The goal of screen health is to reduce the deleterious impact of the use of screens, digital content and connected devices (collectively known as the ‘Internet of Things’) and harmful design. That is, of any information, application, software or hardware that affects physical, mental, social, sexual or brain health. With this objective in mind, the screen health working group of the Health Promotion Committee of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) published the Family Digital Plan (FDP) online in 2022 based on the evidence available through 2021. The purpose of this article is to offer a review of the evidence published from 2021 and to determine whether changes need to be made to the recommendations of the FDP. It is reasonable to state that there is sufficient evidence supporting the association between screen time and the displacement of healthy lifestyle habits such as sleep, diet, physical activity and face-to-face social interactions. Furthermore, screen use also has an impact on cardiovascular risk, visual health, brain volume and quality of life. Its effects are greater in children, especially those aged less than six years, and in adolescents, as it interferes with neurodevelopment and affect integration and reduces the ability to regulate emotion. The Health Promotion Committee of the AEP considers several actions necessary: the revision of the recommendations of the FDP, declaring screen use a public health problem, improving the training of pediatricians to prevent and detect it, improving research on the use of screens in education and health care systems, the establishment of legislation by governments to protect health and development, and advocating for the requirement of rigorous research to demonstrate, from the early stages of design and development, that technological products or services are safe for the health and brain of the population.

El objetivo de la salud digital es disminuir el impacto del uso de pantallas, del contenido, de los objetos conectados a Internet o el llamado “Internet de las cosas” y del diseño perjudicial. Es decir, de toda información, aplicación, software o hardware que afecte a la salud física, mental, social, sexual y al cerebro. Con este objetivo, el grupo de trabajo de salud digital del Comité de Promoción de la Salud (CPS) de la Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP) publicó en formato web en el 2022 el Plan Digital Familiar ® (PDF), teniendo en cuenta la evidencia disponible hasta 2021. En este artículo, se plantea realizar una revisión a partir del año 2021, para valorar si es necesario realizar cambios en las recomendaciones del PDF. Se puede afirmar que existe suficiente evidencia en la relación del tiempo de exposición a pantallas y el efecto desplazamiento de los hábitos de vida saludables como el sueño, la alimentación, la actividad física y las relaciones sociales cara a cara. Por otro lado, también impacta en el riesgo cardiovascular, salud visual, volumen cerebral y calidad de vida. Los efectos aumentan en la edad pediátrica, especialmente en menores de seis años y en la adolescencia, al interferir en el neurodesarrollo, el establecimiento de una afectividad adecuada y disminuir la capacidad de gestión de las emociones. Desde el CPS de la AEP consideramos necesario que se lleven a cabo diversas actuaciones: la revisión de las recomendaciones del PDF, la declaración de un problema de salud pública, la necesidad de mejorar la formación de los pediatras para prevenir y detectar, mejorar la investigación en el uso de pantallas en el sistema educativo y en salud, la necesidad de medidas legislativas promovidas por los gobiernos para proteger la salud y el desarrollo y promover desde el diseño de los servicios tecnológicos la necesidad de demostrar por investigaciones rigurosas que sus servicios son inocuos para la salud y el cerebro de la población.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in 2016,1 and the Canadian Paediatric Society, in 20172 published position statements based on the available scientific evidence that were the first to address the impact of digital media on health. The AAP pioneered these efforts and was the first to publish recommendations for families.3

The goal of screen health is to reduce the deleterious impact of the use of screens, digital content and connected devices, that is, the so-called “Internet of Things”, and harmful design. That is, of any information, application, software or hardware that affects physical, mental, social, sexual or brain health. To this end, from a preventive standpoint, it is important to engage in the promotion of healthy lifestyle habits, early risk detection, adequate management of problematic use and prevention of complications. With this objective in mind, the screen health working group of the Health Promotion Committee of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) published the Family Digital Plan (FDP) online in 2022. The FDP summarizes recommendations for families by age group with the aim of reducing the adverse health effects of digital media. Most of the recommendations are for the entire family, with the aim of enabling parents to educate children using the most powerful tool at their disposal, which is modeling behavior.

A review like the one presented in this article is particularly relevant for several reasons: (1) the digital media environment is constantly changing; (2) publications on the subject may be contradictory, even within the scientific literature, and (3) new evidence has become available since the publication of the FDP. Among the latter, we must highlight the evidence generated by a growing number of clinical trials in which the intervention group undergoes a “digital detox”4 and the population-based ABCD study5 in adolescents currently underway in the United States. To this, we must add the information obtained in the context of real-world clinical practice, in which emerging risk situations are identified.6

In light of the above, we decided to review the recent literature to assess whether the recommendations of the FDP need to be revised. As a general rule and bearing in mind that these recommendations are aimed at the general population, in the absence of evidence on any given aspect, we recommend exercising caution.7

Screen use in children and adolescents in SpainScreen use before adolescenceTo get acquainted with the digital media use habits in the early stages of life, we consulted the results of a survey conducted in Spain.8 The mean daily screen time devoted to watching television (TV) and playing videogames was 71 minutes in children aged less than 2 years and 112.8 minutes in children aged 2 to 6 years. These data show that the population is not aware of pediatric recommendations. In this survey, a screen time of more than 2 hours a day was associated with: (1) children favoring the use of digital media over other leisure activities; (2) frequent use of devices during meals; (3) watching TV alone; (4) having TV playing in the background; (5) having a TV in the bedroom; (6) having 5 or more screens in the household; (7) parental screen time greater than 2 hours. This survey showed that screen time was lesser when adults were aware of the impact of technology on children’s health and the current evidence-based recommendations compared to families who did not have this information.

Screen use in adolescenceA survey published in 20219 analyzed social media use and associated risks in adolescents by means of validated questionnaires. According to its results, 94.8% of adolescents had a mobile phone with internet access and the mean age at which they had their first phone was 11 years. Half of them had internet access through a contract with an internet provider and at least one out of four had unlimited data. In addition, 31.6% spent more than 5 hours a day online throughout the week, a percentage that increased to 49.6% during weekends. Only 29.1% reported that parents had set up rules about their use of electronic devices, and 36.8% reported that their parents tended to use their phones during meals. The frequency of established rules and limits decreased by half by the second stage of the compulsory secondary education (ESO) cycle (around age 15-16 years).

Screen time in adolescents increased during and after the COVID pandemic, compared to prepandemic screen time. After the pandemic, there was a significant increase in screen time devoted to gaming and social media.10

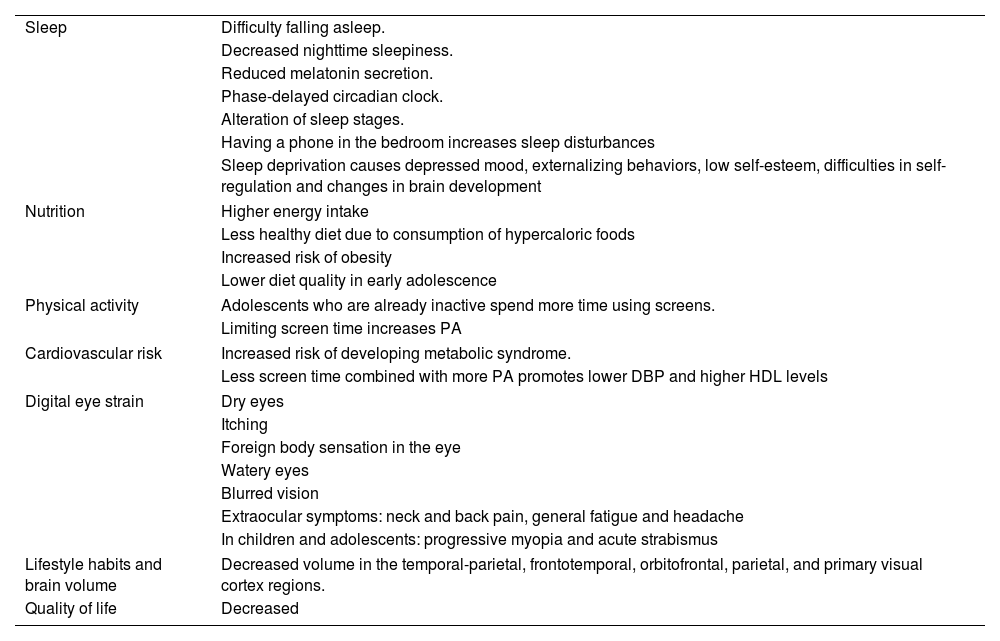

Impact of screen use on healthSleepMore screen time devoted to social media and gaming was associated with spending fewer hours in bed, going to bed later and longer sleep onset latency.10 In addition, use of screens before bedtime caused an increase in daytime somnolence, a decrease in nighttime somnolence, a decrease in melatonin secretion, a delay in the circadian rhythm and a decrease and delay in REM sleep. Adolescents who have screens in the bedroom are at increased risk of sleep-onset insomnia, maintenance insomnia and sleep disorders in general. However, turning off the devices at night decreased the risk compared to leaving the devices on or just silencing them. Streaming TV/videos, playing video games, listening to music, talking on the phone, texting, using social media or video chatting before bedtime were associated with difficulty falling and staying asleep.10 Insufficient sleep due to screen media use is associated with depressive symptoms, externalizing behaviors, low self-esteem, poor self-regulation and altered brain development.11

Diet and nutritionThere is moderately strong evidence that greater TV screen time is associated with increased energy intake and less healthy dietary habits,12 as TV watching may promote consumption of hypercaloric foods.13 The proportion of children with obesity is lower in those with screen times of less than 2 hours a day compared to those with screen times of 2 or more hours a day (4.3% vs 8.6%). Prospective and cross-sectional data have shown that screen time spent on television, gaming, texting or using social media is associated with lower dietary quality in early adolescence.14

Physical activityScientific evidence tends to corroborate that adolescents who are less physically active spend more time using screens.12 In addition, interventions aimed at reducing recreational screen media use have been found to achieve significant increases in leisure nonsedentary activity, supporting the displacement hypothesis according to which screen time replaces other, less sedentary forms of recreational activity.15

Body compositionThere is evidence that higher levels of screen time are associated with higher levels of adiposity,12 especially if screentime exceeds 2 hours.16 The mechanisms underlying this association are complex, but it appears that the impact of screentime on dietary habits plays a greater role than its impact on physical activity (PA).12

Cardiovascular riskPublished reviews have found evidence of a direct association between the time spent watching TV and the risk of developing metabolic syndrome.17 A systematic review found an association between screen exposure and the risk of developing high blood pressure.18 Combinations of low screen time and high step count were associated with a lower diastolic blood pressure and higher HDL cholesterol levels.19

Ocular involvementDigital eye strain (DES) is a condition manifesting with ocular and extraocular symptoms secondary to screen use.20 It is characterized by dry eyes, itching, foreign body sensation, watering, blurry vision and headache. The extraocular symptoms include stiffness and pain in the cervical and lumbar regions, general fatigue and headache. In children, the prevalence of DES increased between 50% and 60% during the pandemic. In childhood and adolescence, when the eye and vision are developing, DES is associated with progressive myopia and acute strabismus due to paradoxical accommodation. This type of strabismus manifests with blurry vision and headache,21 and requires urgent care to rule out a neurologic etiology.

Association with healthy lifestyle habitsReplacing 30 minutes of social media use, streaming or gaming by a healthier lifestyle habit was found to have an impact on BMI. Replacing 30 minutes of screen time by 30 minutes of physical activity in females and 30 minutes of sleep in males was associated with a lower follow-up BMI.22

Association between lifestyle habits and cerebral volumeLifestyle risk factors (decreased sleep duration, lower level of physical activity, greater BMI and greater screen time) were associated with decreased volume in different areas of the brain at the beginning of the study.22

Quality of lifeThere is moderately strong evidence of an association between screentime of 2 or more hours a day and a poorer perceived quality of life.12

Table 1 summarizes the evidence on the impact of digital media on physical health.

Impact of digital media on physical health.

| Sleep | Difficulty falling asleep. |

| Decreased nighttime sleepiness. | |

| Reduced melatonin secretion. | |

| Phase-delayed circadian clock. | |

| Alteration of sleep stages. | |

| Having a phone in the bedroom increases sleep disturbances | |

| Sleep deprivation causes depressed mood, externalizing behaviors, low self-esteem, difficulties in self-regulation and changes in brain development | |

| Nutrition | Higher energy intake |

| Less healthy diet due to consumption of hypercaloric foods | |

| Increased risk of obesity | |

| Lower diet quality in early adolescence | |

| Physical activity | Adolescents who are already inactive spend more time using screens. |

| Limiting screen time increases PA | |

| Cardiovascular risk | Increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome. |

| Less screen time combined with more PA promotes lower DBP and higher HDL levels | |

| Digital eye strain | Dry eyes |

| Itching | |

| Foreign body sensation in the eye | |

| Watery eyes | |

| Blurred vision | |

| Extraocular symptoms: neck and back pain, general fatigue and headache | |

| In children and adolescents: progressive myopia and acute strabismus | |

| Lifestyle habits and brain volume | Decreased volume in the temporal-parietal, frontotemporal, orbitofrontal, parietal, and primary visual cortex regions. |

| Quality of life | Decreased |

Abbreviations: DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; PA: physical activity.

In the neonatal period, the brain has more neurons than it will in later stages, but few synapses. From birth, neurons start to receive information through the senses and to form networks. Synapsis form to a large degree in the first two years of life and will determine neurologic functioning in adulthood. Based on the perceived stimuli, allowed by gene expression, synapses will develop differently. In addition, there are specific time windows for neurodevelopmental milestones. The stage from age 0 to 2 years is characterized by the development of gross and fine motor skills and language skills. Some of the stimuli that contribute to healthy neurodevelopment at this stage are unstructured play, manipulation of objects or contact with nature. When a child uses screens, the child is missing these necessary stimuli through the displacement of appropriate activities, so that screen time is an opportunity cost. On the other hand, the time adults spend using screens when raising their children also constitutes a missed opportunity for development through the loss of adult-child interaction.23

There is evidence that higher screen time in this age interval is associated with delayed language acquisition, a lower intellectual quotient and difficulties in focused attention during childhood.23 The same study found that higher screen time at age 2 years was associated with lower scores in communication, daily living skills and socialization at age 4 years. Outdoor play mitigated the association between higher screen time and poorer socialization and daily living skills outcomes.24

Background television viewing has a negative impact on language acquisition, cognitive development and the development of executive functions in children aged less than 5 years.24

At age 3 years, a screen time of 2 or more hours a day is associated with an increased probability of behavior problems, developmental delay and delayed vocabulary acquisition.25

Psychosocial developmentIn early childhood, psychosocial development is hindered by both screen use by the child and screen use by adults in the context of parent-child interaction. Babies need a sensible caregiver who is present and available. When babies use screens, they are unable to identify or express their needs. When it is the adult that is using a device, even if babies express their needs, adults may fail to respond adequately.

There is a strong association between parental screen time and children’s screen time in addition to disruptive behaviors in children to get the attention of parents. Using smart phones to reward or distract children aged 1 to 4 years can lead to children asking for the devices to soothe themselves and becoming upset when refused. The routine use of electronic devices to distract or soothe young children preclude self-soothing strategies and lead to overdependence on screens for emotion regulation and, at later stages, difficulties in self-regulation.23

AdolescenceNeurodevelopmentImportant developments take place during adolescence: (1) completion of the maturation of the limbic system and (2) progressive maturation of the cerebral cortex. Digital media interfere with development during adolescence in two ways: (1) increased activation of the limbic system through exposure to sources of immediate gratification and (2) decrease in frontal region activity through the displacement of age-appropriate stimuli.

Multitasking involving screens is associated with poorer cognitive outcomes, decreased ability to filter out distractions, increased impulsivity and decreased working memory. Adolescents that spend more than 4 hours a day using screens are more likely to experience severe cognitive difficulties.26

A study with a 2-year follow-up that used MRI evinced the causal relationship between screen use and brain development in relation to reading in early adolescence. Television viewing was associated with a reduction in the time spent reading, with an impact on the interpretation of verbal messages as well as the speed and quality of reading out loud.27

Psychosocial developmentSocial media may lead to exposure to misinformation and/or contradictory information at ages in which children lack sufficient cognitive skills or experience to interpret it critically, have a negative impact on peer group embeddedness or increase body image dissatisfaction.

A study conducted in the United States in a sample of 10 048 adolescents found a cross-sectional association between parental screen time and adolescent screen time. Parental mealtime and bedroom screen use were associated with increased and more problematic digital media use in adolescents. Parental monitoring and limit setting of screen use in adolescents was associated with less problematic digital media use in the cross-sectional analysis.28

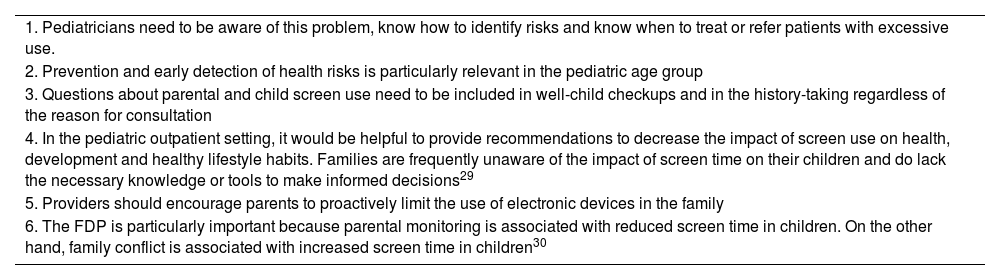

RecommendationsThe scientific evidence that has emerged in recent years demonstrates that screen use is a public health problem. Consequently, a variety of measures should be implemented, which are summarized in Tables 2–4.

Recommended measures to decrease the impact of digital media from the pediatric care setting.

| 1. Pediatricians need to be aware of this problem, know how to identify risks and know when to treat or refer patients with excessive use. |

| 2. Prevention and early detection of health risks is particularly relevant in the pediatric age group |

| 3. Questions about parental and child screen use need to be included in well-child checkups and in the history-taking regardless of the reason for consultation |

| 4. In the pediatric outpatient setting, it would be helpful to provide recommendations to decrease the impact of screen use on health, development and healthy lifestyle habits. Families are frequently unaware of the impact of screen time on their children and do lack the necessary knowledge or tools to make informed decisions29 |

| 5. Providers should encourage parents to proactively limit the use of electronic devices in the family |

| 6. The FDP is particularly important because parental monitoring is associated with reduced screen time in children. On the other hand, family conflict is associated with increased screen time in children30 |

FDP: Plan Digital Familiar®.

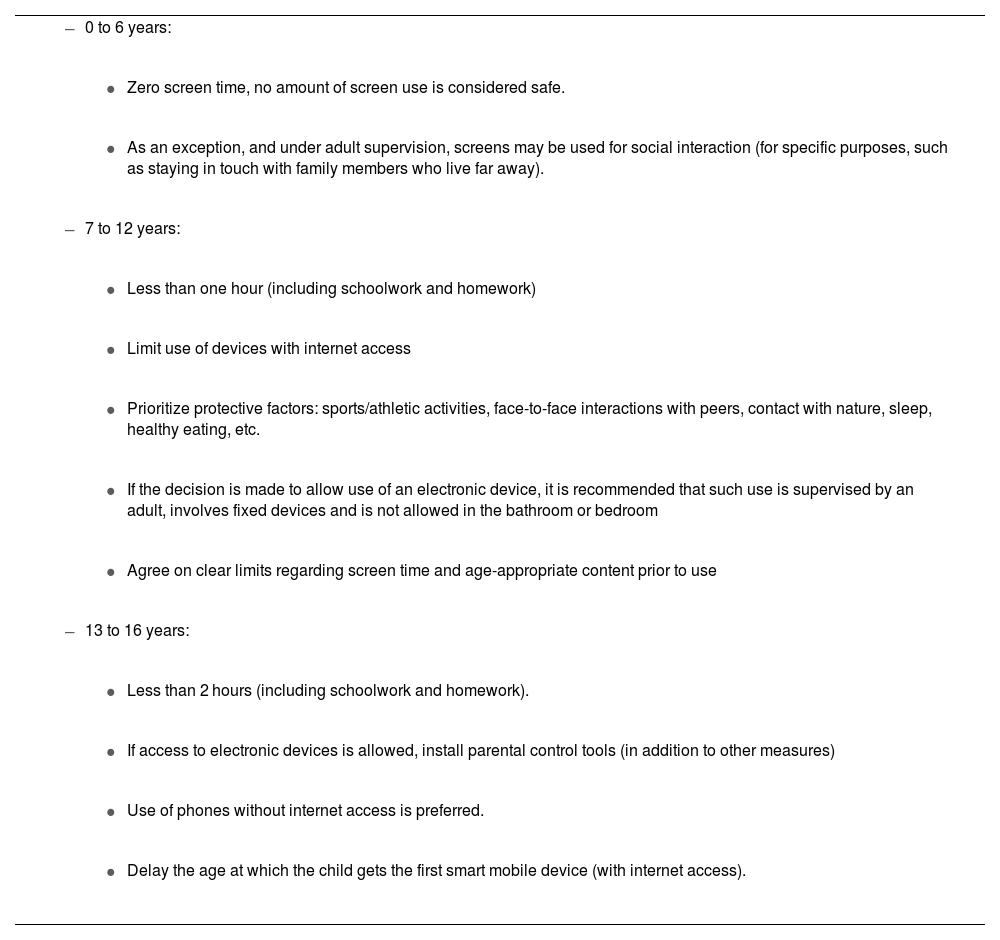

Screen use recommendations by age group.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

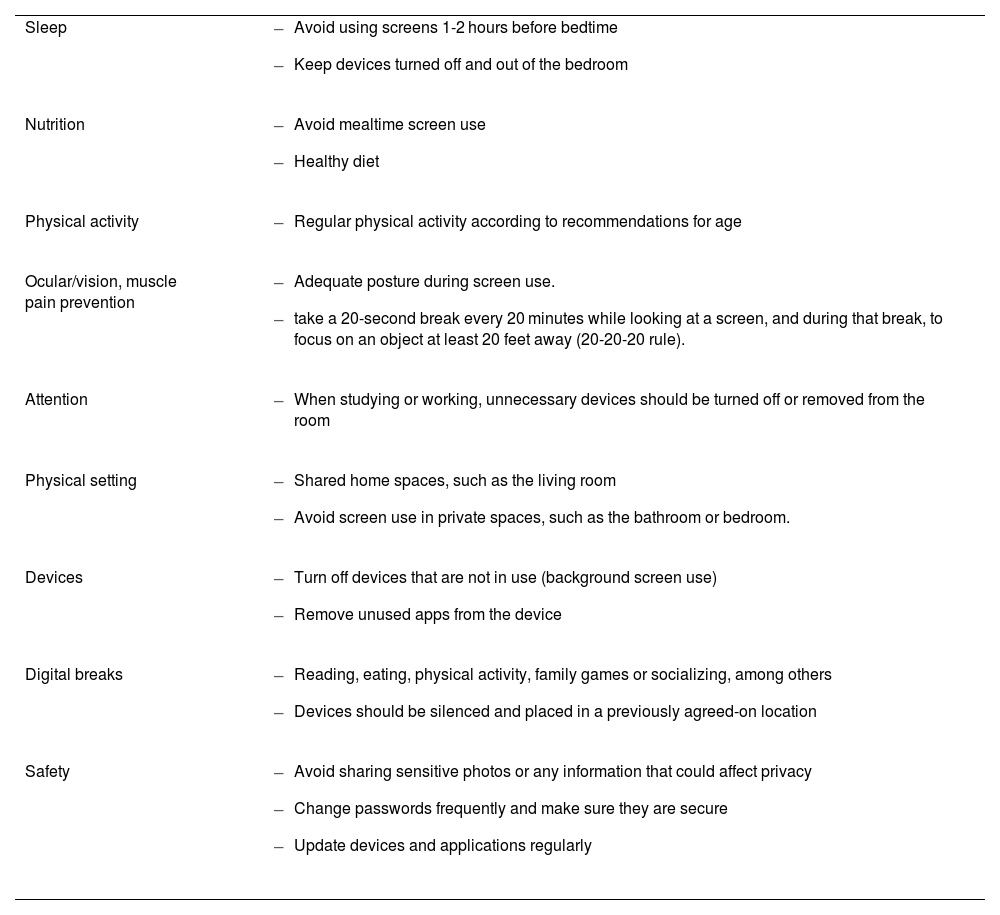

Screen use recommendations for families.

| Sleep |

|

| Nutrition |

|

| Physical activity |

|

| Ocular/vision, muscle pain prevention |

|

| Attention |

|

| Physical setting |

|

| Devices |

|

| Digital breaks |

|

| Safety |

|

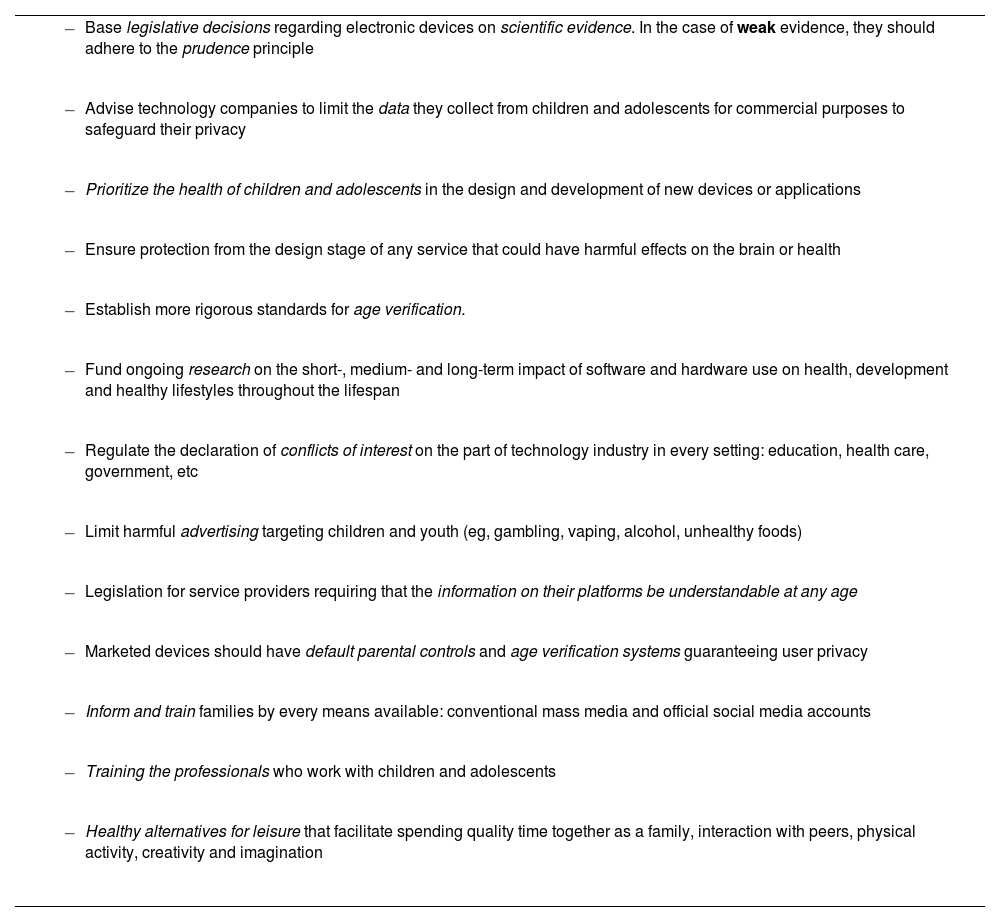

The role of the family in protecting children from the impact of screen exposure is significant. However, it would be irresponsible to place the full burden of protecting children on families. There are two key reasons for this: the time children spend in other settings, such as the school system, and the fact that some families, due to preexisting or unavoidable circumstances, are unable to fulfil this role. If governments continue to fail to implement the necessary measures, children and youth in vulnerable groups will suffer the most severe effects on health and development.30 Thus, it would be beneficial for both governments (Table 5) and education systems (Table 6) to implement measures.

Recommendations for governments about regulation and legislation.31,32

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

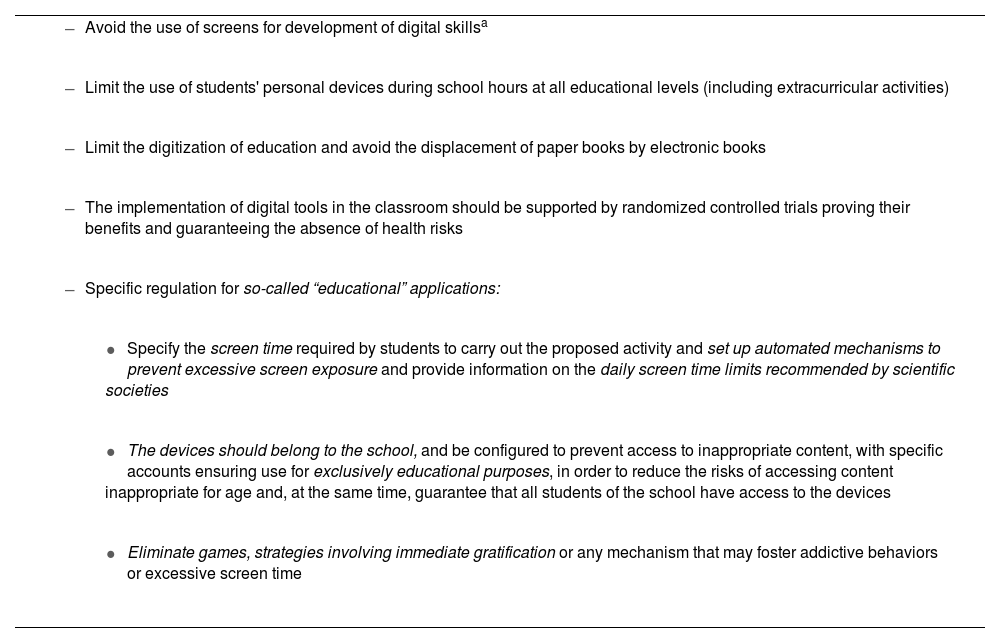

Recommendations for the education system.33,34

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As of today, education systems in most countries have been introducing digital media in education in the absence of sufficient scientific evidence corroborating beneficial effects in learning compared to approaches without their use or regarding their potential deleterious effects on health. Health research has provided evidence on the associated harms, but there is still no clear evidence regarding the potential benefits for learning.

From a public health perspective, it would be advisable for decisions in the education system to be based on scientific evidence, with studies demonstrating that the implementation of a given measure is beneficial in addition to short-, medium- and long-term surveillance of any potential adverse effects. Otherwise, education systems may be forced to make changes after implementation if evidence emerges of adverse effects on health and development.

ConclusionsIt is reasonable to say that there is sufficient evidence on the association between screen time and the displacement of healthy lifestyle habits in areas such as sleep, diet, physical activity, and face-to-face social interactions. Screen time also has an impact on cardiovascular risk, visual health, brain volume and quality of life. Its effects are greater in the pediatric age group, especially children aged less than 6 years and adolescents, as it interferes with normal neurologic and emotional development and reduces the capacity to self-regulate.

In early childhood, an increase in screen time was associated with language and psychomotor delays and lesser cognitive development. In adolescents, screen use was associated with an increased probability of cognitive difficulties, decreased attention, increased impulsivity, decreased peer group embeddedness and increased body image dissatisfaction. We found a strong association between parental screen time and children’s screen time, in addition to an association between parental screen time and behavioral changes in children

As the Committee on Health Promotion of the AEP, we consider several actions necessary: the revision of the recommendations given in the FDP (proposed revisions are featured in Tables 3 and 4), declaring screen use a public health problem, improving the training of pediatricians in its prevention and detection, improving research on the use of screens in education and health care systems, the establishment of legislation by governments to protect health and development, and advocating for the requirement of rigorous research to demonstrate, from the early stages of design and development, that technological products or services are safe for the health and brain of the population.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.