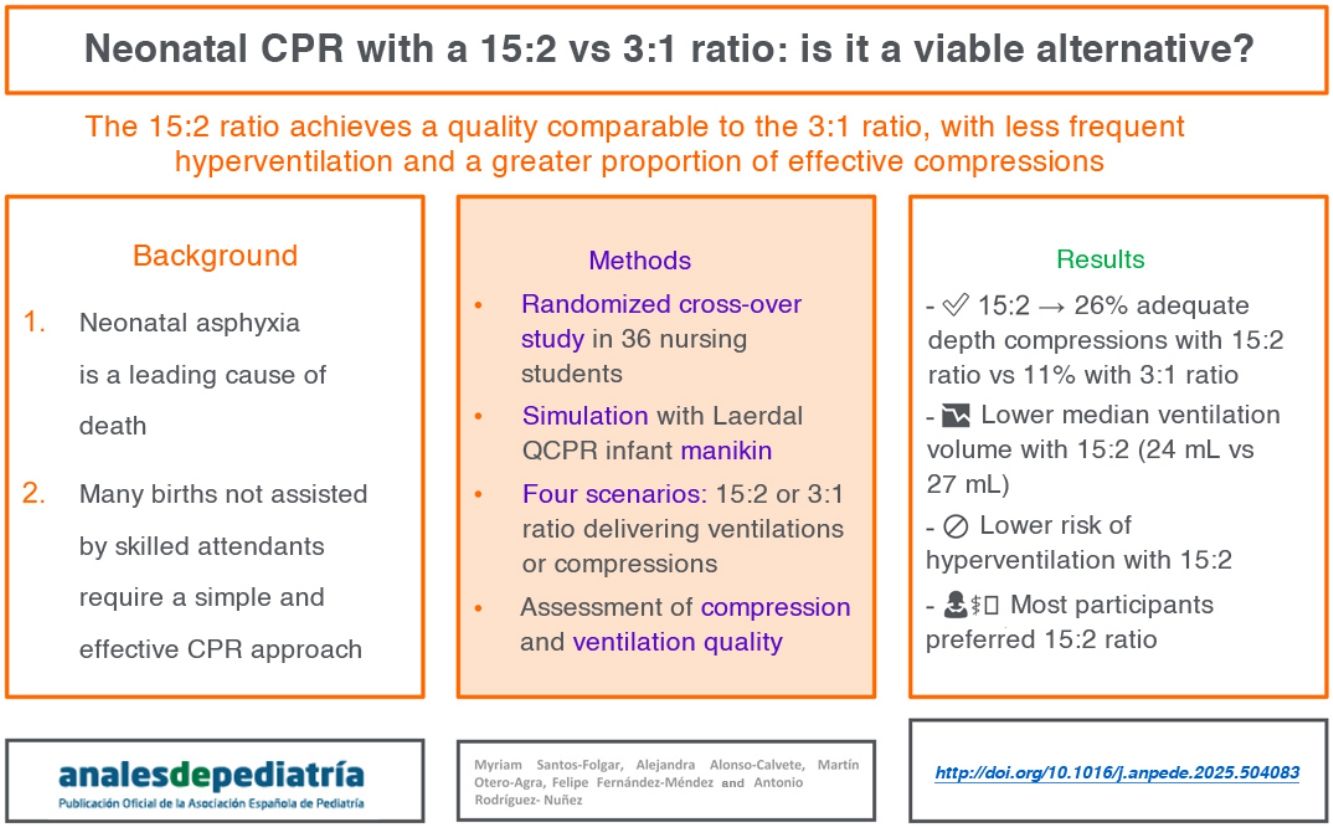

Neonatal asphyxia is a major cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide. Most births in resource-limited settings are not attended by a specialist, so the implementation of a universal (for all children) cardiopulmonary resuscitation technique could be efficient. The aim of this study was to compare the quality of neonatal CPR using compression-to-ventilation ratios of 15:2 versus 3:1.

MethodsA randomized crossover study was conducted with 36 trained nursing students. Neonatal CPR simulations were performed using manikins. Each participant completed four 2-minute CPR simulations, alternating between ventilation and chest compressions using the 15:2 and 3:1 ratios. Rest periods were included to avoid fatigue. Compression and ventilation variables were measured using the Resusci Baby QCPR manikin and SimPad PLUS. We also documented participant preferences.

ResultsWe found a higher percentage of compressions with adequate depth with the 15:2 CPR ratio (26% vs 11%, P = .005). In terms of ventilations, the 3:1 CPR ratio achieved a higher mean tidal volume (27 vs 24 mL, P = .002) a higher mean ventilation rate per minute (32 vs 15, P < .001) and a higher mean minute volume (809 mL/min vs 351 mL/min, P < .001). The proportion of ventilations with an adequate tidal volume was higher for the 15:2 CPR ratio (74% vs 64%, P = .14), although this difference was not statistically significant.

ConclusionsIn a neonatal CPR simulation model, the 15:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio achieved quality parameters comparable to the 3:1 ratio in terms of performance. The implementation of a unified compression:ventilation ratio (15:2) for CPR from birth through childhood could simplify training and improve the effectiveness of neonatal resuscitation, particularly in settings with limited resources for birth care training. Our results, obtained in a simulated environment, support the performance of studies in real patients.

La asfixia es una causa importante de mortalidad y morbilidad neonatal en todo el mundo. La mayoría de los nacimientos en regiones con recursos limitados carecen de asistencia profesional, por lo que podría ser eficiente la aplicación de una técnica universal (para toda la infancia) de reanimación cardiopulmonar. El objetivo de este estudio fue comparar la calidad de la RCP neonatal con ratios compresiones:ventilaciones 15:2 versus 3:1.

MétodosEstudio cruzado aleatorizado con 36 estudiantes del Enfermería entrenados. Se realizaron simulaciones de RCP con maniquíes neonatales. Cada participante completó cuatro simulaciones de 2 minutos de RCP ventilando y comprimiendo: RCP 15:2 y RCP 3:1. Se estableció un período de descanso para evitar la fatiga. Se midieron variables de compresión y ventilación utilizando el maniquí Resusci Baby QCPR y SimPad PLUS. Se recogieron datos sobre las preferencias de los participantes.

ResultadosLa RCP 15:2 mostró un mayor porcentaje de compresiones con profundidad adecuada (26% vs 11%, p = 0.005). En cuanto a las ventilaciones, la RCP 3:1 produjo un mayor volumen tidal medio (27 ml vs 24 ml, p = 0.002), así como un ritmo medio de ventilaciones por minuto superior (32 vs 15, p < 0,001) y un mayor volumen medio minuto (809 ml/min vs 351 ml/min, p < 0,001). Las ventilaciones con volumen tidal adecuado fueron superiores en la RCP 15:2 (74% vs 64%, p = 0,14), aunque esta diferencia no fue estadísticamente significativa.

ConclusionesEn un modelo simulador de RCP neonatal la relación compresiones:ventilaciones RCP 15:2 consigue parámetros de calidad comparables a la 3:1 en términos de calidad. La implementación de una relación compresiones:ventilaciones unificada de RCP desde el nacimiento y a lo largo de la infancia (15:2) podría simplificar la formación y mejorar la efectividad de la reanimación neonatal, especialmente en entornos con recursos de formación de atención al parto limitados. Nuestros resultados en un entorno simulado, apoyan la realización de estudios con pacientes reales.

Neonatal asphyxia is a major cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide.1 Most births in resource-limited settings are not assisted by skilled attendants, which underscores the need to implement an efficient cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) approach.2,3 Although the supplies for neonatal CPR are generally the same regardless of the compression-to-ventilation ratio, implementing a unified (for any age group) resuscitation sequence could potentially simplify the process of CPR training and delivery, thus improving effectiveness in situations in which staff may have less experience or ongoing exposure to protocols and recommendations.

When it comes to pediatric resuscitation, international guidelines (European Resuscitation Council and American Heart Association) recommend a compression-to-ventilation ratio of 15:2 for children and a 3:1 ratio for neonates.4,5 These recommendations are based on expert consensus, but no real-world studies have been conducted comparing the effectiveness of these two ratios. However, there are data from animal models and simulated scenarios suggesting that outcomes of neonatal resuscitation would not be worse with the use of other compression-to-ventilation ratios, so that a 15:2 ratio could be as beneficial as a 3:1 ratio while maintaining the quality of the maneuvers.6,7 Thus, the objective of our study was to compare, under simulated conditions, the quality of neonatal CPR using a compression-to-ventilation ratio of 15:2 vs 3:1.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a randomized crossover simulation study to compare the quality of neonatal CPR using compression-to-ventilation ratios of 15:2 vs 3:1 (Fig. 1).

ParticipantsThirty-six fourth-year nursing students from the School of Nursing of Pontevedra (Universidad de Vigo) participated in the study. Although these are not the professionals who usually perform neonatal resuscitation in real-world clinical practice (CPR is chiefly performed by medical residents or physicians), they had previous training in these maneuvers.

Ninety-two percent of participants were female (n = 33). The median age was 21 years (IQR, 21–22), the median body weight 66 kg (IQR, 58–75) and the median height 166 cm (IQR, 163–171).

All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided written informed consent. The inclusion criterion was having previous training in neonatal CPR. The exclusion criterion was not completing all CPR tests.

The Research Ethics Committee of the Health Care Administration of Galicia (Sergas) determined that formal ethics review was not necessary because thisWhen was a simulation study. In addition, all participants were informed about the study protocol and their right to withdraw from the study at any time, and they signed a written informed consent form in adherence to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study protocolPrior to the simulation, participants underwent training consisting of four 30-minute sessions taught in small groups of 10 people. Each session included a brief 5-minute theoretical explanation and a practical session using infant manikins with real-time feedback (Laerdal Resusci Baby QCPR Wireless with SkillReporter). Both the theoretical and practical training was delivered by a researcher and midwife educator, following the recommendations of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines.4

Participants were assigned at random to perform two neonatal CPR simulations, each lasting two minutes. We established this duration because, according to the neonatal CPR algorithm, intubation should be considered if the heart rate remains below 100 bpm after two minutes of CPR.8

- (a)

15:2 CPR, starting with 5 rescue breaths and continuing with cycles of 15 compressions and 2 ventilations.

- (b)

3:1 CPR, starting with 5 rescue breaths and continuing with cycles of 3 compressions and 1 ventilation.

The protocol for each of these simulations was based on the neonatal resuscitation algorithm recommended by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR),9 international guidelines4,5,10 and the CPR Council of Spain.8 Although the 3:1 recommendations do not include rescue breaths, the study protocol included delivery of five rescue breaths at the beginning to simulate the initial ventilation period, followed by delivery of cycles of compressions and ventilations according to the assigned ratio (15:2 or 3:1).

During the two minutes of CPR, the rescuers did not switch roles. Each participant performed a total of four tests: 15:2 CPR delivering compressions, 15:2 CPR delivering ventilations, 3:1 CPR delivering compressions, and 3:1 CPR delivering ventilations. We analyzed the CPR results for each pair. A 30-minute break was scheduled between tests to avoid the effect of fatigue.

After completing all tests, rescuers reported which ratio they felt allowed them to deliver higher‑quality CPR and which they found most comfortable to perform (subjective perception).

MaterialWe used the Resusci Baby QCPR Wireless manikin with SkillReporter (Laerdal Medical; Stavanger, Norway) and SimPad PLUS with SkillReporter, which allowed us to record the variables of interest during CPR. This manikin was designed to simulate a term neonate, with an approximate weight of 3.450 kg (average: male, 3.4–3.6 kg and female, 3.3–3.5 kg).11 The manikin was placed on an Ohmeda Ohio infant warmer system (Ohmeda [Division of BOC Group]; Columbia, MD, USA).

Compressions were delivered with the two-thumb encircling technique and ventilations were delivered with the Ambu SPUR II neonatal manual resuscitator, with a 300 mL reservoir volume, and the Ambu Baby Face Mask number 0 A (Ballerup, Copenhagen, Denmark). An online metronome (Musicca) was used to keep a rate of 150 compressions per minute.12

Study variablesThe SIMPAD system (Laerdal Medical; Stavanger, Norway) allowed us to record data for compressions, ventilations and overall quality of CPR.

To assess the anthropometric values of infants, we used the growth standards of the World Health Organization.11 We assumed the anthropometric measurements of a term neonate at the 50th percentile.

As regards the feedback thresholds, we set a target range of 16–29 mL (5−8 mL/kg) for tidal volume.13 The target range for minute ventilation (tidal volume × respiratory rate) was 640 mL (16 mL × 40 ventilations/min) to 1740 mL (29 mL × 60 ventilations/min). For the compressions, the target pace set in the SimPad was 120–140 compressions/min. According to the ERC guidelines, the optimal compression depth is one third of the anterior posterior dimension of the chest.13 Therefore, we considered a depth of 29–33 mm indicative of high quality.14,15 However, due to the limitations of the software, which did not allow setting the lower bound below 30 mm, we set an optimal depth range of 30–33 mm.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation variablesCompressions (C): percentage of compressions in the adequate depth range (%), percentage of compressions with adequate two-hand placement (%), percentage of compressions with complete recoil (%), mean compression depth (mm), mean compression rate (compressions/minute).

Ventilations (V): percentage of effective ventilations (reaching the lungs of the manikin) (%); mean tidal volume (mL); percentage of ventilations with adequate tidal volume (%); percentage of ventilations with insufficient tidal volume (%); percentage of ventilations with excessive tidal volume (%); mean ventilation rate (V/min); mean minute volume (mL);

Overall CPR variablesOverall CPR variables: total number of compressions, total number of ventilations, mean duration of ventilations (seconds).

Perception variablesAfter completing all CPR tests, participants completed a brief 3-item questionnaire to report how they perceived their own performance. The three items asked which ratio was considered most appropriate for delivering quality ventilations and quality chest compressions, and which felt most comfortable overall to perform CPR.

Statistical analysisAll analyses were performed using the software package IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21 for Windows (Armonk, NY, USA). We described the qualitative variables as absolute and relative frequencies. For quantitative variables, we used measures of central tendency (median) and dispersion (IQR). To compare CPR simulations, after assessing the normality of the distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test, we used the Student t-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for paired samples. For statistically significant comparisons, we calculated the effect size using the Cohen d or Rosenthal r, as applicable based on the distribution.16,17 We classified the effect size as follows: very small (<0.2); small (0.2−0.5); moderate (0.5−0.8); large (0.8–1.3); very large (>1.3). For all the analyses, we considered a P value of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

ResultsCardiopulmonary resuscitation variablesCompressions (Cs)Table 1 shows the results for the chest compression variables. There was a lower percentage of compressions reaching the target depth with the 3:1 ratio (11%; IQR, 2−34) compared to the 15:2 ratio (26%; IQR, 13−53), with a P value of 0.005 and an effect size of 0.47. The median compression rate was higher in the 3:1 CPR tests (156 Cs/min; IQR, 151−161) compared to the 15:2 CPR tests (150 Cs/min; IQR, 149−153), with a P value of 0.001 and an effect size of 0.51. There were no statistically significant differences in the remaining compression variables.

Chest compression variables (n = 36).

| 15:2 ratio | 3:1 ratio | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Cs in correct depth range (%) | 26 | (13−53) | 11 | (2−34) | .005 (0.47)* |

| Cs with correct hand position (%) | 100 | (98−100) | 100 | (93−100) | .26 |

| Cs with complete recoil (%) | 100 | (91−100) | 97 | (92−100) | .42 |

| Average depth (mm)a | 35 | (31−38) | 35 | (32−37) | .88 |

| Average rate (Cs/min) | 150 | (149−153) | 156 | (151−161) | .001 (0.51)* |

Abbreviations: C, compression; min, minute.

Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < 0.05). *Effect size (Rosenthal r).

Effect size classification: very small (<0.2); small (0.2−0.5); moderate (0.5−0.8); large (0.8–1.3); very large (>1.3).

Table 2 shows the results for the ventilation variables. The median tidal volume was higher with the 3:1 ratio (27 mL; IQR, 23−32) than with the 15:2 ratio (24 mL; IQR, 21−28), with a P value of 0.002 and an effect size of 0.51. The median ventilation rate was higher with the 3:1 ratio (32 Vs/min; IQR, 26−35) compared to the 15:2 ratio (15 Vs/min; IQR, 14−16) with a P value of less than 0.001 and an effect size 0.87. The median minute volume with the 3:1 ratio (809 mL/min; IQR, 736−927) was significantly higher compared to the 15:2 ratio (351 mL/min; IQR, 312−406) with a P value of less than 0.001 and an effect size of 0.87. There were no significant differences in the remaining ventilation variables.

Ventilation variables (n = 36).

| 15:2 ratio | 3:1 ratio | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Effective Vs (%) | 100 | (97−100) | 99 | (91−100) | .06 |

| Average tidal volume (mL) | 24 | (21−28) | 27 | (23−32) | .002 (0.51)* |

| Adequate tidal volume (%) | 74 | (56−88) | 64 | (48−82) | .14 |

| Insufficient tidal volume (%) | 5 | (2−13) | 5 | (1−10) | .13 |

| Excessive tidal volume (%) | 10 | (1−38) | 21 | (8−37) | .053 |

| Average rate (Vs/min) | 15 | (14−16) | 32 | (26−35) | < 0.001 (0.87)* |

| Average minute volume (mL) | 351 | (312−406) | 809 | (736−927) | < 0.001 (0.87)* |

Abbreviations: V, ventilation; min, minute.

Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < .05). *Effect size (Rosenthal r).

Effect size classification: very small (<0.2); small (0.2−0.5); moderate (0.5−0.8); large (0.8–1.3); very large (>1.3).

Table 3 shows the results for the CPR quality variables. On average, fewer total ventilations were delivered with the 15:2 ratio (median, 60 ventilations; IQR, 55−63) compared to the 3:1 ratio (132 ventilations; IQR, 111−144) with a P value of less than 0.001 and an effect size of 3.97. There were no significant differences in the median duration of ventilations per cycle.

Overall CPR quality variables (n = 36).

| 15:2 ratio | 3:1 ratio | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Overall CPR quality variables | |||||

| Total number of compressions | 421 | (383−447) | 402 | (325−435) | .001 (0.69)* |

| Total number of ventilationsa | 60 | (55−63) | 132 | (111−144) | .001 (3.97)** |

| Mean duration of ventilations (s) | 2 | (2−3) | 2 | (1−3) | .57 |

Abbreviation: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < .05). *Effect size (Rosenthal r).

Effect size classification: very small (<0.2); small (0.2−0.5); moderate (0.5–0.8); large (0.8–1.3); very large (>1.3).

Fifty-six percent of participants felt that the 15:2 ratio would be a more comfortable strategy for CPR and considered that this ratio allowed them to deliver higher-quality ventilations. Likewise, 53% considered that the 15:2 ratio allowed them to perform high-quality chest compressions.

DiscussionInternational guidelines have established a compression-to-ventilation ratio of 3:1 for neonatal resuscitation in the delivery room.4,5,10 This recommendation is based on expert opinion and consensus. To date, no clinical trials have been conducted to demonstrate its effectiveness compared to other compression-to-ventilation ratios,4,5 such as the standard ratio that applies to all children outside the delivery room (15:2).

The main finding of our study, conducted in a simulated and controlled environment, was that the overall quality achieved with the 15:2 ratio was not inferior to that of the 3:1 ratio. With regard to individual quality variables, our data suggest that the 15:2 ratio is inferior to the 3:1 ratio in terms of the minute volume, but superior in terms of the potential improvement in chest compression quality. This may be beneficial in spite of the significantly lower minute volume values achieved with the 15:2 ratio (hypoventilation) compared to the 3:1 ratio, which achieves ventilation values in the target range. These results were consistent with those of other simulation studies that suggested that the 15:2 ratio may not be inferior to the standard (3:1) ratio.7 In addition, animal models suggest that different compression-to-ventilation ratios can achieve similar outcomes in terms of the return of spontaneous circulation, mortality, and hemodynamic recovery.6,18–20 In contrast, Hemway et al. noted that the 3:1 ratio was appropriate for newborn infants requiring resuscitation, without ruling out other options that may be valid.21

Ventilation is a crucial intervention in neonatal resuscitation,4 although high-quality chest compressions, when indicated due to bradycardia or asystole secondary to asphyxia, are essential to optimize coronary and cerebral perfusion to ensure recovery of the infant without neurologic sequelae.22 In real-world practice, the optimal compression-to-ventilation ratio to implement in neonatal CPR to optimize coronary and cerebral perfusion while providing adequate ventilation has yet to be established.6 From a theoretical standpoint, the 3:1 ratio may have drawbacks, 23 as it has been associated with hypercarbia and poor cerebral oxygen delivery.23 Our findings, as expected, suggest that the 3:1 ratio (in agreement with the findings reported by Hemway21) achieves higher values for different ventilation parameters compared to the 15:2 ratio. This is mainly because the 15:2 ratio achieves minute volume and respiratory rate values below the target range (hypoventilation) compared to the 3:1 technique, which achieves ventilation parameters within the theoretical normal range. Based on the ventilation data obtained in the simulations, the potential risk of volutrauma, pulmonary overdistension, and air leaks would be limited with both techniques. However, these results must be interpreted with caution, as real-world studies in actual neonatal patients have shown that it is not uncommon for even professional rescuers to hyperventilate infants during neonatal CPR,24,25 something that we did not observe in the current study in which CPR was performed in manikins. Similarly, animal studies have found excessive ventilation rates that caused significant increases in intrathoracic pressure, along with a notable reduction in coronary perfusion pressures and survival rates.24,26

Although the delivered minute volume was within the theoretical normal range (normal ventilation) with the 3:1 ratio and significantly lower with the 15:2 ratio (hypoventilation), we do not know what impact this may have on actual patients, as the optimal minute volume for neonatal resuscitation has not been clearly established and the clinical relevance of this difference is uncertain. Furthermore, in the case of cardiac arrest, effective chest compressions are essential for the recovery of spontaneous circulation,22 and it would be difficult to predict the impact of the reduced minute volume on the overall effectiveness of CPR with the 15:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio.

Based on our findings, switching to the standard ratio could simplify training and possibly have clinical relevance on account of the potential improvement in chest compression quality and decreased risk of manual ventilation-induced injuries during CPR, which is a solid foundation to support the performance of real-world studies and investigating the impact of the alternative ratio on immediate recovery and long-term outcomes.

Since most cases of cardiac arrest in the delivery room are secondary to asphyxia,4 it is a given that delivery of high-quality ventilations are of the essence. Still, once asphyxia is severe or prolonged enough to give rise to bradycardia or asystole, the return of spontaneous circulation is crucial and this requires immediate initiation of chest compressions with optimal technique in terms of hand positioning, rate, depth, recoil and minimal interruption.7 Healthy and vigorous infants have a heart rate of 120 to 160 beats per minute and a respiratory rate of 40 to 60 breaths per minute at birth.28 It has been estimated that a 3:1 ratio would allow delivery of 90 compressions and 30 ventilations per minute, but in our study, trainees achieved compression rates of 150 compressions per minute or greater with both ratios. In this regard, Bruckner et al. found that a maximum rate of 150 to 180 compressions per minute during CPR resulted in the highest cardiac output and arterial blood pressure.29 This is consistent with our findings, as the compression rate was in that optimal rate with both the 15:2 and 3:1 ratios.

Slightly more than half of the nursing students in our study considered the 15:2 ratio to be the most appropriate ratio for performing CPR, a subjective assessment that should be interpreted with caution. In contrast, in a study conducted by Li et al., health care professionals preferred the 3:1 CPR ratio,27 which could be explained by their previous training in CPR. Health care professionals have usually been specifically trained on neonatal resuscitation, in which the 3:1 ratio is the recommended standard.4,5,10 However, nursing students tend to be more familiar with the 15:2 ratio, which is widely used in pediatric CPR.

Implications for clinical practiceWe ought to note that many births around the world occur without assistance from skilled attendants,2,3 especially in settings where ongoing training and exposure to multiple protocols may be limited. This jeopardizes the reduction in neonatal mortality that is one of the key targets in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals.30 In situations where births are attended by less experienced personnel or those with limited access to well-rounded training, a uniform standardized approach to CPR with the 15:2 ratio, the one most commonly used in pediatric CPR, could facilitate both skill learning and retention as well as their application from childbirth. Although the material resources for performing CPR are the same for both ratios, the cognitive simplification of the algorithms could have a positive impact on the attitudes of rescuers and their effectiveness. Midwife training initiatives in Africa are an example of how this challenge can be effectively addressed by standardizing and simplifying training of health workers.31

LimitationsThere are several limitations to this neonatal CPR simulation study. First, since the study was based on simulation and not real-life practice, its results may not be fully extrapolated to real-world clinical scenarios. In addition, the study sample consisted of trained nursing students, who may not reflect the outcomes that would be achieved in a sample of medical providers (medical residents or attending physicians) with more experience in neonatal resuscitation. Ventilation, in particular, is a challenging maneuver in neonatal CPR, and differences in the profile of the rescuers could affect the performance and quality of the maneuvers. It should also be noted that the manikin model used in the study does not accurately replicate the pulmonary anatomy or mechanics of a real newborn, which could have affected the results that concern ventilation and hyperventilation. On the other hand, although we included data regarding the preferences of the participants, these only reflect the subjective perception of the trainees regarding the experience, as opposed to objective CPR quality metrics, and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Given these limitations, additional studies conducted in real-world settings with participants with varying qualifications and levels of experience (including physicians) are needed to validate the results obtained in this simulation study.

ConclusionsIn a simulated model of neonatal resuscitation, CPR with a 15:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio performed by nursing students achieved overall quality metrics comparable to CPR with a 3:1 ratio. While the 15:2 ratio was inferior compared to the standard 3:1 ratio in terms of ventilation, it was superior in terms of the quality of chest compressions. The implementation of a single, standardized compression-to-ventilation ratio for delivery of CPR from birth and throughout childhood (15:2) could simplify large-scale rescuer training and contribute to improve the effectiveness of neonatal resuscitation, especially in settings with limited resources for training on childbirth attendance. Our findings in a simulated environment support the performance of studies in real-world patients.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.