Methotrexate (MTX) is the drug of choice for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Its clinical efficacy is limited due to the development of adverse effects (AEs).

Patients and methodsA retrospective observational study was conducted on the AEs associated with MTX therapy in children diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis followed-up in a tertiary hospital between 2008 and 2016.

ResultsThe study included a total of 107 patients, of whom 71 (66.3%) were girls (66.3%). The median age at diagnosis was 6.4 years (IQR 3.1–12.4), with a median follow-up of 45.7 months (IQR 28.8–92.4). There were 48 patients (44.9%) with oligo arthritis, and 26 children (24.3%) with rheumatoid-factor negative polyarthritis. Of these, 52/107 (48.6%) developed AEs, with the most frequent being gastrointestinal symptoms (35.6%) and behavioural problems (35.6%). An age older than 6 years at the beginning of therapy increased the risk of developing AEs, both in the univariate (OR = 3.5; 95% CI: 1.5–7.3) and multivariate (12% increase per year) analyses. The doses used, administration route, or clinical form according to International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) clasiification, were not associated with the development of AEs. Twenty children required a dosage or route of administration modification, which resolved the AE in 11 (55%) cases. MTX was interrupted due to the development of AEs in 37/107patients (34.6%), mainly due to increased plasma transaminases (n = 14, 37.8%), gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 9, 24.3%) and behavioural problems (n = 6, 16.3%).

ConclusionsMTX is the therapy of choice for patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but50% of the children develop some form of AE. Although the AEs are not severe, they lead to interruption of therapy in 35% of the children.

El metotrexato (MTX) es el fármaco sistémico más utilizado en el tratamiento de pacientes con artritis idiopática juvenil. Su efectividad viene limitada por el desarrollo deefectos adversos (EA).

Pacientes y métodosEstudio observacional descriptivo retrospectivo de la frecuencia y tipo de EA asociados a MTX en pacientes con artritis idiopática juvenil seguidos en un hospital terciario en el periodo 2008-2016.

ResultadosSe estudió a 107 pacientes, 71/107 mujeres (66.3%) con edad al diagnóstico de 6,4 años (RIC 3,1-12,4) durante una mediana de seguimiento de 45,7 meses (RIC 28,8-92,4). El 44.9% (48 pacientes) tenía oligoartritis y el 24.3% (n = 26) poliartritis factor-reumatoide negativo. El 48.6% (52/107) desarrolló EA, siendo los más frecuentes los síntomas gastrointestinales y los trastornos conductuales (35.6% cada uno). La edad mayor de 6 años al inicio del tratamiento aumentaba el riesgo de desarrollar EA, tanto en el estudio univariable (OR = 3,5; IC95% 1,5-7,3) como en el multivariable (aumento del riesgo del 12% por año). La dosis, vía de administración o forma clínica según la clasificación de la Liga Internacional de Asociaciones de Reumatología (ILAR) no presentaban relación con el desarrollo de EA. Veinte niños precisaron cambio de dosis o vía de administración, resolviéndose el EA en 11 (55%). MTX se suspendió en 37/107 pacientes (34.6%) por EA, principalmente por hipertransaminasemia (n = 14; 37.8%), síntomas gastrointestinales (n = 9; 24.3%) y trastornos conductuales (n = 6; 16.3%).

ConclusionesMTX es el tratamiento de elección de niños con artritis idiopática juvenil pero produce EA en prácticamente el 50% de los pacientes. Aunque estos EA no son graves, obligan a interrumpir el tratamiento en el 35%.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) has a prevalence of 40–150 cases per 100 000 children and is the most frequent chronic rheumatic disease in the paediatric population. It is a heterogeneous disorder and comprehends 7 clinical forms1 based on the classification of the International League Against Rheumatism (ILAR). This classification is based on the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the disease. When the predominant symptom is peripheral arthritis, it is classified based on the number of involved joints as either oligoarticular (up to 4) or polyarticular (5 or more); the latter is further classified as rheumatoid factor (RF) positive or negative. The fourth category, the systemic form, is determined by the presence of systemic manifestations (fever, erythematous rash, serositis, generalised lymph node enlargement or organ enlargement), independently of the number of affected joints. Enthesitis-related arthritis is characterised by axial skeleton involvement and/or inflammation of the entheses. The sixth form is psoriatic arthritis, and the seventh, termed undifferentiated arthritis, includes all presentations that do not fulfil the criteria for any of the previous categories. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis can cause long-term disability.2

Methotrexate (MTX) is the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) of choice for most clinically significant forms of JIA3,4 and has a good safety profile.5 As monotherapy it achieves remission of the disease in 60%–70% of patients, while the combination of MTX with biologic DMARDs decreases the risk of antidrug antibody production.3,6

The most frequent adverse reactions (ARs) to MTX are not severe, although they may have an impact on adherence to treatment7 and its discontinuation.

The aim of our study was to determine the frequency and type of ARs to MTX in patients with JIA, the risk factors associated with their development and how the ARs were managed.

Sample and methodsWe conducted a retrospective, observational and descriptive cohort study that included all patients aged 0–16 years with a diagnosis of JIA managed at the Paediatric Rheumatology clinic of a tertiary care hospital and treated with MTX between 2008 and 2016.

We collected clinical and laboratory data from the electronic health record database of the hospital, including sex, age at diagnosis, clinical form of JIA based on the ILAR classification1 and presence or absence of ARs. All patients received a 5 mg dose of folic acid a week.

We classified ARs as gastrointestinal (abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, anorexia), hepatic (hypertransaminasaemia), cutaneous/mucosal (aphthous mouth ulcers, alopecia), haematologic (cytopenia), behavioural (anticipatory behaviour with development of abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms or significant anxiety before administration of the drug), infectious and other.

Given the frequency and nonspecificity of gastrointestinal symptoms, we only included gastrointestinal events associated with the administration of MTX that were not transient or whose frequency and/or intensity interfered with treatment.

We defined hypertransaminasaemia as elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) greater than twice superior the upper range of normal in the reference range applied in our hospital (45 IU/mL). A complete blood count (CBC) and liver function panel was performed in all patients 1 month after initiation of treatment and every 3–4 months thereafter. If the tests detected hypertransaminasaemia, we discontinued treatment and 1 month later repeated the liver function tests, reintroducing MTX if the transaminase levels had normalised or withdrawing treatment definitively if they remained elevated.

We collected the date, route of administration and dose of MTX at treatment initiation and at the time of detection of the AR, whether it was necessary to change the dose or route of administration of MTX due to the AR, and whether or not the AR resolved as a result. We also documented whether it was necessary to discontinue MTX, the reason for discontinuation and the drug chosen to replace it (biologic versus not biologic). Last of all, in patients in who MTX was reintroduced after resolution of the AR, we recorded the date of reintroduction, dose and route of administration and whether the AR recurred. For all patients, we collected the presence or absence of active arthritis or uveitis at the end of the study and the most recent C-reactive protein (CRP) level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) values in record. We defined remission based on the criteria for clinically inactive disease published by Wallace et al.8

We have summarised quantitative data using the mean or the median as measures of central tendency and the standard deviation (SD) or interquartile range (IQR) as measures of dispersion based on whether the distribution of the data was parametric or nonparametric, respectively. We summarised qualitative data as frequency distributions.

We assessed the association between categorical variables using the χ2 test and compared means or medians by means of the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate based on the shape of the distribution. We used logistic regression in the multivariate analysis. We defined statistical significance as a p-value of less than 0.05.

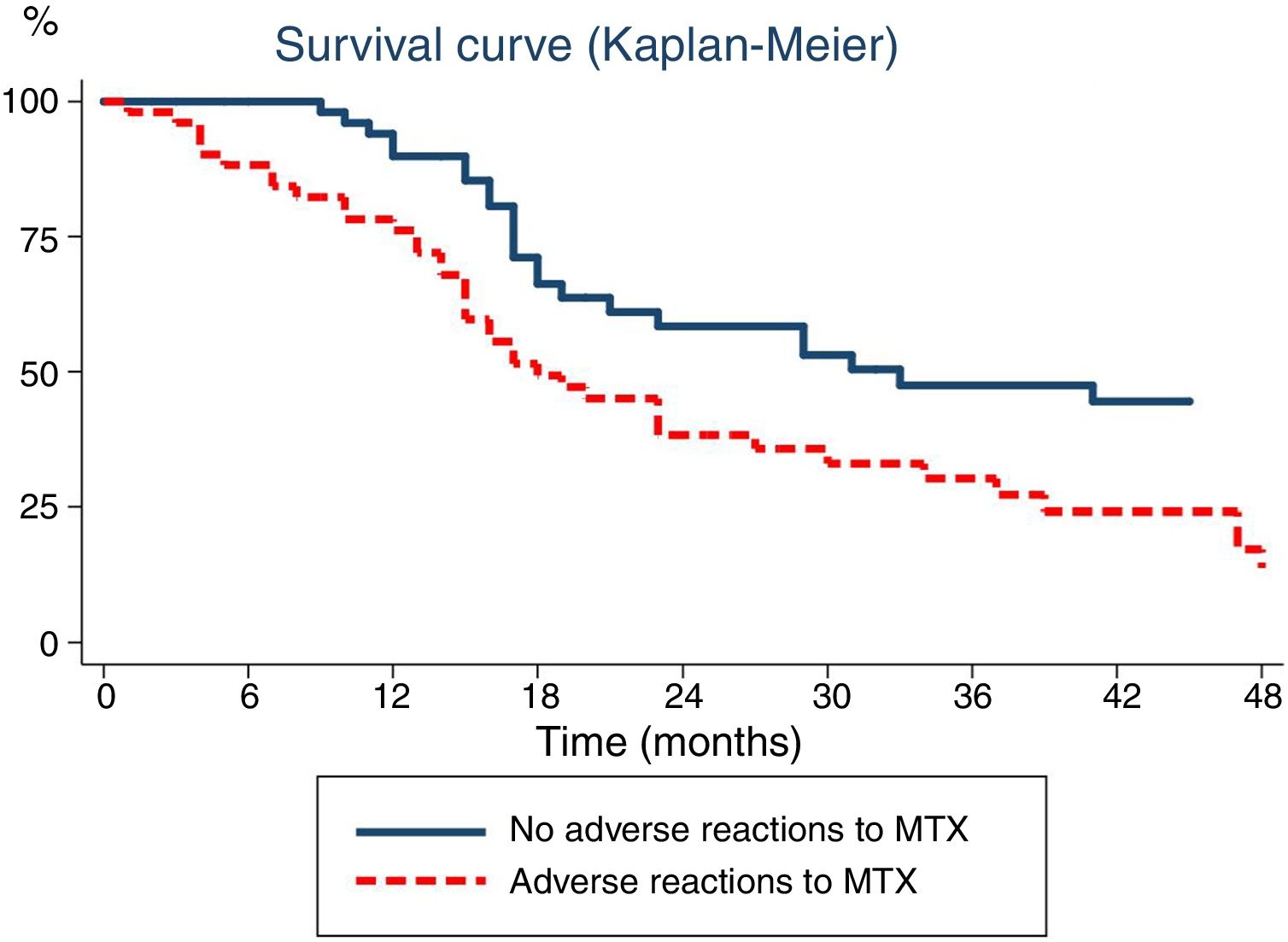

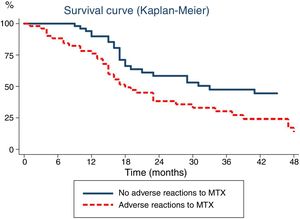

We investigated the temporal association between the use of MTX and the development of ARs by means of survival analysis with the Kaplan–Meier method, in which the discontinuation of MTX was the event of interest and the time-to-event was expressed in months.

The data were collected in a Microsoft Access 2003 (Redmond, Washington, USA) database and the statistical analysis performed with the software Stata version 4 (College Station, Texas, USA)

ResultsEpidemiological characteristics of the sampleThe study included 107 patients with JIA, of who 71 (66.3%) were female. The median age at diagnosis was 6.4 years (IQR, 3.1–12.4) and the median duration of followup was 45.7 months (IQR, 28.8–92.4).

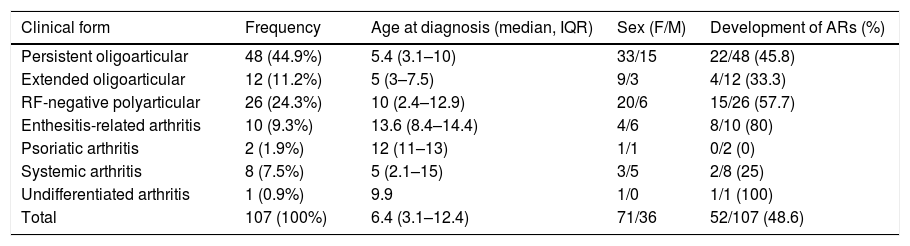

We classified patients based on the ILAR criteria1 (Table 1), and found that the most frequent clinical forms were persistent oligoarticular arthritis (n = 48; 44.9%) and RF-negative polyarticular arthritis (n = 26; 24.3%).

Demographic characteristics of the patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis included in the sample.

| Clinical form | Frequency | Age at diagnosis (median, IQR) | Sex (F/M) | Development of ARs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent oligoarticular | 48 (44.9%) | 5.4 (3.1–10) | 33/15 | 22/48 (45.8) |

| Extended oligoarticular | 12 (11.2%) | 5 (3–7.5) | 9/3 | 4/12 (33.3) |

| RF-negative polyarticular | 26 (24.3%) | 10 (2.4–12.9) | 20/6 | 15/26 (57.7) |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | 10 (9.3%) | 13.6 (8.4–14.4) | 4/6 | 8/10 (80) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2 (1.9%) | 12 (11–13) | 1/1 | 0/2 (0) |

| Systemic arthritis | 8 (7.5%) | 5 (2.1–15) | 3/5 | 2/8 (25) |

| Undifferentiated arthritis | 1 (0.9%) | 9.9 | 1/0 | 1/1 (100) |

| Total | 107 (100%) | 6.4 (3.1–12.4) | 71/36 | 52/107 (48.6) |

The mean dose of MTX was 15 mg/m2/week (SD, 2.3) and the median duration of treatment was 17.9 months (IQR, 12.8–36.6). When it came to the route of administration, 63 patients (59.4%) received MTX via subcutaneous injection. All patients received weekly folic acid supplementation.

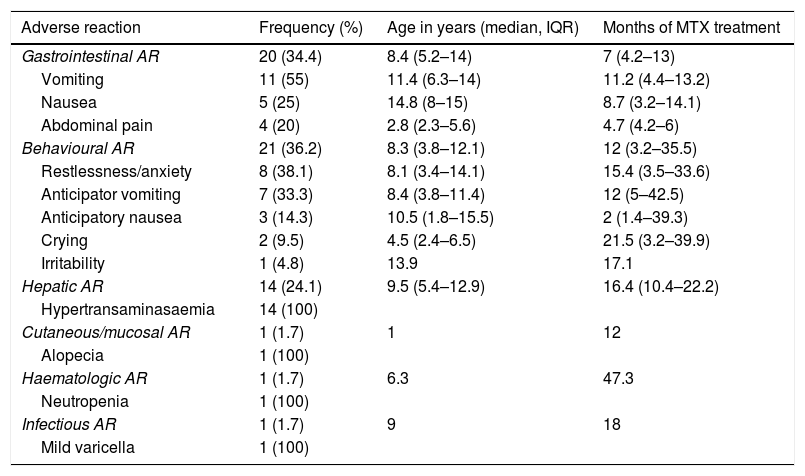

Frequency and type of adverse reactionsOf the 107 patients under study, 52 (48.6%) developed ARs (Table 2). Six (11.5%) developed more than 1 type of AR. The median duration of treatment to the development of ARs was 11.6 months (IQR, 4.3–17.9).

Type of adverse reactions documented in our sample, including their frequency, age at onset and duration of treatment with methotrexate at the time of the reaction.

| Adverse reaction | Frequency (%) | Age in years (median, IQR) | Months of MTX treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal AR | 20 (34.4) | 8.4 (5.2–14) | 7 (4.2–13) |

| Vomiting | 11 (55) | 11.4 (6.3–14) | 11.2 (4.4–13.2) |

| Nausea | 5 (25) | 14.8 (8–15) | 8.7 (3.2–14.1) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (20) | 2.8 (2.3–5.6) | 4.7 (4.2–6) |

| Behavioural AR | 21 (36.2) | 8.3 (3.8–12.1) | 12 (3.2–35.5) |

| Restlessness/anxiety | 8 (38.1) | 8.1 (3.4–14.1) | 15.4 (3.5–33.6) |

| Anticipator vomiting | 7 (33.3) | 8.4 (3.8–11.4) | 12 (5–42.5) |

| Anticipatory nausea | 3 (14.3) | 10.5 (1.8–15.5) | 2 (1.4–39.3) |

| Crying | 2 (9.5) | 4.5 (2.4–6.5) | 21.5 (3.2–39.9) |

| Irritability | 1 (4.8) | 13.9 | 17.1 |

| Hepatic AR | 14 (24.1) | 9.5 (5.4–12.9) | 16.4 (10.4–22.2) |

| Hypertransaminasaemia | 14 (100) | ||

| Cutaneous/mucosal AR | 1 (1.7) | 1 | 12 |

| Alopecia | 1 (100) | ||

| Haematologic AR | 1 (1.7) | 6.3 | 47.3 |

| Neutropenia | 1 (100) | ||

| Infectious AR | 1 (1.7) | 9 | 18 |

| Mild varicella | 1 (100) |

AR, adverse reaction; IQR, interquartile range.

The percentage given in each category is over the total of patients that developed an AR as opposed to the total sample. In addition, the percentage given for each specific adverse reaction (e.g. “vomiting”, “crying”) corresponds to the proportion of patients that experienced that reaction within the corresponding category (“gastrointestinal AR”) and not the total of patients.

The most frequent ARs were behavioural changes (n = 21; 19.6%) and gastrointestinal manifestations (n = 20; 18.7%). The third most frequent AR was hypertransaminasaemia (n = 14; 13%), with a mean ALT value of 212 IU/mL and a mean AST value of 143 IU/mL.

The least frequent types of AR, found in only 1 patient each, were cutaneous/mucosal (alopecia), hematologic (transient neutropenia) and infectious (uncomplicated varicella).

Risk factors associated with the development of adverse reactionsWhen we assessed the potential effect of demographic variables such as sex and age, we found that similar proportions of girls (50.7%) and boys (44.4%) developed ARs. However, the age at treatment initiation was greater in patients that developed some form of intolerance to MTX (median, 8.7 years; IQR, 5.2–13.6) compared to patients that did not (median, 4.9 years; IQR, 2.6–10.9), a difference that was statistically significant (P = .014). In the stratified analysis by age, we found that age greater than 6 years significantly increased the risk of developing ARs to treatment (OR = 3.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5–7.3).

The association of age and the development of ARs was not related to the duration of treatment. Patients aged less than 6 years received MTX for a longer time (median, 23.3 months; IQR, 16–41 months) compared to patients aged more than 6 years (median, 15.9 months; IQR, 10.4–25.4 months) (P = .01).

The analysis comparing the clinical forms of JIA did not evince differences in the frequency of ARs.

We also analysed variables related to treatment, including the dose of MTX and the route of administration. We did not find evidence of an association of dosage with the development of ARs, as the weekly dose used in patients that did not develop intolerance (15.8 mg/m2) was greater compared to those that developed ARs (13.9 mg/m2), a difference that was not statistically significant. We also found no differences based on the route of administration, as 44.2% of patients that received oral MTX developed ARs compared to 52.4% of those that received subcutaneous injections (P = .41).

We fitted several logistic regression models to assess the association between the development of ARs and the aforementioned variables (sex, age, clinical form of JIA based on ILAR classification, dose and route of administration of MTX). The best-fitting multivariate model was the one that included sex, despite this variable not making a statistically significant difference in the univariate analysis. Based on the multivariate analysis, the risk of having an AR increased by 12% with each year of age (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02–1.21); male sex was also associated with an increased risk, although this trend was not statistically significant (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.6–3.2).

Lastly, we analysed the association between the duration of MTX treatment and the development of ARs (Fig. 1). Survival analysis revealed that the probability of discontinuing treatment in patients that developed ARs increased with the duration of treatment: from 15% at 6 months to 24% at 12 months and 50% at 18 months.

Time elapsed from initiation of methotrexate (MTX) to its discontinuation, analysed with the Kaplan–Meier method. The continuous line represents the time elapsed to discontinuation of MTX due to inactive disease in patients that did not experience adverse reactions, while the dotted line corresponds to the time elapsed to discontinuation of MTX in patients that experienced adverse reactions.

Many patients developed ARs in association with MTX and required changes in treatment. Twenty children with inactive disease developed gastrointestinal intolerance or anticipatory behaviours. In 17 of these children (85%), the route of administration was changed from subcutaneous to oral, with resolution of the AR in 12 (70%). The other 3 patients (15%) were already receiving MTX via the oral route, so instead the dose was reduced, a measure that proved effective only in 1 case (33.3%). Therefore, changes in treatment achieved resolution of the AR in 13 children (65%), while MTX was discontinued in the remaining 7. During the subsequent followup, 2 of the 13 patients that responded to the switch to the oral route of administration developed another AR (hypertransaminasaemia), which led to the definitive discontinuation of MTX.

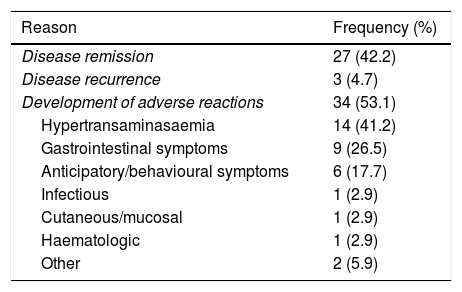

In 34/107 patients (31.8%), MTX was discontinued due to ARs (Table 3). This group included the 9 patients already mentioned and another 25 children. The 3 ARs that were the most frequent reasons for discontinuing MTX were hypertransaminasaemia (14/34; 41.2%), gastrointestinal manifestations (9/34; 26.5%) and behavioural changes (6/34; 17.7%).

Reasons for discontinuation of treatment with methotrexate.

| Reason | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Disease remission | 27 (42.2) |

| Disease recurrence | 3 (4.7) |

| Development of adverse reactions | 34 (53.1) |

| Hypertransaminasaemia | 14 (41.2) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 9 (26.5) |

| Anticipatory/behavioural symptoms | 6 (17.7) |

| Infectious | 1 (2.9) |

| Cutaneous/mucosal | 1 (2.9) |

| Haematologic | 1 (2.9) |

| Other | 2 (5.9) |

The percentage given in each category is over the total of patients in who treatment with methotrexate was discontinued, as opposed to the total of patients in the sample.

Four different strategies were used in the 34 patients that required discontinuation of MTX due to ARs depending on their clinical status. Patients that were in remission after a short duration of treatment (13/34; 38.2%) were given a non-biologic DMARD, which was leflunomide in every case. Patients that had exhibited a partial response to MTX prior to the development of the AR (9/34; 26.5%) were given a biologic drug. In 6/34 cases (17.6%), treatment was withdrawn entirely since the patient had been in remission for a long time, while in another 6/34 MTX was reintroduced once the AR had resolved.

In 3/107 patients (2.8%) MTX was discontinued due to recurrence of active disease and not due to development of ARs, and it was substituted by a biologic drug. A total of 12 patients received biologic drugs, 9 after developing ARs and 3 after experiencing a relapse. The biologic drug used most frequently, in the absence of ocular manifestations, was etanercept (83.3%); 2 children with uveitis received adalimumab.

In 27/107 (25.2%), MTX was discontinued due to disease remission.

Reintroduction of methotrexate following resolution of adverse reactions. OutcomesIn the period under study, MTX was reintroduced in 10 of the patients in who it had been discontinued (6/34 due to ARs and 4/27 due to disease remission). The mean dose given on reintroduction was 14.6 mg/m2/week (SD, 4.5 mg), similar to the previous dose, and in most cases the route of administration was the subcutaneous route (70%).

Half of the patients (5/10, 50%) tolerated reintroduction of MTX well and without complications, while the other 50% developed ARs that resulted in the definitive discontinuation of MTX.

Discontinuation of treatment and disease activityBy the end of the follow-up period, MTX had been discontinued in a total of 64 patients (59.8%) after a median duration of treatment of 21.6 months (IQR, 9.9–46.6). The reason for discontinuation of treatment was disease remission in 42.2% (27/64), disease recurrence in 4.7% (3/64) and ARs in the remaining 53.1% (34/64).

At the end of the study period, we assessed disease activity in patients treated with MTX as monotherapy. Sixty percent of the patients (65/107) met the criteria for remission proposed by Wallace. The rest did not meet these criteria, due to either the presence of disease activity (active arthritis in 15% and active uveitis in 7%), or persistent elevation of acute phase reactants (elevation of CRP in 19% and of ESR in 15%).

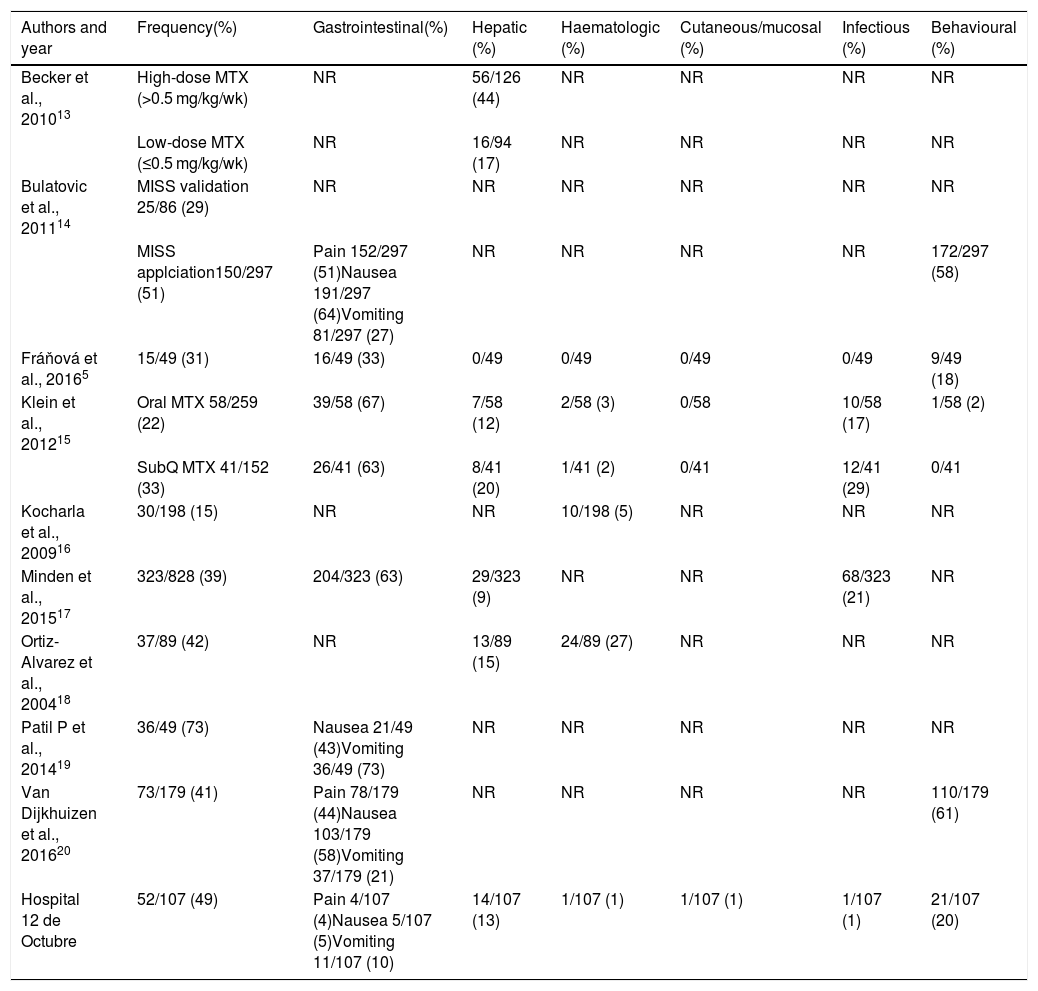

DiscussionOur study was the first analysis of the frequency and type of ARs associated with treatment with MTX in Spanish patients with a diagnosis of JIA. Since the efficacy of MTX for treatment of JIA was demonstrated in 1992,9 this drug has become the systemic drug of choice for the disease.10 Methotrexate has not only proven effective in decreasing the number of inflamed joints,11 but also in significantly improving health-related quality of life in these patients.12 In spite of this, few studies have addressed the ARs to MTX in patients with JIA5,13–21 (Table 4).

Frequency of the different types of adverse reactions associated with methotrexate treatment in patients with JIA.

| Authors and year | Frequency(%) | Gastrointestinal(%) | Hepatic (%) | Haematologic (%) | Cutaneous/mucosal (%) | Infectious (%) | Behavioural (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker et al., 201013 | High-dose MTX (>0.5 mg/kg/wk) | NR | 56/126 (44) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Low-dose MTX (≤0.5 mg/kg/wk) | NR | 16/94 (17) | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Bulatovic et al., 201114 | MISS validation 25/86 (29) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| MISS applciation150/297 (51) | Pain 152/297 (51)Nausea 191/297 (64)Vomiting 81/297 (27) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 172/297 (58) | |

| Fráňová et al., 20165 | 15/49 (31) | 16/49 (33) | 0/49 | 0/49 | 0/49 | 0/49 | 9/49 (18) |

| Klein et al., 201215 | Oral MTX 58/259 (22) | 39/58 (67) | 7/58 (12) | 2/58 (3) | 0/58 | 10/58 (17) | 1/58 (2) |

| SubQ MTX 41/152 (33) | 26/41 (63) | 8/41 (20) | 1/41 (2) | 0/41 | 12/41 (29) | 0/41 | |

| Kocharla et al., 200916 | 30/198 (15) | NR | NR | 10/198 (5) | NR | NR | NR |

| Minden et al., 201517 | 323/828 (39) | 204/323 (63) | 29/323 (9) | NR | NR | 68/323 (21) | NR |

| Ortiz-Alvarez et al., 200418 | 37/89 (42) | NR | 13/89 (15) | 24/89 (27) | NR | NR | NR |

| Patil P et al., 201419 | 36/49 (73) | Nausea 21/49 (43)Vomiting 36/49 (73) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Van Dijkhuizen et al., 201620 | 73/179 (41) | Pain 78/179 (44)Nausea 103/179 (58)Vomiting 37/179 (21) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 110/179 (61) |

| Hospital 12 de Octubre | 52/107 (49) | Pain 4/107 (4)Nausea 5/107 (5)Vomiting 11/107 (10) | 14/107 (13) | 1/107 (1) | 1/107 (1) | 1/107 (1) | 21/107 (20) |

JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MISS, Methotrexate Intolerance Severity Score; NR, not reported; subQ, subcutaneous.

The overall incidence of ARs observed in the Spanish patients in our sample was similar to that reported in other case series. Between one third and half of patients with JIA treated with MTX experience ARs.5,13–21 The types of ARs found in our study were also consistent with the previous literature, the most frequent being behavioural changes, followed by gastrointestinal manifestations and third of all hypertransaminasaemia. In our sample, gastrointestinal intolerance (abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting), developed by 20% of patients, was less frequent compared to other studies (21%–73%). These differences could be due to the methodology used, as we only considered ARs that were persistently associated with the administration of MTX or with a substantial frequency and/or intensity.

Other ARs, such as cytopenia, cutaneous or mucosal changes or infection, were much less frequent. Only 1% of the patients developed significant alopecia or neutropenia, and none had a severe infection. The cutaneous/mucosal and/or haematological complications of treatment are the best known, even though every study agrees on reporting a low frequency of these events.5,15,18 As for infection, 2 previous studies have reported a higher incidence15,17 compared to the one observed in our sample; both studies were based on German registers that categorised ARs based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (medDRA), so they included all infections, including mild cases. A study based on the claims data of the United States state-run Medicaid health programme established that the incidence of infections associated with MTX treatment in patients with JIA that require hospital admission is of 1.46 per 100 individuals per year.22

Different variables may be associated with the development of ARs, including age, sex, the clinical form of JIA, the dose and the route of administration of MTX, supplementation with folic acid and cultural factors. When it came to age, our results suggest that children aged more than 6 years at treatment initiation were more likely to develop intolerance compared to younger patients independently of the dose and duration of treatment with MTX, which was consistent with previous studies.5,21 Sex does not seem to contribute to the development of ARs, although 1 study found that hypertransaminasaemia was more frequent in female patients.13 The form of JIA also does not seem to play a relevant role with the exception of the higher frequency of abnormal blood test results in patients with systemic arthritis,16 which is probably attributable to the underlying disease. The role of the MTX dose is still a subject of debate in the literature. Fráňová et al.5 reported a proportion of intolerance similar to the one reported by other authors20 despite the use of 40% greater doses of MTX. We also found no association between the development of ARs and the dose used in our sample. Other authors, however, have reported a higher incidence of intolerance in patients receiving higher doses.13,21 The effect of the route of administration is also under debate. Factors such as the pain associated with subcutaneous injection do not seem to have a significant impact.23 Several authors have reported a higher frequency of intolerance with the parenteral administration of MTX,15,20,21 while others have found no differences,24 as was the case in our study, or have even found fewer ARs with the parenteral route compared to oral administration.25 In our study, we were unable to assess the impact of oral folic acid/folate supplementation because it was given to 100% of patients. Although some studies in the paediatric population have found an associated reduction in the incidence of ARs,26 others have not confirmed this finding.15,20 In any case, there is evidence from clinical practice and studies in adults that such supplementation may reduce the frequency of ARs associated with MTX, and consequently its use is recommended.3,4 Lastly, there is no question that cultural factors may have an impact on the tolerability of a chronic treatment. For instance, we ought to highlight the high frequency of behavioural changes found in studies conducted in the Netherlands, with an incidence as high as 60%,14,20 which is not observed in studies conducted in other countries, like ours in Spain, in which the incidence did not exceed 20%.5,15 A recent systematic review analysed potential predictors of the development of ARs, including several clinical, laboratory and genetic variables, and did not find any risk factors that could be applied to everyday clinical practice.27

Different strategies may be used once patients develop ARs, such as the addition of antiemetic drugs, behavioural therapy, changes in dosage or the route of administration and discontinuation of treatment. The usefulness of adding an antiemetic drug in case of nausea/vomiting, in particular ondansetron, was reviewed recently,28 and the evidence supporting its effectiveness was weak. Behavioural therapy has proven less effective than subcutaneous administration of MTX.29 None of these options was used in our hospital. The third alternative, which was changing the treatment, was used most frequently in our sample and in other studies,5,25 and achieved resolution of the AR in 65% of cases in our study. Decisions regarding the strategy to use should take into account the clinical condition of the patient (remission with treatment, nonresponse to MTX) and the severity or persistence (recurrence of hypertransaminasaemia) of the AR. Finally, ARs (most frequently hypertransaminasaemia and gastrointestinal manifestations) led to discontinuation of MTX in 35% of the sample.

In conclusion, MTX is a very useful drug in the management of JIA whose use is limited by the high frequency of associated ARs that, even if not severe, lead to its discontinuation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Barral Mena E, et al. Metotrexato en artritis idiopática juvenil: efectos adversos y factores asociados. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;92:124–131.