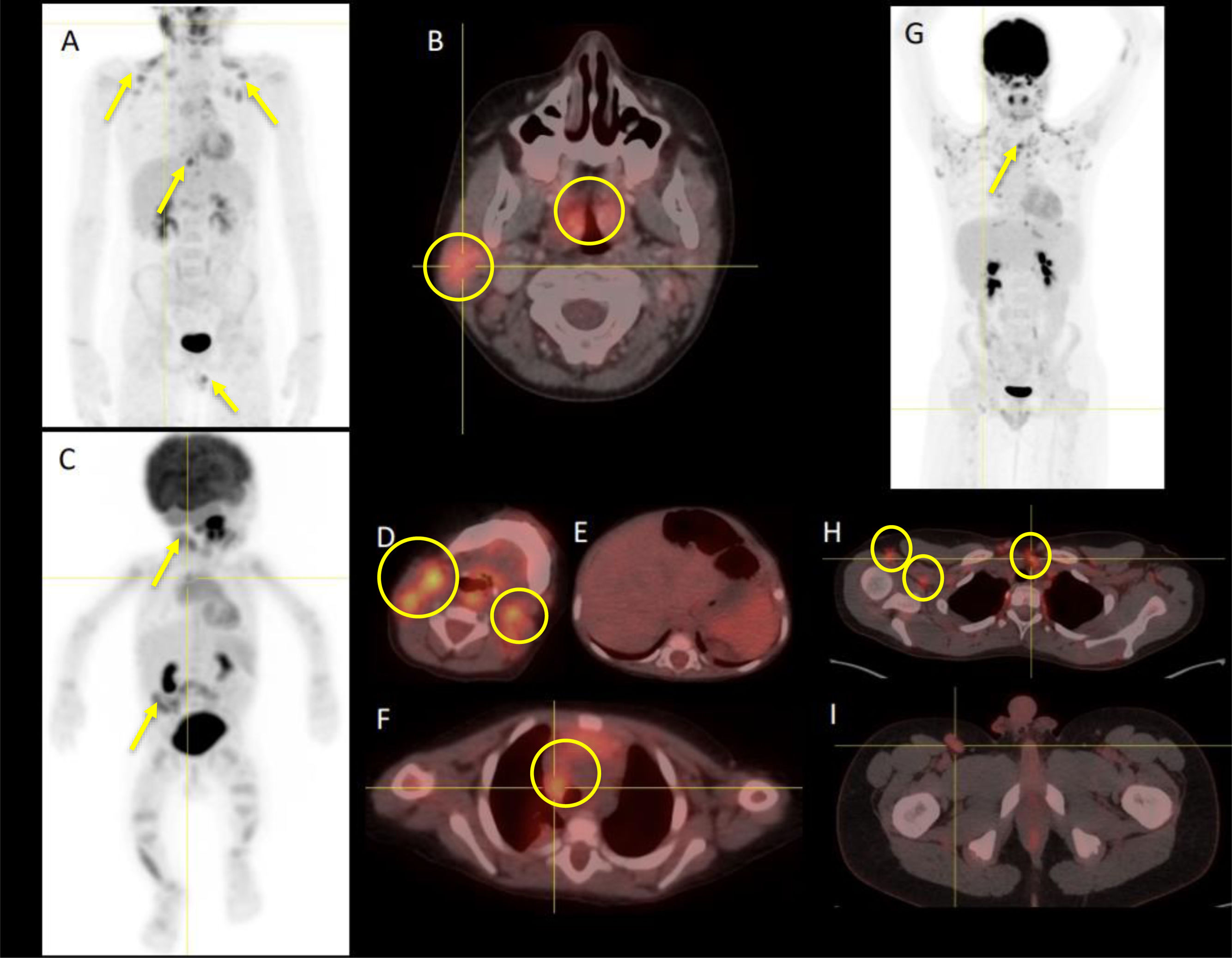

Sonography may be very useful in the differential diagnosis, although in some cases its findings overlap those of inflammatory or infectious diseases. Some authors have also suggested the use of [18F]-fluoro-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), although its routine use is controversial on account of the exposure to ionizing radiation and a tracer uptake pattern that is similar to that found in lymphomas.5

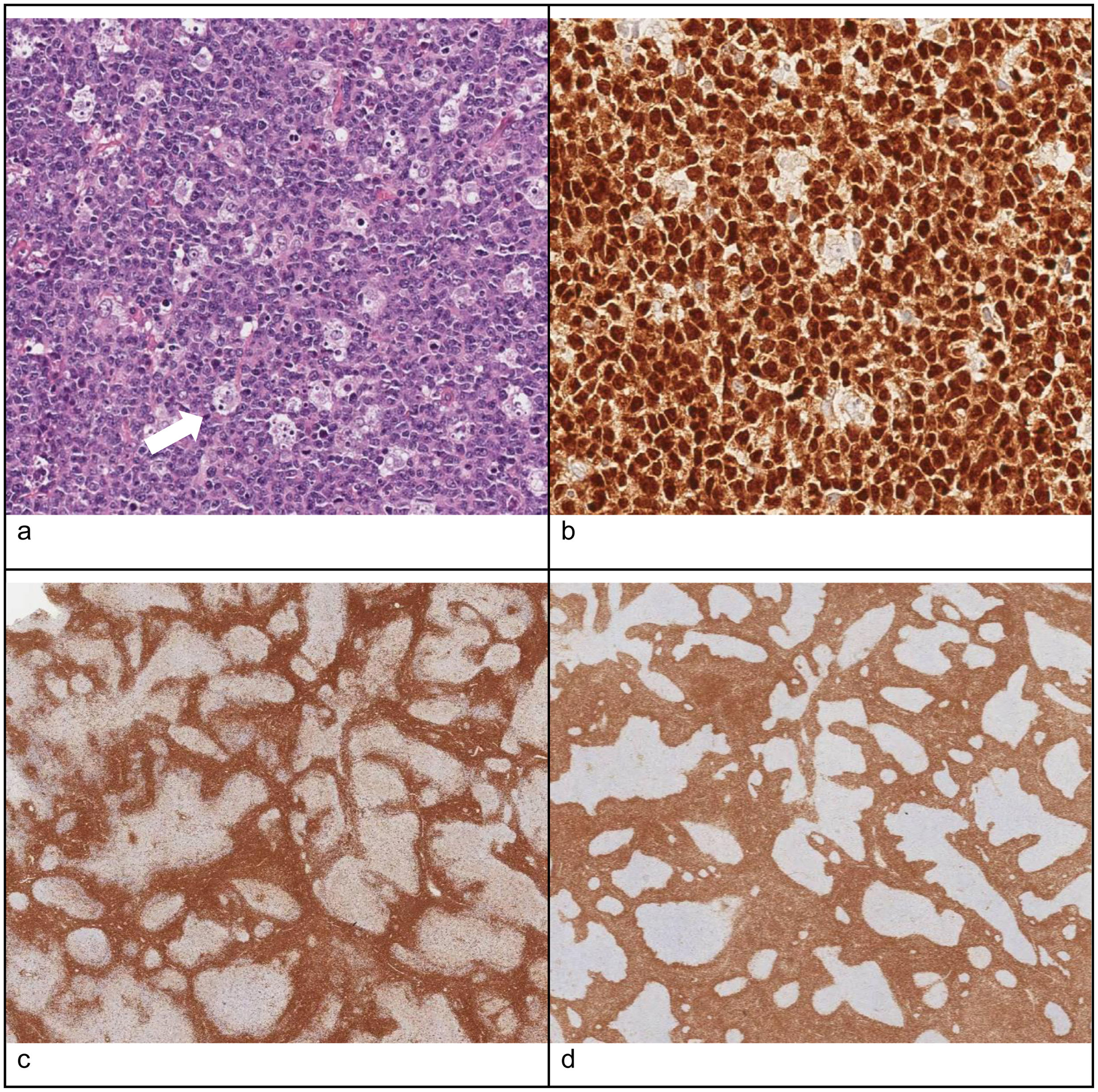

The definitive diagnosis is based on the histological examination, in which PTGC is characterized by the presence of very large reactive follicles composed of B cells in the mantle zone, centroblasts and follicular dendritic cells that migrate toward the residual germinal centers. Typically, the margins between the mantle and the germinal center are poorly defined2–4 (Fig. 1).

Histological features of a lymph node biopsy specimen compatible with PTGC: (a) hematoxylin–eosin staining: follicles with enlarged germinal centers surrounded by eccentric mantle zone layers with poorly defined margins; (b) PAX5 immunostaining: nuclear staining in B cells in the mantle zone, useful to differentiate normal lymphoid tissue and some types of Hodgkin lymphoma; (c) CD3 immunostaining: abundance of mature T cells in the mantle zone; (d) BCL2 immunostaining: positive expression in mantle and T cells but not in germinal centers, contrary to follicular lymphoma (in which germinal centers are BCL2+).

Its chronological association with lymphoma has motivated prolonged monitoring, frequent imaging tests and repeated biopsies in patients with persistent clinically significant lymphadenopathy. In Spain, no register has been established to survey its prevalence and there are very few publications on the subject focused on the pediatric age group.

With the aim of expanding our knowledge of this disease, we analyzed data on the epidemiological and clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of patients aged 1–16 years with PTGC managed in a tertiary care hospital over a 10-year period (2013–2023).

The sample included 12 patients with a diagnosis of PTGC (10 male, 2 female). The mean age at diagnosis was 8.7 years (7 months–13 years). The location of lymphadenopathy was cervical in four, inguinal in three, axillary in 2, supraclavicular in one, mediastinal in one and preauricular in one. The mean size of lymph nodes with clinically significant enlargement was 3 cm (1–4 cm).

The mean time elapsed from onset to initiation of a targeted evaluation was two months and three weeks (24 h–8 months).

The initial evaluation included an ultrasound scan in every patient, with findings that overlapped those in malignant lymphoproliferative disorders. A PET/CT scan was performed in 4 patients (33%) and showed significant activity with a mean maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 4.5 g/mL (Fig. 2). In all patients, the diagnosis was confirmed by histological examination.

Three patients had a recent history of resolved infectious disease (respiratory tract infection, adenoid phlegmon and mononucleosis). Serologic tests were performed in 10 of the 12 patients (83%) and yielded a positive result for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-specific immunoglobulin M in two of them. We found no evidence of a causal relationship between EBV infection and PTGC in the previous literature.

Three patients had systemic symptoms at diagnosis (fever, arthralgia and night sweats) unrelated to infection or a tumor.

Twenty-five percent of the patients (n = 4) had underlying immune disorders (IRAK deficiency, neurofibromatosis type I, hereditary spherocytosis and immune thrombocytopenic purpura), which was consistent with previous studies and is not associated to poorer outcomes.3 Three of these patients continued to have clinically significant lymphadenopathy throughout the follow-up.

Two patients had a previous history of oncological disease: one of classic Hodgkin lymphoma, in remission for the past 4 years, and another of nodal marginal zone lymphoma, also in remission for 4 years. Although some authors have suggested the use of rituximab for treatment of PTGC in patients with a history of lymphoid neoplasms,6 in this case series, these patients did not receive any additional treatment and both had favorable outcomes. None of the patients developed lymphoid neoplasms during the follow-up.

Progressive transformation of germinal centers is usually characterized by slow growth and a high rate of recurrence. The optimal frequency of follow-up has not been clearly established.6 In our study, four of the 12 patients (33%) had persistently enlarged lymph nodes greater than 1 cm with the same clinical and sonographic characteristics. Two of the 12 (16.6%) underwent a second biopsy that confirmed the persistence of the histological abnormalities. The mean duration of follow-up was 36 months (5–84) and all patients had favorable outcomes.

In conclusion, PTGCs are a poorly understood condition that may be associated with oncological diseases. In our small sample, the course of disease was very favorable. Clinical monitoring may be sufficient, reserving the use of additional tests for cases with significant changes in the examination.

Previous presentation: this study was presented as a poster at the 2023 Congress of the Sociedad Española de Oncología Pediátrica.