Specialized paediatric and neonatal transport is a useful and essential resource in the interhospital transfer of these patients. It allows bringing the material and personal resources of an intensive care unit closer to the regional hospitals where the patient can be found. The benefits of these teams are very well demonstrated in the literature. These units should be part of the emergency systems, while it would be recommended that they be staff integrated in the tertiary hospitals, in order to maintain the necessary skills and competencies. The team, made up of physicians, nurses and emergency medical technicians, must master both the pathophysiology of transport and that of the critical patient in this age range. A high quality of both human and care is important, so continuous training and periodic recycling will be essential to be compliant with the quality indicators in transport. Likewise, it is essential to have specific vehicles adapted to this function, which allow carrying the wide variety of necessary material, as well as the electromedicine that is required. However, in Spain this paediatric and neonatal transport model is not standardized and therefore is not homogeneous: there are different models that do not always provide adequate quality, making it necessary to implement specialized units throughout the country to guarantee sanitary transport quality to any critical child or neonate.

El transporte pediátrico y neonatal especializado es un recurso útil y esencial en el traslado interhospitalario de estos pacientes. Permite acercar los recursos materiales y personales de una unidad de cuidados intensivos a los hospitales comarcales donde se pueda encontrar el paciente. Los beneficios de estos equipos están muy bien demostrados en la literatura. Estas unidades deberían formar parte de los sistemas de emergencias, al mismo tiempo que sería recomendable que fueran personal integrado en los hospitales terciarios, con el fin de mantener las habilidades y competencias necesarias. El equipo, compuesto por médicos, enfermeros y técnicos de emergencias sanitarias tiene que dominar tanto la fisiopatología del transporte como la del paciente crítico en este rango de edad. Es importante una alta calidad tanto humana como asistencial, por lo que la formación continuada y el reciclaje periódico serán imprescindibles para poder cumplir correctamente con los indicadores de calidad en transporte. Así mismo, es fundamental contar con vehículos propios y adaptados a su función, que permitan llevar la gran variedad de material necesario, así como la electromedicina que se requiere. Sin embargo, en España este modelo de transporte pediátrico y neonatal no está estandarizado y por lo tanto no es homogéneo: existen diferentes modelos que no siempre aportan una adecuada calidad, siendo necesario la implantación de unidades especializadas en todo el país para garantizar un transporte sanitario de calidad a cualquier niño o neonato crítico.

The transport of critically ill children continues to be an area to improve in Spanish emergency medical services (EMS) systems. At present, the human and material resources allocated to this process are inadequate to address the specific needs of children, and transports are frequently performed under significantly lacking conditions. This has motivated 4 scientific societies in Spain, the Sociedad Española de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos (Spanish Society of Paediatric Intensive Care, SECIP), Sociedad Española de Neonatología (Spanish Society of Neonatology, SENeo), Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Care, SEUP) and the Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias (Spanish Society of Emergency and Urgent Care, SEMES) to start collaborating in pursuit of a shared goal: the optimization of paediatric and neonatal transport (PNT) in Spain in every age range. The first step in this collaboration took place a few months ago with the publication of a position statement regarding the need to create PNT units for interhospital transport (IHT).1

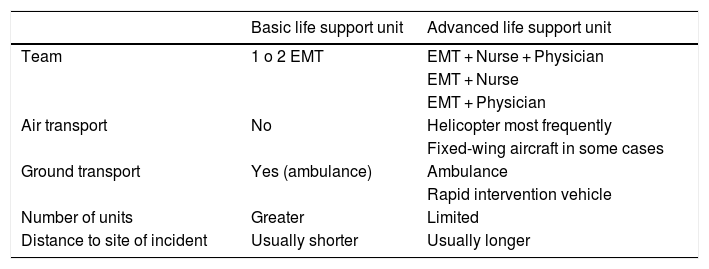

In Spain, paediatric primary transport (generally from transfer of patients from site of illness or injury to the nearest hospital) is usually carried out by the EMS system of each autonomous community in Spain and coordinated through a switchboard. The units that provide this initial care and transport are basic or advanced life support units (Table 1) that also transport critically ill adults. At present, there are no standardised requirements regarding equipment or the training in paediatrics of the staff in these units.

Characteristics of life support units of emergency medical services systems in Spain.

| Basic life support unit | Advanced life support unit | |

|---|---|---|

| Team | 1 o 2 EMT | EMT + Nurse + Physician |

| EMT + Nurse | ||

| EMT + Physician | ||

| Air transport | No | Helicopter most frequently |

| Fixed-wing aircraft in some cases | ||

| Ground transport | Yes (ambulance) | Ambulance |

| Rapid intervention vehicle | ||

| Number of units | Greater | Limited |

| Distance to site of incident | Usually shorter | Usually longer |

EMT, emergency medical technician.

Secondary transport involves IHT, and in the specific case of critically ill children usually involves transport from the hospital where stabilization is initiated to another hospital with greater resources to manage the patient’s condition and, in some instances, transport back to the original hospital. It is during IHT that paediatric equipment should never be lacking, as this allows to initiate the care at the sending hospital (SH) that the children will be receiving in the receiving unit (most likely a paediatric intensive care unit [PICU] or neonatal intensive care unit [NICU]) with awareness and anticipation of the potential complications that could emerge during transport.2,3 The benefits of it are well documented in the literature,4–7 some short-term (decrease in morbidity, mortality and length of stay) and others long-term (cost-effectiveness in child health and reduction in health care costs).

Our aim was to review the advantages of using specialised PNT, provide an updated perspective on the situation of PNT in Spain and highlight the human and material resources required for this service.

Current situation of PNT in SpainAt the international level, no particular model of transport team has been established in terms of its composition,8,9 and multiple options apply: respiratory therapist and nurse, nurse and adjunct physician or nurse and resident physician, among others, in addition to 1 or 2 technicians. Spain has opted for a model consisting of an emergency medical technician (EMT), nurse and/or physician.

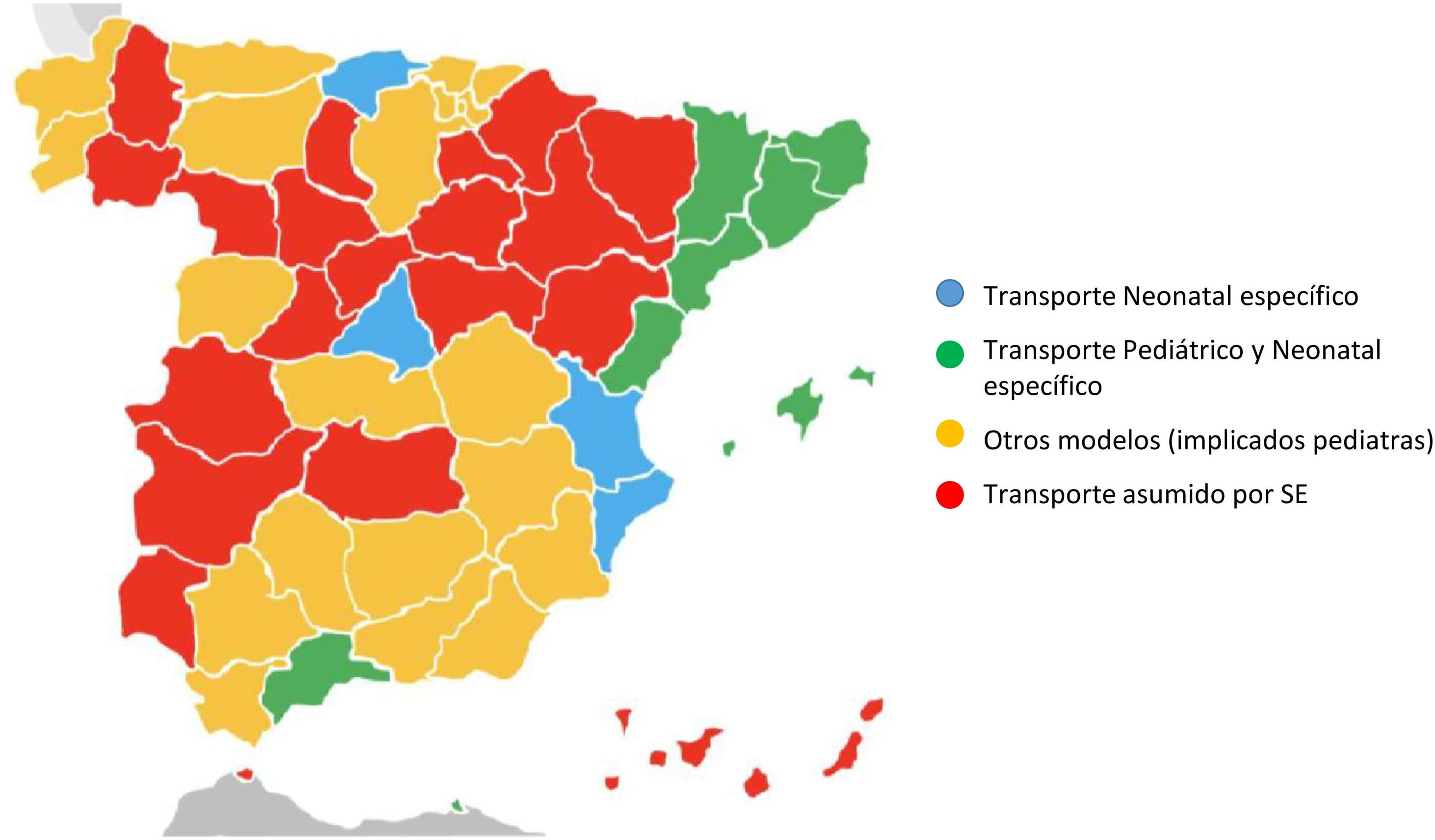

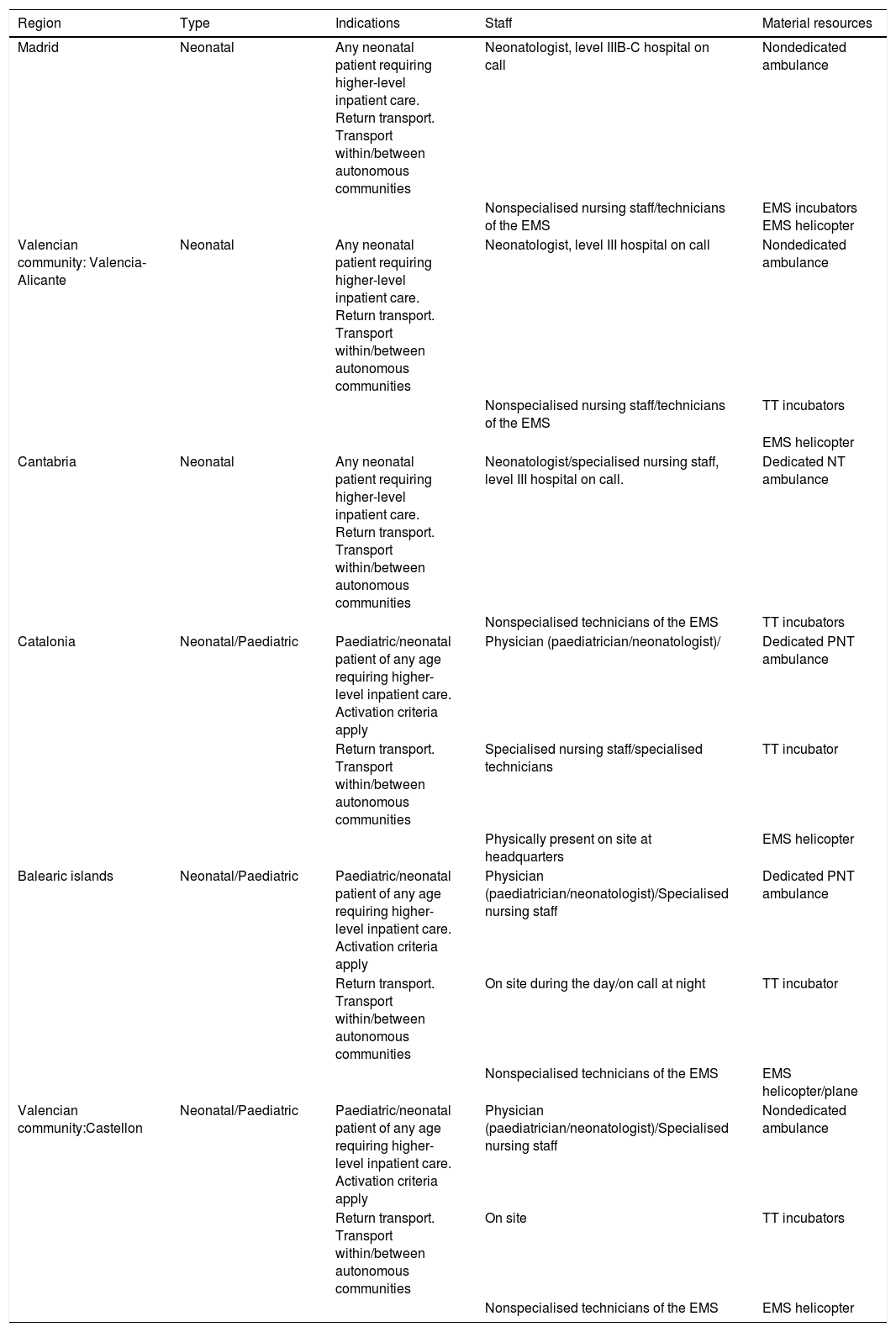

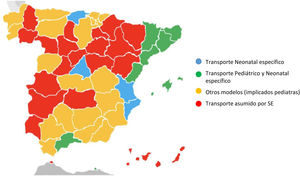

The composition is the same in PNT teams, with the added requisite that every member of the team (paediatrician/neonatologist, nurse and EMT) should have specific training in paediatric/neonatal care and medical transport, although this is not always the case in real-world practice. A variety of models can be found throughout Spain (SENeo 2018 nationwide survey) that differ in how transport is managed and in the composition of the transport team (Fig. 1, Tables 2A, 2B and 2C). This heterogeneity is partly explained by the characteristics of each autonomous community (economic, sociodemographic and geographical). However, since children have the right to receive the best possible care during medical transport, as established by articles 3 and 24 of the Declaration of the Rights of Children10 and articles 20 and 30 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978,11 we believe that the following is warranted:

- -

For all children of any age to be extended the right to this service.

- -

For staff in these teams to have extensive knowledge and skills in paediatric and neonatal critical care and experience and knowledge of medical transport.

- -

All medical devices and stabilization supplies should be available and ideally located in the vehicles of the specialised team.

Specialised PNT models in Spain.

| Region | Type | Indications | Staff | Material resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid | Neonatal | Any neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Return transport. Transport within/between autonomous communities | Neonatologist, level IIIB-C hospital on call | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Nonspecialised nursing staff/technicians of the EMS | EMS incubators EMS helicopter | |||

| Valencian community: Valencia-Alicante | Neonatal | Any neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Return transport. Transport within/between autonomous communities | Neonatologist, level III hospital on call | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Nonspecialised nursing staff/technicians of the EMS | TT incubators | |||

| EMS helicopter | ||||

| Cantabria | Neonatal | Any neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Return transport. Transport within/between autonomous communities | Neonatologist/specialised nursing staff, level III hospital on call. | Dedicated NT ambulance |

| Nonspecialised technicians of the EMS | TT incubators | |||

| Catalonia | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. Activation criteria apply | Physician (paediatrician/neonatologist)/ | Dedicated PNT ambulance |

| Return transport. Transport within/between autonomous communities | Specialised nursing staff/specialised technicians | TT incubator | ||

| Physically present on site at headquarters | EMS helicopter | |||

| Balearic islands | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. Activation criteria apply | Physician (paediatrician/neonatologist)/Specialised nursing staff | Dedicated PNT ambulance |

| Return transport. Transport within/between autonomous communities | On site during the day/on call at night | TT incubator | ||

| Nonspecialised technicians of the EMS | EMS helicopter/plane | |||

| Valencian community:Castellon | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. Activation criteria apply | Physician (paediatrician/neonatologist)/Specialised nursing staff | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Return transport. Transport within/between autonomous communities | On site | TT incubators | ||

| Nonspecialised technicians of the EMS | EMS helicopter |

EMS, emergency medical services; NT, neonatal transport; PNT, paediatric and neonatal transport; TT, transport team.

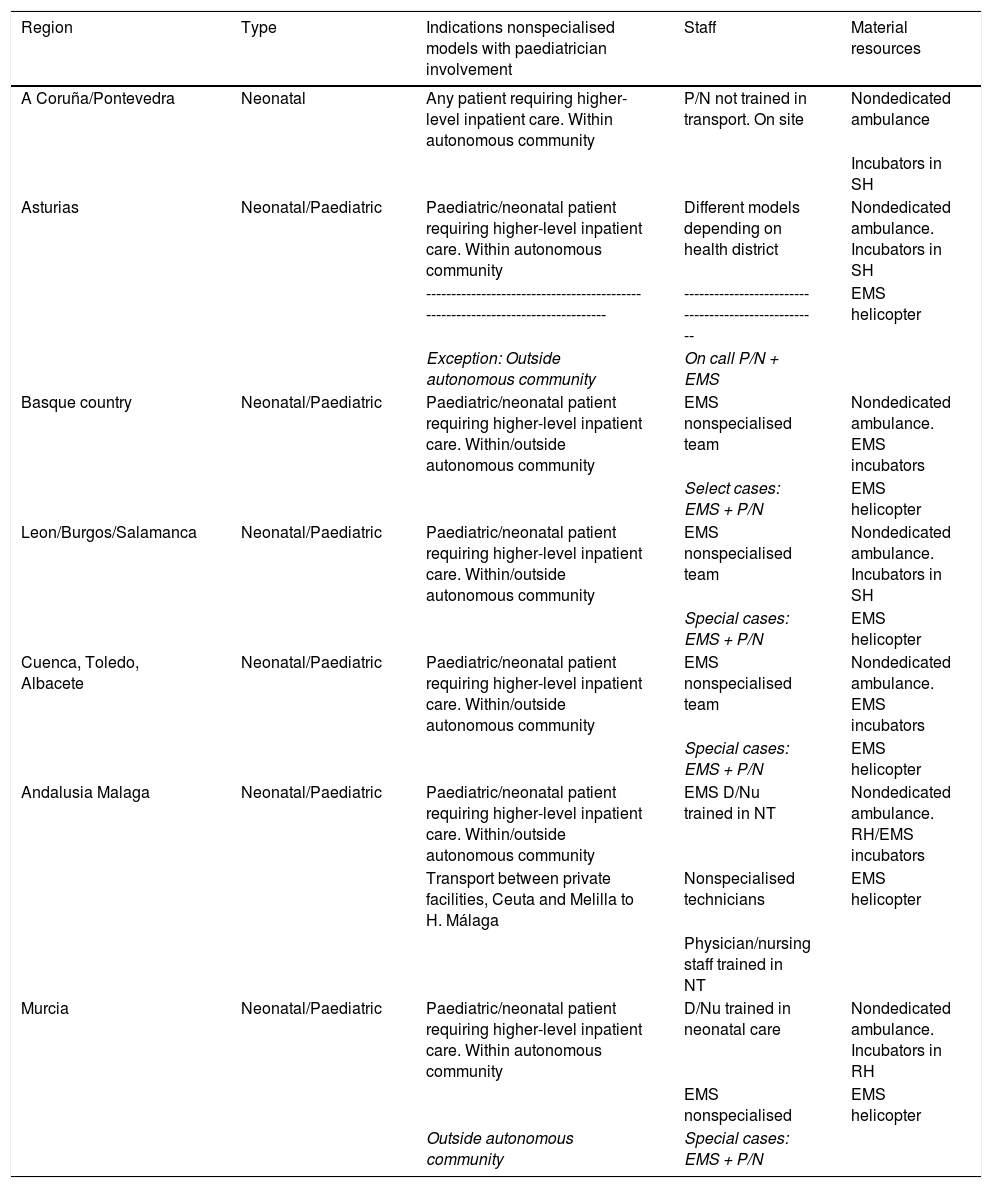

Nonspecialised PNT models in Spain that include paediatricians.

| Region | Type | Indications nonspecialised models with paediatrician involvement | Staff | Material resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Coruña/Pontevedra | Neonatal | Any patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within autonomous community | P/N not trained in transport. On site | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Incubators in SH | ||||

| Asturias | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within autonomous community | Different models depending on health district | Nondedicated ambulance. Incubators in SH |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------- | EMS helicopter | ||

| Exception: Outside autonomous community | On call P/N + EMS | |||

| Basque country | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within/outside autonomous community | EMS nonspecialised team | Nondedicated ambulance. EMS incubators |

| Select cases: EMS + P/N | EMS helicopter | |||

| Leon/Burgos/Salamanca | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within/outside autonomous community | EMS nonspecialised team | Nondedicated ambulance. Incubators in SH |

| Special cases: EMS + P/N | EMS helicopter | |||

| Cuenca, Toledo, Albacete | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within/outside autonomous community | EMS nonspecialised team | Nondedicated ambulance. EMS incubators |

| Special cases: EMS + P/N | EMS helicopter | |||

| Andalusia Malaga | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within/outside autonomous community | EMS D/Nu trained in NT | Nondedicated ambulance. RH/EMS incubators |

| Transport between private facilities, Ceuta and Melilla to H. Málaga | Nonspecialised technicians | EMS helicopter | ||

| Physician/nursing staff trained in NT | ||||

| Murcia | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient requiring higher-level inpatient care. Within autonomous community | D/Nu trained in neonatal care | Nondedicated ambulance. Incubators in RH |

| EMS nonspecialised | EMS helicopter | |||

| Outside autonomous community | Special cases: EMS + P/N |

D/Nu: doctor/nurse; EMS, emergency medical services; NT, neonatal transport; PNT, paediatric and neonatal transport; P/N, paediatrician/neonatologist; RH, receiving hospital; SH, sending hospital.

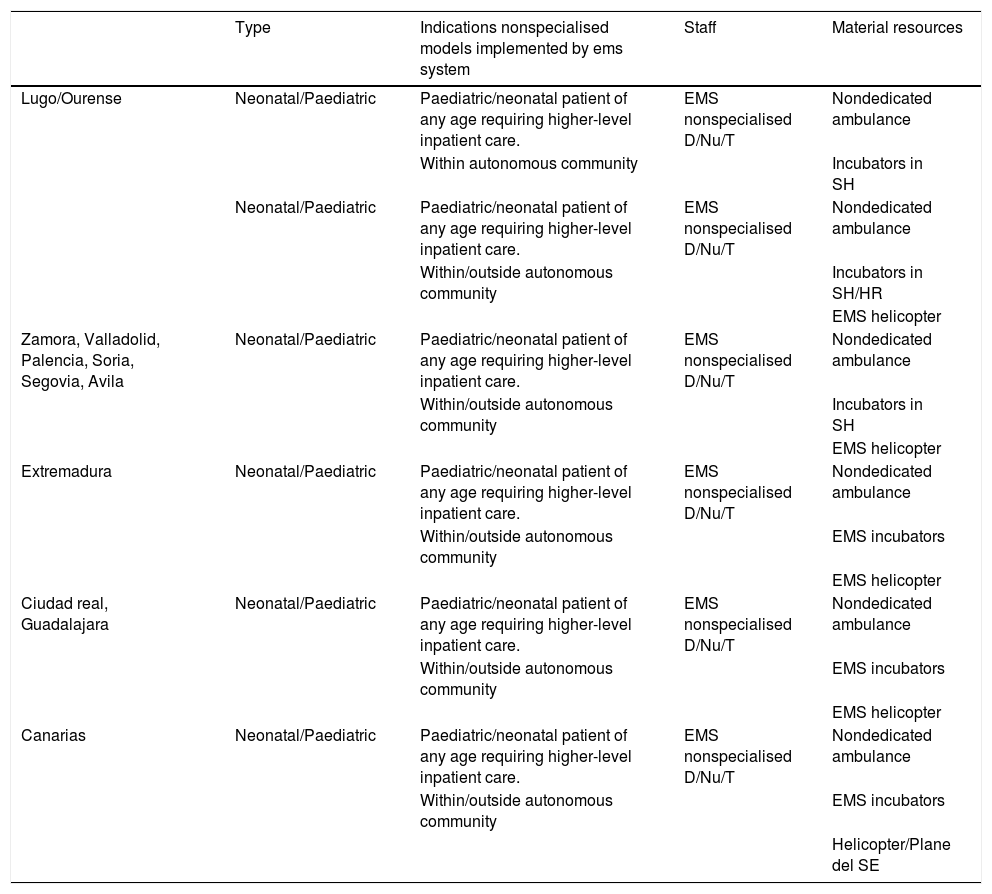

Nonspecialised PNT models in Spain implemented by EMS systems.

| Type | Indications nonspecialised models implemented by ems system | Staff | Material resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lugo/Ourense | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. | EMS nonspecialised D/Nu/T | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Within autonomous community | Incubators in SH | |||

| Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. | EMS nonspecialised D/Nu/T | Nondedicated ambulance | |

| Within/outside autonomous community | Incubators in SH/HR | |||

| EMS helicopter | ||||

| Zamora, Valladolid, Palencia, Soria, Segovia, Avila | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. | EMS nonspecialised D/Nu/T | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Within/outside autonomous community | Incubators in SH | |||

| EMS helicopter | ||||

| Extremadura | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. | EMS nonspecialised D/Nu/T | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Within/outside autonomous community | EMS incubators | |||

| EMS helicopter | ||||

| Ciudad real, Guadalajara | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. | EMS nonspecialised D/Nu/T | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Within/outside autonomous community | EMS incubators | |||

| EMS helicopter | ||||

| Canarias | Neonatal/Paediatric | Paediatric/neonatal patient of any age requiring higher-level inpatient care. | EMS nonspecialised D/Nu/T | Nondedicated ambulance |

| Within/outside autonomous community | EMS incubators | |||

| Helicopter/Plane del SE |

D/Nu/T: doctor/nurse/technician; EMS, emergency medical services; RH, receiving hospital; SH, sending hospital.

The transport of a critically ill paediatric patient does not consist solely of moving a patient from one location to another, but is a more complex process that allows adequate stabilization and involves the SH, the transport team, the receiving hospital and the coordinating facility through their collaboration. Thus, PNT makes available the human and material resources of a PICU or NICU to patients wherever they happen to be. Thus, PNT teams:

- -

Provide equipment and medication not available in lower-level hospitals and health care workers trained in their use: central vascular access line insertion and use, surfactant administration both postintubation and through minimally invasive methods; setup and delivery of nitric oxide12; non-invasive ventilation13,14 (high-flow nasal prongs, continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP]), which reduces the proportion of patients intubated for transport; ventilation interfaces appropriate for the size of paediatric/neonatal patients that are intubated or require high-frequency oscillatory ventilation15 (a modality applied nearly exclusively in neonatology/paediatrics and which requires experience for correct implementation).

- -

Allow transport of patients with paediatric illnesses that require specific management: late preterm infants16,17 (careful management in the first hours post birth can have an impact on long-term outcomes: prevention of hyperoxia/hypo- or hypercapnia, hypothermia, damage to the developing lung caused by the use of respiratory support, abrupt haemodynamic changes carrying a risk of cerebrovascular insult, etc); hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy18,19 (with a specific time window for initiation of therapeutic hypothermia to improve neurologic outcomes and requiring careful management of fluids, electrolytes and haemodynamic support); cardiac diseases, both congenital and acquired in the first years of life, etc.

- -

Allows transport of patients that need care that requires highly specific training, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)20,21 with the added peculiarities of infants and children compared to adults, and always with participation of other teams (surgeons, perfusionists, security/police, civil guard or armed forces).

- -

Allows transfer back to SH of patients that still require specialised care during transport. This type of transfer contributes to the optimization of health care resources and to improving the quality of life of patients and their families.

Other ways in which severely ill children would benefit from the availability of PNT include transport children with palliative care needs22 under the best possible conditions to their homes; support in primary transport23 (in some cases in person and in others remotely); phone or online consultation to guide the care of critically ill children when the staff managing the patient has questions regarding assessment or treatment; assisting in transfer coordination and the selection of the appropriate hospital, and training the rest of the staff of the EMS system on paediatric care.

Quality in PNT: human and material resourcesHuman resourcesGiven the competencies required for the IHT of critically ill children, the ideal PNT team would include a paediatrician or neonatologist and a paediatric nurse specifically trained in transport, in addition to an EMT trained in paediatric care. Another appropriate model would be a prehospital emergency care physician and nurse with a strong background in paediatric and neonatal care, which would probably require the development of an official training curriculum to ensure the necessary skills and competencies. The PNT team should be integrated in the EMS system of the corresponding autonomous community and be based off a tertiary care hospital to maintain the skills of its members and ensure adequate continuing education.

To guarantee the high-quality care required by critically ill children, resources in addition to the knowledge and skills found in a PICU or NICU are required, more specific to medical transport, that are not usually at play in high-level intensive care settings, such as teamwork in typically adverse environments with limited resources and added difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. Transport teams usually consist of 2–3 members (limited human resources) and frequently have to interact with other institutions with which shared care protocols have not been established. The physical space is limited. There are physiological processes related to transport that may have a negative impact on the patient, and due to potential interference with monitoring devices an adequate clinical assessment and stabilization need to be performed at the SH, where the care staff will have to rely on the few available diagnostic methods (bedside blood gas analysis and ultrasound). Communication skills are very important both for teamwork and to interact with families or with patients that, either due to age or illness, have difficulty understanding the situation. Leadership skills are also important in the individual in charge of the team, as is the delegation of tasks and the ability to envision patient transfer as a whole to identify opportunities for improvement and increase trust and rapport.

In this regard, some societies are already working on developing competency profiles, with the role of the physician being the most defined thus far,24,25 although defining the role of the remaining team members is equally important. According to the SECIP and the SENeo, the physician, ideally a paediatrician or neonatologist, should have the theoretical knowledge and clinical skills to deliver care at the same level as would be offered at a PICU or NICU: ability to intubate patients ranging from extremely preterm neonates to adolescents with a body weight of 70 kg, thorough knowledge of the haemodynamic support required in the case of sepsis in a preterm infant or meningococcal sepsis in a child, differential diagnosis skills to correctly select the receiving hospital, and the necessary communication skills to convey to parents that transport may be life-threatening. Nursing staff must have experience caring for critically ill patients and be able to work in small teams and without the support of other nurses with comparable skills and training, among other requirements. Both physicians and nurses must have the skills required for medical transport. Emergency medical technicians are largely responsible to ensure the safety of the team, must be able to operate a broad range of medical devices and know all the paediatric supplies and equipment used in stabilization to be able to help with advanced life support (which is particularly relevant in patients requiring respiratory or haemodynamic stabilization during transport in case complications develop, such as the need of intubation or the management of shock or cardiac arrest). Every member of the team must be a self-learner seeking to continuously improve.

At present there is no subspeciality or formal educational pathway that covers all of the requirements for PNT. However, it is clear that the delivery of quality care to critically ill children should not be left to chance and the possibilities found in available resources to cover gaps in competencies, but that there should be specific structures, such as specialised PNT, to guarantee it on a regular basis and within the appropriate framework. Paediatric and neonatal transport units, as we have been discussing, are true “teams”.

Continuing education is also a necessity to maintain existing skills and add new ones through different methods, including simulation team training.26 This approach is still not widely applied to PNT.

Paediatric neonatal transport must be integrated in the EMS system so that the most appropriate transport resources are allocated to each child. For example, in the case of an accident leading to traumatic injury and possibly need of surgery, the patient may most benefit from allocation of the closest medical transport, even if it is not specialised, or a combination of both. In other cases, if the patient is not critically ill, it may be preferable to reserve the PNT unit due to the scarcity of this resource. The characteristics of the life support units that are not specific for PNT, the competencies of their staff and the desirable framework to provide access to them are beyond the scope of this article.

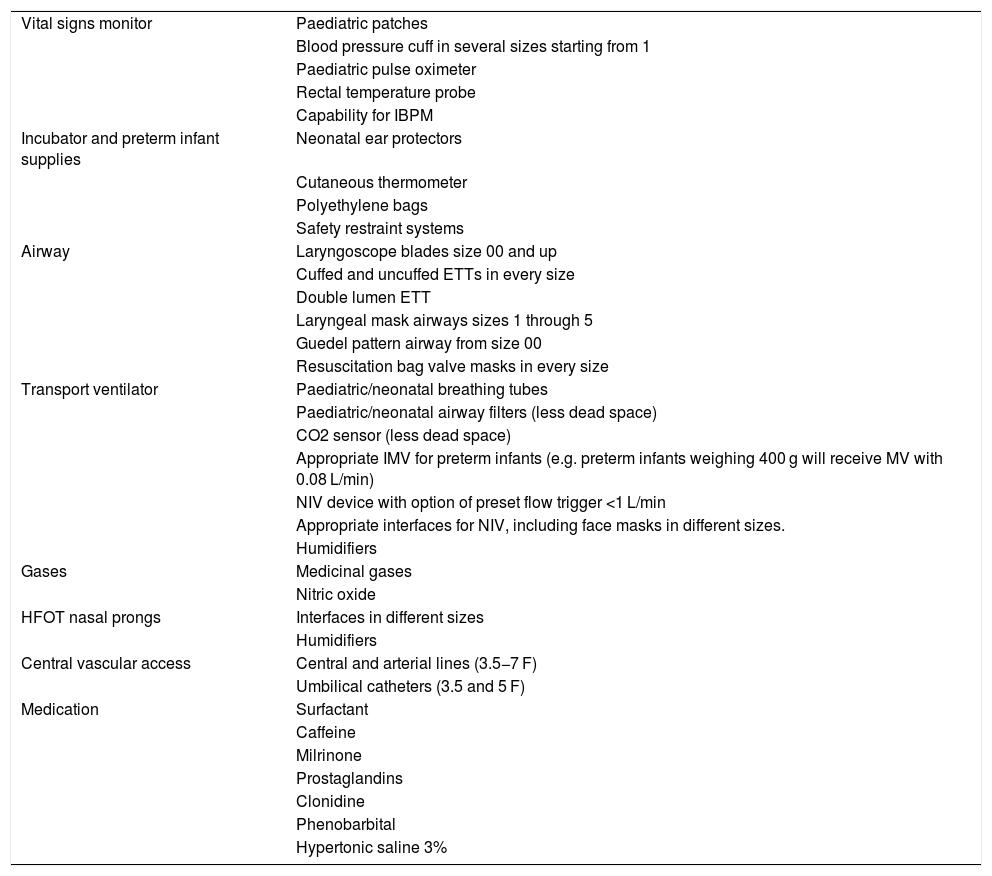

Material resourcesEquipment and vehicles in the transport unitRegulations on the technical characteristics, medical equipment and staffing of ground ambulances27 establish a general legal framework without specific details on the requirements for PNT. Therefore, we wrote this section based on the current literature and the experience in PNT domestically and abroad.

Paediatric and neonatal transport units should ideally have dedicated ambulances stocked with all the equipment and supplies that could be required for stabilization and transport. Since their patients span the entire paediatric age range, this entails a broad variety of equipment (Table 3). As an alternative, equipment could be packed in bags or cases and loaded in the ambulance allocated to each transport, which would add to the response time. In some cases, for instance transport in fixed-wing or rotor-wing aircraft, this is the only option, as air ambulances are also used to transport adult patients.

Durable and disposable equipment and supplies that are frequently unavailable in advanced life support units.

| Vital signs monitor | Paediatric patches |

| Blood pressure cuff in several sizes starting from 1 | |

| Paediatric pulse oximeter | |

| Rectal temperature probe | |

| Capability for IBPM | |

| Incubator and preterm infant supplies | Neonatal ear protectors |

| Cutaneous thermometer | |

| Polyethylene bags | |

| Safety restraint systems | |

| Airway | Laryngoscope blades size 00 and up |

| Cuffed and uncuffed ETTs in every size | |

| Double lumen ETT | |

| Laryngeal mask airways sizes 1 through 5 | |

| Guedel pattern airway from size 00 | |

| Resuscitation bag valve masks in every size | |

| Transport ventilator | Paediatric/neonatal breathing tubes |

| Paediatric/neonatal airway filters (less dead space) | |

| CO2 sensor (less dead space) | |

| Appropriate IMV for preterm infants (e.g. preterm infants weighing 400 g will receive MV with 0.08 L/min) | |

| NIV device with option of preset flow trigger <1 L/min | |

| Appropriate interfaces for NIV, including face masks in different sizes. | |

| Humidifiers | |

| Gases | Medicinal gases |

| Nitric oxide | |

| HFOT nasal prongs | Interfaces in different sizes |

| Humidifiers | |

| Central vascular access | Central and arterial lines (3.5−7 F) |

| Umbilical catheters (3.5 and 5 F) | |

| Medication | Surfactant |

| Caffeine | |

| Milrinone | |

| Prostaglandins | |

| Clonidine | |

| Phenobarbital | |

| Hypertonic saline 3% |

ETT, endotracheal tube; F, French; HFOT, high-flow oxygen therapy; IBPM, invasive blood pressure monitoring; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation, NIV, non-invasive ventilation.

In some instances, paediatric ambulances need to have a greater capacity than regular ambulances (box body ambulances)28 due to the amount of material that they need to transport on account of the wide range of patient sizes and of resources that may be required.

Helicopters are used to transport patients with time-dependent disease, when the distance to the receiving facility is long or if there are geographical or temporal barriers to transport. Fixed-wing ambulances are less flexible than rotor-wing ambulances, can cover long distances in a short time and usually have pressurized cabins. Teams that carry out patient transports in air ambulances must receive specific training. All the medical equipment must be certified for use in air ambulances.

Documentation during transportIn addition to the usual patient transport reports and a patient identification system, PNT requires informed consent.29,30

Anything that takes place during stabilization and transport must be documented in the health record of the patient. To this end, a specific format could be established for patient transport reports to allow planning and anticipate interventions in the event of potential complications, facilitate the transfer of information to the staff of the receiving facility and collect data for quality metrics.4,31

As is the case in any medical intervention, informed consent should be obtained prior to transport, although in high-risk situations verbal authorization could be obtained from parents or legal guardians to avoid delays. Informed consent includes explaining any techniques or treatments that may be used during stabilization or transport and the intrinsic risks of medical transport (those directly associated with it, such as the risk of a motor vehicle collision, risks associated with the physiological changes that take place during transport and risks related to the particular condition of the patient).30,32

Humanisation of careFamily-centred care has emerged as a standard in paediatric critical care. Although the presence of parents during resuscitation and while the child stays in hospital is endorsed by numerous scientific societies worldwide, there is no firm recommendation presence in PNT. In fact, parental presence in paediatric IHT is just starting to gain traction, and not only in Spain.33,34 This can be explained by the potential disadvantages that health professionals attribute to parental accompaniment, including organizational problems (lack of space, legislation and insurance), potential increase in parental anxiety, fear that the presence of parents may affect care delivery and medical and legal concerns of transport team members.35 Despite these drawbacks, accompanying the child lessens parental anxiety, improves collaboration in the awake child, fosters an enhanced sense of parental involvement in the child’s care and makes it possible for parents to stay informed of the condition of the child in real time. In most instances, transport teams have a neutral or positive perception of parental presence.34,36 The data on the perception of children at the time of transport are very scarce. Eighty-four percent of children aged 5–17 years consider being accompanied by their parents important, and therefore their opinion should be taken into account in decision-making.35

Allowing the presence of parents in PNT is the first step to promote family-centred care in transport teams, especially in ground transport. Outside the specific transport setting of helicopters, for which strong recommendations have yet to be established, studies to date show minimal impact on health care worker stress levels, and the benefits to patients and parents outweigh the risks.37

Quality indicatorsAs is the case in any other field of health care, a strategic and action plan is necessary to improve care delivery in PNT based on quality indicators. At the international level, there are several systems38,39 with established quality metrics that also allow comparison of different transport systems. In Spain, in 2018, a nationwide multicentre study was performed and resulted in the selection of 15 indicators to represent the needs of PNT in the country40 that have since been applied by different transport teams. This allows the comparison of PNT systems both in Spain and at the international level and contributes to the improvement of each transport.

ConclusionCritically ill children of any age are entitled to high-quality medical transport. To ensure this right, PNTs should be established throughout the Spanish territory which, despite possible variations in its composition, must meet basic standards in human and material resources. The implantation and integration of PNTs in EMS systems will also contribute to optimising their performance.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Millán García del Real N, Sánchez García L, Ballesteros Diez Y, Rodríguez Merlo R, Salas Ballestín A, Jordán Lucas R, et al. Importancia del transporte pediátrico y neonatal especializado. Situación actual en España: Hacia un futuro más equitativo y universal. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;95:485.