Medication reconciliation (MC) is one of the main strategies to reduce medication errors in care transitions. In Spain, several guidelines have been published with recommendations for the implementation and development of MC aimed at the adult population, although paediatric patients are not included. In 2018, a study was carried out that led to the subsequent publication of a document with criteria for selecting paediatric patients in whom CM should be prioritised.

ObjectivesTo describe the characteristics of paediatric patients most likely to suffer from errors of reconciliation (EC), to confirm whether the results of a previous study can be extrapolated.

MethodologyProspective, multicentre study of paediatric inpatients. We analysed the CE detected during the performance of the CM on admission. The best possible pharmacotherapeutic history of the patient was obtained using different sources of information and confirmed by an interview with the patient/caregiver.

Results1043 discrepancies were detected, 544 were identified as CD, affecting 317 patients (43%). Omission of a drug was the most common error (51%). The majority of CD were associated with drugs in groups A (31%), N (23%) and R (11%) of the ATC classification. Polymedication and onco-haematological based disease were the risk factors associated with the presence of CD with statistical significance.

ConclusionsThe findings of this study allow prioritisation of CM in a specific group of paediatric patients, favouring the efficiency of the process. Onco-haematological patients and polymedication are confirmed as the main risk factors for the appearance of CD in the paediatric population.

La conciliación de la medicación (CM) es una de las principales estrategias para disminuir los errores de medicación en las transiciones asistenciales. En España existen publicadas diferentes guías con recomendaciones para la implantación y desarrollo de la CM orientadas a población adulta, sin estar los pacientes pediátricos incluidos. En el año 2018 se llevó a cabo un estudio que permitió la posterior publicación de un documento con criterios de selección de pacientes pediátricos en los que priorizar la CM.

ObjetivosDescribir las características de los pacientes pediátricos con mayor probabilidad de sufrir errores de conciliación (EC), para confirmar si los resultados de un estudio previo son extrapolables.

MetodologíaEstudio prospectivo y multicéntrico con pacientes pediátricos ingresados. Se analizaron los EC detectados durante la realización de la CM al ingreso. La mejor historia farmacoterapéutica posible del paciente fue obtenida utilizando diferentes fuentes de información y confirmándose con una entrevista con el paciente/cuidador.

ResultadosSe detectaron 1.043 discrepancias, determinándose como EC 544, afectando a 317 pacientes (43%). La omisión de algún medicamento fue el error más común (51%). La mayoría de los EC se asociaron con los medicamentos de los grupos A (31%), N (23%) y R (11%) de la clasificación ATC. La polimedicación y la enfermedad de base onco-hematológica fueron los factores de riesgo asociados a la presencia de EC con significación estadística.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos de este estudio permiten priorizar la CM en un grupo concreto de pacientes pediátricos, favoreciendo la eficiencia del proceso. Los pacientes onco-hematológicos y la polimedicación se confirman como los principales factores de riesgo para la aparición de EC en población pediátrica.

Patient safety is a health care priority and a key aspect of health care quality. Pharmacological treatment is a complex process in which medication errors—understood as any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer—may occur. Medication errors have a considerable impact on patient morbidity and mortality, and a high proportion occur during care transitions. According to a technical report of the World Health Organization (WHO) published in 2017, Medication Safety in Transitions of Care,1 3%–97% of adult patients and 22%–72% of paediatric patients had at least one medication discrepancy at admission. In light of this situation, the WHO has proposed a new patient safety challenge to address three priority areas of medication, including transitions of care and high-risk situations involving particularly vulnerable patients, a group that encompasses paediatric patients,2 among whom the incidence of potential adverse drug events (ADEs) is 3 times greater compared to adult patients,3 and whose physiology has a lower capacity to buffer the effects of medication errors when they occur.

One of the main strategies proposed to reduce medication errors in transitions of care is medication reconciliation (MR), whose implementation and development is endorsed by many institutions and agencies at the national and international level, including the WHO,4 the Instituto para el Uso Seguro del Medicamento (ISMP),5 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),6 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO),7 the Ministry of Health of Spain8 or the Health Care Administration of the Community of Madrid.9

Medication reconciliation is defined as the formal and standardised process of obtaining an accurate and complete list of all drugs a patient is taking prior to any care transition, comparing it with the active prescription list, and analysing and resolving any identified discrepancies to guarantee that patients receive any medication required for chronic treatment as appropriate for their current condition in addition to any additional medication ordered following the care transition.10

In Spain, several guidelines have been published to assist in the implementation of MR, all of which make recommendations regarding the need to establish a standardised system for the recording and retrieval of patient medication and the use of software systems to facilitate the reconciliation process.11,12 However, all these guidelines have been developed for the adult population, and do not address specific issues concerning paediatric patients.

As is the case in the adult population, strategies need to be developed for the paediatric population to reach the greatest number of patients and improve efficiency in the use of health care resources. This requires the selection of patients who can benefit most. This selection can be based on specific characteristics of the patient or treatment with the potential to increase the probability of an error. In turn, this requires the identification of the factors associated to the occurrence of reconciliation errors (REs) in paediatric patients to establish the variables that would make it possible to select the patients at highest risk of a RE and serve as a tool to introduce MR in other paediatric care facilities.

In 2018, our research group carried out a project with the aim of introducing a MR programme at admission of paediatric patients, including patients with and without underlying disease and/or home medication, to be implemented by a hospital pharmacist.13 In the analysis of the data collected in this project, we identified variables (polypharmacy and/or neurologic and/or oncological/haematological underlying disease) that allowed the selection of the paediatric patients at highest risk of RE and, consequently, eligible for MR at admission to hospital.14 In doing so, we guaranteed MR in paediatric patients at highest risk of being subject to REs during care transitions, optimising the use of available resources. A study conducted by Iturgoyen Fuentes et al.14 was the first to yield criteria for the selection of patients to be prioritised in the implementation of MR in paediatric care facilities seeking to introduce this practice. It was an important milestone, given the scarcity of the literature on the subject of MR in the paediatric population and the lack of recommendations for paediatric patients in existing MR guidelines.

Since these criteria were established based on the experience of a single children’s hospital, the aim of our multicentre study was to include patients from other paediatric populations and with a broader range of underlying diseases compared to the Iturgoyen Fuentes et al. study to confirm whether the variables identified by the authors for the purpose of selecting patients at highest risk of REs are the same independently of the type of chronic disease, which is why the total number of patients included in the analyses of the multicentre study was smaller compared to the analysis conducted by Iturgoyen Fuentes et al.

Material and methodsProspective multicentre study of MR in the paediatric population conducted in 11 hospitals in Spain with the following inclusion criteria: paediatric patient with chronic disease and admission during the study period. Originally, the study period was going to span 11 months, but it was prolonged for an additional year on account of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We excluded patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric care, patients with an estimated length of stay of 24 h or less, patients for who we were unable to interview the parent or caregiver and patients in the emergency department.

We collected data on the following variables: date of admission, date of MR, age, sex, reason for admission, underlying disease, drug allergies or intolerances, number of drugs in home medication regimen (defining polypharmacy as 4 or more drugs15), narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, herbal or homeopathic medicine, updating of prescribed medication in the primary care prescription system, discrepancies, number of discrepancies per patient, type of discrepancy, pharmacy intervention (PhI), type of PhI, resolution of discrepancy, drug involved in the discrepancy and group of drugs involved in the discrepancy.

The drug groups involved in discrepancies were defined according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system of the WHO.

We documented the full name of each drug, its dose, drug allergies or intolerances, administration habits and adherence to treatment.

To obtain information concerning the selected patients and their pharmacological treatment, we searched hospital and primary care electronic health records, medical reports from other facilities and nursing medication administration records, and conducted a clinical interview with the patient/parent/guardian/caregiver to confirm the resulting findings.

Once we had obtained pharmacological treatment records for each patient selected for MR, we sought and analysed potential discrepancies between the medication records and the medication prescribed at admission in the context of the current clinical condition of the patient.

The classification of discrepancies was based on the definitions and classification proposed in the consensus document on MR of the Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria (Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy, 2009),11 classifying them as justified or unjustified, of which unjustified discrepancies were considered REs.

The last step involved the intervention by the pharmacy, consisting in the reporting the identified REs to the clinician in charge, either by documenting it in the electronic prescription system or, in the case of important PhIs, a direct verbal report.

In adherence to Organic Law 3/2018 on the protection of personal data and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 Regulation 2016/679 on the protection of confidential personal data, we assigned each patient a numerical code preceded by the initials of the participating centre.

The data were collected with the free software REDcap (Research Electronic Database Capture) y and analysed with the SAS statistical software suit, version 9.4.

We described quantitative variables with the mean and standard deviation in addition to other robust statistics, the median and interquartile range, and the minimum and maximum values. To assess factors associated with REs, we fitted a binomial logistic regression model in which the occurrence of REs was a dichotomous dependent variable and the independent variables were those found to be significantly associated with REs in the bivariate analysis. We used a stepwise approach to select the variables, reaching a final model that only included significant variables. We present the results of the analysis in terms of the odds ratio (OR) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). All tests were two-tailed and P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Drug Research Ethics Committee of the hospital that the principal investigator was affiliated to. We obtained informed consent from all the study participants.

ResultsSample and participating centresThe number of patients included in the study by each participating hospital can be found in Table 1.

Patients included by each participating hospital.

| Centro (Ciudad) | n |

|---|---|

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid) | 75 |

| Hospital San Joan de Deu (Barcelona) | 148 |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro (Madrid) | 16 |

| Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca (Murcia) | 45 |

| Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús (Madrid) | 68 |

| Complejo Hospitalario La Coruña (La Coruña) | 38 |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (Valencia) | 40 |

| Hospital Regional Universitario Carlos Haya (Malaga) | 70 |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona) | 80 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (Seville) | 87 |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (Gran Canaria) | 74 |

| Total | 741 |

In addition, Table 2 summarises the sociodemographic characteristics of the included patients.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients included in the study.

| Characteristic | (N = 741) |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 333 (44.9%) |

| Male | 408 (55.1%) |

| Median age ± SD (years) | 8.5 ± 5.5 (3.4−13.1) |

| IQR | |

| I | |

| Age group | |

| Newborn (0−29 days) | 0 |

| Infant (1 month–1 year) | 72 (9.7%) |

| Preschool-aged child (>1−5 years) | 219 (29.6%) |

| School-aged child (>5−12 years) | 248 (33.5%) |

| Adolescent(>12−18 years) | 202 (27.3%) |

| Median number of drugs in chronic medication regimen (IQR) | 4 (3−7) |

| Polypharmacy (≥4 drugs) | |

| Yes | 471 (63.6%) |

| No | 270 (36.4%) |

| Drug allergy/intolerance | |

| Yes | 41 (5.5%) |

| No | 700 (94.5%) |

| NTI drug | |

| Yes | 191 (25.8%) |

| No | 550 (74.2%) |

| Non-prescription, herbal or homeopathic medication | |

| Yes | 17 (2.3%) |

| No | 724 (97.7%) |

| Care setting | |

| Emergency care | 49 (6.6%) |

| Intensive care | 35 (4.7%) |

| Inpatient ward | 654 (88.3%) |

| Other | 3 (0.4%) |

IQR, interquartile range; NTI, narrow therapeutic index; SD, standard deviation.

Most of the 741 patients included in the study were admitted to the general paediatrics (28.2%), paediatric neurology (15.6%), haematology (11.5%) and oncology (10.3%) departments.

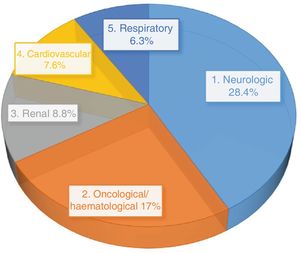

The most frequent type of underlying disease in the patients included in the study was neurologic disease (27.7%), followed by oncological/haematological disease (21.2%), renal disease (9.4%) and cardiovascular disease (8.4%).

Nearly 2/3 of the sample (63.3%) were treated with 4 or more drugs at home (polypharmacy), compared to 36.4% whose home medication ranged from 1 to 3 drugs.

In addition, the home medication of 199 patients (25.8%) included at least 1 narrow therapeutic index drug. The groups of drugs the patients were receiving most frequently were antiepileptic drugs (N03 subgroup, 49%), immunosuppressants (L04 subgroup, 37%) and thyroid therapy (H03 subgroup, 10%). The most frequently used active principles were valproic acid (34%), tacrolimus (26%) and levothyroxine (8.4%). It is important to take into account that some patients were taking more than 1 narrow therapeutic index drug concurrently.

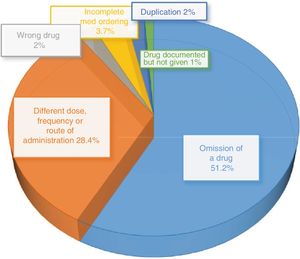

General findings of the analysis of reconciliation errorsDetected discrepanciesA total of 1043 discrepancies were detected. Of this total, 499 were justified based on the current condition of the patient, clear documentation of the change in the health records or confirmation by the physician that the change was intentional upon questioning by the pharmacist. The remaining 544 were confirmed to be REs (52% of the total discrepancies).

Patients with discrepanciesAt least 1 discrepancy was found in 494 patients, which corresponded to two thirds of the sample.

In half of the patients subject to discrepancies, there were 1–3 discrepancies. The maximum number of discrepancies found in a single patient was 9 (range, 1–9).

Patients with reconciliation errorsThe incidence of REs was 43% (at least 1 RE in 317 out of 741 patients). Table 3 summarises the characteristics of the patients subject to REs.

Characteristics of patients subject to at least 1 reconciliation error.

| Characteristic | (N = 317) |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 144 (45.4%) |

| Male | 173 (54.6%) |

| Median age (years) ± SD (range) | 8.4 ± 5.6 (0.1−26.8) |

| Age group | |

| Newborn (0−29 days) | 0 |

| Infant (1 month–1 year) | 37 (11.7%) |

| Preschool-aged child (>1−5 years) | 83 (26.2%) |

| School-aged child (>5−12 years) | 109 (34.4%) |

| Adolescent(>12−18 years) | 88 (27.8%) |

| Median number of drugs in chronic medication (range) (min-max) | 5 (1−18) |

| Polypharmacy (≥4 drugs) | |

| Yes | 223 (70.3%) |

| No | 94 (29.7%) |

| Drug allergy/intolerance | |

| Yes | 21 (6.6%) |

| No | 296 (93.4%) |

| NTI drug | |

| Yes | 81 (25.6%) |

| No | 236 (74.4%) |

| Non-prescription, herbal or homeopathic medication | |

| Yes | 7 (2.2%) |

| No | 310 (97.8%) |

| Care setting | |

| Emergency care | 21 (6.6%) |

| Intensive care | 9 (2.8%) |

| Inpatient ward | 286 (90.2%) |

| Other | 1 (0.3%) |

NTI, narrow therapeutic index; SD, standard deviation.

A majority of patients with at least 1 RE were admitted to the general paediatrics (30.1%), neurology (15%), haematology (9.1%), surgery (8.4%) or oncology (7.7%) wards.

Fig. 1 presents the distribution by type of disease of patients subject to REs.

Type of reconciliation errorsThe most frequent type of RE was omission of a drug, which amounted to 51.2% of the total REs, followed by the category of “differences in dose, frequency or route of administration”, which amounted to 28.4% of the total (Fig. 2).

Drugs involved in reconciliation errorsTable 1 presents the ATC groups of the drugs involved most frequently in REs. They were groups A (31%), N (23%), R (11%), B (7%), J (6%) and H (5%). When it came to specific subgroups, the ones involved most frequently were antiepileptics (N03, 12%), vitamins (A11, 12%) and drugs for obstructive airway diseases (R03, 8%).

Table 4 presents the ATC groups for the drugs involved most frequently in REs.

ATC groups involved in reconciliation errors.

| ATC group of drug involved in RE | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Group A | 168 | 31 |

| Group B | 37 | 7 |

| Group C | 28 | 5 |

| Group D | 5 | 1 |

| Group G | 8 | 1 |

| Group H | 27 | 5 |

| Group J | 35 | 6 |

| Group L | 19 | 3 |

| Group M | 9 | 2 |

| Group N | 124 | 23 |

| Group P | 2 | 0.5 |

| Group R | 62 | 11 |

| Group S | 8 | 1 |

| Group V | 3 | 0.5 |

| Diets | 9 | 1 |

ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system; RE, reconciliation error.

The most frequently involved drug subgroups/active principles were antiepileptic drugs (12.3%), vitamin D (8.6%), omeprazole (5.1%) and trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole (3.1%).

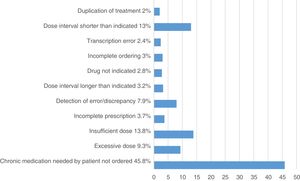

Analysis of pharmacy interventionsThere were a total of 493 PhIs, of which 433 were accepted (87.8%). Fig. 3 presents the most frequent reasons for pharmacy involvement.

The most frequent reasons for intervention were “failure to prescribe chronic and necessary treatment” (226 PhIs; 45.8% of total) and “insufficient dose” (68 PhIs; 13.8% of total), which were consistent with the two most frequent types of identified REs (omission, difference in dose).

Of the 493 PhIs that took place, 81 concerned patient safety (18.7%), 212 the effectiveness of treatment (49%) and 140 both safety and effectiveness (32.3%).

When we compared the demographic characteristics, underlying disease, home medication, number of drugs in home medication or inclusion of NTI drug(s) in the chronic medication regimen in the group of patients not subject to REs versus the group subject to REs, we did not find statistically significant differences between the groups in any variable except polypharmacy and the type of underlying disease (Table 5). We found polypharmacy in 58.5% of the group without REs compared to 70.3% of the group subject to REs. There was a statistically significant difference between patients with and without polypharmacy (OR = 0.59; P < 0.0009) and in patients with oncological/haematological underlying disease (OR = 1.59; P < 0.0172).

Assessment of the association between study variables and the probability of reconciliation errors.

| Characteristics | No reconciliation error (%) | Reconciliation error(s) (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 44.6 | 45.4 | >0.05 |

| Male | 55.4 | 54.6 | |

| Age group | |||

| Newborn (0−29 days) | 0 | >0.05 | |

| Infant (1 month–1 year) | 8.3 | 11.7 | |

| Preschool-aged child (>1−5 years) | 32.1 | 26.2 | |

| School-aged child (>5−12 years) | 32.8 | 34.4 | |

| Adolescent(>12−18 years) | 26.9 | 27.8 | |

| NTI drug | |||

| Yes | 25.9 | 25.6 | >0.05 |

| No | 74.1 | 74.4 | |

| Main underlying disease | |||

| Neurologic disease | 27.1 | 28.4 | >0.05 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 4.5 | 5 | |

| Renal disease | 9.9 | 8.8 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 | 7.6 | |

| Oncological/haematological | 24.3 | 17 | 0.0182 |

NTI, narrow therapeutic index; SD, standard deviation.

The development and implementation of standardised protocols to ensure the continuity of pharmacotherapy based on MR processes is essential to coordinate and intervene at every critical point in care transitions, which would have a significant clinical impact, in addition to the development of strategies for patient selection based on risk or of clinical practice guidelines for medication reconciliation.

In adult patients, patient age, polypharmacy, multimorbidity and the use of NTI drugs are well-established risk factors for REs.16–19 In consequence, recommendations, guidelines and patient selection algorithms have been developed to increase the efficiency of MR.

To our knowledge, this is the first multicentre study (11 hospitals) on MR at admission including paediatric patients with chronic disease.

The sample in our study was substantially larger compared to other recently published studies on MR in the paediatric age group.20,21

In our study, 43% of the patients were subject to at least 1 RE, compared to 13% in the study conducted by Abu Farha et al.,20 14% in the study by Santos Alcántara et al.21 and 22% in the study by Coffey et al.22 One of the possible explanations for this difference is the multicentre design of our study, which allowed a larger sample size and the inclusion of patients with a broader range of underlying diseases and treatments compared to patients managed in a single centre.

Furthermore, our study considered patients with polypharmacy, a criterion that was not applied in the studies by Abu Farha et al.20 (which included patients with chronic treatment with at least 1 drug), Santos Alcántara et al.21 (no restrictions to inclusion based on the number of drugs) or Coffey et al.22 The application of more restrictive inclusion criteria increases the probability of bias, as described in the studies by Stone et al.,23 which only included children with medically complex disease, or by Rousseau et al.,24 conducted in patients whose chronic treatment included a minimum of 4 drugs or high-risk drugs. As was the case in our sample, omission was the most frequently identified type of RE in most previous studies. In developing a protocol to standardise medication reconciliation in health care facilities, it would be advisable to include, for every patient, the review of potential omissions not justified by the current condition of the patient.

In our study, cholecalciferol and omeprazole were 2 of the active principles most frequently involved in REs, in agreement with the findings of Abu Farha et al.20 In the study by Santos Alcántara et al.,21 conducted in the paediatric ward of a hospital in Brazil, drugs in the J group were most frequently involved in the REs identified in 3 different care transitions (admission, transfers between wards and discharge). In our study, the J group was also one of the groups involved most frequently in REs. Within this group, one of the most frequently involved active principles was trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole, which was frequently used in inappropriate doses or schedules for prophylaxis in oncological patients or carriers of long-term indwelling urinary catheters.

When we analysed the risk factors associated with an increased risk of a RE, we only found a significant association with oncological/haematological underlying disease and polypharmacy. In the study by Iturgoyen Fuentes et al. conducted in a single children’s hospital,14 some of the identified predictors coincided with those identified in adult patients; for instance, school-aged children and adolescents were at increased risk of REs compared to other age groups, such as preschool-aged children (age). In addition, patients with neurologic or oncological/haematological underlying disease and patients whose chronic medication included NTI drugs were also at increased risk of REs compared to children with other types of underlying disease or whose chronic medication did not include any NTI drugs. The findings of the study conducted by Iturgoyen Fuentes et al.14 motivated us to design a multicentre study to confirmed its conclusions in a larger sample including patients with a broader range of underlying diseases. We were able to confirm that both polypharmacy and the presence of oncological/haematological disease were associated with an increased risk of medication reconciliation error.

When it came to polypharmacy, our findings were consistent with those of many studies in adult patients16–19 as well as studies in the paediatric population, such as those by Coffey et al.22 or Nolt et al.25

The study by Condren et al.26 found that the difference in the number of discrepancies between paediatric patients with medically complex chronic disease and those with non-complex disease was statistically significant, with a mean of 5.63 versus 3.77 discrepancies per patient (P = 0.005). Their findings were similar to those of our study, in which underlying oncological/haematological disease, generally considered complex and chronic disease and associated with complex pharmacological treatment, was identified as a factor associated with REs.

At the same time, the paediatric study of Condren et al.26 also determined that the number of drugs was a stronger predictor of discrepancies in reconciliation than disease complexity, which can allow the allocation of resources based on the complexity of pharmacological treatment as opposed to universal intervention in all patients with chronic disease. Thus, the number of drugs or the level of polypharmacy is probably a more precise approach for the stratification and identification of patients who could benefit most from MR.

ConclusionMedication reconciliation should be a considered a priority in children’s hospitals. At the international level, hospital accreditation by the Joint Commission International includes MR among the required safety standards, which is reflected in a decreased frequency of REs during transitions of care.20 The findings of our study support that polypharmacy and/or oncological/haematological disease are the main variables to consider in the prioritisation of patients eligible for medication reconciliation. Thus, the analysis of a sample that was more heterogeneous compared to the one in the study by Iturgoyen Fuentes et al.14 suggested that neurologic disease did not have as great an impact on the incidence of REs as previously described.

FundingThe study was funded by the Fundación Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria through the 2019–2020 grant programme.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Manrique Rodriguez S, Martinez Fernandez-Llamazares C, Taladriz Sender I (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid).

Salazar Valdebenito C, Arrojo Suarez J, Font Barceló A, Villaronga Flaque M (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona).

Rodriguez Marrodán B, Alcaraz Lopez JA, Lozano Llano C (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, Madrid).

Garrido Corro B, Jose Blazquez Alvarez MJ (Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia)

Gonzalez Andres D, Agüi Callejas AM, García López I (Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid)

Martinez Roca C, Fernandez Oliveira C (Complejo Hospitalario La Coruña)

Garcia Robles AA, Ferrada Gasco A (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia)

Gallego Fernandez C, Fernandez Cuerva C, Fernandez Martin JM, Pintado Alvarez A, Yunquera Romer L, Alcaraz Sanchez JJ (Hospital Regional Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga)

Pau Parra A, Jimenez Lozano I, Garcia Palop B, Cabañas Poy MJ, Parramón Teixido CJ (Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona)

Moleon Ruiz M, Araujo Rodriguez FJ, Mejías Trueba M, Tristancho Pérez A, Alvarez del Vayo Benito C, Fernandez Rubio B, Rodríguez Ramallo H, Báez Gutiérrez N (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla)

Cristina Otero Villalustre, Hernández Gago Y, Diego Dorta Vera D, Fernandez Vera D, Inés Ruiz Santos I (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular, Gran Canaria)