We conducted a prospective quasi-experimental study with the aim of assessing the perceived quality of life (QoL) and burden of caregivers of pediatric patients with dysphagia undergoing a specific assessment and treatment program.

MethodsThe study included pediatric patients aged less than 14 years with a diagnosis of dysphagia managed in a specialized unit. Patients underwent clinical assessments, including an oral motor assessment and diagnostic tests such as videofluoroscopy. Individualized rehabilitative treatment was initiated, including dietary modifications and rehabilitation approaches. Quality of life was evaluated by means of validated tools, including the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Family Impact Module (PedsQL-FIM) and an adapted version of the Swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire (SwalQOL).

ResultsA total of 117 patients were recruited initially, and the final analysis included 99 patients. We observed significant improvements in dysphagia severity, oral diet expansion and safety outcomes after treatment. Caregivers of patients with greater neurological impairment, particularly those with GMFCS IV-V and using feeding tubes, were more likely to have higher post-intervention PedsQL-FIM scores.

ConclusionOur findings underscore the significant impact of dysphagia on caregiver QoL and the effectiveness of individualized rehabilitation programs in improving patient outcomes and mitigating caregiver burden. Future research should focus on refining assessment tools and enhancing comprehensive care approaches to further support caregivers and patients in managing dysphagia.

Este estudio prospectivo cuasiexperimental tuvo como objetivo evaluar la percepción de la calidad de vida (CV) y la carga del cuidador en pacientes pediátricos con disfagia sometidos a un programa específico de evaluación y tratamiento.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron pacientes pediátricos menores de 14 años diagnosticados con disfagia que asistieron a una unidad especializada. Los pacientes fueron sometidos a evaluaciones clínicas, incluyendo examen oromotor y pruebas complementarias como videofluoroscopia. Se inició un tratamiento rehabilitador individualizado, que incluyó adaptaciones dietéticas y maniobras rehabilitadoras. La evaluación de la CV se realizó mediante herramientas validadas, incluyendo el Módulo de Impacto Familiar del Inventario de Calidad de Vida Pediátrica (PedsQL-FIM) y una versión adaptada del Cuestionario de Calidad de Vida en la Deglución (SwalQL).

ResultadosSe incluyeron inicialmente 117 pacientes, de los cuales 99 fueron finalmente analizados. Se observaron mejoras significativas en la gravedad de la disfagia, la ampliación de la dieta oral y los resultados de seguridad tras el tratamiento. Los cuidadores de pacientes con mayor afectación neurológica, particularmente aquellos con GMFCS IV-V y sondas de alimentación, tenían una mayor probabilidad de obtener puntuaciones más altas en el PedsQL-FIM tras la intervención.

ConclusionesEste estudio destaca el impacto significativo de la disfagia en la CV de los cuidadores y la efectividad de los programas de rehabilitación individualizados en la mejora de los resultados de los pacientes y la reducción de la carga del cuidador. Las investigaciones futuras deberían centrarse en perfeccionar las herramientas de evaluación y en mejorar los enfoques de atención integral para apoyar a cuidadores y pacientes en el manejo de la disfagia.

Swallowing begins with the formation of the bolus in the oral cavity and ends when the bolus reaches the stomach after a series of coordinated functions, including suction, swallowing and airway protection, which require precise neurological control.1 Dysphagia refers to an alteration in any of the phases of this process (oral, pharyngeal or esophageal).

The incidence of pediatric dysphagia is less than 1%,2 but it increases in at-risk groups, such as children with neurological diseases, craniofacial anomalies, cardiopulmonary diseases or prematurity.3 Some series report a prevalence of 93.8% in specific populations,4 depending on the applied definitions and inclusion criteria. It is worth noting that approximately 25% of children with swallowing disorders have normal development,5 which suggests a diverse etiology and a higher prevalence than initially assumed.

Dysphagia significantly affects health and quality of life (QoL), limiting social participation and causing complications such as malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia.6 Prior research has highlighted the nutritional challenges faced by these children, particularly regarding caloric intake and dietary modifications.7 However, the impact on caregivers’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) remains underexplored. Early diagnosis and tailored interventions are essential to ensure optimal child development. Furthermore, swallowing disorders disrupt family routines and social interactions at mealtimes, with a deleterious impact on daily activities critical for growth.

A comprehensive evaluation of pediatric dysphagia is essential for the purpose of individualizing treatment, improving feeding skills and mitigating caregiver burden. The aim of our study was to assess the impact of an individualized oral motor rehabilitation program on pediatric health and HRQoL. To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined this issue comprehensively in a pediatric context. The perspective of our study could contribute significantly to improving the management of these patients.

Material and methodsStudy design and participantsWe conducted a prospective, quasi-experimental study in pediatric patients aged less than 14 years with a confirmed diagnosis of dysphagia. Participants were evaluated and managed at a specialized pediatric dysphagia unit between July 2020 and September 2022. The severity of dysphagia was categorized based on its impact on feeding efficiency and safety. The assessments included a detailed oral motor evaluation, direct observation of feeding behaviors and the use of additional diagnostic tools such as videofluoroscopy (VFS) as needed. After diagnosis, an individualized rehabilitation plan was made for each patient and subsequently implemented under the supervision of a speech and language therapist. We collected data systematically for relevant epidemiological, anthropometric, and clinical variables, assessing the level of medical complexity by means of the PedCom scale8 for the identification of pediatric chronic complex patients.

Assessment toolsDysphagia severity was evaluated using the Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) (including pediatric versions)9–11 and the Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS)/mini-EDACS scales,12,13 with the addition of the Penetration Aspiration Scale (PAS) in patient assessed by VFS.14 These assessment tools have been used previously in pediatric dysphagia research to classify severity and guide nutritional management.7 Videofluoroscopic swallowing studies followed a standardized protocol with administration of iodinated contrast (Visipaque). Video was recorded at 15 frames per second under controlled conditions.

Quality of life was assessed using the PedsQL-FIM (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Family Impact Module) after obtaining the license for its use (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org)15 and an adapted version of the Swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire (SwalQoL), which had exhibited good reliability in a pilot study.16

Oral motor rehabilitation trainingRehabilitative strategies combined compensatory and therapeutic approaches tailored to the patient’s age, pathology and level of cooperation. Compensatory techniques included dietary modifications, adapted utensils and postural changes during feeding. The rehabilitation strategies included manual therapy, sensory integration, orofacial exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation and swallowing-specific maneuvers.

Outcome measuresThe outcome measures included: (a) anthropometric measurements using the WHO growth charts as reference for children under 5 years of age and reference tables from national growth studies for older children; (b) respiratory data, including the severity of exacerbations; (c) feeding efficacy and safety reassessed with the FOIS and EDACS scales; (d) changes in QoL assessed with the PedsQL-FIM and SwalQoL instruments.

Statistical analysisWe conducted a descriptive analysis, calculating the mean and standard deviation or the median and interquartile range based on whether the data followed a normal distribution, which was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We compared categorical variables using the chi-square test and numerical variables with the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test as applicable. Subsequently, we used univariate logistic regression analysis to identify variables with a potential association, setting the selection threshold at P < .15. Subsequently, we fitted a multivariate logistic regression model including these variables in addition to variables deemed relevant based on theoretical or clinical reasons. We assessed the strength of the association strength through the calculation of odds ratios (OR) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We defined statistical significance as P < .05. All the analyses were performed with the SPSS software, version 24.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical considerationsEthical approval was obtained in adherence to institutional and international ethical standards for research. We obtained written informed consent and ensured patient confidentiality and the protection of personal data.

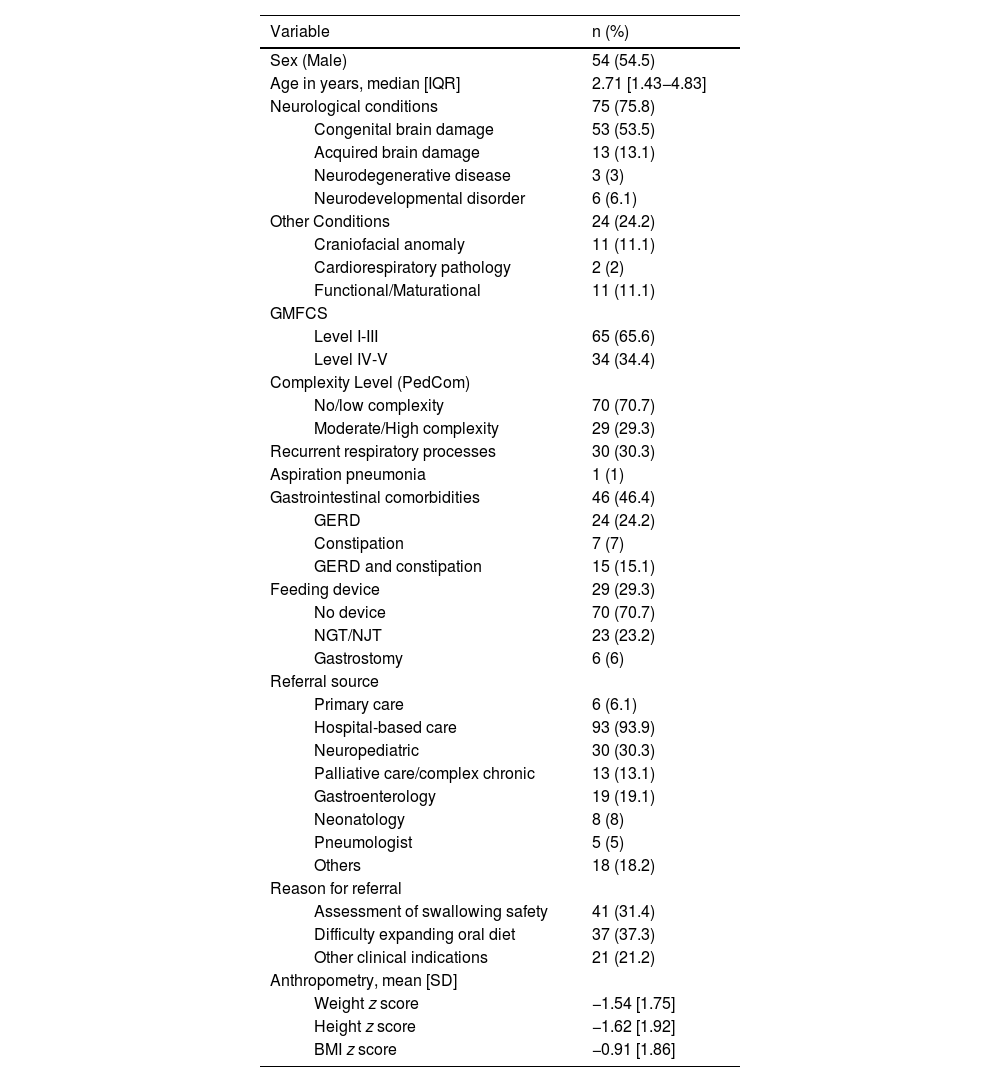

ResultsA total of 117 patients met the inclusion criteria, of who 99 were included in the analysis. The median duration of follow-up was 22.3 months (IQR, 16–26.7). During the study, four patients died, one was discharged due to improvement before the minimum follow-up period, and 13 patients were lost to follow-up due to relocation or neurological deterioration. This was consistent with the findings of a previous study addressing the nutritional implications of pediatric dysphagia.7Table 1 summarizes the main epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Epidemiological characteristics of the patients (n = 99).

| Variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (Male) | 54 (54.5) | |

| Age in years, median [IQR] | 2.71 [1.43−4.83] | |

| Neurological conditions | 75 (75.8) | |

| Congenital brain damage | 53 (53.5) | |

| Acquired brain damage | 13 (13.1) | |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 3 (3) | |

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | 6 (6.1) | |

| Other Conditions | 24 (24.2) | |

| Craniofacial anomaly | 11 (11.1) | |

| Cardiorespiratory pathology | 2 (2) | |

| Functional/Maturational | 11 (11.1) | |

| GMFCS | ||

| Level I-III | 65 (65.6) | |

| Level IV-V | 34 (34.4) | |

| Complexity Level (PedCom) | ||

| No/low complexity | 70 (70.7) | |

| Moderate/High complexity | 29 (29.3) | |

| Recurrent respiratory processes | 30 (30.3) | |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 1 (1) | |

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | 46 (46.4) | |

| GERD | 24 (24.2) | |

| Constipation | 7 (7) | |

| GERD and constipation | 15 (15.1) | |

| Feeding device | 29 (29.3) | |

| No device | 70 (70.7) | |

| NGT/NJT | 23 (23.2) | |

| Gastrostomy | 6 (6) | |

| Referral source | ||

| Primary care | 6 (6.1) | |

| Hospital-based care | 93 (93.9) | |

| Neuropediatric | 30 (30.3) | |

| Palliative care/complex chronic | 13 (13.1) | |

| Gastroenterology | 19 (19.1) | |

| Neonatology | 8 (8) | |

| Pneumologist | 5 (5) | |

| Others | 18 (18.2) | |

| Reason for referral | ||

| Assessment of swallowing safety | 41 (31.4) | |

| Difficulty expanding oral diet | 37 (37.3) | |

| Other clinical indications | 21 (21.2) | |

| Anthropometry, mean [SD] | ||

| Weight z score | −1.54 [1.75] | |

| Height z score | −1.62 [1.92] | |

| BMI z score | −0.91 [1.86] | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; F, female; GERD, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; IQR, interquartile range; M, male; NGT, nasogastric tube; NJT, nasojejunal tube; PedCom, Scale for the identification of the complex chronic pediatric patient; SD, standard deviation.

Note: The sample has been described previously in Ortiz Pérez et al (2024) (7), with modifications in variable categorization and additional analyses specific to this study.

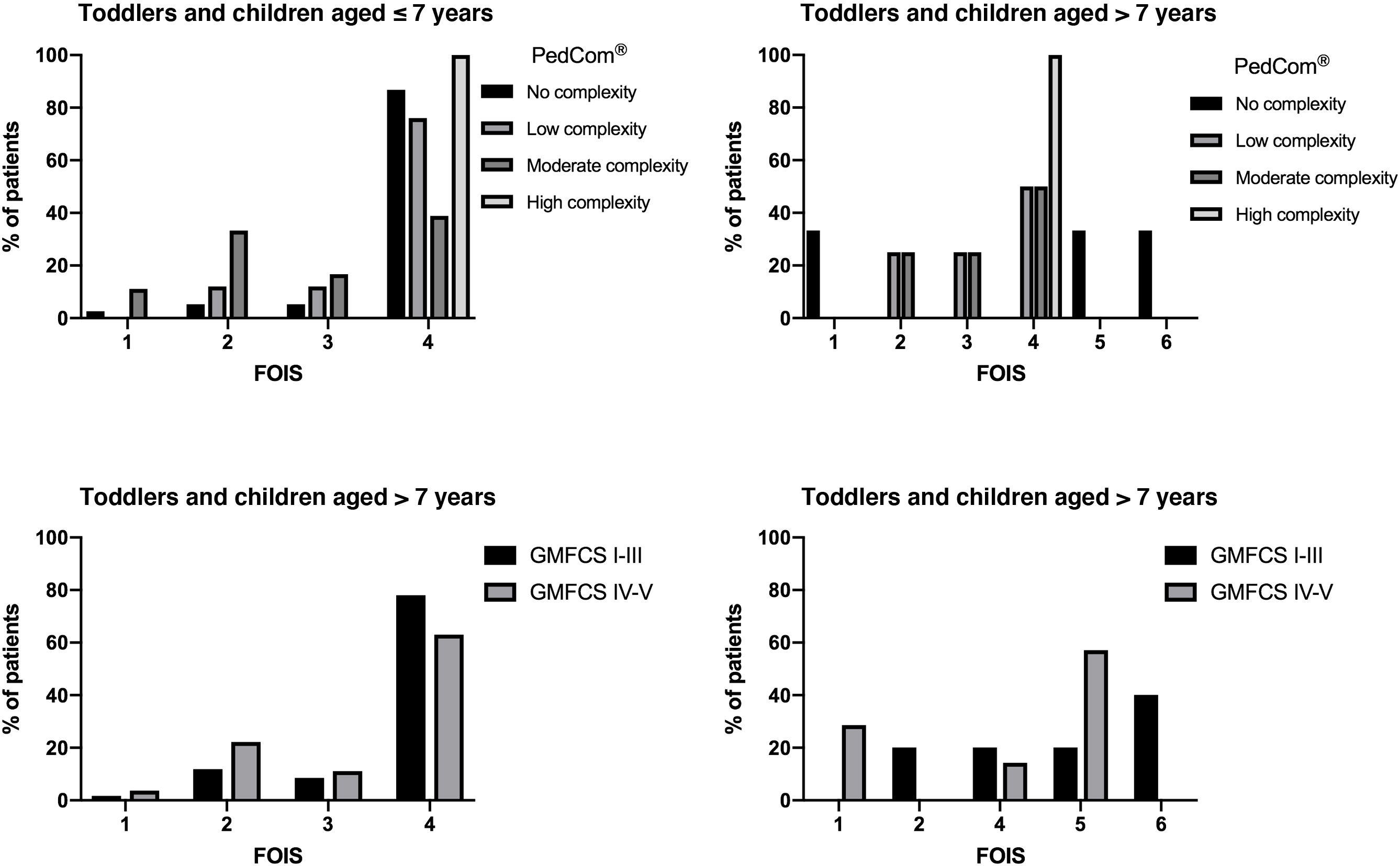

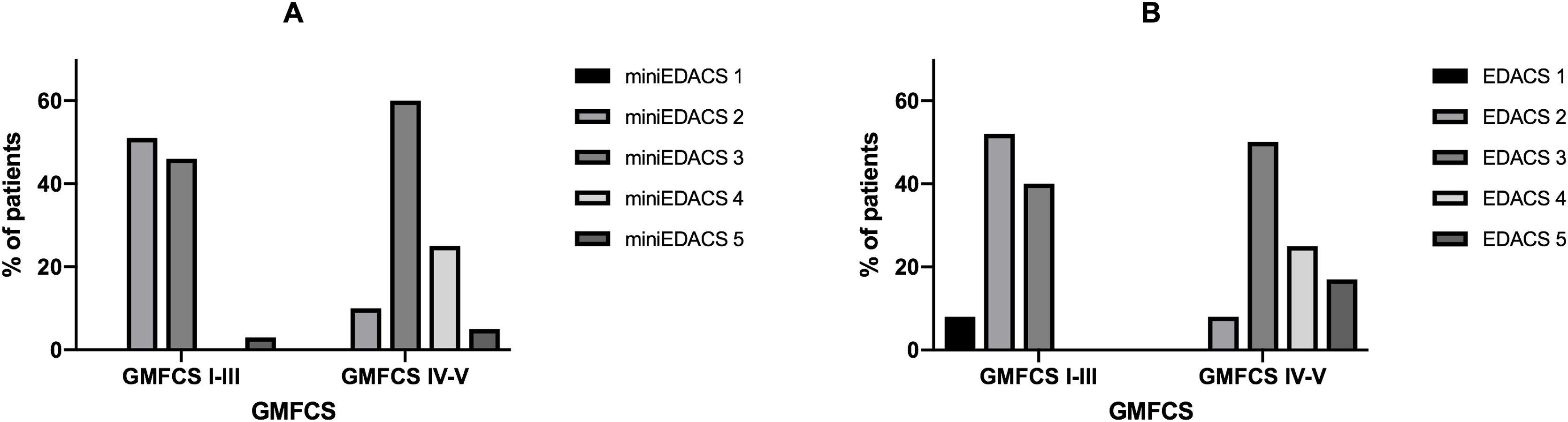

The assessment of dysphagia was made with age-appropriate scales (Fig. 1). In children aged less than 7 years, the most frequent score in the FOIS was 4 (72.4%), which corresponds to exclusive oral feeding with dietary modifications or incomplete oral diet expansion. In children aged more than 7 years, the most frequent score was 5 (38.5%). Significant differences were observed between FOIS levels in medical complexity assessed with the PedCom (r = −0.34; P = .002), but not in the classification in GMFCS groups. The EDACS safety scale and mini-EDACS for children under 36 months showed significant correlations with motor impairment (r = 0.583 [P < .001] and r = 0.441 [P < .001], respectively) and complexity (r = 0.43 [P < .005] and r = 0.492 [P < .001], respectively). Greater impairment and complexity correlated to more severe dysphagia (Fig. 2).

Correlation between scores in dysphagia severity scale EDACS and gross motor impairment. (A) Children under 36 months (B) Children over 36 months. EDACS: Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System; miniEDACS: adaptation for children between 18-36 months. EDACS 1: eats and drinks safely and efficiently; EDACS 2: eats and drinks safely with effectiveness limitations; EDACS 3: eats and drinks with some safety limitations; EDACS 4: eats and drinks with significant safety limitations; EDACS 5: unable to eat and drink safely orally.

Thirty-seven patients were evaluated with VFS, and the results were abnormal in 86.5%: 50% had mixed oral and pharyngeal involvement, and 7.6% had isolated pharyngeal involvement. Aspiration occurred in 41% of the patients and was silent in 66.7% of these cases. Higher GMFCS scores were associated with higher PAS scores (r = 0.455; P < .05), and higher complexity, although the latter association was not significant.

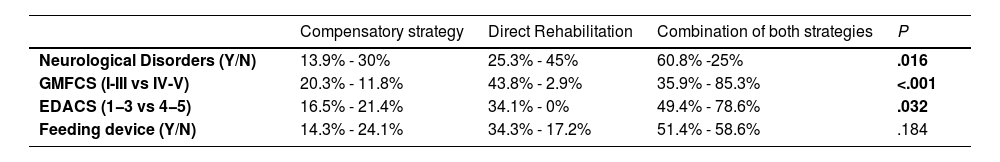

Rehabilitative approaches included compensatory and direct interventions, as detailed in Table 2. Patients with neurological disorders were predominantly managed with combined approaches. Severe safety impairments required ore dietary modification more frequently (P = .032). During the follow-up, 58% of patients had no respiratory exacerbations, 39% had mild episodes, and only one required hospitalization for pneumonia

Rehabilitation strategies by underlying pathology, motor function classification (GMFCS), feeding safety scale (EDACS), and external feeding support.

| Compensatory strategy | Direct Rehabilitation | Combination of both strategies | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological Disorders (Y/N) | 13.9% - 30% | 25.3% - 45% | 60.8% -25% | .016 |

| GMFCS (I-III vs IV-V) | 20.3% - 11.8% | 43.8% - 2.9% | 35.9% - 85.3% | <.001 |

| EDACS (1−3 vs 4−5) | 16.5% - 21.4% | 34.1% - 0% | 49.4% - 78.6% | .032 |

| Feeding device (Y/N) | 14.3% - 24.1% | 34.3% - 17.2% | 51.4% - 58.6% | .184 |

EDACS, Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System. Values are presented as percentages. (Y/N):Yes category/No category. Data adapted from Ortiz Pérez et al (2024)7 with restructured variable groupings.

We observed significant improvement in the severity of dysphagia, reflected by an increase in FOIS scores in children aged less than 7 years (P < .001). In older children, we observed an upward trend in FOIS scores, although it did not reach statistical significance, suggesting a tendency toward oral diet expansion. In addition, the severity of dysphagia measured with the EDACS showed a significant reduction in both children aged less than 36 months (P < .05) and older children (P < .05). Notably, 53.6% of patients who initially required enteral feeding via feeding tubes transitioned to partial or exclusive oral feeding after the intervention.

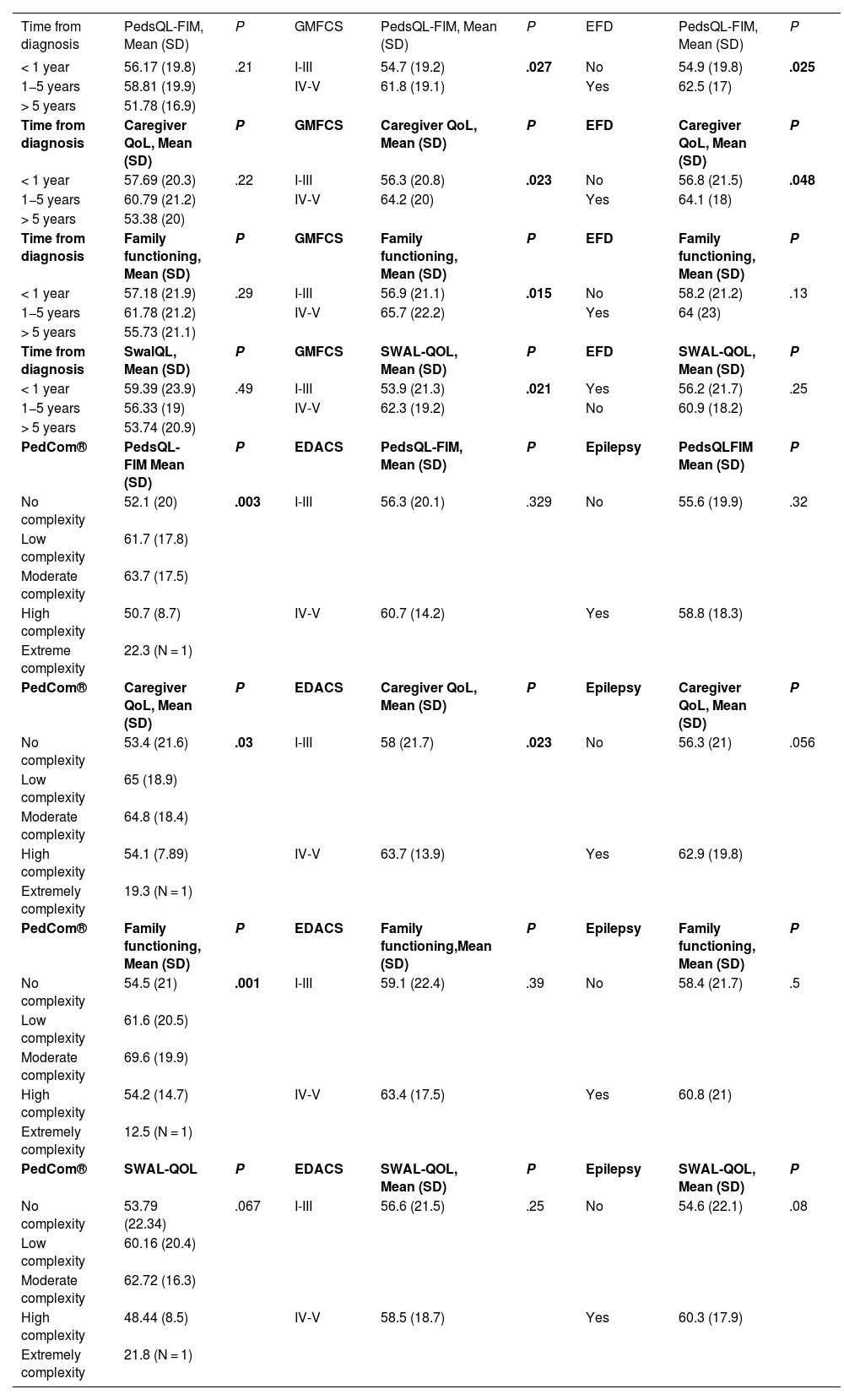

In the analysis of QoL, we compared PedsQL-FIM scores based on age, complexity, severity and the use of feeding devices. We found lower scores were in the worry and daily activities domains (Table 3). Greater motor impairment correlated with better scores in family functioning, caregiver QoL and total PedsQL-FIM scores (P = .015, P = .023 and P = .027, respectively). Caregivers of patients with severe swallowing safety issues (P = .023) or feeding devices (P = .048) had higher QoL scores.

Results on family (PedsQ-FIM) and caregiver’s quality of life according to adapted SWAL-QoL based on baseline situation (disease progression time, degree of gross motor impairment, level of complexity of chronic patient, presence or absence of external feeding device, and presence or absence of epilepsy).

| Time from diagnosis | PedsQL-FIM, Mean (SD) | P | GMFCS | PedsQL-FIM, Mean (SD) | P | EFD | PedsQL-FIM, Mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 year | 56.17 (19.8) | .21 | I-III | 54.7 (19.2) | .027 | No | 54.9 (19.8) | .025 |

| 1−5 years | 58.81 (19.9) | IV-V | 61.8 (19.1) | Yes | 62.5 (17) | |||

| > 5 years | 51.78 (16.9) | |||||||

| Time from diagnosis | Caregiver QoL, Mean (SD) | P | GMFCS | Caregiver QoL, Mean (SD) | P | EFD | Caregiver QoL, Mean (SD) | P |

| < 1 year | 57.69 (20.3) | .22 | I-III | 56.3 (20.8) | .023 | No | 56.8 (21.5) | .048 |

| 1−5 years | 60.79 (21.2) | IV-V | 64.2 (20) | Yes | 64.1 (18) | |||

| > 5 years | 53.38 (20) | |||||||

| Time from diagnosis | Family functioning, Mean (SD) | P | GMFCS | Family functioning, Mean (SD) | P | EFD | Family functioning, Mean (SD) | P |

| < 1 year | 57.18 (21.9) | .29 | I-III | 56.9 (21.1) | .015 | No | 58.2 (21.2) | .13 |

| 1−5 years | 61.78 (21.2) | IV-V | 65.7 (22.2) | Yes | 64 (23) | |||

| > 5 years | 55.73 (21.1) | |||||||

| Time from diagnosis | SwalQL, Mean (SD) | P | GMFCS | SWAL-QOL, Mean (SD) | P | EFD | SWAL-QOL, Mean (SD) | P |

| < 1 year | 59.39 (23.9) | .49 | I-III | 53.9 (21.3) | .021 | Yes | 56.2 (21.7) | .25 |

| 1−5 years | 56.33 (19) | IV-V | 62.3 (19.2) | No | 60.9 (18.2) | |||

| > 5 years | 53.74 (20.9) | |||||||

| PedCom® | PedsQL-FIM Mean (SD) | P | EDACS | PedsQL-FIM, Mean (SD) | P | Epilepsy | PedsQLFIM Mean (SD) | P |

| No complexity | 52.1 (20) | .003 | I-III | 56.3 (20.1) | .329 | No | 55.6 (19.9) | .32 |

| Low complexity | 61.7 (17.8) | |||||||

| Moderate complexity | 63.7 (17.5) | |||||||

| High complexity | 50.7 (8.7) | IV-V | 60.7 (14.2) | Yes | 58.8 (18.3) | |||

| Extreme complexity | 22.3 (N = 1) | |||||||

| PedCom® | Caregiver QoL, Mean (SD) | P | EDACS | Caregiver QoL, Mean (SD) | P | Epilepsy | Caregiver QoL, Mean (SD) | P |

| No complexity | 53.4 (21.6) | .03 | I-III | 58 (21.7) | .023 | No | 56.3 (21) | .056 |

| Low complexity | 65 (18.9) | |||||||

| Moderate complexity | 64.8 (18.4) | |||||||

| High complexity | 54.1 (7.89) | IV-V | 63.7 (13.9) | Yes | 62.9 (19.8) | |||

| Extremely complexity | 19.3 (N = 1) | |||||||

| PedCom® | Family functioning, Mean (SD) | P | EDACS | Family functioning,Mean (SD) | P | Epilepsy | Family functioning, Mean (SD) | P |

| No complexity | 54.5 (21) | .001 | I-III | 59.1 (22.4) | .39 | No | 58.4 (21.7) | .5 |

| Low complexity | 61.6 (20.5) | |||||||

| Moderate complexity | 69.6 (19.9) | |||||||

| High complexity | 54.2 (14.7) | IV-V | 63.4 (17.5) | Yes | 60.8 (21) | |||

| Extremely complexity | 12.5 (N = 1) | |||||||

| PedCom® | SWAL-QOL | P | EDACS | SWAL-QOL, Mean (SD) | P | Epilepsy | SWAL-QOL, Mean (SD) | P |

| No complexity | 53.79 (22.34) | .067 | I-III | 56.6 (21.5) | .25 | No | 54.6 (22.1) | .08 |

| Low complexity | 60.16 (20.4) | |||||||

| Moderate complexity | 62.72 (16.3) | |||||||

| High complexity | 48.44 (8.5) | IV-V | 58.5 (18.7) | Yes | 60.3 (17.9) | |||

| Extremely complexity | 21.8 (N = 1) |

EDACS, Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System; EFD, External Feeding Device; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; PedCom, Complex Chronic Pediatric Patient Scale; PedsQL-FIM, Pediatric Quality of Life-Family Impact Module; QoL, Quality of Life; SD, standard deviation; SWAL-QoL, adapted Swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire.

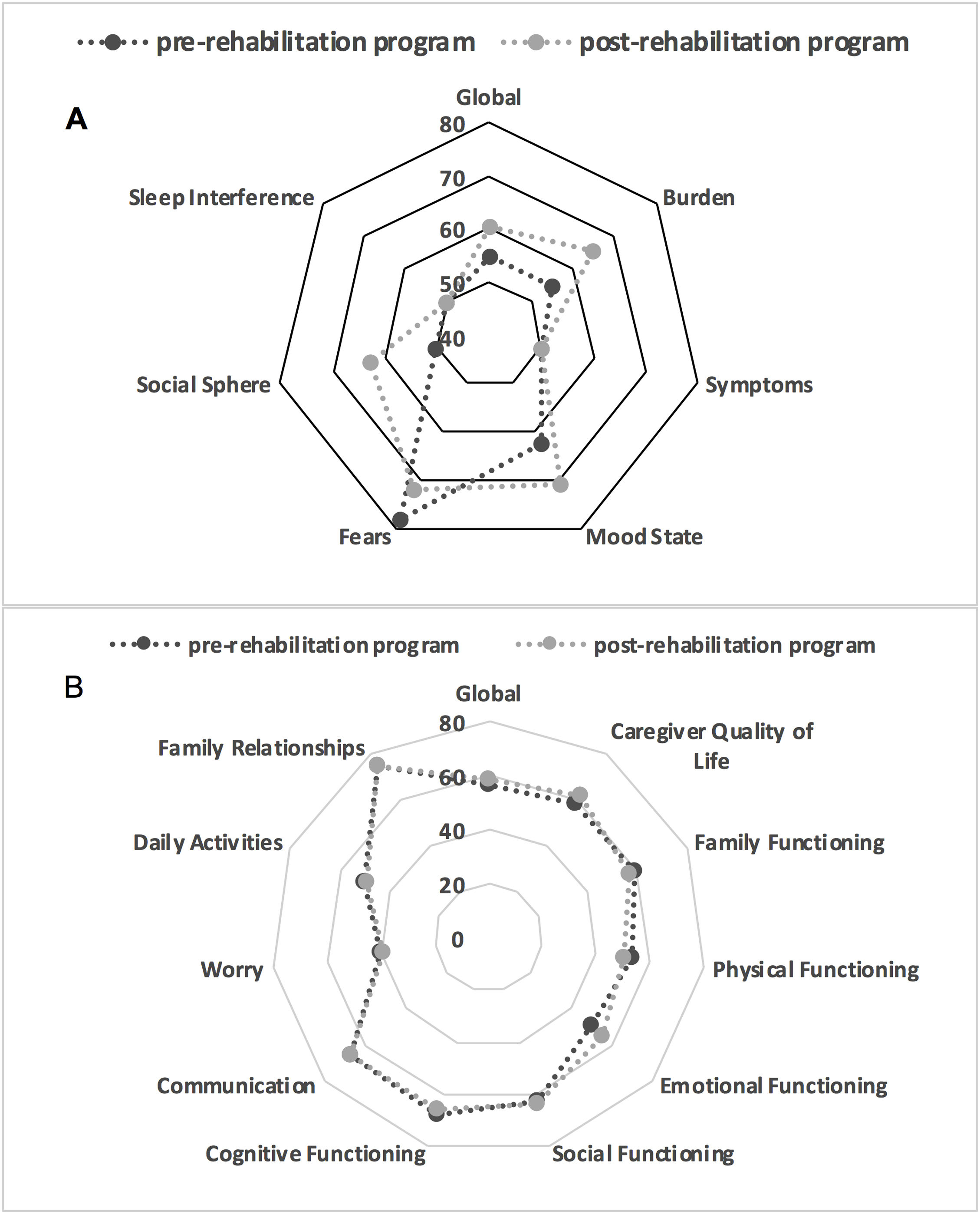

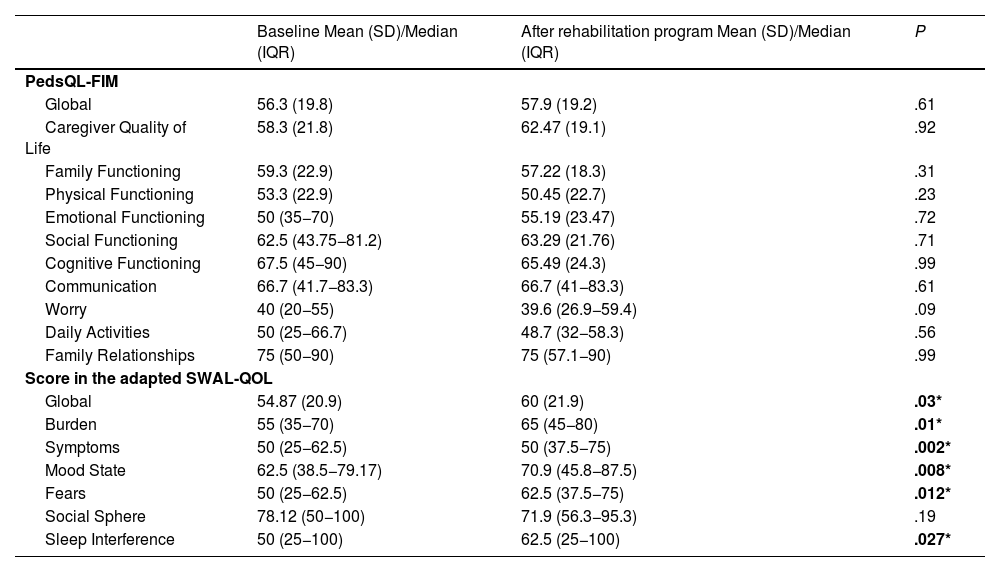

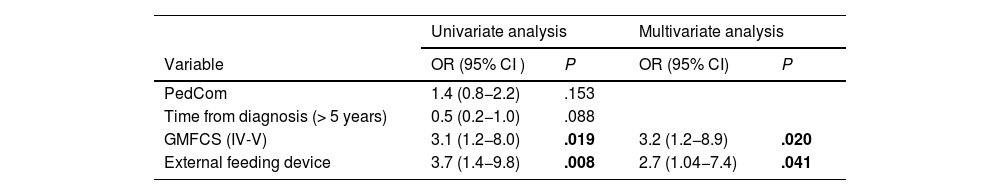

Comparisons in relation to treatment (Table 4) showed significant improvements in the adapted SWAL-QOL scores post-treatment, except in the social domain (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in PedsQL scores. Logistic regression (Table 5) indicated that caregivers of patients with GMFCS IV-V and who required feeding tubes were more likely to have higher post-intervention PedsQL-FIM scores.

Comparison of QoL questionnaire results before and after rehabilitation.

| Baseline Mean (SD)/Median (IQR) | After rehabilitation program Mean (SD)/Median (IQR) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PedsQL-FIM | |||

| Global | 56.3 (19.8) | 57.9 (19.2) | .61 |

| Caregiver Quality of Life | 58.3 (21.8) | 62.47 (19.1) | .92 |

| Family Functioning | 59.3 (22.9) | 57.22 (18.3) | .31 |

| Physical Functioning | 53.3 (22.9) | 50.45 (22.7) | .23 |

| Emotional Functioning | 50 (35−70) | 55.19 (23.47) | .72 |

| Social Functioning | 62.5 (43.75−81.2) | 63.29 (21.76) | .71 |

| Cognitive Functioning | 67.5 (45−90) | 65.49 (24.3) | .99 |

| Communication | 66.7 (41.7−83.3) | 66.7 (41−83.3) | .61 |

| Worry | 40 (20−55) | 39.6 (26.9−59.4) | .09 |

| Daily Activities | 50 (25−66.7) | 48.7 (32−58.3) | .56 |

| Family Relationships | 75 (50−90) | 75 (57.1−90) | .99 |

| Score in the adapted SWAL-QOL | |||

| Global | 54.87 (20.9) | 60 (21.9) | .03* |

| Burden | 55 (35−70) | 65 (45−80) | .01* |

| Symptoms | 50 (25−62.5) | 50 (37.5−75) | .002* |

| Mood State | 62.5 (38.5−79.17) | 70.9 (45.8−87.5) | .008* |

| Fears | 50 (25−62.5) | 62.5 (37.5−75) | .012* |

| Social Sphere | 78.12 (50−100) | 71.9 (56.3−95.3) | .19 |

| Sleep Interference | 50 (25−100) | 62.5 (25−100) | .027* |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PedsQL-FIM: Pediatric Quality of Life Family Impact Module; SD, standard deviation; SWAL-QOL, Swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Logistic regression: Probability of obtaining scores above the 70th percentile on the PedsQL-FIM quality of life scale.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI ) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| PedCom | 1.4 (0.8−2.2) | .153 | ||

| Time from diagnosis (> 5 years) | 0.5 (0.2−1.0) | .088 | ||

| GMFCS (IV-V) | 3.1 (1.2−8.0) | .019 | 3.2 (1.2−8.9) | .020 |

| External feeding device | 3.7 (1.4−9.8) | .008 | 2.7 (1.04−7.4) | .041 |

Hosmer and Lemeshow test: P = .929; Cox-Snell R2: 0.095. Nagelkerke R2: 0.148. The model was statistically significant, explained 0.095 to 0.148 of the variance of the dependent variable,and correctly classified 78.7% of cases.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; PedCom, Scale for the identification of the complex chronic pediatric patient; OR, odds ratio.

This study aimed to evaluate the perceived QoL and burden of caregivers of pediatric patients with dysphagia. Its results provide a more comprehensive view of the challenges caregivers face in this specific clinical context in which, in most cases, aspects related to chronicity and medical complexity compound the impact of dysphagia. The findings of the study are relevant for the purpose of improving medical care and humanizing caregiving, and it is important to consider the associated variables and their direct impact on caregiver QoL.

We observed strong covariance between greater gross motor impairment and the presence of external feeding devices, both of which were associated with increased caregiver burden but also an apparent improvement in perceived QoL. These results highlight specific areas of concern that may require more focused attention and suggest the presence of resilience factors that could be explored in future studies to improve our understanding of the complex interactions between the demands of caregiving and the ability of caregivers to adapt.

There is evidence that conducting a comprehensive evaluation of swallowing disorders, both in children17 and adults,18 in addition to individualized management in a specialized clinic, significantly improve patient outcomes. Previous research by our group has particularly emphasized the role of dietary modifications and enteral nutrition in mitigating nutritional deficits in children with dysphagia.7 The present study expands this perspective by examining the effects of rehabilitation programs on caregiver burden and quality of life.

A preliminary study published by our team19 found a correlation between the degree of motor impairment and the severity of dysphagia. Along the same lines, Bykova et al.20 suggested that the EDACS scale could also be used to identify the risk of aspiration in children with cerebral palsy (CP). The analysis of the correlation between the EDACS and PedCom scales had a broader scope, seeking to understand how dysphagia affects the pediatric population more comprehensively by considering both feeding functionality and overall patient complexity. All of this underscores the importance of continuing research on the subject with new lines of inquiry in order to appropriately validate and refine screening tools that can effectively guide ordering of more invasive diagnostic tests studies, such as VFS, thereby ensuring more efficient decision-making, particularly in patients with more complex medical conditions.

Both scales (FOIS and EDACS) have been reported as reliable tools for evaluating and even quantifying the progression of swallowing function in patients undergoing rehabilitation interventions,13,21 even in the pediatric population, as done by Sellers et al.12,13,22 Therefore, the clinically relevant changes detected in our study appear robust and could be extrapolated to similar populations, supported by the applicability and reliability of these scales over time.

In addition to increasing morbidity and mortality risk, dysphagia adds complexity to pediatric patients, especially those with multiple comorbidities, thus increasing caregiver burden and impacting QoL. This has been analyzed primarily in the adult population; for example, Davis et al.23 described that caregivers of stroke survivors seemed to experience burden directly related to the impact of dysphagia during meals. However, although caregivers feel a greater burden, how the patient-caregiver dyad manages the situation may be more relevant to burden than the shared perception of the problem. Thus, positivity could be a mechanism supporting the resilience of caregivers of chronic patients. A systematic review on the burden of dysphagia in caregivers of older adults24 revealed the lack of standardized measurement instruments to quantify its severity. Another review on adults with dysphagia25 concluded that 71% of caregivers experienced some level of burden directly related to swallowing difficulties, and the most frequently mentioned reasons were the need to make modifications in meal preparation, lifestyle changes, impacts on social life, lack of support, the use of feeding tubes and fear of airway aspiration. In pediatrics, previous studies on caregivers of patients with complex chronic conditions also report high physical, psychosocial, and even economic burdens26–28 that impact their own health and QoL. A study in children with acquired brain damage due to ischemic stroke29 found that, in the specific case of patients with dysphagia or associated oral motor impairment, 71.4% of caregivers explicitly reported burden.

Previous studies have analyzed in greater detail how swallowing disorders in adults affect the HRQoL of caregivers, reporting the impact and negative repercussions on activities of daily living and HRQoL.9,30 In young children (2–5 years old), Simione et al.25 analyzed how swallowing problems directly impact QoL and compared these results with other medical conditions. The authors observed that children with feeding difficulties had significantly lower HRQoL values compared to kidney transplant or acute liver failure patients. In contrast, the scores were more favorable compared to patients with cancer currently undergoing treatment or even patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Another study by the same group26 also highlighted that feeding disorders have an impact on the daily routine and social interaction of both children and their caregivers, that caregivers express a preference for therapeutic approaches that incorporate family-centered principles, and that the barriers they encounter similarly involved temporal, economic, accessibility, and lack of knowledge aspects.

In a German cohort of children with a history of prematurity and esophageal atresia, Bergmann et al.27 analyzed swallowing problems and their impact on caregivers' HRQoL using a questionnaire adapted from the SWAL-QOL. The authors found that 70% of patients did not report complications, except for the subgroup of children with associated neurological comorbidity (intracerebral hemorrhage and posterior CP), directly related to the stress of a disproportionate meal duration along with lack of appetite. The authors justify these results with a hypothetical adaptation of families to swallowing problems in patients who only have esophageal motor involvement and that, in those with cognitive impairment and deficits in oral motor skills, swallowing problems negatively impact quality of life and caregiver anxiety. A study analyzing the impact on HRQoL of family members of children perated for esophageal atresia using the PedsQL-FIM questionnaire found that patients with digestive symptoms labeled as dysphagia or feeding difficulties significantly contributed to the impact on the family, with lower total scores, to a greater degree than the respiratory problems characteristic of this etiological group.28 In Brazil, an assessment of HRQoL was performed in a sample of 95 caregivers of children with varying degrees of dysphagia using the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey (FS-IS) together with the PedsQL-FIM, as we did in our sample. The authors reported similar data to ours, as the group of patients with oral feeding had poorer scores compared to those with feeding tubes, which seems to corroborate other studies demonstrating caregivers' difficulties related to proper meal preparation requiring modification and/or the pressure to ensure a sufficient energy intake.27,28

As in other complex chronic medical conditions that demand ongoing resilience, caregivers in our series experienced an improvement in their QoL, reflecting a reduction in difficulties in daily activities and greater satisfaction with their role as caregivers. Research reflecting this adaptive capacity and the generation of positive emotional responses in the disease process has been published in relation to other clinical situations, such as childhood cancer31,32 or chronic diseases.33–36

The findings of our study suggest that, with individualized treatment and appropriate counseling, there is a trend toward improvement in caregivers’ perceived QoL. We believe that future adjustments to existing assessment tools would be necessary to capture underlying changes more accurately. Additionally, our study highlights the importance of directing efforts toward improving the humanization of care and implementing a holistic approach in the management of pediatric patients with chronic conditions. Future research could focus on adapting assessment tools or identifying specific areas to focus intervention strategies to achieve tangible improvements in caregivers' quality of life, thereby supporting patient-centered and comprehensive care.

The improvement in caregiver QoL observed in this study underscores the significant role of family-centered care approaches in managing pediatric dysphagia. The findings suggest that involving caregivers actively in the rehabilitation process not only addresses the clinical needs of the patient but also mitigates the psychosocial burden often associated with chronic feeding difficulties. This improvement reflects the potential for enhancing daily routines and reducing caregiver stress, thereby fostering a more positive home environment that supports the development of the child. Future interventions could benefit from incorporating structured family support programs, which may further strengthen these outcomes.

Despite these positive results, this study highlights certain limitations in existing evaluation tools, such as the PedsQL-FIM and SWAL-QOL, which may lack the sensitivity to capture nuanced changes in QoL and feeding safety across diverse pediatric populations. Developing new or refining existing assessment instruments tailored to this clinical context is essential to better quantify outcomes and guide clinical decision-making. Such tools could enable a more precise evaluation of the impact of specific therapeutic strategies and help clinicians identify subtle improvements that may not be evident with current methods.

By addressing both the caregiver’s role and the limitations of existing assessment tools, these findings advocate for a holistic approach to the management of pediatric dysphagia, emphasizing the importance of both patient- and family-related outcomes. Future research should focus on refining the validation and implementation of sensitive and specific assessment measures to better capture the comprehensive impact of rehabilitation programs on the lives of patients and their caregivers.

LimitationsThe study presented has certain limitations that should be considered in interpreting the results. First, the heterogeneity of the sample, covering a variety of pediatric conditions and different levels of complexity, may affect the generalization of the findings. Additionally, although the questionnaire used to assess family impact has been found to be useful, it may benefit from specific adjustments to address the particularities related to swallowing disorders more accurately. Future research could focus on the development of more specialized instruments to address the specific aspects concerning caregiving more accurately in families of pediatric patients with dysphagia.

ConclusionsThere is limited evidence on the QoL of caregivers of children with dysphagia. Our findings provide new insights that support the considerable impact on HRQoL and how, over time, caregivers develop adaptive mechanisms to mitigate the negative impact on their daily routine and social participation.

Caregivers of children with dysphagia often face significant challenges during meals, with tense dynamics that can generate an unfavorable feedback loop, exacerbating existing food aversions. In some instances, years pass before they receive appropriate feeding assistance. Considering psychosocial factors may help improve patient care and the QoL of their families.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We gratefully acknowledge the funding provided by Nutricia Spain (Advanced Medical Nutrition of the Danone Group), which made it possible to hire a speech therapist specialized in pediatric swallowing. This financial support was essential for the delivery of rehabilitation services to the pediatric patients that participated in the study.