In this article, we describe the case of a female adolescent aged 13 years that visited the emergency department and had consumed duloxetine (600 mg) and extended-release morphine (300 mg) 17 h prior with suicidal intent. At home, she developed abdominal pain, vomiting, headache and somnolence and inability to urinate.

In the past year, the patient had experienced symptoms of an eating disorder, suicidal ideation and gender dysphoria, and had consumed alcohol and tobacco, and had received no medical or psychological care of any kind.

On arrival to hospital, her vital signs were in the normal range, and the salient findings of the physical examination were mild bradypsychia, pupillary miosis and discomfort on palpation of the hypogastric region. After 2 h in the emergency department, she exhibited obtundation, with a reduced response to physical stimuli, associated with bradypnea (8 breaths per minute) and shallow breathing, accompanied by a decrease in oxygen saturation (80%). Opioid-induced respiratory depression was suspected, leading to administration of supplemental oxygen and naloxone (0.01 mg/kg), which achieved immediate recovery of baseline mental status and resolution of the acute urinary retention. Four hours after the initial episode, the patient required naloxone again for management of respiratory depression.

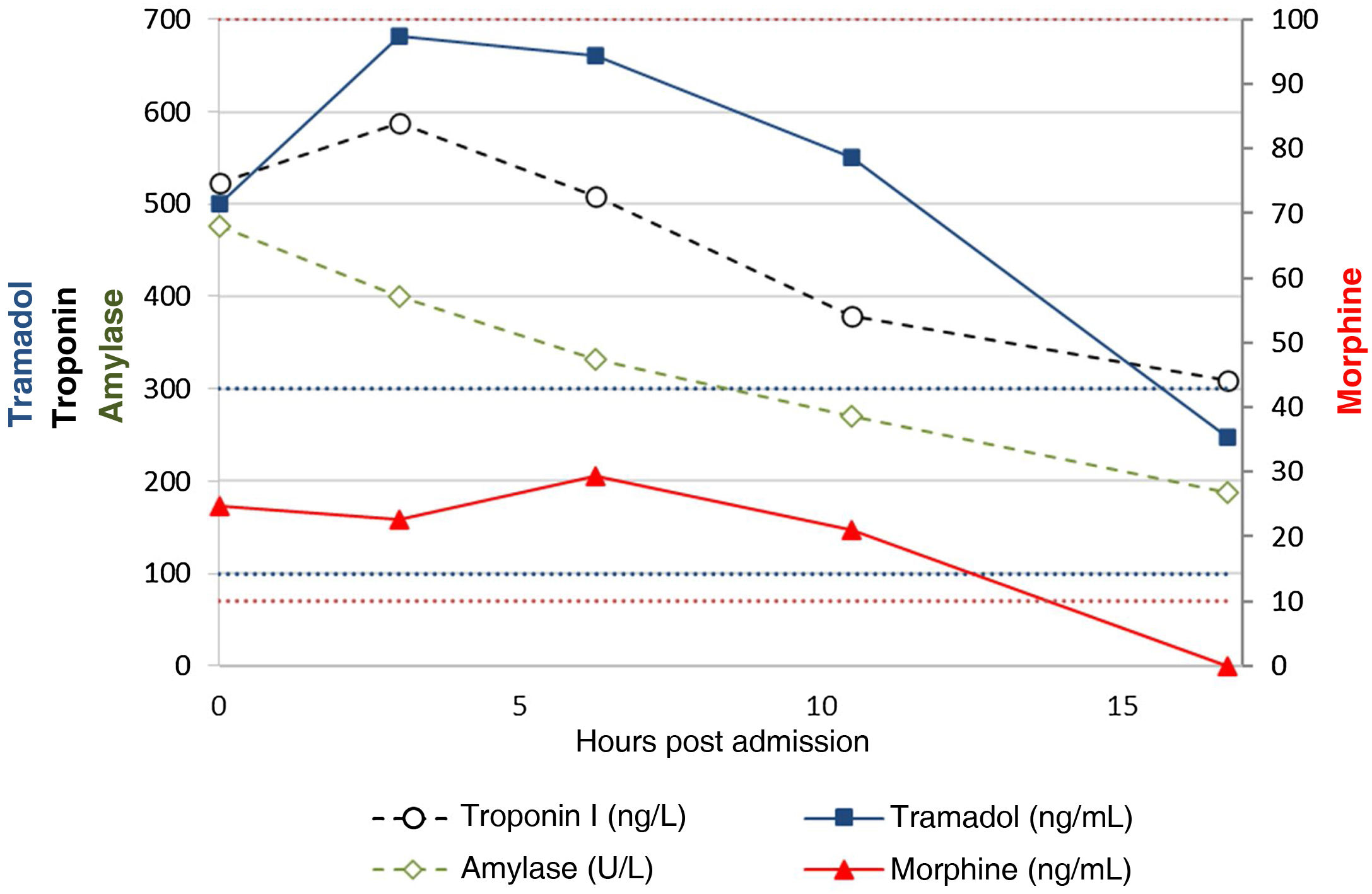

The baseline electrocardiogram and blood gas analysis were normal. The complete blood count and chemistry panel (18 h post-exposure) revealed leucocytosis (18 000 × 109 cells/L, 89.5% neutrophils), preserved renal and liver function, serum levels of glucose of 97 mg/dL, creatine kinase of 130 U/L and, most importantly, elevation of amylase (476 U/L; normal range, 25–101 U/L) and troponin I (593.3 ng/L [99th percentile]; normal range, <16 ng/L).

The level of paracetamol was below 2.5 μg/mL, and the basic urine drug test was positive for opiates, a finding confirmed in the expanded toxicological screen (blood and urine), with detection of morphine and tramadol through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. After this result, the patient acknowledged consumption of tramadol. Duloxetine was not detected (liquid chromatography- tandem mass spectrometry). During her stay, the patient underwent serial blood tests that exhibited progressive normalization of the abnormalities described above, and only the troponin I levels remained elevated until day 6, while all the electrocardiograms remained normal (Fig. 1).

The patient did not experience further clinical worsening and remained under observation in the emergency department for 24 h, after which she was admitted to the child and adolescent inpatient psychiatric unit, where she did not experience complications, and subsequently evaluated with an ultrasound examination in the paediatric cardiology department, the results of which were normal.

Tramadol is an opioid used for analgesia on account of the effects that result from the selective binding of its metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, to μ opioid receptors. In addition, it inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, which augments the potential adverse effects in the case of an overdose (opioid syndrome, serotonin syndrome and/or risk of seizures),1 and can be cardiotoxic at high doses.2 Tramadol poisoning is rare in paediatrics; in this patient, we found a peak level of 681 ng/mL (therapeutic range, 100−300 ng/mL),3 similar to the levels found in previous reports of paediatric poisoning in the literature.2 The half-life of tramadol in the patient was 8.8 h, higher than the one described following administration of therapeutic doses (6 h).1

Usually, opioid overdose causes respiratory depression, with a risk of severe hypoxaemia and cardiac arrest, although direct cardiotoxicity is not a common manifestation. Evidence from some animal models has shown an association of chronic consumption of tramadol with myocardial inflammatory illness, and a published paediatric case report described coronary disease due to vasospasm following fentanyl poisoning.4,5

Acute hypoxaemia results in an increase in cell membrane permeability due to ischaemic injury, and this in turn results in leakage of intracellular salivary or pancreatic amylase. Chronic hypoxaemia causes lactic acidosis. Both mechanisms can lead to hyperamylasaemia, and one such case has been described following tramadol poisoning.6 It is also important to remember that morphine and codeine can make the sphincter of Oddi spasm. Given the absence of manifestations of acute pancreatitis, we assume that the 2 episodes of respiratory depression were what caused hyperamylasaemia in this patient, with a persistently elevated level of 187 U/L 16 h after admission.

Serotonin syndrome is a potentially fatal condition caused by increased serotonergic activity in the nervous system. The symptoms include altered mental status, autonomic instability and neuromuscular hyperactivity and nonspecific abnormalities in laboratory tests. The ingestion of multiple drugs that block the reuptake of serotonin can cause this syndrome.

Opioid poisoning should be suspected in paediatric patients with troponin elevation and no electrocardiographic evidence of cardiac arrest or ischaemia and no signs of pancreatitis. The complex synergy of tramadol and morphine poisoning justified the anomalous laboratory findings in this case.