Pediatric palliative care (PPC) is an approach to the comprehensive care to children with life-threatening and life-limiting illnesses and their families. The availability of PPC resources in Spain has increased in recent year, although there are still aspects in need of improvement, especially as regards the composition of care teams (multidisciplinary approach) and offering 24/7 coverage.1,2

A recently published study analysed the availability of PPC resources for pediatric oncology centers in Europe.3 All pediatric oncology centers in Europe were eligible for participation and the authors asked that the providers most familiar with palliative care services for pediatric oncology in each center complete the survey, which had been previously validated online. A single response was included per oncology unit. After publishing the original manuscript, the authors shared the data corresponding to Spain, which were analysed by the palliative care coordinator of the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátrica (SEHOP, Spanish Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology) and two members of the Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos Pediátricos (PEDPAL, Spanish Society of Pediatric Palliative Care). The analysis focused on the current availability of PPC resources as well as perceived barriers to PPC.

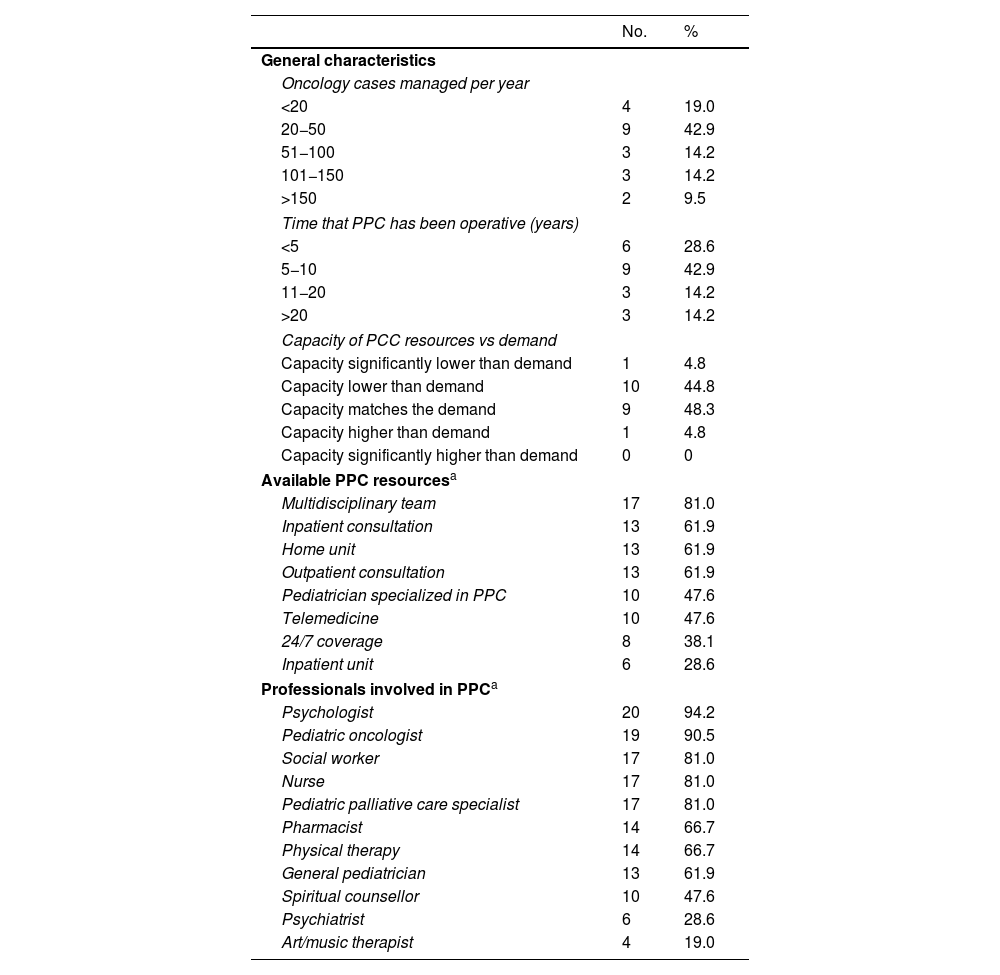

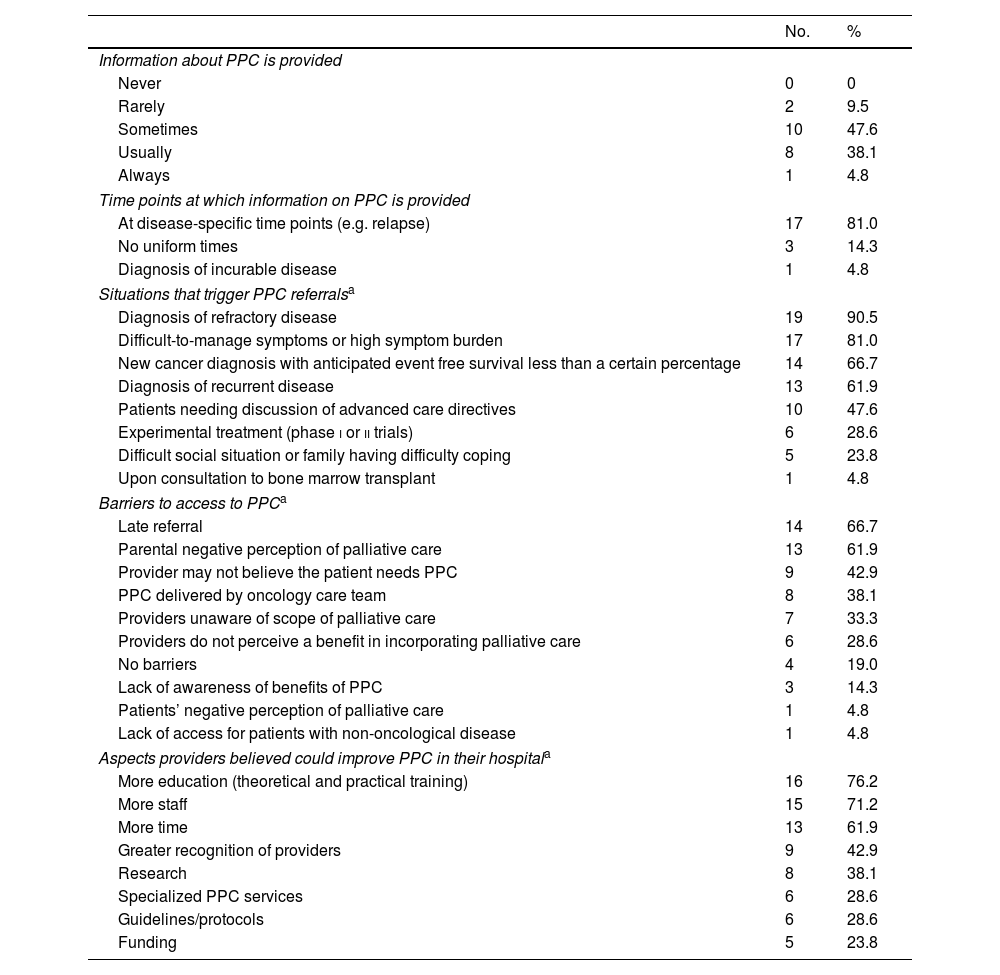

Of the 43 hospitals in Spain with pediatric oncology departments, 21 participated in the study (response rate, 48.8%; Table 1). One center (4.8% in Spain vs 3% in all of Europe) did not provide any form of palliative care, while 76.2% offered specialized PPC services (compared to 64.6% in Europe) and 19.1% had some other form of PPC resources (compared to 29% in Europe). Based on the responses, there was high availability of resources in terms of the professionals involved; however, almost half of respondents reported that the PPC capacity of their centers was insufficient to meet the actual demand. The main perceived barrier to the delivery of PPC (Table 2) was late referral, which was consistent with the fact that diagnosis of refractory disease was the main reason for referral. Another significant barrier, reported by 40% of centers, was that providers may not consider initiation of specialized PPC necessary for their patients. However, 76.2% of respondents considered that more education/training would increase delivery of PPC in their centers.

Availability of pediatric palliative care resources in oncology centers.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | ||

| Oncology cases managed per year | ||

| <20 | 4 | 19.0 |

| 20−50 | 9 | 42.9 |

| 51−100 | 3 | 14.2 |

| 101−150 | 3 | 14.2 |

| >150 | 2 | 9.5 |

| Time that PPC has been operative (years) | ||

| <5 | 6 | 28.6 |

| 5−10 | 9 | 42.9 |

| 11−20 | 3 | 14.2 |

| >20 | 3 | 14.2 |

| Capacity of PCC resources vs demand | ||

| Capacity significantly lower than demand | 1 | 4.8 |

| Capacity lower than demand | 10 | 44.8 |

| Capacity matches the demand | 9 | 48.3 |

| Capacity higher than demand | 1 | 4.8 |

| Capacity significantly higher than demand | 0 | 0 |

| Available PPC resourcesa | ||

| Multidisciplinary team | 17 | 81.0 |

| Inpatient consultation | 13 | 61.9 |

| Home unit | 13 | 61.9 |

| Outpatient consultation | 13 | 61.9 |

| Pediatrician specialized in PPC | 10 | 47.6 |

| Telemedicine | 10 | 47.6 |

| 24/7 coverage | 8 | 38.1 |

| Inpatient unit | 6 | 28.6 |

| Professionals involved in PPCa | ||

| Psychologist | 20 | 94.2 |

| Pediatric oncologist | 19 | 90.5 |

| Social worker | 17 | 81.0 |

| Nurse | 17 | 81.0 |

| Pediatric palliative care specialist | 17 | 81.0 |

| Pharmacist | 14 | 66.7 |

| Physical therapy | 14 | 66.7 |

| General pediatrician | 13 | 61.9 |

| Spiritual counsellor | 10 | 47.6 |

| Psychiatrist | 6 | 28.6 |

| Art/music therapist | 4 | 19.0 |

Information and communication about pediatric palliative care and barriers to access.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Information about PPC is provided | ||

| Never | 0 | 0 |

| Rarely | 2 | 9.5 |

| Sometimes | 10 | 47.6 |

| Usually | 8 | 38.1 |

| Always | 1 | 4.8 |

| Time points at which information on PPC is provided | ||

| At disease-specific time points (e.g. relapse) | 17 | 81.0 |

| No uniform times | 3 | 14.3 |

| Diagnosis of incurable disease | 1 | 4.8 |

| Situations that trigger PPC referralsa | ||

| Diagnosis of refractory disease | 19 | 90.5 |

| Difficult-to-manage symptoms or high symptom burden | 17 | 81.0 |

| New cancer diagnosis with anticipated event free survival less than a certain percentage | 14 | 66.7 |

| Diagnosis of recurrent disease | 13 | 61.9 |

| Patients needing discussion of advanced care directives | 10 | 47.6 |

| Experimental treatment (phase i or ii trials) | 6 | 28.6 |

| Difficult social situation or family having difficulty coping | 5 | 23.8 |

| Upon consultation to bone marrow transplant | 1 | 4.8 |

| Barriers to access to PPCa | ||

| Late referral | 14 | 66.7 |

| Parental negative perception of palliative care | 13 | 61.9 |

| Provider may not believe the patient needs PPC | 9 | 42.9 |

| PPC delivered by oncology care team | 8 | 38.1 |

| Providers unaware of scope of palliative care | 7 | 33.3 |

| Providers do not perceive a benefit in incorporating palliative care | 6 | 28.6 |

| No barriers | 4 | 19.0 |

| Lack of awareness of benefits of PPC | 3 | 14.3 |

| Patients’ negative perception of palliative care | 1 | 4.8 |

| Lack of access for patients with non-oncological disease | 1 | 4.8 |

| Aspects providers believed could improve PPC in their hospitala | ||

| More education (theoretical and practical training) | 16 | 76.2 |

| More staff | 15 | 71.2 |

| More time | 13 | 61.9 |

| Greater recognition of providers | 9 | 42.9 |

| Research | 8 | 38.1 |

| Specialized PPC services | 6 | 28.6 |

| Guidelines/protocols | 6 | 28.6 |

| Funding | 5 | 23.8 |

After reviewing the data and consulting with members of the PEDPAL, we determined that some findings of the study may not accurately reflect the current availability of PPC services in Spain. For instance, six centers reported having dedicated PPC beds on site, when only three units actually have this resource. Similarly, 10 of the 21 respondents reported that a spiritual counselor was available, when in fact only two PPC teams in Spain include this type of professional, which demonstrates that while hospitals may have such a provider on staff, the provider may not be part of the PPC team. Given the difficulty involved in interpreting these data, we did not make further comparisons with the original article.

There are several possible factors that may explain these discrepancies. First of all, the PEDPAL, as a scientific society, relies on its members to obtain data, and therefore it may have underestimated the availability of specific resources. However, we ought to take into account that the members of the PEDPAL are actively involved in the review of the National Strategy for Pediatric Palliative Care, an initiative of the Spanish Ministry of Health.1,2 Secondly, in some regions, such as Madrid, a single PPC team may provide coverage for several oncology centers. Still, we cannot rule out the possibility that oncology centers may be assessing available PPC resources inaccurately. While the questionnaire asked about specific PPC resources, respondents may have included oncology resources in their responses due to the integration of PPC and oncology services in some centers.4

Several data suggest that in a significant number of cases, provision of PPC is limited to end-of-life care and in some cases is perceived as redundant in relation to the services that can be provided by oncology care teams. However, at the same time, there is a demand for more training, more staff and more time in keeping with the strategic lines outlined in the evaluation of the National Palliative Care Strategy.1 Pediatric palliative care should be provided from diagnosis of a life-threatening or life-limiting condition, finding a way to weave in generalized PPC services through flexible care delivery models.5 The inclusion of generalized PPC in oncology departments or units and of specialized PPC in specific scenarios is not optional, but a standard at both the domestic and international levels.2,6 Recognizing existing barriers may be the first step required to improve pediatric palliative care.

While it is important to have generalized PPC resources in all units or departments that treat patients with life-limiting illnesses, such as cancer, the role of specialized PPC resources should not be underestimated. Although the conclusions of the survey are not definitive, its findings highlight the critical need for a collaborative approach to accurately assess specialized PPC resources. Oncologists and other health professionals are essential in the provision of generalized PPC; however, national and international standards emphasize that specialized PPC services should be available to all patients with life-limiting illnesses, including cancer.2,6 Consequently, PEDPAL, in collaboration with the Spanish Ministry of Health, is working on investigating these resources in order to facilitate improved planning of PPC.

FundingThe project in which the data were collected was funded by the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program of the European Union under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 801076, the Swiss Cancer Research (grant KFS-4995-02-2020) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 10001C_182129/1). The work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health of Switzerland. No additional funding was received to conduct the subgroup analysis.